Relevance of Culture and Values for Community/Public Health Nursing

Linda Haddad and Claudia M. Smith∗

Focus Questions

What are culture, race, and ethnicity?

What is the relation of culture to health and health behaviors?

How do values influence attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors related to health and illness?

What are health disparities and disparities in health care?

What is cultural and linguistic competence?

Why should community/public health nurses be concerned with being culturally competent?

What core categories should community/public health nurses explore when assessing culture?

Key Terms

Asylees

Cultural and linguistic competence

Cultural assessment

Cultural competence

Cultural pluralism

Cultural self-assessment

Culture

Culture-bound syndromes

Discrimination

Ethnicity

Ethnocentric

Health care disparities

Health disparities

Health literacy skill

Immigrants

Race

Racism

Refugees

Rite

Ritual

Stereotyping

Subcultures

Values

Cultural pluralism in the united states

Cultural pluralism can be defined as mutual appreciation and understanding of the various cultures and subcultures in a society. It means that there exist cooperation between and among members of different groups and harmony in the presence of diverse lifestyles, communication patterns, religious traditions, family structures, expressions of care, and health-related beliefs and practices. With a population that exceeds 310 million, the United States is a nation of rich cultural pluralism. More than 110 million people, or one in three individuals, self-identify with one or more of the federally recognized racial and/or ethnic minority groups described in Box 10-1. The term cultural pluralism can refer to a wide variety of characteristics, including religion, gender, sexual orientation, age, and related factors. The federal census data provide an overview of the types of racial and ethnic diversity found in contemporary U.S. society. Much of the community/public health nurse’s practice is interconnected with population demographics, especially characteristics related to racial and ethnic trends and the socioeconomic backgrounds of individuals, families, groups, and communities.

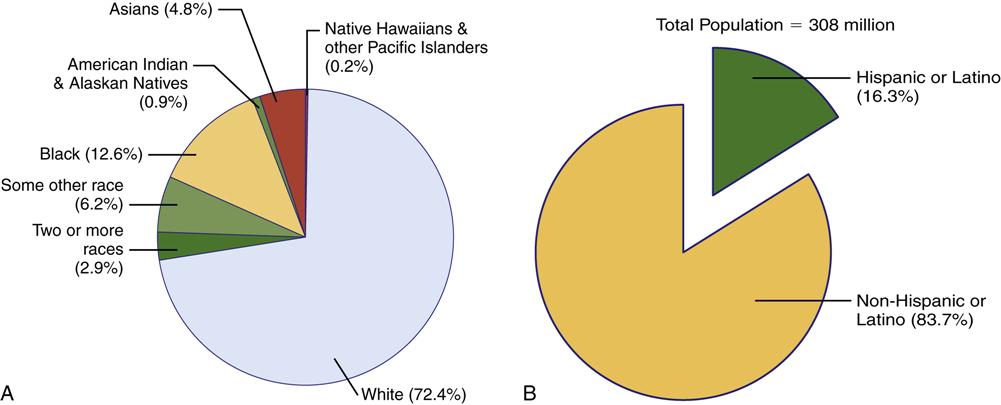

Figure 10-1 summarizes the current U.S. population by racial and ethnic categories. The country’s 197 million non-Hispanic whites comprise 63.7% of the total population (Humes, Jones, & Ramirez, 2011). In discussing the growth among racial and ethnic minority populations, former Census Bureau Director Louis Kincannon reported that there are more people from minority groups in this country today than the total U.S. population in 1910. To put this into a broader context, the U.S. minority population is larger than the total population of all but 11 countries in the world (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2010a).

Hispanics comprise the largest ethnic minority group, with 50 million people, or 16.3% of the total population (Humes, Jones, & Ramirez, 2011). The Hispanic population grew by over 40% during the period between 2000 and 2010. California (37.6%) and Texas (37.6%) have the largest Hispanic population of any states, followed by Florida. Blacks comprise the largest racial minority group, with 39 million, or 12.6% of the total population. The black population increased by 12% between 2000 and 2010. Texas has the largest population of blacks of any state (3.1 million) followed by New York (3 million) (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2010a).

The other federally defined racial minority groups are Asians (14.6 million, or 4.8% of the total population), with the largest numbers found in New York and Texas (Humes, Jones, & Ramirez, 2011; U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2010a). The Asian population also grew by over 40% between 2000 and 2010. Many of the American Indians/Alaska Natives (3 million, or 0.9% of the total population) reside in California, Oklahoma, Arizona, Texas, Florida, and Alaska. Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders (540,000, or 0.2% of the total population) are found primarily in Hawaii, California, and Washington. In the 2010 census, almost 35% of respondents reported that they belonged to two or more races. By the year 2030, Hispanics will represent 19% of the population, and Asians are expected to increase to 7% (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2007).

Greater diversity in the population means that community/public health nurses are likely to come into frequent contact with members of different cultures and subcultures. The nurse’s health-related cultural beliefs and values may vary significantly from those of individuals, groups, and communities different from his or her own. Bridging the racial, ethnic, and cultural divides in health poses a challenge for all nurses, especially for community/public health nurses, who provide care to diverse groups of individuals and families in community settings. Cultural and linguistic competence is a requisite skill for all nurses to provide culturally congruent, appropriate, and meaningful nursing and health care; avoid unnecessary misunderstandings and miscommunication; and ensure that the public receives the highest quality of community/public nursing care.

Culture: what it is

There are more than 1.8 million websites containing definitions of culture. However, most anthropologists agree that culture is dynamic and refers to a group of people who have the following characteristics:

• A shared pattern of communication

• Similarities in dietary preferences and food preparation

• Predictable socialization patterns

According to the nurse–anthropologist Madeleine M. Leininger, who established the specialty called transcultural nursing, the term culture refers to the learned and shared beliefs, values, and life ways of a group that are generally transmitted from one generation to the next and influence people’s thoughts and actions. An integral part of daily living, culture has many hidden and built-in directives and rules of behavior, beliefs, rituals, and moral–ethical decisions that give meaning and purpose to life (Leininger & McFarland, 2006). Community/public health nurses’ knowledge of culture and skill in conducting comprehensive cultural assessments guide them in providing culturally competent care to people from diverse cultures.

It should be noted that there are nonethnic cultures such as those based on occupation or profession (e.g., culture of nursing, medicine, or the military); socioeconomic background (e.g., culture of poverty or culture of affluence); sexual orientation (gay, lesbian, or transgendered cultures); age (e.g., adolescent culture or culture of older adults); and ability/disability (e.g., culture of the deaf/hearing impaired or culture of the blind/visually impaired). Shared life experiences (e.g., homelessness or surviving a war) are another basis for nonethnic cultures.

For community/public health nurses who provide care for diverse populations, an understanding of the concept of culture and its importance in health care is paramount. Symbols, gestures, and behaviors are often misunderstood because they have different meanings for the nurse and the client. Failure to effectively communicate cross-culturally may lead to serious misunderstandings, frustration, and/or conflict between clients and nurses. For example, an Afghani family anxiously awaits the results of the mother’s clinical tests. When the nurse comes out to greet the family with the results of the tests, she smiles broadly and gives the American “thumbs up” gesture. The family, horrified, rushes out of the office in distress. In the U.S. culture, the “thumbs up” gesture indicates that everything is fine, but in many Middle Eastern cultures, this same gesture is considered a vulgar sign.

Culture affects the manner in which people determine who is healthy or sick; what causes health or illness; what healer(s) and intervention(s) are used to prevent and treat diseases and illnesses; how long a person has an illness; what is appropriate role behavior in sickness; and when a person is believed to have recovered from an illness. Culture also influences the way people receive health care information, exercise their rights and protections, and express their symptoms and health-related concerns. In some instances, biomedicine can conflict with cultural beliefs concerning health and illness. For example, although an estimated 30% of the world population has tuberculosis (TB), in many parts of Mexico and Asia, the persistent cough and night sweats associated with the disease are so prevalent that these symptoms are considered normal. Because people fail to recognize that they have a disease, they do not seek treatment. Thus, cultural beliefs can adversely affect large populations because infected individuals unknowingly transmit the TB bacillus to others.

Subcultures

Subcultures are groups of individuals who, although members of a larger cultural group, have shared characteristics that are not common to all the members of the larger culture. The subculture is a distinguishable group. Such groups and cultural differences within the groups may be based on geography (north or south, urban or rural), economic status (poor or affluent), ethnicity, and other factors. For example, persons living in Appalachia are a subcultural group based on geographical location. Differences can also be found within an identifiable subculture. For example, Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and Central and South Americans are all Hispanics, yet all these groups have distinct subcultural patterns that distinguish them from one another. For this reason, the federal pan-ethnic categories used in gathering census data and reporting health disparities are sometimes criticized for failing to recognize significant intragroup differences.

Persons acting in a particular social capacity or group can also be considered a subculture. These groups develop their own standards of behavior, goals, and values. The nursing profession and the health care system are examples of cultures or subcultures that have their own standards and beliefs, including the following (Ludwig-Beymer, 2007; Spector, 2004):

• Standardized definitions of health and illness and the importance of technology

• Health care practices (immunizations, annual physical examinations, and Papanicolaou [Pap] tests)

• Likes (promptness, neatness and organization, and adherence)

• Dislikes (tardiness, disobedience, and disorganization)

Differences between Health Care Provider’s and Client’s Culture or Subculture

Differences between the client’s and the provider’s cultures or subcultures become apparent when the client has traditional perceptions, beliefs, and practices that differ from the nurse’s practices. The community/public health nurse must be sensitive to differences among individuals that may result in practices such as coming to the clinic at unscheduled times, inability to describe symptoms accurately, failure to follow treatment plans, and lack of confidence in the medical system. A client’s mistrust and lack of confidence in the health care system influence the client’s acceptance of, and participation in, the health care planning process. Although nurses may view these behaviors as noncompliant, these behaviors may have a cultural basis. In one study, 51% of physicians surveyed in Los Angeles indicated that their clients do not adhere to treatment because of cultural and language barriers (Youdelman & Perkins, 2002). Some African Americans are likely to mistrust the health care system because of the Tuskegee experiments, in which 400 African American men were denied treatment for syphilis from 1932 to 1972 as part of a government study tracking the path of the disease from onset to autopsy (Bloche, 2001). Other studies reported that fewer than one half of Hispanics and Asian Americans felt confident of their ability to get the needed health care (Collins et al., 2002).

Values

Values are preferences (or ideals) that give direction to human life by influencing beliefs and behaviors. Culture, family, personality, and life experiences contribute to the formation of values. Values make us who we are and are important in nursing because they have the potential to create barriers or facilitate communication and relationships between nurses and clients. When people interact, as nurses and clients do, their values interact. Values influence human behavior, including behavior related to health and illness; they are the foundation for acceptance and participation or rejection and repudiation of health care planning and health care (Andrews & Boyle, 2008).

Differences in values and customs can be found among cultures. The culture and the society in which the individual lives or with which he or she identifies strongly influence that person’s values. Although members of a particular culture tend to share many ideas and values, differences in values exist within that culture as well. Any assumption on the part of health care providers that a given idea or custom is shared by all members of a culture can be dangerously misleading.

The most prominent values in the United States are reflective of the dominant white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant (WASP) cultural group. Individualism and mastery over nature are American values that permeate many aspects of health care. Privacy rights and personal freedom are based on the value of individualism. Individuals are responsible for seeking health care and cooperating with health care providers and for promoting their own health and preventing illness. Medicine attempts to control disease and distress, which is represented in such aggressive terms as conquering cancer and fighting tuberculosis. Scientific knowledge, sophisticated technologies, and a belief in intervention and mastery over problems, not a fatalistic submission to illness, are evident in health care practice. Other significant and dominant U.S. values include materialism (importance of possessions and money), reliance on technology, orientation to instant time and action, emphasis on youth, and less respect for authority and older adults.

In some of the cultures and subcultures in the United States, however, individualism is not a primary value. Belonging to family and community is more important. Personal privacy may not be that important; rather, sharing of information and family or group participation in the decision-making process may be of greater value. Health may or may not be a primary value. Acceptance of health conditions, rather than seeking interventions aimed at curing or fixing the problems, may be more important. The meaning of illness and differences in client–provider cultural and subcultural values may become evident during client–provider interactions.

Had the nurse been aware of the value placed by the gypsy (Roma) group on providing support to members in crisis, the nurse might have anticipated a large gathering and preplanned accordingly. In such a situation, the nurse might acknowledge the family’s need for closeness and negotiate a reasonable limit on the number of people in attendance. The nurse might identify suitable accommodations for the remainder, for example, alternate family members between the hospital room and the cafeteria.

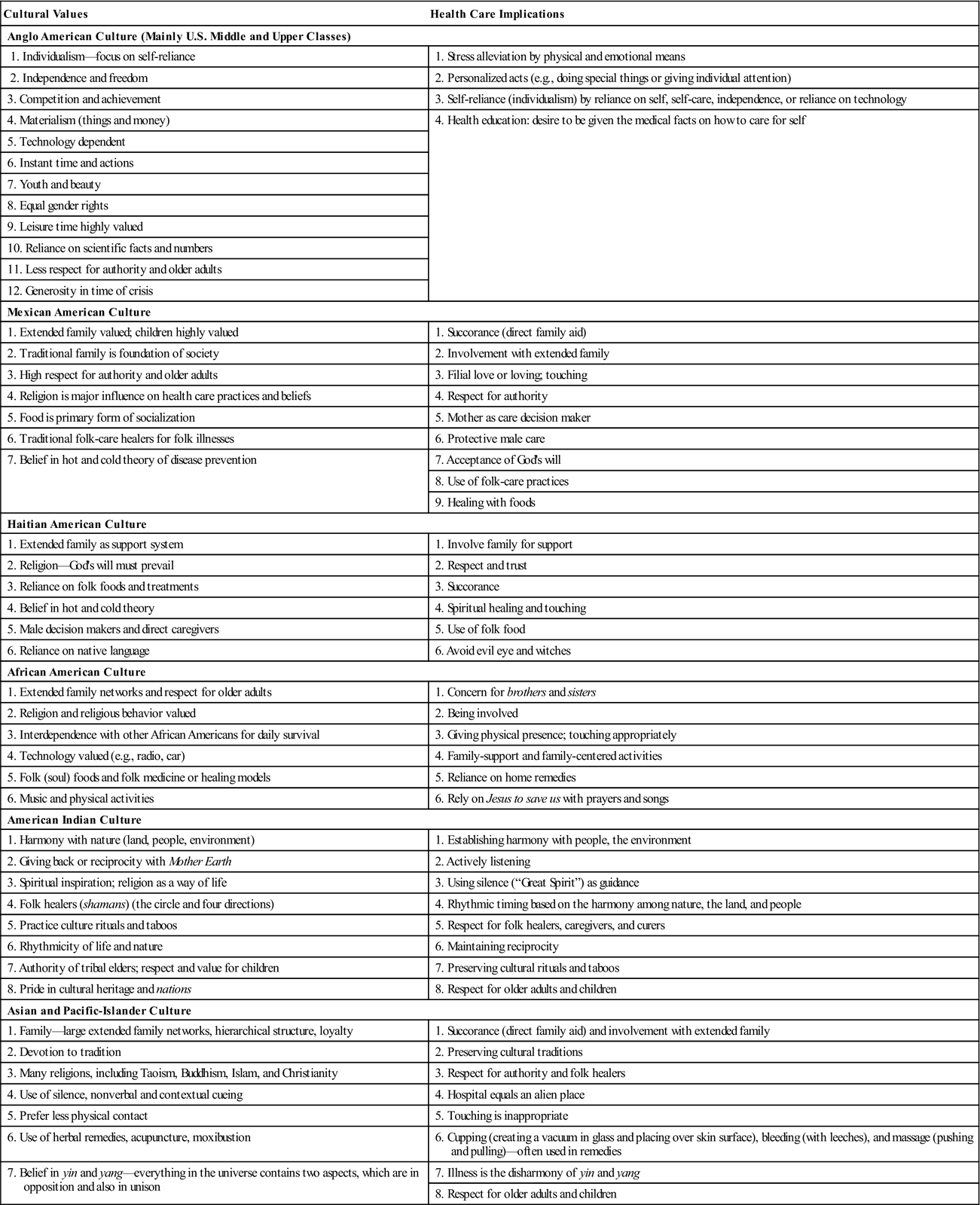

Table 10-1 provides a sample list of cultural values for select cultures and identifies some implications for nurses providing health care to these populations.

Table 10-1

Cultural Values for Select Groups—Implications for Community/Public Health Nurses

| Cultural Values | Health Care Implications |

| Anglo American Culture (Mainly U.S. Middle and Upper Classes) | |

| 1. Individualism—focus on self-reliance | 1. Stress alleviation by physical and emotional means |

| 2. Independence and freedom | 2. Personalized acts (e.g., doing special things or giving individual attention) |

| 3. Competition and achievement | 3. Self-reliance (individualism) by reliance on self, self-care, independence, or reliance on technology |

| 4. Materialism (things and money) | 4. Health education: desire to be given the medical facts on how to care for self |

| 5. Technology dependent | |

| 6. Instant time and actions | |

| 7. Youth and beauty | |

| 8. Equal gender rights | |

| 9. Leisure time highly valued | |

| 10. Reliance on scientific facts and numbers | |

| 11. Less respect for authority and older adults | |

| 12. Generosity in time of crisis | |

| Mexican American Culture | |

| 1. Extended family valued; children highly valued | 1. Succorance (direct family aid) |

| 2. Traditional family is foundation of society | 2. Involvement with extended family |

| 3. High respect for authority and older adults | 3. Filial love or loving; touching |

| 4. Religion is major influence on health care practices and beliefs | 4. Respect for authority |

| 5. Food is primary form of socialization | 5. Mother as care decision maker |

| 6. Traditional folk-care healers for folk illnesses | 6. Protective male care |

| 7. Belief in hot and cold theory of disease prevention | 7. Acceptance of God’s will |

| 8. Use of folk-care practices | |

| 9. Healing with foods | |

| Haitian American Culture | |

| 1. Extended family as support system | 1. Involve family for support |

| 2. Religion—God’s will must prevail | 2. Respect and trust |

| 3. Reliance on folk foods and treatments | 3. Succorance |

| 4. Belief in hot and cold theory | 4. Spiritual healing and touching |

| 5. Male decision makers and direct caregivers | 5. Use of folk food |

| 6. Reliance on native language | 6. Avoid evil eye and witches |

| African American Culture | |

| 1. Extended family networks and respect for older adults | 1. Concern for brothers and sisters |

| 2. Religion and religious behavior valued | 2. Being involved |

| 3. Interdependence with other African Americans for daily survival | 3. Giving physical presence; touching appropriately |

| 4. Technology valued (e.g., radio, car) | 4. Family-support and family-centered activities |

| 5. Folk (soul) foods and folk medicine or healing models | 5. Reliance on home remedies |

| 6. Music and physical activities | 6. Rely on Jesus to save us with prayers and songs |

| American Indian Culture | |

| 1. Harmony with nature (land, people, environment) | 1. Establishing harmony with people, the environment |

| 2. Giving back or reciprocity with Mother Earth | 2. Actively listening |

| 3. Spiritual inspiration; religion as a way of life | 3. Using silence (“Great Spirit”) as guidance |

| 4. Folk healers (shamans) (the circle and four directions) | 4. Rhythmic timing based on the harmony among nature, the land, and people |

| 5. Practice culture rituals and taboos | 5. Respect for folk healers, caregivers, and curers |

| 6. Rhythmicity of life and nature | 6. Maintaining reciprocity |

| 7. Authority of tribal elders; respect and value for children | 7. Preserving cultural rituals and taboos |

| 8. Pride in cultural heritage and nations | 8. Respect for older adults and children |

| Asian and Pacific-Islander Culture | |

| 1. Family—large extended family networks, hierarchical structure, loyalty | 1. Succorance (direct family aid) and involvement with extended family |

| 2. Devotion to tradition | 2. Preserving cultural traditions |

| 3. Many religions, including Taoism, Buddhism, Islam, and Christianity | 3. Respect for authority and folk healers |

| 4. Use of silence, nonverbal and contextual cueing | 4. Hospital equals an alien place |

| 5. Prefer less physical contact | 5. Touching is inappropriate |

| 6. Use of herbal remedies, acupuncture, moxibustion | 6. Cupping (creating a vacuum in glass and placing over skin surface), bleeding (with leeches), and massage (pushing and pulling)—often used in remedies |

| 7. Belief in yin and yang—everything in the universe contains two aspects, which are in opposition and also in unison | 7. Illness is the disharmony of yin and yang |

| 8. Respect for older adults and children | |

Data compiled from Andrews, M., & Boyle, J. (2003). Transcultural concepts in nursing care (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; Lipson, J., Dibble, S., & Minarik, P. (1996). Culture and nursing care: A pocket guide. San Francisco: University of California, San Francisco Press; Purnell, L., & Paulanka, B. (2003). Transcultural health care—A culturally competent approach. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis; and Spector, R. E. (2004). Cultural Diversity in health and illness (6th ed.). CT: Appleton-Lange.

Race

The concept of race is separate from the concept of ethnicity, although the terms are often used interchangeably. Race has traditionally referred to a group of individuals who share common biological features. Nonetheless, race as a valid biological concept is being challenged, and many people have called for abandoning the concept of race altogether (Fullilove, 1998; Osborne & Feit, 1992). The Human Genome Project, an extensive worldwide gene-mapping project, has determined that although clear differences in appearance are sometimes evident, no genetic differences exist among races. In other words, the minute differences among gene types are as much the result of differences among members of the same race (white versus white, black versus black) as of differences between races (white versus black versus Asian).

Despite the scientific evidence, racial and ethnic distinctions are reflected in the formal reporting and presenting of federal health and vital statistics data. Although both terms are important determinants in collecting data and presenting health statistics, the concept of race as used by the U.S. Census Bureau reflects self-identification by people indicating the race or races with which they feel most closely related, and this classification includes both racial and national-origin groups. The racial classifications that the U.S. Census Bureau uses adhere to the October 30, 1997, Federal Register notice entitled Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity, issued by the Office of Management and Budget. These classifications are presented in Box 10-1.

Ethnicity

Ethnicity refers to a “shared culture and way of life, especially as reflected in language, folkways, religious and other institutional forms, material culture such as clothing and food, and cultural products such as music, literature and art” (Smedley et al., 2003, p. 523). Ethnicity provides a sense of social belonging and loyalty, and each of us belongs to an ethnic group of one kind or another. One of the most important characteristics of ethnicity is that it provides a sense of belonging or identity.

As noted earlier, ethnicity is commonly used interchangeably with race, although differences between the terms do exist. Federal documents and reports delineate data by four major racial groups: (1) American Indian, including Alaska Natives, Eskimos, and Aleuts; (2) Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders; (3) blacks; and (4) whites; and by one ethnic group, Hispanics, under the combined term racial and ethnic groups. Hispanics create a conundrum for census takers because they are considered to belong to either of two racial groups. Some Hispanics are considered black and some white. Data are sometimes collected by ethnic distinction alone—Hispanic and non-Hispanic—in which case, most people of various races fall into the non-Hispanic category. Data are sometimes collected by race and ethnic groups. When this distinction is made, Hispanics are listed as an ethnic group, and members of black and white racial groups who are not Hispanic are listed as black non-Hispanic or white non-Hispanic. Collecting data by racial and ethnic categories is considered important in health care because certain groups tend to be more resistant or vulnerable to specific health problems. The collection and value of such data for health care professionals will diminish as groups intermarry and their progeny become increasingly multiracial.

Because the terms race and ethnicity are often used interchangeably, community/public health nurses must understand the distinctions between the terms. Nurses should avoid labeling clients by using skin markers or other features as identifiers and classifying individuals on the basis of group association. In some instances, knowing the client’s race or ethnic type is helpful in identifying individuals and groups at increased risk for certain diseases, recognizing normal and abnormal biocultural variations in the physical assessment, and evaluating clients’ responses to certain medications. The most appropriate way to determine the client’s racial or ethnic identity is to ask, “How do you identify yourself?”

Racial and ethnic health and health care disparities

Disparities in health and health care exist across the spectrum of racial and ethnic groups and involve a range of health concerns (Box 10-2). Health disparities are differences or inequalities in health status, including differences in life expectancy, mortality, and morbidity. Healthy People 2020 states that health disparities are “a particular type of health difference that is closely linked with social, economic, and/or environmental disadvantage. Health disparities adversely affect groups of people who have systematically experienced greater obstacles to health based on their racial or ethnic group; religion; socioeconomic status; gender; age; mental health; cognitive, sensory, or physical disability; sexual orientation or gender identity; geographic location; or other characteristics historically linked to discrimination or exclusion” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2010).

Although significant progress has been made in improving life expectancy and overall indicators of health, health disparities have persisted. The objectives set forth in Healthy People 2020 (USDHHS, 2010) were designed to increase quality and years of healthy life and eliminate health disparities for each of the ethnic minority groups. Although significant progress has been made in reducing some health disparities, there is compelling evidence that race and ethnicity correlate with persistent and often increasing health disparities among multiple racial and ethnic minority groups at all stages of life.

Life expectancy rates are often considered reflections of the overall health of a population. Since the beginning of the twentieth century, life expectancy at birth has increased from less than 50 years to more than 77.8 years. Life expectancy at birth increased gradually for whites and blacks of both genders from 2000 through 2009. During this period, life expectancy increased the most for black males (2.7 years) and black females (2.3 years) but also for white males (1.5 years) and white females (1 year). Life expectancy reached a record high for whites of both genders in 2009; for blacks of both genders, it remained unchanged from 2008 to 2009 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010). Although current life expectancy data for Hispanics and American Indians/Alaska Natives are not available, the higher incidence of diabetes and liver disease in these populations increases the likelihood that they will live fewer years (Indian Health Service, 2012; Office of Minority Health, 2007a, 2007b).

Most racial and ethnic minority groups have higher infant mortality rates; higher rates of death from cancer, heart disease, diabetes, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS); more chronic and disabling diseases; and lower immunizations rates. For example, African American, American Indian, and Puerto Rican infants have markedly higher death rates compared with white infants. For the past two decades, there has been a widening disparity between African American and white infant death rates. African American women are more than twice as likely to die of cervical cancer compared with white women and more likely to die of breast cancer compared with women of any other racial or ethnic group. Although heart disease and stroke are the leading causes of death among all racial and ethnic groups, death rates for heart disease are 20% higher and death rates for strokes are 40% higher among African American adults than among white adults. American Indians and Alaska Natives are 2.6 times more likely to have diabetes, with the incidence of non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus being as high as 60% in some Indian nations. Compared with their white counterparts, African Americans are 2 times and Hispanics 2.9 times more likely to have been diagnosed with diabetes (CDC, 2006; Indian Health Service, 2012; Office of Minority Health, 2007b; Smedley et al., 2003; USDHHS, 2001a).

Some minority populations experience problems with access to and quality of health care services. Research indicates that some minority individuals, groups, and communities receive a lower quality of health care than do nonminority ones, even when insurance status, income, age, and severity of conditions are equal (CDC, 2006; Office of Minority Health, 2007a, 2007b; Smedley et al., 2003).

Health care disparities (emphasis added) may be defined as “racial or ethnic difference in the quality of health care that are not due to access related factors or clinical needs, preferences, and appropriateness of intervention” (Smedley et al., 2003, pp. 3-4).

The occurrence of many illness and other health problems is disproportionally higher in some racial and ethnic groups in the United States; access to health care may be more restricted. In populations with equal access to health care, disparities exist because of the operation of the health care system and discrimination, biases, stereotyping, and uncertainty of the clinicians (Smedley et al., 2003). For example, African Americans have the highest incidence of end-stage renal disease but are less likely to receive renal dialysis, be referred for transplantation, or receive a kidney transplant. Hispanic and African Americans are less likely to receive evidence-based mental health care in accordance with professional treatment guidelines, and more than one fourth of Asian Americans report experiencing difficulty in accessing specialists (CDC, 2006; Office of Minority Health, 2007b; Smedley et al., 2003; USDHHS, 2001b).

Even when conditions are comparable (e.g., comparable insurance status, educational level, income level, access to health care professionals), minority members are less likely than whites to receive appropriate treatment or surgical procedures. African Americans are more likely to be diagnosed as psychotic but are less likely to be given antipsychotic medicines and more likely to be hospitalized involuntarily, to be regarded as potentially violent, and to be placed in restraints (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2005; CDC, 2006; George, 2000; Office of Minority Health, 2007b; Polyakova & Pacquiao, 2006; Smedley et al., 2003).

