Promoting Healthy Communities Using Multilevel Participatory Strategies

Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to do the following:

Key Terms

built environment, p. 376

client system, p. 377

community, p. 382

community-based participatory research (CBPR), p. 374

community health, p. 384

ecological approach, p. 374

focus of care, p. 377

health, p. 377

health behavior, p. 380

health maintenance, p. 381

health promotion, p. 381

illness care, p. 377

illness prevention, p. 381

lifestyles, p. 374

multilevel intervention, p. 374

Photovoice, p. 387

risk appraisal, p. 381

social determinants of health (SDOH), p. 374

—See Glossary for definitions

Pamela A. Kulbok, DNSc, RN, PHCNS-BC, FAAN

Pamela A. Kulbok, DNSc, RN, PHCNS-BC, FAAN

Pamela A. Kulbok earned her doctorate at Boston University and did postdoctoral work in psychiatric epidemiology at Washington University in St. Louis. She was a U.S. Navy nurse; has worked in a visiting nurse service; and has directed a hospital-based home health agency. She is presently Professor of Nursing and Chair of the Department of Family, Community, and Mental Health Systems at the University of Virginia, School of Nursing. Dr. Kulbok is the Principal Investigator of an interprofessional, cross-institution, community-based participatory research project to design a substance use prevention program with youth, parents, and community leaders in a rural tobacco-growing county of Virginia. This study builds on a series of externally funded studies of youth non-smoking behavior. She has taught undergraduate and graduate courses in public health nursing, health promotion research, and nursing knowledge development. Dr. Kulbok has been a leader of public health nursing professional organizations. She was president of the Association of Community Health Nursing Educators (2004-2006) and Chair of the Quad Council of Public Health Nursing Organizations (2004-2005). She recently completed a 4-year term as a member of the American Nurses Association (ANA)—Congress on Nursing Practice and Economics. She was a contributor to the Nursing Social Policy Statement: Essence of the Profession (ANA, 2010). She is an inaugural faculty and faculty fellow, Healthy Appalachia Institute, the University of Virginia’s College at Wise, National Network of Public Institutes, in recognition of contributions to the health of the residents of Southwest Virginia (2009-2011).

Nisha Botchwey, PhD, MCRP

Nisha Botchwey, PhD, MCRP

Nisha Botchwey specializes in community development and neighborhood planning emphasizing local religious and secular institutions and public health promotion. She teaches undergraduate and graduate community development and health courses including Healthy Communities, a seminar exploring the connections between the built environment and health, and available as an online curriculum resource (http://www.builtenvironmentandpublichealthcurriculum.com). She is presently Associate Professor of Urban End Environmental Planning and Public Health Sciences at the University of Virginia. She discussed her focus on approaches to revitalize unhealthy communities, places where the physical and social environments do not enable people to maximize their lives, on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2007 National Broadcast of Public Health Grand Round titled “Healthy Places Leading to Healthy People: Community Engagement Improves Health for All.” Her funded research involves three multidisciplinary collaborations with scholars from the Schools of Nursing, Medicine and Engineering, and with support from the National Institutes of Health and other public and private sources. Dr. Botchwey’s publications are found in a variety of planning, public health, and nursing journals. She serves on local and national advisory boards including the Governing Board for the Association of Collegiate Schools of Planning and is a recipient of numerous awards including Annie E Casey Foundation Junior Scholar (2004), NIH Health Disparities Scholar (2005, 2006), Seven Society as an Outstanding Teacher (2007), and Rockefeller-Penn Fellow (2010).

The pursuit of long, healthy lives through participation in population-focused health programs is essential to achieve the national health vision and goals proposed in Healthy People 2020 (USDHHS, 2009a). Interest in healthy lifestyles is obvious in the accruing epidemiological evidence linking lifestyle and health, and notably in the emphasis on public health programs that address the social determinants of health (SDOH) and healthy lifestyles in populations (Freudenberg, 2007). Virtually all people recognize the need to exercise regularly, maintain their weight at recommended levels, and manage stress in their lives. Despite increased interest in healthy lifestyles, modifiable health-related behaviors are the major contributors to deaths in the United States (NCHS, 2010). For example, tobacco use remains the leading cause of premature deaths with 443,000 deaths annually attributed to cigarette smoking (NCHS, 2010). Nurses, other health professionals, and the public recognize that initiating and maintaining a healthy lifestyle is complex and requires different approaches directed toward individuals, families, communities, populations, and the environments in which they live.

In this chapter, we describe an ecological approach to community health promotion, which integrates multilevel interventions to promote the health of the public. The integrative model of community health promotion (Laffrey and Kulbok, 1999) can help nurses plan care for clients including communities and populations. The model synthesizes knowledge from public health, nursing, and the social sciences. In this chapter, we also define some of the basic concepts that concern nurses and their interprofessional health care partners. We describe the historical underpinnings of these concepts, including definitions of health and health promotion for communities and populations including the SDOH. The concepts of health maintenance, illness prevention, and community are also discussed. These concepts and their linkages determine the direction and methods for nursing practice with communities and populations. The chapter describes studies that illustrate community-based participatory research (CBPR) and multilevel interventions. Applications of the integrative model of community health promotion show that the way nurses view these concepts is important in their approach to practice.

The Ecological Approach to Community Health Promotion

Nurses have long recognized the importance of an emphasis on wellness and health promotion in health care. In public health nursing (PHN) practice, it is clear that many factors, beyond illness, affect the health of individuals, communities, and populations. The biomedical model, in which health is defined as absence of disease, does not explain why some populations exposed to illness-producing stressors remain healthy, whereas others, who appear to be in health-enhancing situations, become ill. Viewing clients from the perspective of the biomedical model alone makes it difficult to identify health potential beyond the absence of disease. For example, most at-risk populations such as the frail elderly have at least one diagnosed chronic disease. Limiting the definition of health potential to the absence of disease, nurses would never perceive this population as healthy. Defining health as the absence of disease is a pessimistic definition; nursing actions can help older and chronically ill persons become healthier if a broader definition of health is used. Nurses can assist clients in identifying their health potential and in planning measures that enhance their health.

Studies show that there is no better way to promote health and improve the quality of life of individuals than through basic healthy habits such as exercising regularly, maintaining a balanced and healthy diet, developing a positive and optimistic outlook, and refraining from smoking (Chowdhury et al, 2010). Directing health care toward helping communities and populations to identify their health potential, and providing care and resources that move communities and populations toward their health potential, are important goals. These actions can improve the health of the overall population and thus decrease the burden of disease in vulnerable populations at the fringe of health care.

Laffrey, Loveland-Cherry, and Winkler (1986) described two perspectives from which the key concepts of nursing science (e.g., person, health, environment) and nursing can be viewed. The disease-oriented perspective views health objectively and defines it as the absence of disease. This perspective assumes that humans are composed of organ systems and cells; health care focuses on identifying what is not working properly with a given system and repairing it. In this context, how clients comply with the recommendations of health professionals forms the basis for health behavior. The second perspective defines health subjectively as a process. Humans are complex and interconnected with the environment. They are different from and greater than the sum of their parts. Health behavior within the health-oriented perspective involves a holistic view of lifestyle and interaction with the environment and is not simply compliance with a prescribed regimen.

Both perspectives support the aims and processes of population-focused nursing. The disease-oriented approach directs nursing toward illness prevention, risk appraisal, risk reduction, prompt treatment, and disease management, whereas the health-oriented approach directs nursing practice toward promotion of greater levels of positive health. Defining health broadly as the life process, taking into account the mutual and simultaneous interaction of humans and their environment, views illness as a potential manifestation of that interaction. Because positive health does not exclude any part of the life process (it includes illness prevention and illness care), it goes beyond the disease perspective to include positive and holistic health (Laffrey and Kulbok, 1999).

