Sharon Baranoski, MSN, RN, CWCN, APN-CCRN, MAPWCA, FAAN

Janet E. Cuddigan, PhD, RN, CWCN, FAAN

Wendy S. Harris, RN, BSHS, BSN

The contributions of Courtney H. Lyder, ND, GNP, FAAN in previous editions is gratefully acknowledged.

Objectives

After completing this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- discuss the significance of pressure ulcers as a healthcare problem

- explain the etiology of a pressure ulcer

- describe how to complete a risk assessment tool

- discuss strategies for pressure ulcer prevention

- define pressure ulcer classification systems

- discuss strategies for treating a patient with pressure ulcers

- state how to determine pressure ulcer prevalence and incidence.

Pressure Ulcers as a Healthcare Problem

Pressure ulcers are a global healthcare concern and require an interdisciplinary approach to care and management.1,2 All clinicians need to be responsible for the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers.

Over the centuries, pressure ulcers have been referred to as decubitus ulcers, bedsores, and pressure sores. The term pressure ulcer has become the preferred name because it most closely describes the etiology and resultant ulcer. The 2014 pressure ulcer clinical guideline written by the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP), European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP), and the Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance (PPPIA) released this common definition: “A pressure ulcer is a localized injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue usually over a bony prominence, as a result of pressure, or pressure in combination with shear. A number of contributing or confounding factors are also associated with pressure ulcers; the significance of these factors is yet to be elucidated.” Pressure ulcers are usually located over bony prominences (such as the sacrum, coccyx, hips, heels) and are classified according to the extent of the type of observable tissue damage.1 Relying just on depth of tissue damage rather than tissue type may be misleading because pressure ulcers in locations where there is little adipose tissue, such as the ear, may be shallow but still extend through the subcutaneous tissue1 (Box 13-1).

Box 13-1 International NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA Pressure Ulcer Classification System

Category/Stage I: Nonblanchable Erythema

© J. M. Levine, MD

- Intact skin with nonblanchable redness of a localized area, usually over a bony prominence. Darkly pigmented skin may not have visible blanching; its color may differ from the surrounding area.

- The area may be painful, firm, soft, warmer, or cooler as compared to adjacent tissue. Category/Stage I may be difficult to detect in individuals with dark skin tones. May indicate “at-risk” persons (a heralding sign of risk).

Category/Stage II: Partial-Thickness Skin Loss

© H. Brem, MD

- Partial-thickness loss of dermis presenting as a shallow open ulcer with a red-pink wound bed, without slough. May also present as an intact or open/ruptured serum-filled blister. Presents as a shiny or dry shallow ulcer without slough or bruising.* This Category/Stage should not be used to describe skin tears, tape burns, perineal dermatitis, maceration, or excoriation.

Category/Stage III: Full-Thickness Skin Loss

© H. Brem, MD

- Full-thickness tissue loss. Subcutaneous fat may be visible, but bone, tendon, or muscle are not exposed. Slough may be present but does not obscure the depth of tissue loss. May include undermining and tunneling.

- The depth of Category/Stage III pressure ulcer varies by anatomical location. The bridge of the nose, ear, occiput, and malleolus do not have subcutaneous tissue, and Category/Stage III ulcers can be shallow. In contrast, areas of significant adiposity can develop extremely deep Category/Stage III pressure ulcers. Bone/tendon is not visible or directly palpable.

Category/Stage IV: Full-Thickness Tissue Loss

© H. Brem, MD

- Full-thickness tissue loss with exposed bone, tendon, or muscle. Slough or eschar may be present on some parts of the wound bed. Often includes undermining and tunneling.

- The depth of a Category/Stage IV pressure ulcer varies by anatomical location. The bridge of the nose, ear, occiput, and malleolus do not have subcutaneous tissue, and these ulcers can be shallow. Category/stage IV ulcers can extend into muscle and/or supporting structures (e.g., fascia, tendon, or joint capsule), making osteomyelitis possible. Exposed bone/tendon is visible or directly palpable.

Unstageable: Depth Unknown

© Elizabeth A. Ayello

- Full-thickness tissue loss in which the base of the ulcer is covered by slough (yellow, tan, gray, green, or brown) and/or eschar (tan, brown, or black) in the wound bed.

- Until enough slough and/or eschar is removed to expose the base of the wound, the true depth, and therefore Category/Stage, cannot be determined. Stable (dry, adherent, intact without erythema or fluctuance) eschar on the heels serves as “the body’s natural (biological) cover” and should not be removed.

Suspected Deep Tissue Injury: Depth Unknown

© J. M. Levine, MD

- Purple or maroon localized area of discolored intact skin or blood-filled blister due to damage of underlying soft tissue from pressure and/or shear. The area may be preceded by tissue that is painful, firm, mushy, boggy, or warmer or cooler as compared to adjacent tissue.

- Deep tissue injury may be difficult to detect in individuals with dark skin tones. Evolution may include a thin blister over a dark wound bed. The wound may further evolve and become covered by thin eschar. Evolution may be rapid, exposing additional layers of tissue even with optimal treatment.

*Bruising indicates suspected deep tissue injury.

From Haesler, E, ed., National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP), European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP), Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance (PPPIA). Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Clinical Practice Guideline. Perth, Australia: Cambridge Media, 2014:40–41. Used with permission.

The incidence and prevalence of pressure ulcers are truly enigmatic. Pressure ulcers aren’t a reportable event in all healthcare settings, so data are speculative at best. We do know, however, that the numbers are significant enough to warrant national healthcare initiatives in the United States as well as other countries. As early as 1989, the US federal government focused its attention on pressure ulcers with the appointment of a panel charged with developing the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) guidelines.3,4 Since that time, clinical practice guidelines regarding pressure ulcers have been released by several other organizations, including the Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society (WOCN),5 the Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO),6 the Wound Healing Society (WHS),7 the American Medical Directors Association (AMDA),8 and the Association for the Advancement of Wound Care (AAWC).9

Long-term care in the United States has long been regulated regarding pressure ulcers as mandated by Federal Tag (F-Tag) 314.10 In addition, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ; formerly AHCPR) stated in its 2008 statistical brief report that there was nearly an 80% increase in hospital stays in which pressure ulcers were noted, even though the total number of hospitalizations for the reported time period (1993–2006) increased by only 15%.11 Given the attention from regulatory and quality improvement agencies on pressure ulcer occurrence, preventing pressure ulcers should be a priority of patient care across all care settings.

The financial costs associated with pressure ulcers to all institutions and facilities aren’t precisely known. According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the average cost of pressure ulcers for hospitalized patients in 2007 was $43,180.11 Published estimates of treatment costs vary across hospitals, long-term care, and home care settings; the one certainty is that pressure ulcers do create a financial burden for the facility, patient, and family alike. Pressure ulcers cost institutions valuable staff time, supplies, and reputation.

Pressure ulcer practices should be evidence based. However, adequate research-based, randomized clinical studies to support all of our current practices do not exist. For example, in the NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA clinical practice guideline, there are 575 recommendations, where the strength of the evidence for each recommendation is ranked with a letter based on the type of studies. Recommendations given an A are “supported by direct scientific evidence from properly designed and implemented controlled trials on pressure ulcers in humans (or humans at risk for pressure ulcers), providing statistical results that consistently support the recommendations (level 1 studies required).”1 In the NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA clinical practice guideline, there are six recommendations at the A level of strength of evidence (Box 13-2).1 Wound care interventions and modalities have often been based on an “it works for me” attitude. New to the NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA clinical guideline is an indication of the strength of each recommendation. Based on consensus voting by the experts who developed the guideline, a system using thumbs up or thumbs down is given to indicate how confident a healthcare professional can be that the recommendation will improve patient outcomes.1 There are five different possibilities of strength of recommendation to help prioritize interventions. For example, one thumb up ( ) means a weak positive recommendation; probably do it, while two thumbs up (

) means a weak positive recommendation; probably do it, while two thumbs up (

) means a strong positive recommendation; definitely do it.1 We need to encourage healthcare providers to participate in research studies so that we’ll have more evidence in the future to direct and improve our clinical decision-making process, thereby improving patient outcomes.

) means a strong positive recommendation; definitely do it.1 We need to encourage healthcare providers to participate in research studies so that we’ll have more evidence in the future to direct and improve our clinical decision-making process, thereby improving patient outcomes.

Box 13-2 NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendations at Strength of Evidence = A

- Offer high-calorie, high-protein nutritional supplements in addition to the usual diet to adults with nutritional risk and pressure ulcer risk, if nutritional requirements cannot be achieved by dietary intake. (Strength of Evidence = A; Strength of Recommendation =

)

)

- Reposition all individuals at risk of or with existing pressure ulcers, unless contraindicated (Strength of Evidence =A; Strength of Recommendation =

)

)

- Consider the pressure redistribution support surface in use when determining the frequency of repositioning. (Strength of Evidence = A; Strength of Recommendation =

)

)

- Use a high-specification reactive foam mattress rather than a non–high-specification reactive foam mattress for all individuals assessed as being at risk for pressure ulcer development. (Strength of Evidence = A; Strength of Recommendation =

)

)

- Consider the use of direct contact (capacitive) electrical stimulation to facilitate wound healing in recalcitrant Category/Stage II pressure ulcers as well as any Category/Stage III and IV pressure ulcers. (Strength of Evidence = A; Strength of Recommendation =

)

)

- Regularly reposition the older adult who is unable to reposition independently. There is no evidence of the superiority of one higher-specification foam mattress over an alternative higher-specification foam mattress. (Strength of Evidence = A; Strength of Recommendation =

)

)

Haesler E, ed. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and Pan Pacific Pressure Ulcer Injury Alliance. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Clinical Practice Guideline. Perth, Australia: Cambridge Media 2014. Used with permission.

Wound Etiology

How do pressure ulcers occur? This is an interesting and challenging question. Literature reviews demonstrate several etiologies of pressure ulcers. Earlier reviews focused on a model of pressure ulcer development caused by pressure-induced capillary closure cutting off blood supply leading to tissue ischemia, injury, and death. More recent research, using techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), has documented cellular distortion and damage from pressure due to mechanical loading and deformation of soft tissues near bony prominences.1 There is also a renewed appreciation for the effects of shear in damaging deeper tissue and the emerging role that microclimate (moisture and temperature) in rendering tissue less tolerant of the effects of pressure might affect.1,12

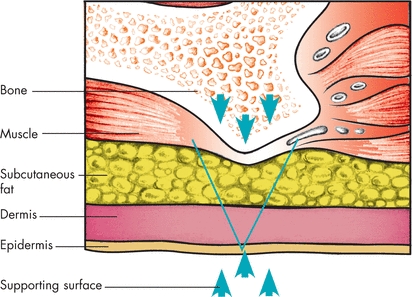

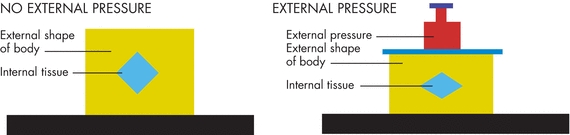

The recent international NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA clinical practice guideline states that “pressure ulcers develop as a result of the internal response to external mechanical load.”1 Simply stated, it is how a person’s soft tissue responds to sustained pressure (mechanical loading). The latest explanation from the NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA1 as to the etiology of pressure ulcers involves the interplay of mechanical loading and an individual’s tissue tolerance. Mechanical load is a complex process that research is still contributing to our understanding. How mechanical loading affects tissues varies and depends on several characteristics including tissue size, shape, stiffness, strength, and diffusion properties as well as the magnitude and length of time that mechanical loading is applied to the tissue.1 The pressure gradient1,4,13–16 has been used to explain how pressure translates into tissue death (Fig. 13-1). External pressure is transmitted from the epidermis inward toward the bone as well as by counter-pressure from the bone. As a result, the loaded soft tissues, including skin and deeper tissues (adipose tissue, connective tissue, and muscle), will deform, resulting in strain and stress within the tissues.1

Figure 13-1. Pressure gradient. In this illustration, the V-shaped pressure gradient results from the upward force (upward arrowheads) exerted by the supporting surface against downward force (downward arrowheads) exerted by the bony prominence. Pressure is greatest on tissues at the apex of the gradient and lessens to the right and left of this point.

Practice Point

Practice Point

Muscle tissue dies first from pressure. Look at a variety of extrinsic and intrinsic factors that could put your patient at risk for pressure ulcers.

Body tissues differ in their ability to tolerate pressure. The blood supply to the skin originates in the underlying muscle. Muscle is more sensitive to pressure damage than skin tissue.1 Tissue tolerance is further compromised by extrinsic and intrinsic factors. Extrinsic factors that are gaining momentum as to the role they may play in pressure ulcer development include moisture, and temperature, and are usually collectively referred to as microclimate.1 NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA1 suggests that microclimate plays a role in the development of Category/Stage I and II pressure ulcers. They also suggest that another intrinsic factor, tissue perfusion (or lack thereof), and the resulting ischemia may be another important part of explaining how pressure ulcers occur.1 A 2013 comprehensive systematic review of risk factor research by Coleman and colleagues helps explain the complex interaction between increased pressure intensity/duration and the extrinsic and intrinsic factors that affect tissue tolerance to pressure.1,17 Based on their review of 54 studies of 34,449 patients in both acute care and the community, they identified three primary independent predictors for pressure ulcer development: mobility/activity, perfusion (including diabetes), and skin/pressure ulcer status.17 Activity and mobility limitations create the necessary conditions for pressure ulcers to develop (i.e., unrelieved pressure). Individuals who are bedbound, chairfast, and unable to effectively reposition themselves fall into these risk factor categories and should be considered at risk. Epidemiological studies show that limitations in activity and mobility are independently predictive of pressure ulcers. Changes in sensory perception may further impair movement.

Once the conditions for increased pressure intensity and duration are established, intrinsic and extrinsic factors affecting tissue tolerance contribute to pressure ulcer development. According to epidemiological evidence, these factors fall under several categories, which include factors affecting perfusion and oxygenation (e.g., hypotension, hemodynamic instability, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, vasopressor drugs, need for supplemental oxygen); poor nutritional status (e.g., decreased intake of nutrients—especially protein, weight loss, low albumin); and skin moisture (e.g., urinary or fecal incontinence, excessive sweating, or wound drainage).1 There is less evidence to support the following advanced age, friction, immunity, poor general health status, and increased body temperature.1

Shear has the potential to damage deeper tissue. Shear and friction are two separate phenomena, yet they often work together to create tissue ischemia and ulcer development.

Friction is a force that is parallel to the skin surface and may damage the epidermis causing blisters but not pressure ulcers.1 The tissue injury resulting from friction may look like a superficial skin insult.

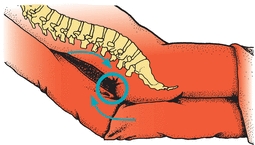

Shear (shear stress) is “the force per unit area exerted parallel to the plane of interest”1 while shear strain is the “distortion or deformation of tissue as a result of shear stress.”1 You can think of shear stress and strain as pulling the bones of the pelvis in one direction and the skin in the opposite direction (Figs. 13-2 and 13-3). The deeper fascia slides downward with the bone, while the superficial fascia remains attached to the dermis. This insult and compromise to the blood supply create ischemia, reperfusion injury, lymphatic impairment, and mechanical deformation of tissue cell18,19 and lead to cellular death and tissue necrosis. Shear and friction go hand in hand—you’ll rarely see one without the other.

Figure 13-2. Shearing force. Shear injury is a mechanical force parallel, rather than perpendicular, to an area of tissue. In this illustration, gravity pulls the body down the incline of the bed. The skeleton and attached deep fascia slide within the skin, while the skin and superficial fascia, attached to the dermis, remain stationary, held in place by friction between the skin and the bed linen. This internal slide compromises blood supply to the area and deforms or distorts tissue.

Figure 13-3. Effects of shear on tissue. ©2006, C.W.J. Oomens. Used with permission.

Practice Point

Practice Point

You won’t see shear injury initially at the skin level because it occurs underneath the skin. You will see friction injury. Elevation of the head of the bed increases shear injury in the deep tissue and may account for the number of sacral ulcers we see in practice.

Exactly what causes pressure ulcers remains controversial.20 Theories on the etiology of pressure ulcers need continued research.

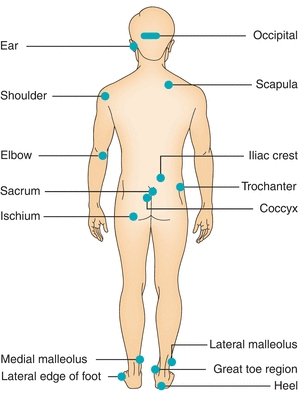

Most pressure ulcers occur in the lower part of the body over bony prominences such as the sacrum, coccyx, ischial tuberosities, greater trochanters, heels, iliac crests, and lateral and medial malleoli13,21 (Fig. 13-4). Other areas, where pressure ulcers may be overlooked, include the occiput (especially in infants and toddlers; see Chapter 22, Pressure ulcers in neonatal and pediatric populations), elbows, scapulae, and ears (especially in patients using nasal oxygen cannulas).

Figure 13-4. Pressure ulcer sites. Shown in this illustration are the most common sites where pressure ulcers develop.

Several national surveys demonstrated that the most common site for pressure ulcers among patients in acute care facilities is the sacrum, with the heels being second.21 The incidence of heel ulcers has increased incrementally over the past decade, creating a need for prevention protocols targeting the heels. The HEELS© mnemonic22 can be used to care for heels at risk for pressure ulcers (Box 13-3). A growing clinical problem is pressure ulcers caused by medical devices (Fig. 13-5). In a survey of 86,932 patients in acute care facilities, 9.1% of all pressure ulcers identified were device related, with the ear being the most common site (20%).21 Devices that are commonly associated with pressure ulcers include respiratory devices such as oxygen tubing (ears), nasotracheal tubes (ET, mouth and lips), continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) masks, and biphasic positive airway pressure (Bi-PAP) (bridge of nose, face); orthopedic devices including cervical collars (neck and head), halo devices, external fixators, plaster casts; and other medical devices such as splints, braces, urinary catheters, fecal containment devices, venous or dialysis catheters, heel suspension devices, thromboembolic deterrent hose, restraints, graduated compression stockings, and intermittent pneumatic compression device sleeves (lower extremities).1 Any tube under pressure can create pressure damage. Edematous patients are at particularly high risk.23 Pressure ulcers on the mucosa from medical devices are not staged using the NPUAP International Pressure Ulcer Classification System. A position paper and helpful posters to use to educate clinicians about mucosal pressure ulcers can be found on the NPUAP Web site.24

Figure 13-5. Medical device injury. © J. M. Levine, MD

Box 13-3 HEELS © Mnemonic

Have foot or leg movement?

Evaluate heels and sensation.

Evaluate foot drop risk.

Limit friction.

Suspend heels with devices as needed.

Used with permission from Cuddigan, J., Ayello, E.A., Black, J. “Saving Heels in Critically Ill Patients,” World Council of Enterostomal Therapists Journal 28(2):16–24, 2008. Copyright © 2005, Ayello, Cuddigan, and Black.

Practice Point

Practice Point

Careful observation of the sacrum/coccyx and heels is warranted because these are the most frequent sites of pressure ulcers.

Prevention

Preventing pressure ulcers is of vital importance. Elements of pressure ulcer prevention include identifying individuals at risk for developing pressure ulcers, preserving skin integrity, treating the underlying causes of the ulcer, relieving pressure, paying attention to the total state of the patient to correct any deficiencies, and educating the patient and his or her family about pressure ulcers.

Risk Factors and Risk Assessment

Risk assessment is used to identify patients at risk and the type of risk. Identifying individuals at risk for pressure ulcers enables clinicians to make decisions about when to begin using preventive measures. This is important for the most effective use of resources because the type of risk guides the intensity and cost of preventive interventions. Risk assessment is governed by the regulations in effect in a particular setting. For example, the Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS-C) guidelines for home care recommend that a structured approach to risk assessment be conducted on all home care clients.25,26 MDS 3.0 describes several methods for determining a long-term care resident’s pressure ulcer risk, which may include a formal assessment instrument, a clinical assessment conducted by the clinician of the skin, comorbidities, health and functional status, an existing stage 1 or higher pressure ulcer, a scar over a bony prominence, or a nonremovable dressing or device.27–29 The NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA guideline considers adults that have a medical device to be at risk for pressure ulcers based on a B strength of evidence and a two thumbs up strength of recommendation for this practice.1 They recommend that the skin under or around a medical device(s) should be inspected at least twice daily for signs of pressure-related injury.1

Risk assessment is a comprehensive process that some clinicians in the past thought only included use of the many validated pressure ulcer risk assessment tools that are available, including the Norton Scale,30 the Gosnell Scale,31 the Braden Scale,32 and the Waterlow Scale.33 The NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA clinical guideline emphasizes that these risk assessment tools are only part of a systematic and complete assessment for pressure ulcer risk.1 Deciding which scale to use can be challenging. Reviewing the reliability (consistency) and validity (accuracy) of each scale should always be the first step in the decision-making process. Reliability for risk assessment scales is usually described in terms of interrater reliability. According to Ayello and Braden,34 “a common measure of inter-rater reliability for a risk assessment tool is percentage agreement, which looks at the percentage of instances in which different raters assign the same score to the same patients. Validity, or accuracy, is measured by the ability of the tool to correctly predict who will or won’t develop a pressure ulcer.” There are several risk assessment tools used to identify those at high risk. Chou and colleagues identified over 747 full text articles and, based on 120 studies, eventually included in their review that while there was no difference among the instruments in diagnostic accuracy, the Braden, Norton, and Waterlow Scales did identify patients at increased risk but were weak predictors.35 Furthermore, they urged more research to better understand how these tools compared with clinical judgment regarding pressure ulcer incidence. A 2014 meta-analysis by Garcia-Fernandez and colleagues of risk assessment tools has provided new insights regarding risk assessment tools.36

Predictive validity is dependent on the sensitivity and specificity of the tool. Sensitivity is “the percentage of individuals who develop a pressure ulcer who were assessed as being at risk for a pressure ulcer. A tool has good sensitivity if it correctly identifies true positives while minimizing false negatives. Specificity is the percentage of individuals who don’t develop a pressure ulcer who were assessed as being not at risk for developing an ulcer. A tool has good specificity if it identifies true negatives and minimizes false positives.”34,37 Because of the amount of clinical research supporting their reliability and validity, the Norton,30 Braden,23 and Waterlow33 Scales are primarily used in clinical practice to determine pressure ulcer risk assessment.

Braden Scale

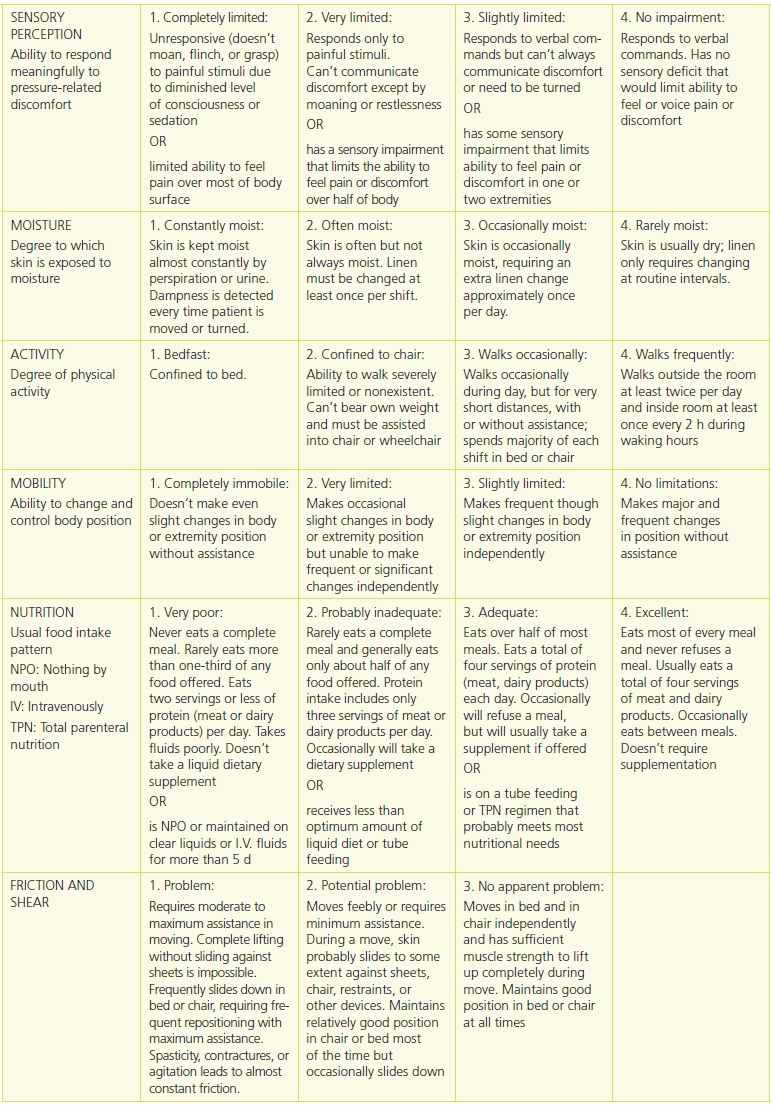

The Braden Scale is the most commonly used pressure ulcer assessment tool in the United States. Available in many languages (English, French, Portuguese)38–40 and used worldwide, this copyrighted tool was created in 1987 by Barbara Braden and Nancy Bergstrom32 and is available at http://www.bradenscale.com/images/bradenscale.pdf.38 The Braden Scale has six subscales: sensory perception, moisture, activity, mobility, nutrition, and friction/shear32,34,37 (Table 13-1). The scale is based on the two primary etiologic factors of pressure ulcer development—intensity and duration of pressure and tissue tolerance for pressure. “Sensory perception, mobility, and activity address clinical situations that predispose a patient to intense and prolonged pressure, while moisture, nutrition, and friction/shear address clinical situations that alter tissue tolerance for pressure.”34

Table 13-1 Braden Scale: Predicting Pressure Ulcer Risk

Used with permission from Barbara Braden, PhD, RN, FAAN, and Nancy Bergstrom, PhD, RN, FAAN. © 1988.

Each subscale contains a numerical range of scores, with 1 being the lowest score possible.32 The sensory perception, moisture, activity, mobility, and nutrition subscales have scores ranging from 1 to 4. Friction/shear is the only subscale in which scores range from 1 to 3. Definitions of each subscale as to what patient characteristics to evaluate are given for each numerical ranking. While in the past emphasis was on the overall Braden Scale score, which was derived from totaling the numerical ratings from each of the six subscales, the 2014 NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA clinical guideline now recommends that the subscale scores and other patient risk factors not captured on risk assessment scales should be included as part of an individualized pressure ulcer prevention plan of care.1

Both the CMS27 and the NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA clinical guideline1 stress the importance of using a systematic process for determining pressure ulcer risk that may include clinical judgment, skin assessment, and review of risk factors not part of validated pressure ulcer risk assessment tools and not just relying on interpreting the total Braden Scale score because not all risk factors are quantified on the scale (low subscale scores need to be considered). The systematic review of patient risk factors for pressure ulcer development by Coleman and colleagues17 also underscores the importance of a comprehensive risk assessment when they state “overall there is no single factor which can explain pressure ulcer risk, rather a complex interplay of factors which increase the probability of pressure ulcer development.”

Determining all factors that place an individual at risk for a pressure ulcer is helpful when deciding on appropriate prevention strategies. Once a person is determined to be at risk for a pressure ulcer, preventive protocols based on the individualized assessment need to be implemented. Recommendations for pressure ulcer prevention management by level of risk are available on the Braden Web site.39 However, as the NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA has emphasized in the 2014 clinical guideline,1 the individualized plan of care for any particular patient needs to be based on his or her specific risk factors and needs.

Questions have surfaced regarding when to assess patients for pressure ulcer risk and when to reassess risk. These two aspects of care are both very important. The NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA clinical practice guideline recommends that initial pressure ulcer risk be assessed as soon as possible after admission (within 8 hours).1 Reassessment interval should be based on the person’s acuity and if there is any change in the patient’s condition1 (Box 13-4). Studies by Bergstrom and Braden40,41 found that in skilled nursing facilities, 80% of pressure ulcers develop within 2 weeks of admission and 96% develop within 3 weeks of admission.

Box 13-4 Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment Recommendations

General Recommendations for Structured Risk Assessment

1. Conduct a structured risk assessment as soon as possible (but within a maximum of 8 hours after admission to identify individuals at risk of developing pressure ulcers). (Strength of Evidence = C; Strength of Recommendation =  )

)

2. Repeat the risk assessment as often as required by the individual’s acuity. (Strength of Evidence = C; Strength of Recommendation =  )

)

3. Undertake a reassessment if there is any significant change in the individual’s condition. (Strength of Evidence = C; Strength of Recommendation =

)

)

4. Include a comprehensive skin assessment as part of every risk assessment to evaluate any alterations to intact skin. (Strength of Evidence = C; Strength of Recommendation =

)

)

5. Document all risk assessments. (Strength of Evidence = C; Strength of Recommendation =

)

)

6. Develop and implement a risk-based prevention plan for individuals identified as being at risk of developing pressure ulcers. (Strength of Evidence = C; Strength of Recommendation =

)

)

Caution: Do not rely on a total risk assessment tool score alone as a basis for risk-based prevention. Risk assessment tool subscale scores and other risk factors should also be examined to guide risk-based planning.

Structured Risk Assessment

1. Use a structured approach to risk assessment that is refined through the use of clinical judgment and informed by knowledge of relevant risk factors. (Strength of Evidence = C; Strength of Recommendation =

)

)

Risk Factor Assessment

1. Use a structured approach to risk assessment that includes assessment of activity/mobility and skin status. (Strength of Evidence = B; Strength of Recommendation =

)

)

Activity and Mobility Limitations

1. Consider bedfast and/or chairfast individuals to be at risk of pressure ulcer development. (Strength of Evidence = B; Strength of Recommendation =

)

)

2. Consider the impact of mobility limitations of pressure ulcer risk. (Strength of Evidence = B; Strength of Recommendation =

)

)

Haesler E, ed. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and Pan Pacific Pressure Ulcer Injury Alliance. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Clinical Practice Guideline. Perth, Australia: Cambridge Media 2014. Used with permission.

Risk Assessment Acute Care

In the United States, there is no CMS-mandated frequency of risk assessment for acute care hospitalized patients. The WOCN guidelines5 recommend reassessment on a regularly scheduled basis or when there is a significant change in the individual’s condition such as surgery or decline in health status. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) recommends that pressure ulcer risk assessment be done every 24 hours.42 The World Union of Wound Healing Societies43 recommends that assessments be performed daily in the intensive care unit and every 2nd day on general medical/surgical floors.

Risk Assessment LONG-TERM CARE

Assess initially upon admission, then reassess weekly for the first 4 weeks, monthly to quarterly after that, and whenever the resident’s condition changes.40 Pressure ulcer risk assessment is now required under MDS 3.0 section M, Skin Conditions.27–29 Under section M0 100 of the MDS tool, the clinician can use any of the following criteria to determine risk:

- M0100A: Stage I or higher ulcer, scar over a bony prominence, or nonremoval dressing or device in place27–29

- M0100B: Formal assessment instrument or tool (i.e., Braden, Norton, or others)27–29

- M0100C: Comprehensive clinical assessment of the resident since this will include factors other than what is on formal tools27–29

Based on the determination of pressure ulcer risk by some methods in section M0100, in M0150, the clinician must check Yes or No to indicate whether the resident is at risk for developing pressure ulcers.27–29 Further details about MDS 3.0 section M skin conditions can be found on the CMS Web site27 or in the literature.28,29

Risk Assessment HOME HEALTH CARE

The plan of care needs to address the areas of risk for home care patients. A Braden Scale for the home care setting is available online39 and in the literature.32 Risk assessment tools complement clinical judgment, as patients with the same risk score may have differing actual risks. Section M1300, Pressure Ulcer Assessment of OASIS-C, identifies whether the home health agency providers assessed the patient’s risk of developing pressure ulcers by either evaluation of clinical factors or use of a standardized tool. CMS does not require the use of standardized tools, nor does it endorse one particular tool.25,26 Section M1302 addresses the question of whether the patient is at risk for developing pressure ulcers, with the answer being either No or Yes. Reassessment of risk should be performed with each home visit by a nurse.

Practice Point

Practice Point

CMS requires a pressure ulcer risk assessment in both long-term and home care settings. It does not mandate the use of a standardized risk tool (e.g., Braden, Norton).25–27

Patient Care to Prevent Pressure Ulcers

Preventing pressure ulcers can best be accomplished by using a multidisciplinary approach. Several pressure ulcer prevention protocols and guidelines exist,1,2,4–9,44–47 most of which advocate taking a holistic approach to pressure ulcer prevention. This includes processes on both the healthcare organizational level and the healthcare provider level that outline an evidence-based plan of care.1 The healthcare organization should have in place a systematic structure for monitoring and managing pressure ulcer care practices and incidence rates. Quality indicators should be developed and monitored to determine future improvements in care processes needed at the organizational level.1 Any good prevention program for the practitioner begins with assessing the patient’s skin. The skin should be assessed and its condition documented daily in acute- and long-term care settings and at each home care visit. Careful attention to preventing skin injury during performance of activities of daily living is paramount. The bathing schedule should be individualized based on the patient’s age, skin texture, and dryness or excessive oiliness of the skin. Use of nondrying products to clean the skin is recommended. One study found that the incidence of stage I and II pressure ulcers could be reduced by educating the staff about using body wash and skin protectant products.48 In another study by Carr and Benoit, the incidence of pressure ulcers decreased from 7.14% at baseline to 0% at the end of the study through education of nonlicensed staff about the use of protective skin barriers and implementation of a comprehensive interventional patient hygiene bathing and incontinence management program.49 Avoid excessive friction and hot water when cleaning. Use nonalcoholic moisturizers after bathing. A daily bath may not be needed for all patients; elderly patients, for example, may benefit from “lotion” baths.

For the incontinent patient, moisture barrier products such as creams and ointments should be considered as treatment options. Soiled skin should be cleaned immediately and products to protect the skin applied. If containment products are used, follow the correct methods of application. Reasons for incontinence should always be determined and appropriate measures to address the cause of the incontinence should be implemented.

Vulnerable skin should be protected from injury. Citing a B strength of evidence, the NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA recommends considering the prophylactic use of polyurethane foam dressing on the heel, sacrum, or other at risk locations to prevent pressure ulcers.1 In a study of 93 high-risk patients in a surgical trauma intensive care unit, the use of intervention bundles that included a prophylactic soft silicone dressing product resulted in zero pressure ulcers.50 Other authors have found similar results when various types of polyurethane foam or other foam dressings were used on critically ill patients and advocate their use in pressure ulcer prevention.51–67

Although a review of the literature suggests that one type of massage may be beneficial for at-risk patients,68 most clinical guidelines recommend against massaging reddened bony prominences because this can lead to further tissue damage.1,2,4 Keep the patient’s heels off the bed69; use pillows, wedges, and foot elevation devices as indicated (Box 13-2). Flex the knee when elevating the leg to avoid pressure injury to the Achilles tendon.1 Best practices for preventing heel pressure ulcers in orthopedic population are published.70

Practice Point

Practice Point

Keep the patient’s heels off the mattress!

Be careful not to drag your patient during transfers or position changes. Use appropriate devices, such as a turn sheet or mechanical lifting device, to prevent friction injuries to the patient’s skin. Use the 30-degree lateral position for patients in bed. Keep the head of the bed below 30 degrees to prevent shearing injuries, unless contraindicated due to the patient’s clinical condition.

The role of nutrition in pressure ulcer interventions has been controversial. The NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA has two recommendations with the strength of evidence at the A level (Box 13-1).1 In a large prospective cohort study, Bergstrom and Braden40 found that nursing home residents who developed pressure ulcers had a significantly lower intake of protein. Clinicians need to ensure that a patient’s caloric, protein, vitamin, and mineral needs are met. Recommendations from the dietitian can be an important source of assistance in helping patients to get their required nutrients.

Physical and occupational therapists are important members of the pressure ulcer team and a valuable resource for maximizing patient mobility. Their expertise in selecting appropriate-size wheelchairs and evaluating seating angles and postural alignment can’t be overemphasized. Patients who are confined to a chair should be repositioned every hour, with small shifts in weight made every 15 minutes. In the past, many clinicians considered turning and repositioning bedridden patients every 2 hours to be a standard of care. However, the NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA clinical guideline recommends that repositioning should take into account the individual’s condition and type of pressure redistribution support surface.1 The appropriate turning interval for all patients has yet to be determined by research. A 2-hour interval may be too long for some patients, whereas for others, every 2 hours may not be necessary, such as for palliative care patients in whom frequent repositioning would cause more pain and suffering than benefit. Because there is no standard time interval or frequency for repositioning all patients, a repositioning schedule needs to be individualized for each patient. The most recent NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA guideline1 provides evidence that repositioning frequency may be influenced by the type of support surface being used. Contrary to the earlier AHCPR (AHRQ) recommendation for every 2-hour turning/repositioning,3,4 evidence from Defloor et al.71 and Vanderwee et al.72 found that turning a patient every 4 hours on a viscoelastic mattress resulted in a significant reduction in the incidence of pressure ulcers. Bergstrom and colleagues found that for moderate- to high-risk residents in long-term care who were on high-density foam mattresses, the turning schedule could be 2, 3, or 4 hours.73

Practice Point

Practice Point

Repositioning schedules should take into consideration the condition of the patient and the support surface in use.1

The NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA clinical guideline has provided new recommendations regarding the repositioning of critically ill person that are at the C strength of evidence.1 This includes beginning a repositioning schedule as soon as possible after the patient is admitted and revising the schedule based on the patient’s tolerance to repositioning (two thumbs up).1 They recommend considering the use of slow, gradual turns that allow the patient sufficient time to stabilize their hemodynamic and oxygenation status.1 Also, clinicians should consider more frequent small shifts for critically ill persons that cannot tolerate frequent major shifts in position.1 They caution that these small shifts are a temporary intervention done in conjunction with appropriate use of a redistribution support surface and should be replaced with routine repositioning when the person’s hemodynamic status has stabilized.1 If it is determined for medical reason that a patient who is hemodynamically unstable, or has spinal instability, cannot be turned, then clinicians should evaluate the need to change the patients support surface from a reactive to an active support surface.1

Appropriate pressure-relieving devices and surfaces need to be used. Rastinehad reported that using support surfaces can decrease the incidence of pressure ulcers in at-risk oncology patients.74 Devices such as “donut cushions” should not be used1. The type and amount of linens used may make a different in pressure ulcer incidence.1 Limit the amount of linen and incontinence pads placed on the support surface/bed.1 “General rule of thumb is less is best.”1 Evidence suggests that silklike bed linens or cotton-blend fabrics reduce shear, friction, and pressure ulcer incidence.75–77 The results of a Canadian study have led to a model for use in support surface selection.78 See the NPUAP Web site (http://www.npuap.org) to review the latest definitions of physical concepts related to support surfaces as developed by the NPUAP Support Surface Standards Initiative.79 (Also, see Chapter 11, Pressure Redistribution: Seating, Positioning, and Support Surfaces.)

Ongoing monitoring and documentation are essential. In a pilot study, Horn et al.80 found that establishing a multidisciplinary team and redesigning documentation processes for certified nursing assistants in several long-term care facilities throughout the United States resulted in a decrease in the required facility documentation. For the seven facilities in the study, there was a combined 33% reduction in pressure ulcers.80

Milne et al.81 decreased facility-acquired pressure ulcer prevalence from 41% to 4.2% in a 108-bed long-term acute care hospital (LTACH) by developing policies that were supported by published clinical practice guidelines and incorporating them into the facility’s plan of care. They established a wound care team, improved documentation methods, and educated the staff. They also reviewed the facility’s wound products and revised its electronic record. All of these efforts resulted in care improvement outcome.81

Communication of the prevention plan to all members of the healthcare team, including patients and their families, is imperative. Supplement your verbal teaching with one of the prevention booklets designed for use by the consumer, such as pamphlets available from wound care companies as well as the AHRQ. The AHRQ82 also has a pressure ulcer patient guide available in Spanish.

Pressure Ulcer Staging

A comprehensive wound assessment includes many parameters, one of which is staging. (See Chapter 6, Wound assessment.) Once the wound etiology is known, the correct classification system to describe the wound can be selected. For example, arterial and venous ulcers are described by their characteristics. Diabetic or neuropathic ulcers are classified by the American Diabetes Association, Wagner Grading System for Vascular Wounds, or San Antonio Diabetic Wound Classification System. The NPUAP staging system was designed specifically for pressure ulcers. An outcome of the first NPUAP consensus conference83 was the NPUAP staging system for pressure ulcers, which was based on staging systems by Shea84 and the International Association of Enterostomal Therapists85 (now called WOCN). In February 2007, NPUAP once again revised its staging system.86 The latest revision of the pressure ulcer classification system to include six categories or stages was included in the 2014 NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA international pressure ulcer guideline.1

Pressure ulcer staging is a classification system to describe the level of tissue destroyed. It provides practitioners with a common language to communicate with each other what the pressure ulcer looks like clinically. This staging system should only be used to describe pressure ulcers and not other types of skin or wound injuries. NPUAP states that mucous membrane pressure ulcers should not be staged using its pressure ulcer staging system.24 Mucosal pressure ulcers (MPrU) are “pressure ulcers found on mucous membranes with a history of a medical device in use at the location of the ulcer”24 (Fig. 13-6). Staging is only part of the total assessment of an ulcer; a comprehensive assessment also includes factors such as the state of surrounding skin and presence of infection, among others. (See Chapter 6, Wound assessment.)

Figure 13-6. Mucosal pressure ulcer.

After the present on admission (POA) indicator went into effect in the acute care setting, confusion existed as to whether nurses could continue to stage pressure ulcers. An NPUAP position statement87 as well as information in the literature from the American Nurses Association (ANA) reaffirms that pressure ulcer staging is within the scope of practice for RNs.88,89

NPUAP Classification of Pressure Ulcers Staging Definitions

Pressure ulcers are classified according to the amount of visible tissue loss.1 Necrotic ulcers cannot be staged numerically because visualization of the wound bed is necessary to determine the level of tissue involvement; therefore, necrotic ulcers are classified as unstageable pressure ulcers. Numerical staging of necrotic wounds should be done after the necrotic tissue is removed. (See Chapter 8, Wound debridement.)

The NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA classification system1 for staging or categories of pressure ulcers is described below.

Stage I

The original definition of a stage I pressure ulcer was “nonblanchable erythema of intact skin, the heralding lesion of skin ulceration.”83 Given the diversity of people with different skin pigmentation, detecting stage I pressure ulcers can be a challenge if clinicians only use color as an indicator. In 1997, to provide a more culturally sensitive definition, NPUAP revised the definition of a stage I ulcer to include indicators that went beyond color. NPUAP continued to refine this definition to include “intact skin with nonblanchable redness of a localized area usually over a bony prominence.” In darkly pigmented skin, the area may not have visible blanching and its color may differ from surrounding skin (Box 13-1).

Persons with darkly pigmented skin have the lowest prevalence of stage I pressure ulcers.90,91 The incidence of pressure ulcers was higher in people with darkly pigmented skin in several studies conducted by Lyder and colleagues.92,93 Sprigle and colleagues94 found that warmth or coolness was present in 85% of patients with stage I pressure ulcers. Rosen and colleagues used a quality improvement program for educating staff on assessing the subtle differences in skin color, texture, and warmth in individual with darkly pigmented skin. This resulted in eliminating the racial disparity differences in PU rates between darkly pigmented and lightly pigmented residents.95 Differences in PU incidence rates may not be due to skin tone differences, but rather, cultural, social, or economic factors’ further research may shed new light on this view point.96

Staging Concepts

Staging Competency

Accuracy in staging pressure ulcers is a challenge. Nurses have reported being less confident in identifying stage III ulcers.97–101 Clinicians can test their ability to classify pressure ulcers by taking the ePUCLAS2 staging test (available in English and other languages) on the EPUAP Web site (http://www.epuap.org)102 or the quiz on the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (NDNQI) educational modules.103

Suspected Deep Tissue Injury

Clinicians often struggle with the concept of suspected deep tissue injury (sDTI)104 that presents as a purplish color, most often seen in the heel area. Typically, these wounds appear as dusky, boggy, or discolored areas of purple ecchymosis (Fig. 13-7). Sometimes, they appear a few days after surgery as a discolored area on the sacrum and may be misidentified as a burn.105 Often, these areas deteriorate rapidly from intact skin to deep open wounds.

Figure 13-7. Suspected deep tissue injury. © J. M. Levine, MD

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree