Population-Focused Practice

The Foundation of Specialization in Public Health Nursing

Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to do the following:

1. State the mission and core functions of public health and the essential public health services.

3. Contrast clinical community health nursing practice with population-focused practice.

4. Describe what is meant by population-focused practice.

5. Name barriers to acceptance of population-focused practice.

6. State key opportunities for population-focused practice.

7. Recognize quality performance standards program in public health.

Key Terms

aggregate, p. 12

assessment, p. 7

assurance, p. 7

capitation, p. 18

community-based nursing, p. 16

Community Health Improvement Process (CHIP), p. 8

community health nurses, p. 15

cottage industry, p. 18

integrated systems, p. 18

managed care, p. 4

policy development, p. 7

population, p. 12

population-focused practice, p. 11

public health, p. 7

public health core functions, p. 7

public health nursing, p. 9

Quad Council, p. 9

subpopulations, p. 12

—See Glossary for definitions

Carolyn A. Williams, RN, PhD, FAAN

Carolyn A. Williams, RN, PhD, FAAN

Dr. Carolyn A. Williams is Dean Emeritus and Professor at the College of Nursing at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky. Dr. Williams began her career as a public health nurse. She has held many leadership roles, including President of the American Academy of Nursing; membership on the first U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, Department of Health and Human Services; and President of the American Association of Colleges of Nursing. She received the Distinguished Alumna Award from Texas Woman’s University in 1983. In 2001 she was the recipient of the Mary Tolle Wright Founder’s Award for Excellence in Leadership from Sigma Theta Tau International, and in 2007 she received the Bernadette Arminger Award from the American Association of Colleges of Nursing.

The second decade of the twenty-first century finds the United States entering an era when more public attention is being given to efforts to protect and improve the health of the American people and the environment. The continuing increase in the cost of medical care also has the attention of the public and policy makers. Despite what many see as a failure to make fundamental changes in the delivery and financing of health care, significant change has occurred. Federal and state initiatives, private market forces, the development of new scientific knowledge and new technologies, and the expectations of the public are bringing about changes in the health care system. With the national legislation that passed in 2010—the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (www.healthcare.gov/law/introduction/index.html)—which in part was designed to increase access to care, concerns have been raised about the availability of adequate numbers of professional personnel to provide services, particularly in primary care and strained health care facilities. Despite some of the insurance reforms in the legislation, many citizens and businesses remain concerned about their ability to maintain affordable insurance coverage; at the national level serious concern exists regarding the growing cost of health care as a part of federal expenditures (Orszag, 2007; 2010). Other health system concerns focus on the quality and safety of services, warnings about bioterrorism, and global public health threats such as infectious diseases and contaminated foods. Because of all of these factors, the role of public health in protecting and promoting health, as well as preventing disease and disability, is extremely important.

Whereas the majority of national attention and debate surrounding national health legislation has been focused primarily on insurance issues related to medical care, there are indications of a renewed interest in public health and in population-focused thinking about health and health care in the United States. For example, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act contains a number of provisions that address health promotion and prevention of disease and disability. These include (1) establishing the National Prevention, Health Promotion and Public Health Council to coordinate federal prevention, wellness, and public health activities and to develop a national strategy to improve the nation’s health, and (2) creating a Prevention and Public Health Fund to expand and sustain funding for prevention and public health programs, and (3) improving prevention by covering only proven preventive services and eliminating state cost sharing for preventive services, including immunizations recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Also grants and technical assistance will be available to employers who establish wellness programs (PPACAHCEARA, healthcare.gov, 2010).

Although populations have historically been the focus of public health practice, populations are also the focus of the “business” of managed care; therefore public health practitioners and managed care executives are both population oriented. Increasingly, managed care executives and program managers are using the basic sciences and analytic tools of the field of public health. They focus particularly on epidemiology and statistics to develop databases and approaches to making decisions at the level of a defined population or subpopulation. Thus a population-focused approach to planning, delivering, and evaluating nursing care has never been more important.

Where is public health nursing in all of the changes swirling around in the world of health and health care? This is a crucial time for public health nursing, a time of opportunity and challenge. The issue of growing costs together with the changing demography of the U. S. population, particularly the aging of the population, is expected to put increased demands on resources available for health care. In addition, the threats of bioterrorism, highlighted by the events of September 11, 2001, and the anthrax scares, will divert health care funds and resources from other health care programs to be spent for public safety. Also important to the public health community is the emergence of modern-day epidemics (such as the mosquito-borne West Nile virus, and the H1N1 influenza virus) and globally induced infectious diseases such as avian influenza and other causes of mortality, many of which affect the very young. Most of the causes of these epidemics are preventable. What has all of this to do with nursing?

Understanding the importance of community-oriented, population-focused nursing practice and developing the knowledge and skills to practice it will be critical to attaining a leadership role in health care regardless of the practice setting. The following discussion explains why those who practice population-focused nursing in the context of community-based programs directed to populations will be in a very strong position to affect the health of populations and the decisions about how scarce resources will be used.

Public Health Practice: the Foundation for Healthy Populations and Communities

During the last 20 years, considerable attention has been focused on proposals to reform the American health care system. These proposals focused primarily on containing cost in medical care financing and on strategies for providing health insurance coverage to a higher proportion of the population. In the national health legislation that passed in 2010, The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, the majority of the provisions and the vast majority of the discussion of the bill focused on those issues (PPACAHCEARA, 2010).

Because physician services and hospital care combined account for over half of the health care expenditures in the United States, it is understandable that changes in how such services would be paid for would receive much attention (kaiseredu.org, 2010). However, many times the most benefit from the least cost is sought in the wrong place. As stated in the Public Health Services Steering Committee Report on the Core Functions of Public Health (1998), reform of the medical insurance system was thought to be necessary, but it was not adequate to improve the health of Americans.

Historically, gains in the health of populations have come largely from public health changes. Safety and adequacy of food supplies, the provision of safe water, sewage disposal, public safety from biological threats, and personal behavioral changes, including reproductive behavior, are a few examples of public health’s influence. The dramatic increase in life expectancy for Americans during the 1900s, from less than 50 years in 1900 to 77.9 years in 2007, is credited primarily to improvements in sanitation, the control of infectious diseases through immunizations, and other public health activities (USDHHS, 2010a). Population-based preventive programs launched in the 1970s were also largely responsible for the more recent changes in tobacco use, blood pressure control, dietary patterns (except obesity), automobile safety restraint, and injury control measures that have fostered declines in adult death rates. There has been more than a 50% decline in stroke and coronary heart disease deaths. Overall death rates for children have declined by about 40% (USDHHS, 2010).

Another way of looking at the benefits of public health practice is to look at how early deaths can be prevented. The U.S. Public Health Service estimates that medical treatment can prevent only about 10% of all early deaths in the United States. However, population-focused public health approaches have the potential to help prevent approximately 70% of early deaths in America through measures targeted to the factors that contribute to those deaths. Many of these contributing factors are behavioral, such as tobacco use, diet, and sedentary lifestyle. Other factors that affect health are the environment, social conditions, education, culture, economics, working conditions, and housing (Healthy People 2020, USDHHS, 2010b).

Public health practice is of great value. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) (2010) estimated that in 2008 only 3% (up from 1.5% in 1960) of all national health expenditures support population-focused public health functions, yet the impact is enormous. Unfortunately, the public is largely unaware of the contributions of public health practice. Federal and private monies were sparse in their support of public health, so public health agencies began to provide personal care services for persons who could not receive care elsewhere. The health departments benefited by getting Medicaid and Medicare funds. The result was a shift of resources and energy away from public health’s traditional and unique population-focused perspective to include a primary care focus (USDHHS, 2002).

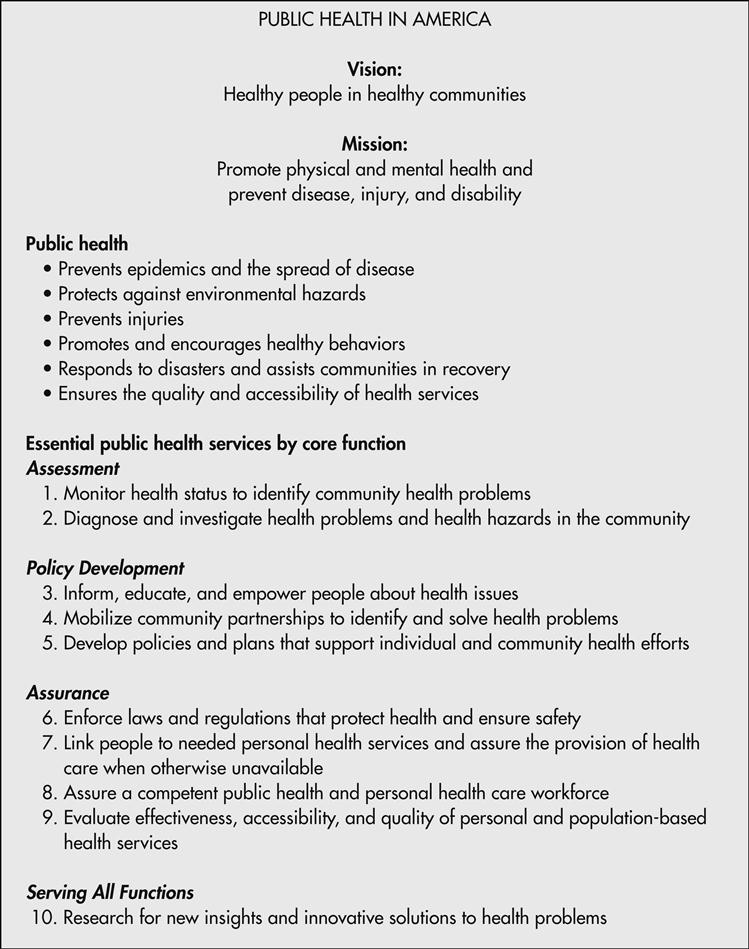

Because of the importance of influencing a population’s health and providing a strong foundation for the health care system, the U.S. Public Health Service and other groups strongly advocated a renewed emphasis on the population-focused essential public health functions and services, which have been most effective in improving the health of the entire population. As part of this effort, a statement on public health in the United States was developed by a working group made up of representatives of federal agencies and organizations concerned about public health. The list of essential services presented in Figure 1-1 represents the obligations of the public health system to implement the core functions of assessment, assurance, and policy development. The How To box further explains these essential services and lists the ways public health nurses implement them (U.S. Public Health Service, 1994/update 2008).

Definitions in Public Health

In 1988 the Institute of Medicine published a report on the future of public health, which is now seen as a classic and influential document. In the report, public health was defined as “what we, as a society, do collectively to assure the conditions in which people can be healthy” (IOM, 1988, p. 1). The committee stated that the mission of public health was “to generate organized community effort to address the public interest in health by applying scientific and technical knowledge to prevent disease and promote health” (IOM, 1988, p. 1; Williams, 1995).

It was clearly noted that the mission could be accomplished by many groups, public and private, and by individuals. However, the government has a special function “to see to it that vital elements are in place and that the mission is adequately addressed” (IOM, 1988, p. 7). To clarify the government’s role in fulfilling the mission, the report stated that assessment, policy development, and assurance are the public health core functions at all levels of government.

• Assurance refers to the role of public health in ensuring that essential community-oriented health services are available, which may include providing essential personal health services for those who would otherwise not receive them. Assurance also refers to making sure that a competent public health and personal health care workforce is available. More recently, Fielding (2009) made the case that assurance also should mean that public health officials should be involved in developing and monitoring the quality of services provided.

Public Health Core Functions

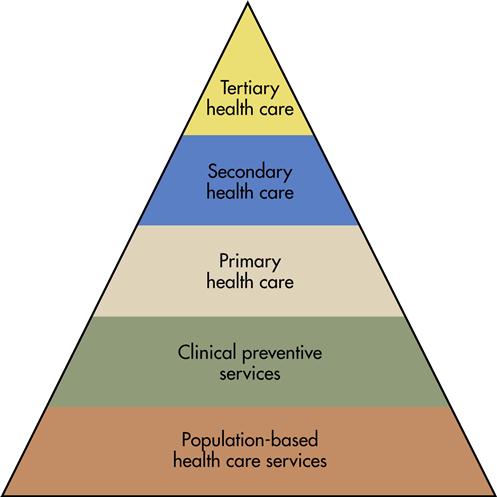

The Core Functions Project (U.S. Public Health Service, 1994/2008) developed a useful illustration, the Health Services Pyramid (Figure 1-2), which shows that population-based public health programs support the goals of providing a foundation for clinical preventive services. These services focus on disease prevention; on health promotion and protection; and on primary, secondary, and tertiary health care services. All levels of services shown in the pyramid are important to the health of the population and thus must be part of a health care system with health as a goal. It has been said that “the greater the effectiveness of services in the lower tiers, the greater is the capability of higher tiers to contribute efficiently to health improvement” (U.S. Public Health Service, 1994/2008). Because of the importance of the basic public health programs, members of the Core Functions Project argued that all levels of health care, including population-based public health care, must be funded or the goal of health of populations may never be reached.

Several new efforts to enable public health practitioners to be more effective in implementing the core functions of assessment, policy development, and assurance have been undertaken at the national level. In 1997 the Institute of Medicine published Improving Health in the Community: A Role for Performance Monitoring (IOM, 1997). This monograph was the product of an interdisciplinary committee, co-chaired by a public health nursing specialist and a physician, whose purpose was to determine how a performance monitoring system could be developed and used to improve community health.

The major outcome of the committee’s work was the Community Health Improvement Process (CHIP), a method for improving the health of the population on a community-wide basis. The method brings together key elements of the public health and personal health care systems in one framework. A second outcome of the project was the development of a set of 25 indicators that could be used in the community assessment process (see Chapter 18) to develop a community health profile (e.g., measures of health status, functional status, quality of life, health risk factors, and health resource use) (Box 1-1). A third product of the committee’s work was a set of indicators for specific public health problems that could be used by public health specialists as they carry out their assurance function and monitor the performance of public health and other agencies.

In 2000 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) established a Task Force on Community Preventive Services (CDC, 2000). The Task Force worked to collect evidence on the effectiveness of a variety of community interventions to prevent morbidity and mortality. The effort has resulted in a versatile set of resources that can be used by public health specialists and others interested in a community-level approach to health improvement and disease prevention. Information is available on 16 topics, which include health problems/issues such as obesity, vaccines, asthma, cancer, diabetes, and concerns such as violence, tobacco, nutrition, and worksite initiatives (CDC, 2005). The materials, which include systematic reviews of research, can be used to help make choices about policies and programs that have been shown to be effective (CDC, 2010). The material can be found at the project’s website, www.thecommunityguide.org/index.html. Collaborative efforts such as the Task Force on Community Preventive Services are important because they provide tools for public health practitioners, many of whom are public health nursing specialists, to enable them to be more effective in dealing with the core functions.

Core Competencies of Public Health Professionals

To improve the public health workforce’s abilities to implement the core functions of public health and to ensure that the workforce has the necessary skills to provide the 10 essential services listed in Figure 1-1, a coalition of representatives from 17 national public health organizations has been working since 1992 on collaborative activities to “assure a well-trained, competent workforce and a strong, evidence-based public health infrastructure.” (USPHS, 1994/2008). In the spring of 2010 this Council, funded by the CDC and DHHS, adopted an updated set of Core Competencies (“a set of skills desirable for the broad practice of public health”) (Council on Linkages, 2010) for all public health professionals, including nurses. The 72 Core Competencies are divided into eight categories (Box 1-2). In addition, each competency is presented at three levels (tiers), which reflect the different stages of a career. Specifically, Tier 1 applies to entry level public health professionals without management responsibilities. Tier 2 competencies are expected in those with management and/or supervisory responsibilities, and Tier 3 is expected of senior managers and/or leaders in public health organizations. It is recommended that these categories of competencies be used by educators for curriculum review and development and by agency administrators for workforce needs assessment, competency development, performance evaluation, hiring, and refining of the personnel system job requirements. A detailed listing of these competencies can be found at www.phf.org/link/index.htm.

Using an earlier version of the Council on Linkage’s Core Competencies as a starting point, a group of public health nursing organizations called the Quad Council developed levels of skills to be attained by public health nurses for each of the competencies. Skill levels are specified for the generalist/staff nurse and the specialist in public health nursing (Quad Council, 2003/2009). See Resource Tool 45.A on the Evolve website for the Public Health Nursing Core Competencies.

National Public Health Performance Standards Program

In the same time period, the Institute of Medicine released a report, “Who Will Keep the Public Healthy?” (2003b) that identified eight content areas in which public health workers should be educated—informatics, genomics (Box 1-3), cultural competence, community-based participatory research, policy, law, global health, and ethics—in order to be able to address the emerging public health issues and advances in science and policy.