Ecological Perspectives on Population Health

Because individuals ultimately make decisions to engage in healthy or risky behaviors, lifestyle improvement efforts have focused typically on the individual as the target of care. Following the health belief model (Rosenstock, 1974), individuals generally concentrate on immediate personal rewards or threats when deciding whether to engage in specific behaviors; in this context, they may convince themselves that their immediate personal risks from certain behaviors such as smoking are low, or that the immediate rewards outweigh the risks. However, from a public health perspective, smoking in the United States has resulted in more than 443,000 deaths annually during 2000 to 2004, and the annual health-related economic losses were approximately 5.1 million years of potential life lost and $96.8 billion in productivity losses (CDC, 2008). Therefore, it is clear that health behaviors extend beyond the individual or the intrapersonal and the interpersonal levels, having multiple determinants both internal and external to individuals and communities, as well as determinants within the society.

For example, adolescents’ decisions not to smoke are associated with their individual attributes (e.g., positive self-image), family characteristics (e.g., parent–child connectedness), aggregate characteristics (e.g., peer influence), and community factors (e.g., living in a tobacco-growing region) (Kulbok et al, 2008b). As a result, interventions to initiate or maintain healthy behaviors have greater potential for success when directed systematically toward the multiple targets of the individual, family, group, community, and society—that is, when they use an ecological approach to community health promotion.

The Social Determinants of Health

Current trends in public health and health promotion emphasize the ecological perspective with interaction between individuals and the environment. The ecological approach also addresses the SDOH (McQueen, 2009) through social networks, organizations, neighborhoods, and communities (Navarro, Voetsch, and Liburd et al, 2007). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), SDOH “are the conditions in which people are born, grow up, live, work and age, including their health. These circumstances are in turn shaped by a wider set of forces: economics, social policies, and politics” (2010, p 1). The WHO is an important contributor to defining and developing strategies to address the SDOH. They outlined ten components of SDOH. (Box 17-1 lists the 10 components.)

There is increasing awareness that to achieve lasting gains in population health, assessments and interventions must be directed to multiple levels of the client system like those outlined in the SDOH. For example, a multilevel analysis of depressive symptoms in a national sample of 18,473 adolescents in the United States (Wight et al, 2005) showed that individual, family, aggregate, and community characteristics accounted for significant differences in adolescent depression. The American Academy of Pediatrics (2005) issued a statement urging pediatricians to increase their partnerships with communities in developing programs to improve child health. Examples of pediatrician-community partnerships (Sanders et al, 2005) include establishing a child health consultant program, working with a community to repair and fund sites to facilitate safe physical activity for children, developing dance programs for overweight and obese adolescent girls, and arranging a program for community leaders to learn about the Medicaid enrollment process. Traditional interventions that target only an individual’s risk or illness are not as effective as interventions and programs developed using an ecological approach that can affect all levels of the client system that contribute to good or ill health (Navarro et al, 2007). More studies are needed to design and test these ecological, multilevel community health interventions.

Farley and Cohen (2005) introduced the curve-shifting principle. This principle complements the ecological model and calls for targeting health interventions at the population level. They built upon representations of the relationship between individual and group behavior (Rose, 1992), with individual behavior being the foundation of the total population distribution. The median of this normal distribution represents prevailing social norms that govern health behavior. Traditional approaches to health behavior interventions for public health problems like obesity focus on the intrapersonal and interpersonal levels for high-risk populations—people at the extremes of the population curve. Although treating high-risk populations may be effective for selected individuals and may move them closer to the center or the prevailing social norm, this approach does little to prevent others from becoming the extremes of the distribution. Therefore, a focus on the total population, not just the high-risk group, with efforts to change the social norm so that everyone is consuming less sugar or participating in more hours of moderate to vigorous physical activity, exemplifies the curve-shifting principle.

Consider another example of the curve-shifting principle involves the built environment. The built environment includes the physical parts of the environment where we live and work (e.g., homes, buildings, streets, open spaces, and infrastructure) (CDC, 2006). Prentice and Jebb (1995) were among the first to report the association between obesity and the built environment by measuring inactivity, car ownership, and television viewing.

Instead of simply teaching children the importance of walking and biking to school, the Safe Routes to Schools initiative improved the environment and the walkability of areas near schools, which correlates with increased local resident walking (Owen et al, 2004). Increased walking among local adult residents is evidence that “…increasing neighborhood walkability may affect people in the larger community, not just schoolchildren” (Watson et al, 2008, p 5). As a result, the population living nearest to walkable areas will walk more, thereby shifting the population social norms about walking and biking, including to school. People’s behavior will change based on targeted interventions to the environment in which they live, a concept advanced by B.F. Skinner, a behavioral psychologist in the 1950s (Skinner, 1978). In following this curve-shifting principle in health promotion and illness prevention, the ecological model works at the population level to shift social norms governing health behavior and ultimately health outcomes.

An Integrative Model for Community Health Promotion

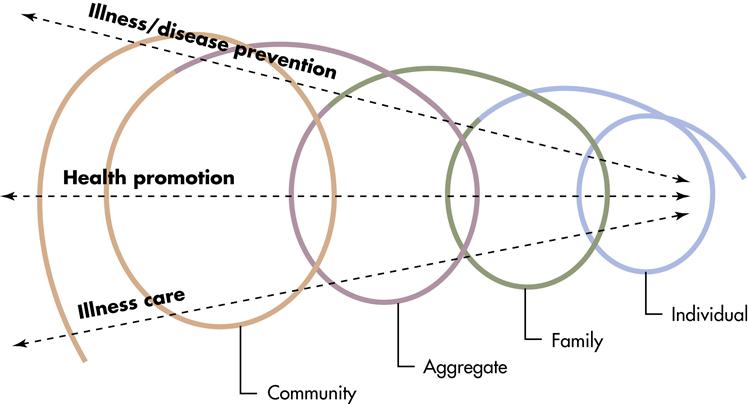

Laffrey and Kulbok (1999) developed a model for community health promotion to guide nursing and health care. The original intent of the model was threefold. First, the model assists nurses to see the continuity of care at multiple levels. Second, it helps nurses describe their own areas of expertise within the complex health care system. Third, the model provides a basis for collaboration and partnership among nurses, other health care providers, and the population. Each of these collaborators brings expertise to the client system. Important assumptions underlying the model include the need for integration of care in the complex health care system; the inseparable nature of individuals, families, aggregates, and community systems; and the maximization of health potential through health promotion interventions. In addition, the model builds upon complementary health and disease perspectives described previously (Figure 17-1). The health perspective focuses on promoting health as a dynamic and positive quality of life and includes the promotion of physical, mental, emotional, functional, spiritual, and social well-being. The disease perspective includes both the care and prevention of illness (disease and disability) and focuses on reducing risks and threats to health. Although some clinical strategies may be similar in the two perspectives, their ultimate goals differ fundamentally. The difference in these two perspectives is seen in the specific purpose of nursing and health care, as it is applied to health promotion, illness prevention, or illness care.

The integrative model (Laffrey and Kulbok, 1999) includes two major dimensions: client system and focus of care. The client system is multidimensional with nursing and health care targeting the multiple levels of clients. The simplest level of the client system is its most delimited target, the individual. When the individual is the client, the environment includes the family, the broader aggregate, and the community of which the individual is a part. The nurse and health care provider are concerned with how these environments affect the individual as well as his or her health.

Each succeeding level of the client system is more complex, since the client can also be the family, an aggregate, or the community. The aggregate and community make up the environment for the family, and the community is the environment for the aggregate. Examples of different types of assessments and interventions appropriate at each level of client within the system are discussed later in this chapter. It is important to remember that community-oriented care is holistic in nature and is population focused in that it addresses multiple levels of clients and multiple levels of care within the total system. The integrative model of community health promotion is consistent with the ecological approach described earlier, which addresses SDOH through social networks, organizations, neighborhoods, and communities (Navarro et al, 2007).

Focus of care in the integrative model includes health promotion, illness (disease or disability) prevention, and illness care. Each focus is appropriate for some aspects of nursing and health care. It is even more important to remember that the goal of health care is a healthier community, achieved through health promotion interventions. No matter where care begins, it ultimately leads to health promotion of the community. It underscores the need for nurses and health care providers to have a good understanding of care requirements at all of the client levels. The individual, family, aggregate, and community each have characteristics, strengths, and health needs that are unique and that differ from those at the other levels.

The integrative community health promotion model reflects the basic beliefs and values of holistic nursing and health care practice. The model depicts continuity and expansiveness of the client systems and foci of care. Health promotion is the central axis, or core, of the model. At its narrowest focus, individuals receive illness care. According to the model, at the broadest level of care, nurses work with community leaders, other community residents, and health professionals to plan programs to promote optimal health for the community and its people. The goals of nursing and health care actions in the integrative model, at any client level from the individual to the community, are to identify health potential and achieve maximal health. To achieve these goals it is essential to have an active partnership between the nurse, health care providers, and the client system. By facilitating an active partnership with the client system, whether the focus of care is health promotion, illness prevention, or illness care, nurses involve clients in each step of the process of managing care from the assessment of their health needs and resources to implementation and evaluation of outcomes.

Historical Perspectives, Definitions, And Methods

Health and Health Promotion

Historical Perspectives on Health

Health is the key term in an ecological approach to community health promotion. Beginning with Florence Nightingale’s efforts to discover and use the laws of nature to enhance humanity, nursing has always taken an active role in promoting the health of communities and populations. The way one defines health shapes the process of nursing and health care, including

making decisions about what to assess, with what level of client, and how to evaluate the outcomes of care. Health, defined as alleviating an individual’s illness symptoms, involves assessment of the duration, intensity, and frequency of specific symptoms. Intervention focuses on symptom relief and treatment of the cause of symptoms. Evaluation consists of determining the extent of symptom alleviation. On the other hand, health defined as maximizing a community’s physical recreation opportunities, involves assessment of existing recreation facilities, accessibility to the population, and beliefs and knowledge related to recreation and land use in the community.

The holistic view of health is not new. The ancient Greeks viewed health as the influence of environmental forces such as living habits; climate; the quality of air, water, and food on human well-being; and healing from illness. As such, they represented health in two sisters, Hygeia and Panacea, symbolizing opposite approaches to the attainment of health; Hygeia, referring to hygiene, cleaned people and the world to protect health, whereas Panacea magically restored mortals to health one at a time. Certain activities of daily living, such as exercise, were essential to the maintenance of health. Box 17-2 lists health perspectives as they emerged over time. Scientific medicine emerged slowly, and resistance to scientific discoveries, such as to the germ theory of disease, hindered the application of these discoveries to medical practice. With the development of the scientific approach toward disease in the twentieth century, professional care took precedence over self-care. During the last five decades, the idea of self-care as derived from a positive idea of health has reemerged to compete with professional care. Some proponents of self-care emphasize lay diagnosis and self-treatment, whereas others focus on teaching people how to work with their health care providers. As a result, health care system changes include the renegotiation of roles and emphasize collaboration between consumers and providers.

Many health professionals contend that individuals are in a position to produce health. Fuchs (1974) suggested that the “greatest potential for improving health lies in what we do and don’t do for and to ourselves” (p 55). In the political arena, LaLonde introduced a similar conclusion in A New Perspective on the Health of Canadians (1974). LaLonde identified four major determinants of health: human biology, environment, lifestyle, and health care. In 1976, policy makers in the United States echoed these ideas and supported efforts to improve health habits and the environment as the best hope of achieving any significant extension of life expectancy (USDHEW, 1976, p 69). Box 17-3 lists some landmark initiatives in health promotion and disease prevention.

The U.S. Public Health Service established the first national objectives involving disease prevention, health protection, and health promotion strategies in the surgeon general’s Healthy People report (USDHEW, 1979). Disease prevention strategies focused on services such as family planning and immunizations delivered in clinical settings. Health protection strategies included environmental measures to “significantly improve health and the quality of life for this and future generations of Americans” (USDHEW, 1979, p 101), such as occupational health and accidental injury control. Health promotion strategies focused on achieving well-being through community and individual lifestyle change measures. The Healthy People report (USDHEW, 1979) also described inherited biological factors, the environment, and behavioral factors as the three categories of risks to health, which are identical to LaLonde’s first three major determinants of health.

As described in Chapter 2, the health objectives for the nation outlined in Healthy People 2010 built on initiatives that have been pursued since 1980. Designed for use by individuals, communities, states, and professional organizations, these health objectives provided a guide for programs to improve health. Nursing organizations participated in the development of the national health objectives and priorities. These organizations included the Quad Council of Public Health Nursing Organizations: the Association of State and Territorial Directors of Nursing (ASTDN), the American Nurses Association (ANA) Council on Nursing Practice and Economics, the Association of Community Health Nursing Educators (ACHNE), and the PHN Section of the American Public Health Association (APHA).

The release of the Healthy People 2020 Framework in 2009 included a national vision, mission, and overarching goals. The four overarching goals emphasized prevention, health equity, environments conducive to health for all, and healthy development across the lifespan. This Healthy People 2020 Framework preceded the release of the Healthy People 2020 goals, objectives, and action plans for the nation in 2010. Information on the development process and launch of Healthy People 2020 is available at http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/default.aspx.

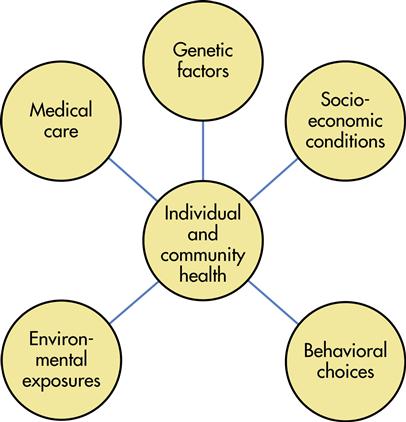

The idea that the health of communities and populations is shaped by multiple determinants has been reinforced in the national (IOM, 2002, 2006) and international (CSDH, 2008; McQueen, 2009) health policy literature. The major determinants of health have been expanded (Figure 17-2) to include “. . .interactions among genes, socioeconomic circumstances, behavioral choices, environmental exposures, and medical care” (Hernandez, 2005, p 64). Although recent trends reveal improvement in SDOH such as healthier living conditions and a decrease in smoking, these positive trends are associated with persistent socioeconomic disparities worldwide (CSDH, 2008).

Definitions of Health

The WHO (1958) reflected a holistic perspective in its classic definition of health as a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease and infirmity. In 1975, Terris noted that epidemiologists considered the WHO definition to be “vague and imprecise with a Utopian aura” (p 1037). Terris expanded the definition: “Health is a state of physical, mental and social well-being and the ability to function and not merely the absence of illness and infirmity” (Terris, 1975, p 1038). In deleting the word “complete” and adding “ability to function,” Terris placed the WHO definition in a more realistic context, providing a useful framework for health promotion.

Smith (1981) suggested that the “idea of health” directs nursing practice, education, and research. She observed that health was a comparative concept, allowing for “more” or “less” health along a health-illness continuum. Smith proposed four models of health, ordered from narrow and concrete to broad and abstract: clinical health, or the absence of disease; role performance health, or the ability to perform one’s social roles satisfactorily; adaptive health, or flexible adaptation to the environment; and eudaemonistic health, or self-actualization and the attainment of one’s greatest human potential.

Population health is a term widely used in IOM reports on the future of the public’s health (IOM, 2002) and on educating public health professionals (IOM, 2003). Population health is defined as “the health of the population as measured by health status indicators and as influenced by social, economic, and physical environments, personal health practices, individual capacity and coping skills, human biology, early childhood development and health services” (Federal, Provincial, Territorial, Advisory Committee on Population Health, 1999, cited in IOM, 2002, pp xii-xiii). This definition of population health is consistent with the ecological approach to community health promotion and the SDOH.

It is important for nurses and health care providers to reflect on their own definition of health and recognize how their health definition influences the care they provide. Likewise, it is equally important for nurses to assess clients’ personal health definitions. Only through knowledge of one’s own health definition, together with assessment of clients’ health definitions, can nurses create interventions tailored to achieve the clients’ health goals. Nurses and health care providers who emphasize health promotion and population health that is congruent with the beliefs, health definitions, and goals of the population acknowledge the importance of illness prevention. Moreover, nurses must strive to understand health policies and the consequences of these policies on vulnerable populations whose living conditions may include few determinants of good health. (See Box 17-1.)

Definitions of Health Promotion

Health promotion is an accepted aim of nursing and health care, although explicit definition of health promotion and differentiation from disease prevention or health maintenance is rare. Leavell and Clark (1965) strongly influenced the evolution of health promotion and disease prevention strategies through their classic definitions of primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of prevention that were rooted in the biomedical model of health and epidemiology. The application of preventive measures, according to Leavell and Clark, corresponds to the natural history or stages of disease (see Table 12-3). Primary preventive measures apply to “well” individuals in the pre-pathogenesis period to promote their health and to provide specific protection from disease. Secondary preventive measures apply to diagnose or to treat individuals in the period of disease pathogenesis. Tertiary prevention addresses rehabilitation and the return of people with chronic illness to a maximal ability to function (see Levels of Prevention box).

Even though primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of prevention had their origins in the medical model, Leavell and Clark (1965) moved beyond the medical model. They conceptualized primary prevention as two distinct components: health promotion and specific protection. Health promotion focuses on positive measures such as education for healthy living and promotion of favorable environmental conditions as well as periodic examinations including, for example, well-child developmental assessment and health education. Specific protection includes measures to reduce the threat of specific diseases, such as hygiene, immunizations, and the elimination of workplace hazards.

Health promotion and specific protection, when used as subconcepts of primary prevention, appear to stem from a definition of health as the absence of disease. However, differences in health promotion and specific protection strategies suggest that they are not the same. Some terms used to describe health promotion are linked to a positive view of health (e.g., health habits), whereas other terms are linked to the negative view of the absence of disease (e.g., disease or illness prevention). Using the terms health promotion, health protection, and disease prevention interchangeably, as indicators of preventive behavior, increases the confusion in terminology (Kulbok et al, 1997).

The WHO described health promotion as “the process of enabling people to increase control over, and improve their health” (WHO, 1984, p 3). According to the Ottawa Charter, health promotion combines both individual-level and community-level strategies including “building healthful public policy, creating supportive environments, strengthening community action, developing personal skills, and reorienting health services” (Bracht, 1990, p 38). Health is a resource for daily living. For individuals or communities to realize physical, mental, and social well-being, they must become aware of and learn to use the social and personal resources available within their environment.

Kulbok (1985) proposed a resource model of health behavior, which viewed social and health resources as correlates of positive health behaviors. Two major findings in studies to test this model (Kulbok, 1985; Kulbok et al, 1997) were: (1) health behavior is multidimensional, and there are several categories of health behavior including positive behaviors (e.g., a nutritious diet, exercise) and avoidance behaviors (e.g., non-user of tobacco, alcohol, or drugs), and (2) different health and social resources are associated with different health behaviors. Strategies to promote well-being focus on practicing new healthy behaviors or changing unhealthy behaviors. Successful intervention is more likely when nurses and health care providers understand how social and health resources relate to health behaviors of communities and populations, what social and health resources are available to communities and populations, and how these resources may affect behavior choices.

Laffrey (1990) differentiated between the terms health promotion, illness prevention, and health maintenance. Health promotion is behavior directed toward achieving a greater level of health. Illness prevention is behavior directed toward reducing the threat of illness, and health maintenance focuses on keeping a current state of health. Applying these definitions requires that nurses and health care providers assess not only behavior, but also the basis for choosing to perform a given behavior. In a study of men and women with and without chronic diseases living in a community, Laffrey (1990) asked subjects to identify their five most important health behaviors; for each behavior reported, subjects indicated three reasons for performing the behavior. For example, subjects exercised because regular, vigorous exercise produced a more energetic feeling and the ability to function at a higher level (a health promotion behavior); they exercised because of risk factors for coronary artery disease (an illness-preventing behavior); and they exercised regularly to maintain weight (a health maintenance behavior). The participants in this study characterized their health behaviors according to all three constructs, thereby demonstrating the complexity of health and illness behavior.

In 1997, Kulbok et al reported a content validity study of five national health promotion experts and found differences between the terms health promotion and health promotion behavior. The group of experts defined health promotion as activities undertaken by health professionals to promote health in their clients, and the term included health education and counseling. Health promotion behavior, on the other hand, is behavior that an individual performs to promote his or her health and well-being. Kulbok et al (2003) subsequently developed and tested the Multidimensional Health Behavior Inventory based on this broad definition of health and health promotion behavior.

Pender, Murdaugh, and Parsons (2011) also differentiated between health-protecting and health-promoting behaviors. Health protection refers to behaviors that decrease one’s probability of becoming ill, whereas health promotion refers to behaviors that increase well-being of either an individual or a group. According to Pender et al (2011) although health protection and health promotion are complementary, health promotion is a broader concept that encompasses individuals, communities, and populations.

In summary, there is considerable evidence of agreement regarding a positive view of health underlying health promotion activities directed toward individuals, communities, and populations. For example, the WHO’s definition of health promotion as a process, the resource model of health behavior (Kulbok, 1985; Kulbok et al, 2003), the notion of health behavior choices by Laffrey (1990), the definition of health promotion by Pender et al (2011), and the 10 components of the SDOH (WHO, 2010) are all grounded in the perspective of positive health. In each of these models or approaches, health promotion activities involve a broad, holistic view of lifestyle as a process as well as simultaneous interaction with the social and physical environments. Clearly, health promotion and population health are consistent with the goals of PHN and health care.

Assessing Health within Health and Illness Frameworks

Illness Prevention

Risk appraisal is widely used to help individuals and populations improve their health practices, thereby reducing their risk of disease. In a health risk appraisal, individuals supply information about their health practices, demographic characteristics, and personal and family medical history for comparison with data from epidemiologic studies. These comparisons are then used to predict individuals’ risks of morbidity and mortality and to suggest areas in which disease risks may be reduced. Thus, risk appraisal is a type of secondary prevention used for screening to prevent or detect disease in its earliest stages and is one of several approaches to health assessment (Babor, Sciamanna, and Pronk, 2004). The evidence base for risk appraisal is the relationship of risk factors, disease, and the effectiveness of interventions to reduced mortality and risks of mortality. Box 17-4 lists the three most common types of health risk appraisal approaches used to assess individuals. Each type of risk appraisal is complex, and we describe only the basic concepts and selected procedures in this chapter. The references cited at the end of the chapter provide explanations that are more complete. Refer to Appendix D for an example of a risk appraisal tool.