1. Define, spell, and pronounce the terms listed in the vocabulary. 2. Apply critical thinking skills in performing patient assessment and care. 3. Distinguish among the government agencies that regulate drugs in the United States. 6. Explain the medical assistant’s role in preventing drug abuse. 7. Differentiate among a drug’s chemical, generic, and trade names. 8. Describe the use of drug reference materials. 9. Explain the five pregnancy risk categories for drugs. 10. Define the five medical terms used to describe the clinical use of drugs. 11. Cite safety measures for the use of over-the-counter (OTC) drugs. 12. Diagram the parts of a prescription. 13. Demonstrate the ability to transcribe a prescription accurately. 14. Relate the principles of pharmacokinetics to drug use. 15. Describe factors that affect the action of a drug. 16. Compare the therapeutic classifications of medications. 17. Differentiate among commonly used herbal remedies and alternative therapies. 18. Examine the role of the medical assistant in drug therapy education. angina pectoris (an-ji′-nuh/pek′-tuh-ruhs) Spasmlike pain in the chest caused by myocardial anoxia. bronchodilator (brahn-ko-di′-la-tuhr) Drug that relaxes contractions of the smooth muscle of the bronchioles to improve lung ventilation. cirrhosis (suh-ro′-suhs) Chronic, degenerative disease of the liver that interferes with normal liver function. colloidal (kah-loid′-uhl) Pertaining to a gluelike substance. generic Medication that is not protected by trademark. hypercholesterolemia (hi-per-kuh-les-tuh-ruh-le′-me-uh) Elevated blood levels of cholesterol. metabolic alkalosis Condition characterized by significant loss of acid in the body or an increased amount of bicarbonate; severe metabolic alkalosis can lead to coma and death. over-the-counter (OTC) drugs Medications sold without a prescription. spermicide (spuhr′-muh-side) Chemical substance that kills sperms cells. therapeutic range The blood concentration of a drug that produces the desired effect without toxicity. tinnitus A noise sensation of ringing heard in one or both ears. Kathy Augustino, CMA (AAMA), was hired recently to work for a primary care physician in her hometown. Her responsibilities include administering medications to a wide range of patients. To give patients medications correctly and safely in the ambulatory setting, she must understand the basic principles of pharmacology. While studying this chapter, think about the following questions: • What should Kathy know about the management of controlled substances in the ambulatory care setting? • If Kathy is not familiar with a medication, how can she learn about the properties of the drug? Pharmacology is the broad science of the origin, nature, chemistry, effects, and uses of drugs. Clinical pharmacology is the study of the biologic effects of a drug used as a medical treatment and the actions of a drug in the body over time, including the rate at which it is absorbed by body tissues; where it is distributed or localized in the tissues; the route by which it is excreted; and its toxicity, or poisonous effect. Medical assistants must have a general understanding of the types of drugs available and their uses. For every medication administered, a medical assistant must understand the drug’s action, typical side effects, route of administration, and recommended dose, as well as the individual patient factors that can alter the drug’s effect and elimination. Drugs are constantly being developed and released for patient treatment; therefore, medical assistants must continually update their knowledge of specific drugs used in the ambulatory care setting. Correct management of drug administration and patient education are crucial factors in providing safe drug therapy for all patients. Several federal agencies combine forces to regulate, safeguard, and manage the development and use of medications in the United States. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA), a division of the Department of Health and Human Services, regulates the development and sale of all prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) drugs. Pharmaceutical companies developing new medications must gain FDA approval before the drugs can be sold to consumers. The approval process begins with chemical testing in the laboratory and progresses to toxicity testing in laboratory animals, and finally to human clinical trials, which involve volunteers who participate in controlled drug studies. Only one of 10 new drugs ever reaches the clinical testing phase. If the drug is found to have an acceptable benefit-to-risk ratio (i.e., it is effective without causing an unacceptable degree of harm to the user), the FDA approves the medication for release. The original manufacturer of the drug is awarded copyright protection on that particular chemical compound for 17 years; this means that during the 17-year period, other pharmaceutical companies cannot produce generic copies of the drug. Besides approving new drugs for the marketplace, the FDA establishes manufacturing standards for drug purity and strength and ensures that generic brands are effective and safe. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was established in 1973 as part of the Department of Justice to enforce federal laws regarding the use of illegal drugs. According to the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), which was passed in 1970, a drug or other substance that has the potential for illegal use and abuse must be placed on the controlled substance list. Any new medication with an action similar to a drug already on the controlled substance list also is considered to have the potential for abuse. Most controlled drugs provide significant assistance to patients in need of their particular actions, such as pain relief or anesthesia for surgery. However, certain guidelines must be followed to comply with the storage of controlled substances, their record keeping, and security requirements. In addition, federal law requires that all medical personnel, including medical assistants, share the responsibility for managing controlled substances on site. Precautions must be taken to monitor patients’ drug use, protect prescription pads, maintain the records required by law, and report any known or suspected drug diversion or theft. According to the guidelines set forth in the CSA, controlled substances are divided into five sections, or schedules, depending on their addictive abilities and likely degree of abuse. The classifications range from Schedule I drugs, which are illegal and cannot be prescribed, to Schedule V medications, which have the least potential for addiction and abuse (Table 33-1). TABLE 33-1 Classification of Controlled Substances Every medical practice that stores and administers medications that fall into any of the schedule categories should have a copy of the controlled substances regulations. This list can be obtained from the regional DEA office. It is also important to ensure that the office is included on the DEA’s mailing list, so that the practice receives updates as drugs are added, deleted, or moved from one schedule to another. Specific CSA regulations govern the record keeping, physician registration, and inventory of controlled substances. Complete, accurate records on the purchase and management of scheduled drugs in the ambulatory care setting must be maintained. These records must be kept separate from the patient’s medical record for 2 years and must be readily available for inspection by the DEA at all times. Each time a controlled substance is dispensed and administered in the office, documentation of that process includes the number of doses of the drug on site both before and after the medication is dispensed. Medical practices that dispense and administer controlled substances on site use forms developed for this purpose. Any discrepancy in the count of the medication available must be documented and co-signed by two employees. Every physician who prescribes or has controlled substances on site must register with the DEA for a Controlled Substance Registration Certificate. The physician receives a specific DEA registration number that must be included on all controlled substance prescriptions. The certificate is renewable every 3 years and is specific to a particular site of practice. Therefore, if the physician dispenses or prescribes scheduled drugs at more than one site, a DEA registration number must be obtained for each site. All controlled substances must be stored in a safe or immovable locked cabinet, and the keys must be kept in a secure location. Prescription forms should be kept out of areas used by patients and preferably secured in an area that prohibits unauthorized or illegal use. All DEA forms used by the facility to order controlled substances also must be kept in a locked area. Many ambulatory practices no longer keep controlled substances on site. However, if drugs are lost or stolen, the incident must be reported immediately to the regional DEA office and to local law enforcement authorities. If a controlled substance is damaged or must be discarded (e.g., a pill falls to the floor during dispensing), two employees must be present to witness the medication being flushed down the sink or toilet, and both must document the procedure on the controlled substance inventory form used by that office. If a large quantity of scheduled drugs must be discarded, the local DEA office should be contacted for guidance. Individual states also may regulate controlled substances; therefore, it is essential that medical assistants know their state’s legal requirements. Specific guidelines apply to prescription orders for controlled substances: Other specific rules may apply, depending on the schedule to which the prescribed controlled substance is assigned. The symbols C-II, C-III, C-IV, and C-V are used to indicate the specific schedule: • Schedule II (C-II) prescriptions: • In certain states, must be provided as multiple-copy prescription order forms • Schedule III (C-III) and IV (C-IV) prescriptions: • May be ordered orally or in writing • May be refilled up to five times within 6 months of the original order • Schedule V (C-V) prescriptions: • May be ordered orally or in writing • May be refilled up to five times within 6 months of the original order • Depending on the state, may be dispensed by the pharmacist without a prescription Any drug, from aspirin to alcohol, can be misused or abused. The use of illegal and legal drugs has increased tremendously. Treatment programs for drug abuse are available throughout the United States for people from all walks of life. Programs include detoxification, rehabilitation, and long-term rehabilitation maintenance. Medical assistants may encounter patients who are misusing or abusing drugs. It is important to be alert to the symptoms of drug dependence and to notify the physician when you suspect that a patient, or a co-worker, may have a problem with drug or alcohol dependency. Drug misuse is the improper use of common drugs that can lead to dependence or toxicity. Examples of people with chronic dependencies include those who cannot have a bowel movement unless they take a laxative; those who have used nasal decongestants for so long that they cannot breathe without the use of nasal sprays; and those who take so many antacids that they suffer systemic metabolic alkalosis. Drug abuse is the continuous or periodic self-administration of a drug that could result in addiction (physical dependence). Drug dependency is the inability to function unless under the influence of a substance; it may be psychological or physical. Psychological dependency is the compulsive craving for the effects of a substance. Habituation is a mild form of psychological dependency, such as the need for caffeine. Physical dependency, or addiction, is a person’s need to use a substance continuously so that the body can function, and also to prevent physical discomfort. This type of dependency occurs when abused substances produce biochemical changes in cells and tissues, most commonly in the nervous system. When a substance that causes physical dependency is discontinued, withdrawal symptoms occur. Withdrawal symptoms may be mild or serious, leading to convulsions and possibly death. Regardless of the type of drug abused, it will have two effects on the person: acute and chronic. The acute effect is what the person feels when intoxicated, or directly under the influence of a particular substance. Chronic effects include the temporary or permanent physical and mental changes that result from long-term abuse. Medical assistants often must answer patients’ questions about drug abuse. The medical assistant should read and keep up to date on drug-related issues. Pamphlets and agency referral names should be available for patients. In addition, patients’ concerns and questions about drug abuse should be conveyed to the physician. A single drug may have up to three names: a chemical name, a generic name, and a trade name. The chemical name represents the drug’s exact formula. For example, the chemical name of the analgesic acetaminophen is N-(4-hydroxyphenyl). Acetaminophen is the generic name, and the trade name is Tylenol. All drugs are assigned a generic, or nonproprietary (official), name. This name is much simpler than the chemical name, and it is not protected by copyright. The trade, or brand, name is assigned by the manufacturer and is protected by copyright. To prevent confusion, the use of generic names rather than trade names is encouraged. Drugs also are classified by their use. For example, Advil is a brand name for the generic drug ibuprofen, which is classified as an analgesic and an anti-inflammatory agent. A pharmaceutical glossary could be a book in itself. Many terms are combinations of the condition to be treated plus the prefix anti- (e.g., antianginal, antianxiety, antiarrhythmic, anticoagulant, anticonvulsant, antidiarrheal). Notice how these names emphasize the drug’s effect (use) rather than its action in the body. More recent classifications, such as parasympathomimetic and cholinesterase inhibitor, describe the pharmacologic action rather than the therapeutic use. Both viewpoints are necessary for a more complete understanding of drugs and their action in the human body. No one can remember all there is to know about clinical pharmacology. The number of new drugs introduced into use far exceeds the number of older drugs replaced or discontinued. The number of drugs available for clinical use grows beyond the ability to learn all there is to know about each medication. Therefore, it is essential that a medical assistant understand how to use pharmacology resource books as references. Reference books that are updated annually or periodically should be available for easy reference at all medical facilities. Most references list drug information in the following sequence: 1. Action: How the drug provides therapeutic results in the body, or the use of the drug. 2. Indication: The conditions for which the drug is used. 3. Contraindications: Conditions that make administration of the drug improper or undesirable. 4. Precautions: Necessary actions that must be taken because of special conditions of the patient, the drug, or the environment; they need to be considered if the drug is to be successful or not harmful. The drug’s pregnancy risk category is included in this section, as are precautions for nursing mothers (Table 33-2). 6. Dosage and administration: Usual route, dosage, and timing for administering the drug. TABLE 33-2 Pregnancy Risk Drug Categories Every drug package contains an insert describing all the significant aspects of using the drug, including information on the chemical formulation of the drug and clinical studies. The information in the insert is controlled by the FDA and serves as an excellent quick reference on new medications in the ambulatory setting. The Physicians’ Desk Reference (PDR) is published annually by Thomson Medical Economics Company (Oradell, New Jersey). The PDR is provided free to physicians who subscribe to Medical Economics magazine. Copies can be purchased through the publisher or in local bookstores. Supplements are published quarterly throughout the year. The PDR contains information on approximately 2,500 drugs and includes product descriptions that are identical to the information provided in package inserts. The drug manufacturers pay for this space, so the PDR could be considered the Yellow Pages of the drug industry. The PDR is the most commonly used drug reference book and should be available in all healthcare facilities. The book’s sections are color-coded and cross-referenced for easy use. The various sections allow you to begin searching for information about a drug from any starting point. You can start with the usage, classification, generic name, manufacturer’s name, or trade name of a drug or what the drug looks like. A special photographic section enables visual identification of products. Once you know which drug you want to study, the product information section lists the actual package insert information alphabetically, first by the manufacturer, then by the brand name. A separate PDR volume, the Physicians’ Desk Reference for Nonprescription Drugs, is published annually for OTC drugs and dietary supplements. The six sections of the PDR are color-coded as follows: The U.S. Pharmacopeia/National Formulary (USP/NF) is the official source of drug standards for the United States. The Pharmacopeia was combined with the National Formulary, which lists the chemical formulas for all accepted drugs. This combined reference lists and describes all approved medications in the United States considered useful and therapeutic in the practice of medicine. Single drugs rather than combined products (compound mixtures) are listed. If a drug name is the same as the official name in this volume, the drug is followed by the initials USP (e.g., digitoxin, USP). The study of pharmacology is difficult at best. However, a few tips can help make it easier: Drugs are dispensed in two ways: over the counter and by prescription. OTC drugs are available to the public for self-medication without a prescription. These drugs have been approved by the FDA for general consumer use, but patients taking prescription drugs should keep their healthcare providers informed about their OTC drug use. A medical assistant directly involved in patient care should have an understanding of some basic facts about OTC drugs. Today patients are better informed about their personal healthcare, and many want to be active participants in healthcare decisions. They need facts to make informed choices when using OTC preparations. Most OTC preparations are safe if used as directed on the package; however, patient education contributes greatly to the safe and correct use of OTCs. Patients should be encouraged to do the following when choosing or using an OTC: • Carefully read the package label and insert for use guidelines. • Take only the recommended dose. • Monitor the expiration date and discard the medication when appropriate. • Never combine an OTC with a prescription drug without the physician’s knowledge. The number of prescription drugs that have been granted OTC status is constantly increasing, and as the list of OTC drugs increases, so does the need for consumer education. Many OTC medications influence the safety and effectiveness of prescription drugs; therefore, gathering information to discern a complete and accurate pattern of the patient’s use of OTC drugs should be part of every visit to the physician. Federal law makes drugs that are dangerous, powerful, or habit-forming illegal to use except under a physician’s order. A prescription is an order written by the physician for the dispensing of a particular medication by the pharmacist and its administration to the patient. Sometimes an order may be written by the physician on the patient’s medical record; however, most often it is an order written on a prescription blank for the pharmacist to fill (Figure 33-1). The prescription must be signed by the physician, or the order cannot be carried out (Procedure 33-1). If the physician requests that the medical assistant phone in a prescription to the pharmacy, all pertinent information for the medication order must be written down and reviewed by the physician for accuracy before the call is made. A note is made in the patient’s chart that a medication order was phoned into the pharmacy, with all of the pertinent information about the order included. Appropriate medical terminology and abbreviations must be used to complete the prescription. The more common terms and abbreviations are listed in Table 33-3. In an attempt to reduce the number of medication errors caused by incorrect use of medical terminology, the Joint Commission (formerly known as The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations [JCAHO]) recently developed a “Do Not Use” list of abbreviations, acronyms, and symbols that should not be used for documentation purposes in accredited institutions. The Joint Commission also created an ancillary list of possible future inclusions. Both of these lists are presented in Table 33-4. In addition to the Joint Commission lists, facilities have the option of creating their own list of problematic abbreviations that employees should avoid using. TABLE 33-3 Common Prescription Abbreviations

Principles of Pharmacology

Learning Objectives

Vocabulary

Scenario

Government Regulation

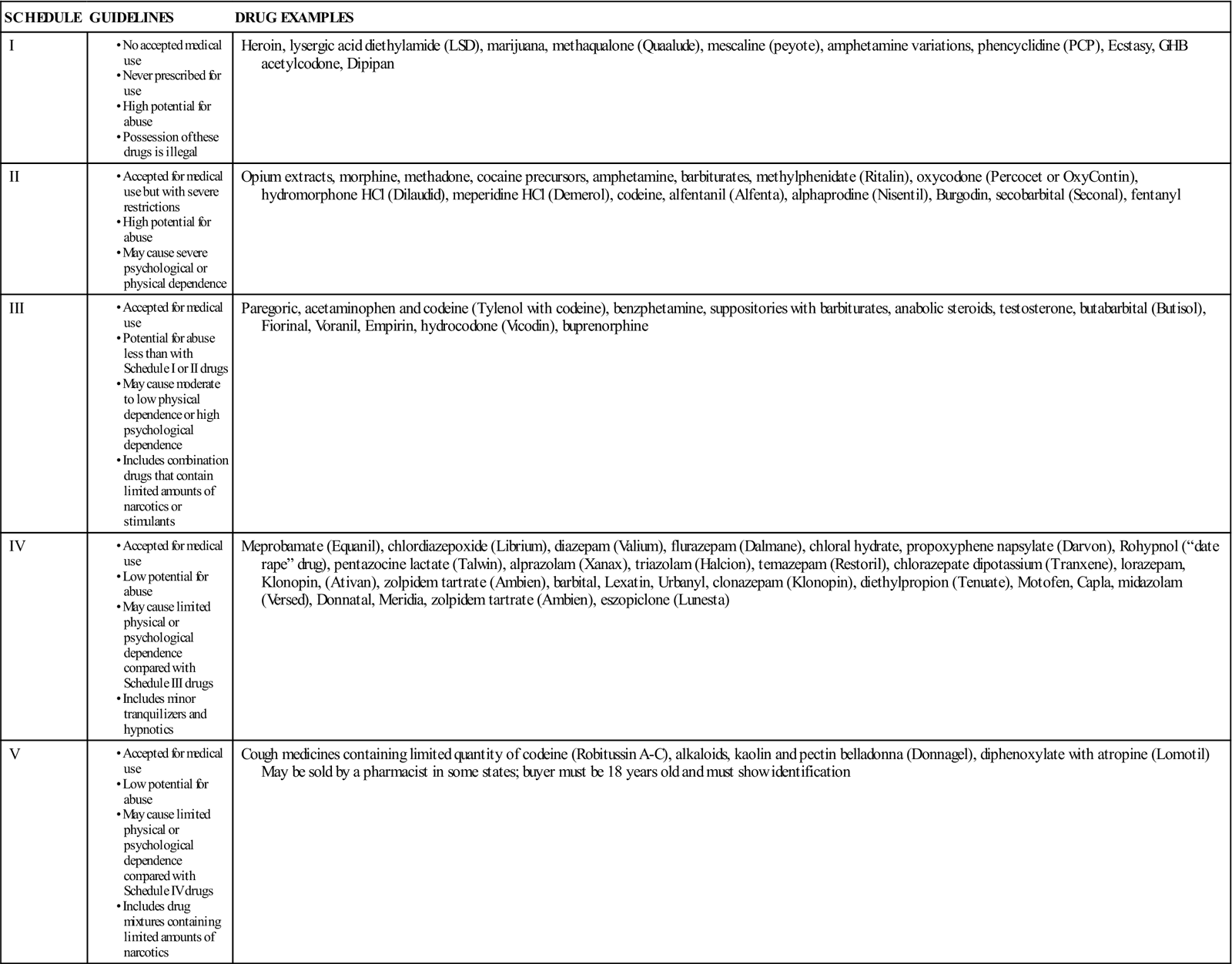

Controlled Substances

Regulation of Controlled Substances

Drug Abuse

Drug Names

Approaches to Studying Pharmacology

Drug Reference Materials

DRUG CATEGORY

RISK/DESCRIPTION

A

Remote risk.

Controlled studies in women have failed to demonstrate risk to fetus.

B

Slightly more risk than A.

Animal studies show no risk, but controlled human studies have not been done; or animal studies show risk, but controlled studies in women have shown no risk.

C

Greater risk than B.

Animal studies have shown risk, but no controlled human studies have been done; or no studies have been done in animals or women.

D

Proven risk of fetal harm.

Human studies show proof of fetal damage, but the potential benefits of use during pregnancy may make its use acceptable.

X

Proven risk of fetal harm.

Studies in women or animals show definite risk of fetal abnormality. Risks outweigh any possible benefit.

Package Inserts

Physicians’ Desk Reference

U.S. Pharmacopeia/National Formulary

Learning About Drugs

Dispensing Drugs

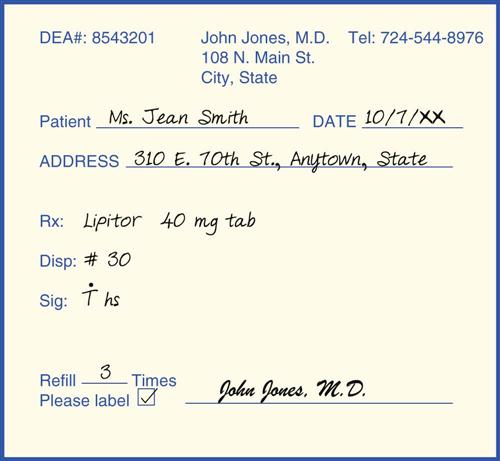

Prescription Drugs

ABBREVIATION

MEANING

ABBREVIATION

MEANING

ABBREVIATION

MEANING

aa

of each

ID

intradermal

pt

patient

ac

before meals

IM

intramuscular

pt

pint

ad lib

as desired

IV

intravenous

pulv

powder

agit

shake, stir

K

potassium

qh

every hour

am

morning

kg

kilogram

q2h

every 2 hours

amp

ampule

KVO

keep vein open

q3h

every 3 hours

AD

right ear

L

liter

q4h

every 4 hours

AS

left ear

lb

pound

qid

four times a day

ASA

aspirin

LR

lactated Ringer’s solution

qm

every morning

AU

both ears

minim

qn

every night

aq

water

mcg

microgram

qod

every other day

bid

twice a day

med

medicine

qs

quantity sufficient

C

cup, Celsius

meq

milliequivalent

qt

quart

with

mg

milligram

R

rectal

cap

capsule

mL

milliliter

Rx

take, treatment

CC

chief complaint

MLD

minimum lethal dose

r/o

rule out

cc

cubic centimeter

mn

midnight

S, Sig

give the following directions

cm

centimeter

MO

mineral oil

or w/o

or w/o

without

c/o

complaining of

MOM

milk of magnesia

SC, SQ, subQ

subcutaneous

D/C

discharge

MS

morphine sulfate

SOB

shortness of breath

Dx

diagnosis

MTD

maximum tolerated dose

one-half

dil

dilute

NKA

no known allergies

stat

immediately

disp

dispense

noct

at night

sub-q

subcutaneous

dr

dram

NPO

nothing by mouth

T, tbs

tablespoon

EENT

eye, ear, nose, throat

NS

normal saline

t, tsp

teaspoon

ext

extract

N/V

nausea/vomiting

TAB

tablet

F

Fahrenheit

O2

oxygen

tid

three times a day

FDA

Food and Drug Administration

OD

overdose

tinct

tincture

FE

iron

OD

right eye

TO

telephone order

fl

fluid

OS

left eye

tus

cough

fx

fracture

OU

both eyes

ung

ointment

gal

gallon

OTC

over-the-counter (drugs)

vag

vagina

gm, g

gram

oz

ounce

ves

bladder

gr

grain

pc

after meals

VO

verbal order

gtt

drops

PL

placebo

VS

vital signs

h

hour

pm

afternoon

W/O

water in oil

hs

at bedtime

PMI

patient medication instruction

WNL

within normal limits

HTN

hypertension

po

by mouth

x

times

Hx

history

pr

per rectum

y/o

years old

inj

injection

prn

as needed

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Principles of Pharmacology

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

tab po hs.

tab po hs.