A wide array of factors contributes to health disparities. Patterns of segregation and discrimination, the health care environment, and specific individual health behaviors and beliefs play a role in the problem. A complex and fragmented health care environment makes receiving continuity of care difficult for people. Managed care and Medicaid managed care plans often disrupt community-based care and displace providers who are familiar with the culture and values of an ethnic community. Language barriers contribute to the problem, especially when care providers are unfamiliar with the language spoken by their clients. Geographically distant clinics and hospitals pose access problems, especially for economically stressed families without transportation. Some American Indians are required to travel more than 90 miles one way to obtain care at Indian Health Service facilities, and the wait ranges from 2 to 6 months for appointments in certain specialties such as obstetrics/gynecology and outpatient mental health (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2005; Government Accountability Office, 2005; Indian Health Service, 2007).

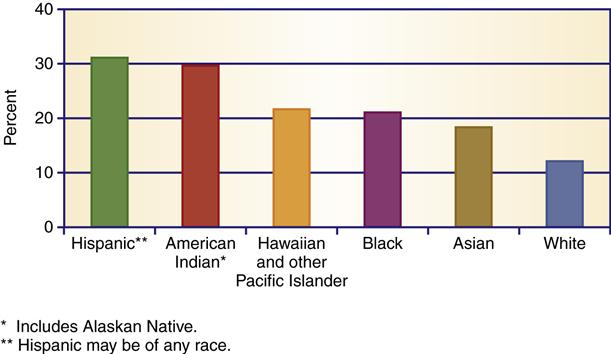

Role of insurance in health disparities

With 17.6% of the national gross domestic product (GDP) allocated to health care in 2009, the United States leads the world in health care spending (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, 2011). And yet, nations spending substantially less sometimes have healthier populations than the U.S. population. The U.S. performance is adversely affected by deep inequalities linked to income and health insurance coverage. The United States is the only Western industrialized nation without a universal health insurance system. Instead, the United States relies on employer-based private insurance and public coverage that fail to reach all citizens, with minority populations being at higher risk than whites for being underinsured or uninsured (see Chapter 21). Although more than one half of the U.S. population has health insurance coverage through their employers and nearly all older adults are covered through Medicare, more than 1 in 6 Americans who are not older adults (49.9 million) lack health insurance (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011a) (Figure 10-2). Lack of health insurance among vulnerable populations contributes to poorer access to health care and ultimately to health disparities. Hispanic Americans are almost three times more likely to be uninsured compared with whites (31% versus 12%), whereas 21% of African Americans are without health insurance. The cost of treatment is a major barrier to health care access in the United States.

More than 40% of the uninsured have no regular health care facility to go to when they are sick, and more than one third of the uninsured report that they or someone in their family went without needed care or prescription medicines because of cost (Government Accountability Office, 2005; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010; Rowland & Hoffman, 2005; U.S. Census Bureau, 2011a).

Strategies for eliminating health disparities

Eliminating health disparities is one of four major goals of the Healthy People 2020 objectives (USDHHS, 2010). The objectives are especially focused on eliminating health disparities by 2020 in key areas that cut across different racial and ethnic groups:

Federal and state governments, as well as nongovernmental health organizations, are committed to reducing health disparities in the U.S. population (USDHHS, Office of Minority Health, 2010b). Website Resource 10A ![]() provides a detailed list of recommended strategies to reach this goal. Community/public health nurses need to be aware of health disparities among and within racial and ethnic groups. All nurses should be aware of barriers to achieving optimal health and methods to facilitate attaining culturally competent health care for everyone. Recognizing cultural differences is the first step.

provides a detailed list of recommended strategies to reach this goal. Community/public health nurses need to be aware of health disparities among and within racial and ethnic groups. All nurses should be aware of barriers to achieving optimal health and methods to facilitate attaining culturally competent health care for everyone. Recognizing cultural differences is the first step.

Understanding cultural differences

Different cultures have different views and perspectives regarding everyday concepts and normal behavior. Understanding the essential characteristics and differences that give each community its uniqueness and recognizing the different meanings of some key concepts in different cultures is useful for nurses who practice in multicultural health care settings (Andrews & Boyle, 2008; Galanti, 2004; Giger & Davidhizar, 2004; Leininger & McFarland, 2006; Purnell & Paulanka, 2008; Spector, 2008).

Time and Space

People perceive and use time in different ways: linear or circular. A linear view sees time as a straight line with a beginning and an end. A circular view sees time as a never-ending unity that repeats itself and is part of a continuous whole. Western health care providers tend to view time in a linear way, divided into segments of minutes, hours, days, weeks, and so on. In the United States, we wear watches, and our watches are synchronous with those of others. Our work day begins and ends at a specific time. We keep appointments on time. Because time is money and is in limited supply, we are urged to both work and play rapidly, accurately, and smartly. We admire people who make good use of their time and control their time well.

People in other parts of the world perceive time differently. They view time as being circular (continuous and never ending). Time may be seen as a gift to be enjoyed rather than a limited commodity to be used. People with this view of time may not have or use a watch, may not be concerned about punctuality, and may not feel stressed to do chores at a set time. If time is a gift to be enjoyed, practically anything may take precedence over a clinic appointment, a nurse’s visit, or a day at school or work.

Individuals and groups also differ in time orientation with regard to health planning. Cultural groups with a past-time orientation, for example, many Asian Americans, tend to lean toward traditional approaches to healing. Persons with a predominantly present-time orientation, for example, African Americans, Native Americans, and Hispanics, may be less able to look toward the future and practice preventive health measures. Pain, dysfunction, or limitations cue the search for treatment. If these cues are absent, a present-orientated person might not appreciate the need for treatment to avoid a future consequence. For example, a middle-aged African American woman with hypertension may be unable to see the need for controlling blood pressure through medication to prevent a future problem such as stroke. By contrast, the middle-class white American culture tends to be future oriented as reflected by its emphasis on punctuality, technology, and prevention. Time is structured and scheduled, including leisure time, which is often planned ahead.

Community/public health nurses and other health care professionals should be aware that clients may have a time perspective that is different from their own. Some African Americans and Mexican Americans believe that time is flexible and that activities will start on their arrival. There is no need to rush to an appointment; a delay is acceptable. If this perception is the usual one in the community, community/public health nurses should incorporate this information in planning program activities.

How human beings view and structure space differs among cultures in ways that are as profound and important as are the differences in how time is viewed and structured. Space is linked with issues of territoriality, living, work and health care arrangements, touch, sound, and smell. Space as a physical boundary or territory is an important concept; just as animals protect their territory, so do humans (Giger & Davidhizar, 2004; Leininger & McFarland, 2006).

Culture determines the amount of personal space an individual requires. Some cultures are comfortable with very little distance between people; others are more comfortable with a separation of several feet. When individuals from different cultures interact, one may violate the other’s personal space. Standing too close to another person can precipitate feelings of anger or fear in the person who feels that his or her space is invaded. Hall (1963) identified four different relational spaces:

The distance in each relational space varies widely, depending on the cultural group’s spatial orientation.

In some cultural groups, persons who own land mark their properties with fences to separate them from those of their neighbors. Some cultures perceive land as belonging to everyone and to no one in particular and would not think of putting up fences. Some cultures value uniformity; others value diversity. Although the United States places great emphasis on individual freedom and creativity, many U.S. towns have covenants that restrict the individual’s right to alter his or her property in any visible way that is unacceptable to the community in general.

How people construct and use public space is an important consideration when nurses conduct community meetings. Various cultural groups perceive space as more or less formal, which can create problems among them. For example, in one nursing home, Americans of African descent used the shared lobby on each floor as formal public space and dressed accordingly. Americans of European descent, in contrast, used the shared space informally, wearing slippers, robes, and even hair curlers.

When in a client’s home, the nurse is a guest and must be aware of how space is structured and used in that home. Some rooms in the house may be reserved only for family and close friends, and the nurse must be aware of cues regarding public and private space. In working with people from a culture that is different from his or her own, the nurse has an obligation to discover how, in general, the client’s cultural group perceives and uses space and how to recognize limit-setting cues.

Communication

Communication is an essential component of any nurse–client interaction. The effectiveness of communication depends on each party’s clear understanding of the meaning of each message. The process of communication includes both verbal and nonverbal components and may be influenced by hierarchic relationships, gender, and religion.

Verbal Communication

Language is an important tool in nursing and in establishing a nurse–client relationship. The gathering of accurate information related to health care beliefs, illness, and care measures is critical. Ineffective communication may lead to misunderstandings. These misunderstandings may result in failure to identify and access existing health services; difficulty with appointment scheduling; inaccurate or incomplete information relevant to health status; and inappropriate follow-up and follow through with recommended treatment. Ineffective communication can result in client dissatisfaction with health care services and reluctance to return to the health care setting (cf. Andrews & Boyle, 2008; Galanti, 2004; Giger & Davidhizar, 2004; Leininger & McFarland, 2006; Munoz & Luckman, 2005; Purnell & Paulanka, 2008; Smedley et al., 2003; Spector, 2008; Wilson-Stronks & Galvez, 2007).

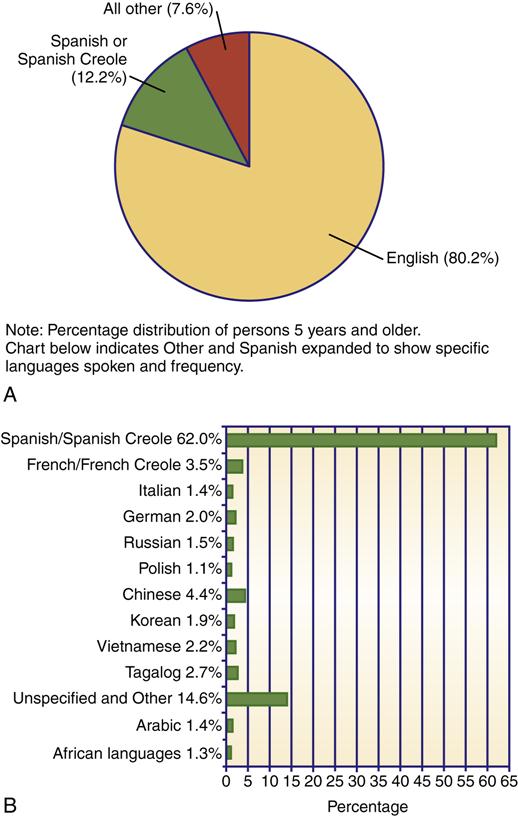

Language barriers are one of the greatest obstacles to health care among culturally diverse groups. In the United States, approximately 56 million people speak a language other than English at home, and at least 39 different languages are in use (Figure 10-3). Approximately 35 million are speakers of Spanish, and of those, approximately 14 million report that they speak English less than very well (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2010b; U.S. Census Bureau, 2011b).

Cultural and Linguistic Competence

Cultural and linguistic competence refers to the ability of health care providers and organizations to understand and respond to the cultural and linguistic needs of clients during health care encounters. Laws and federal guidelines pertaining to provision of language services, means of accessing language services, and the appropriate use of language services are essential information for the community/public health nurse. In response to the need to facilitate culturally competent health care, the Office of Minority Health published National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) to be implemented in health care settings (USDHHS, 2001a). These standards provide a blueprint for organizations to follow in building cultural and linguistic competence in their workforces and organizations. Box 10-3 summarizes the sections relating to direct client–provider conversations. The complete CLAS standards are available on the book’s website as Website Resource 10B. ![]()

Linguistic competence is addressed by four of the standards. CLAS standards require health care organizations to offer language assistance services free to each client or consumer with limited English proficiency. Bilingual staff and interpreter service are preferred. Other options include face-to-face interpretation provided by trained staff or contract or volunteer interpreters.

Community/public health nurses must establish an effective means of communication with individuals with limited English proficiency. The use of interpreters and interpreter services is one means. However, the interpreter–client interchange may be affected by differences in dialects within the same regions; cultural, political, or religious rivalry between tribes, nations, regions, or states; and age, gender, and socioeconomic status. For example, a client and an interpreter both come from Laos; however, one is Hmong and the other is not. Because of their different tribal affiliations, each views the other with suspicion, which makes the interpretation process difficult.

Issues of status, age, gender, and privacy must be considered when selecting an interpreter. For example, in some cultures, conversations between unrelated men and women are strictly regulated or forbidden. All attempts should be made to choose interpreters with characteristics as close as possible to those of the client. If a formal interpreter is not readily available, telephone services are acceptable. Telephone services provide interpreters for most languages. The nurse and client speak into separate telephones, and the interpreter translates for each party. Accurate interpretation of client responses is critical. The CLAS standards require that organizations ensure the competence of interpreters. Family or friends should not be used as interpreters except in emergencies or at the specific request of the client. Using family members or friends would cause breach of confidentiality, and these individuals may not give an impartial interpretation of the intended message. Minor children should not be used as interpreters, even in situations in which the clients are their parents.

Community/public health nurses who routinely care for clients with English language difficulties should be prepared in advance if no interpreters are available. The best strategy is for the nurse to become proficient in the language of the clients. Another strategy is the use of a word board or index cards with essential words or phrases in the client’s own language. For example, “Where is your pain?” or “When did it start?” Hand motions, miming, or simple touch may be the only available methods of communication; however, these methods are more error prone than are cards or word boards.

Using a considerate approach, addressing the client by formal name, showing genuine warmth, and taking time to establish trust are important. Clients from minority groups cite the lack of time and attention given by health care professionals as one of the most important reasons for their lack of trust in the health care system (Government Accountability Office, 2005; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010). The nurse may wish to start with safer topics, use open-ended formats, and elicit opinions and beliefs to begin the dialogue. Nonverbal clues and specific behavior during conversations should be noted. The diversity of voice volume and tone used by different cultural groups should be appreciated. Anglo Americans and African Americans may be perceived as loud and boisterous because of their voice volume. African Americans who speak black English, Gullah (a Creole blend of Elizabethan English and African languages), or other African dialects exclusively may be misunderstood as being poorly educated or unintelligent (Campinha-Bacote, 1998). Gypsy language tone is normally loud and argumentative, even in normal conversation. Arab Americans tend to use an excited speech pattern that may be misunderstood as anger; a loud voice may merely indicate the importance of the message. The Chinese language is very expressive and may come across as loud and abrupt to others (Chin, 1996).

Health Literacy Skills

Health literacy skill refers to the ability to read and understand instructions on prescription and medicine bottles, appointment slips, informed consent documents, insurance materials, and client educational materials. Health illiteracy is a frequently overlooked and underemphasized barrier to health care in racial and ethnic minority populations (Burroughs et al., 2002). An estimated 90 million American adults possess low health literacy skills. Low literacy is more frequently noted among persons of low socioeconomic status, the poorly educated, older adults, U.S.-born ethnic minority persons, immigrants, and persons who are disabled. Low health literacy continues to be a barrier for racial and ethnic minorities. (See Chapter 20 for ways to determine and reduce the reading level of health materials.)

The CLAS standards require that organizations provide educational materials and forms in the commonly encountered languages. Community/public health nurses must ensure that materials in alternative formats are developed for individuals who cannot read or who speak nonwritten languages (e.g., sign language) and for persons with sensory, developmental, or cognitive impairments. Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 requires that all organizations that receive federal financial assistance ensure that persons with limited English proficiency have meaningful linguistic access to the health services that these organizations provide (USDHHS, 2001a).

Community/public health nurses must perform an adequate assessment of literacy skills to reduce the potential for medical errors caused by a client’s language difficulties. Developing client educational materials that are culturally congruent with the target population and at an appropriate reading level is important. Many of the educational materials that are specifically targeted at minorities do not reflect the cultural values of the targeted groups, and few are written at a reading level suitable for persons with low literacy skills. Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA) is a tool that helps assess a client’s ability to perform health-related tasks that require reading and computational skills, such as taking medications, keeping appointments, appropriately preparing for tests and procedures, and giving informed consent.

Nonverbal Communication

Nonverbal communication patterns are important to the communication process. Nonverbal communication patterns vary widely among cultures and ethnic groups. Understanding and appropriate use of touch, silence, eye contact, greetings, and body language are vital to the nurse–client interaction. The nurse’s capacity to assist the individual, family, and community to reach the desired health outcomes may be impaired by his or her inability to understand and accurately interpret the nonverbal patterns of the ethnic and cultural groups that he or she serves (cf. Munoz & Luckman, 2005; Purnell & Paulanka, 2008; Spector, 2008; Wilson-Stronks & Galvez, 2007).

Touch

Use of touch in the communication process is culturally dependent and varies significantly from culture to culture. Some cultures seek bodily contact; others carefully avoid contact. For example:

• Greetings among many Americans include traditional handshakes or hugging.

• Among Native American Navajos, touch is unacceptable except when one knows the person well or when it is part of therapeutic treatments (Still & Hodgins, 1998).

• For Nigerian Americans, touching or casual hand holding between members of the same or opposite sex usually signals friendship (Andrews & Boyle, 2008).

• In some Middle Eastern cultures, women do not shake hands with men, nor do men and women touch each other outside of marriage (Andrews & Boyle, 2008).

• Afghan and Afghan American extended family members and close friends often touch each other on the shoulder or leg during conversations and greet with a kiss on each cheek or a hug (Lipson et al., 2004).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree