Family Health Risks

Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to do the following:

1. Evaluate the various approaches to defining and conceptualizing family health.

2. Analyze the major risks to family health.

3. Analyze the interrelationships among individual health, family health, and community health.

5. Discuss the implications of policy and policy decisions, at all governmental levels, on families.

Key Terms

behavioral risk, p. 628

biological risk, p. 628

contracting, p. 640

economic risk, p. 633

empowerment, p. 641

family crisis, p. 629

family health, p. 625

health risk appraisal, p. 628

health risk reduction, p. 628

health risks, p. 626

home visits, p. 637

in-home phase, p. 639

initiation phase, p. 638

life-event risk, p. 630

policy, p. 625

post-visit phase, p. 640

pre-visit phase, p. 638

risk, p. 627

social risks, p. 633

termination phase, p. 640

transitions, p. 630

—See Glossary for definitions

Debra Gay Anderson, PhD, PHCNS, BC

Debra Gay Anderson, PhD, PHCNS, BC

Dr. Debra Gay Anderson is currently an associate professor of nursing at the University of Kentucky’s College of Nursing in Lexington. She is certified as a clinical specialist in public/community health nursing and has provided health care for the homeless and other vulnerable populations. Dr. Anderson has taught public health, epidemiology, leadership, and research courses at both the graduate and undergraduate levels. The focus of her program of research, publications, and presentations is vulnerable populations, primarily women who are statistically at greater risk of experiencing domestic violence or workplace violence. Dr. Anderson has also completed a family nursing postdoctoral fellowship at Oregon Health Sciences University in Portland, Oregon. Dr. Anderson is an active member of the American Public Health Association (APHA) and has served in various leadership capacities, including Chair of the Public Health Nursing Section of APHA.

Amanda Fallin, RN, MSN

Amanda Fallin, RN, MSN

Amanda Fallin graduated from the University of Kentucky in 2009 with a Master of Science in Nursing degree. She is currently working on her PhD at the University of Kentucky’s College of Nursing. While in graduate school, Ms. Fallin has worked as a research assistant to Drs. Anderson and Ellen Hahn, participating in grant and manuscript preparation and poster presentations at the national conference of the American Public Health Association and the Southern Nursing Research Society.

The family as a client unit is basic to the practice of population-centered nursing, and nurses are responsible for promoting healthy families in society. As such, families are described as a unique population in public health. The purpose of this chapter is to make the reader aware of influences, both individual and societal, that place families at risk for poor health outcomes, and to discuss how positive outcomes for diverse families can be accomplished through appropriate nursing interventions.

The expanding definition of the family unit presents today’s nurse with an array of challenges and opportunities to address the health needs of families. First, it is essential to place the family in the context of the twenty-first century. Many Americans tend to idealize family and wish for a return to family values of the past and a golden time for families. However, historical demographic statistics reveal that this prevalence of the idealized family that has often been portrayed in the media never actually existed. Rather than arguing for a return to the “traditional family” (male breadwinner and woman at home), serious discussions are needed about how to help today’s diverse families succeed. A focus on all family structures is a moral and ethical imperative in the promotion of the health of individuals as well as the health of the community (Nightingale et al, 1978; Wright and Leahey, 2009).

The varying family structures of today need to be recognized and examined in order to better understand both the strengths and weaknesses associated with each. Only by doing this will we be able to help all families live healthy and productive lives. Nurses can play an active role in leading and facilitating this learning process. This facilitation can enable better-informed health care policy decisions that have a positive effect on single-parent families, remarried and stepfamilies, gay and lesbian families, grandparent-headed families, and ethnically diverse families, as well as “traditional” families.

A nation’s family health care policy is a primary determinant of family health. Family policy means anything that is done by the government that directly or indirectly affects families. Family health policy and its relative effectiveness demonstrates a government’s understanding of families and its role in promoting their health, with an important desired outcome being that families derive a sense of empowerment and are able to take responsibility for their own health (Chinn, 2008). The responsibility for family health programs is shared by the federal government with state and local governments. Each state, as well as regions within states, has programs and laws related to family services. The United States is one of the richest and most technologically advanced countries in the world today and yet, despite the profusion of technological advances and the continually growing proportion of the national budget spent on health care, the disparities in health status between different populations of families has continued to grow (Families USA, 2009). These disparities have resulted, at least in part, from previous attempts to develop and implement “family policies” that either directly or indirectly affect specific issues related to family health but which have failed to take a comprehensive system–wide approach. An example of this is the recent Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 that aims to help families who are currently uninsured or underinsured to obtain insurance coverage. Although well intended, it may well turn out to be just one more piece in an incomplete patchwork of existing legislation that is struggling to effectively improve family health.

Evidence to date suggests that the United States could benefit from a cohesive family policy designed to enhance the well-being of all families. Such a policy would go a long way to prevent future crises in vulnerable family populations, such as those in or on the verge of poverty, or families overwhelmed with abuse and neglect, by providing a structural safety net to help families to maintain their health in times of disaster, economic downturns, unemployment, health crises, and other situations. An effective family health policy may consider as its foundational element an infrastructure of programs designed to provide access to primary and preventive health care. The building of this foundation requires a multi-professional process in which nurses can be actively involved. Nurses are educated in community assessment, planning, development, and evaluation activities that emphasize and address issues crucial to promoting and sustaining primary family health. Nurses looking to positively influence family health will want to be aware of and actively participate in the ongoing national debate and dialogue on family health policy that embraces their role as principal constituents in building healthy families.

In establishing health objectives for the nation, an emphasis has been placed on both health promotion and risk reduction. Reducing the risks to segments of the population is a direct way to improve the health of the general population. Specific objectives have been identified related to specific health risks for families. The family is an important environmental factor that affects the health of individuals as well as a social unit whose health is basic to that of the community and the larger population. It is within the family that health values, health habits, and health risk perceptions are developed, organized, and carried out. Individuals’ health behaviors are affected by and acted out within the family environment, the larger community, and society. Family health habits are developed in the same manner in the context of community norms and values, and on the basis of availability and accessibility. For example, in a television commercial for an over-the-counter stimulant, a man is featured who is able to coach his child’s basketball team, work at a rehabilitation center, and work as a borough inspector for the city, all while pursuing a college degree at night. The commercial credits the drug for providing the man with the energy needed to be successful in all of these areas. The message is clear: you can, and must, do it all, and taking drugs to succeed is a viable option. The health risks to individual and family health are affected by the societal norms—in this example, the norm is increasing productivity through drugs.

To intervene effectively and appropriately with families to reduce their health risk and thereby promote their health, nurses need to understand not only family structure and functioning, but also family theory, nursing theory, and models of health risk (see Chapters 9, 17, and 27). In addition, the effective nurse needs to look beyond the individual and the family in order to understand the complex environment in which the family exists. Increasing evidence of the effects of social, biological, economic, and life events on health requires a broader approach to addressing health risks for families. Nurses and the communities they serve have a vital interest in exploring new and appropriate options for structuring nursing interventions with families to decrease health risks and to promote health and well-being for all families. It is important for the nurse to focus on families who share similar health risks as a population. Working and planning interventions to reduce health risks in family populations provides a mechanism for shared communication and support among families as well as efficient and effective health care interventions that will not only make the families, but the community as a whole, healthier.

Early Approaches to Family Health Risks

Health of Families

Historically, the study of the family relative to health and illness focused on three major areas: (1) the effect of illness on families, (2) the role of the family in the cause of disease, and (3) the role of the family in its use of services. In his classic review of the family as an important unit, Litman (1974) pointed out the important role that the family (as a primary unit of health care) plays in health and illness and emphasized that the relationship between health, health behavior, and family “is a highly dynamic one in which each may have a dramatic effect on the other” (p 495). At about this same time, Mauksch (1974) proposed the idea of distinguishing between family health and individual health. Pratt’s (1976) examination of the role of the family in health and illness included the role of family health in the promotion of healthy or unhealthy behavior. Pratt proposed and described the energized family as being an ideal family type that was most effective in meeting health needs. The energized family is characterized as promoting freedom and change, active contact with a variety of other groups and organizations, flexible role relationships, equal power structure, and a high degree of autonomy in family members. Doherty and McCubbin (1985) proposed a family health and illness cycle consisting of six phases, beginning with family health promotion and risk reduction and continuing through the family’s vulnerability to illness, their illness response, their interaction with the health care system, and finally their ways of adapting to illness.

Health of the Nation

In recent years, increased attention has been given to improving the health of everyone in the United States. As a result of major public health and scientific advances, the leading causes of morbidity and mortality have shifted from infectious diseases to chronic diseases, accidents, and violence, all of which have strong lifestyle and environmental components. A classic population-focused study in Alameda County, California (Belloc and Breslow, 1972) demonstrated the relationships between seven lifestyle habits and decreased morbidity and mortality. These habits were: (1) sleeping 7 to 8 hours daily, (2) eating breakfast almost every day, (3) never or rarely eating between meals, (4) being at or near recommended height-adjusted weight, (5) never smoking cigarettes, (6) moderate or no use of alcohol, and (7) regular physical activity. These same lifestyle health habits are still important for improved health in the twenty-first century.

A growing body of literature supports the notion that lifestyle and the environment interact with heredity to cause disease. In response to these findings and to the limited effect of medical interventions on the growing incidence and prevalence of injuries and chronic disease, the government launched a major effort to address the health status of the population. Part of this effort was a report by the Division of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention of the Institute of Medicine that examined the critical components of the physical, socioeconomic, and family environments related to decreasing risk and promoting health (Nightingale et al, 1978). The Surgeon General’s Report on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention (Califano, 1979) described the risks to good health in the United States at that time. As a result of these reports, health objectives for the nation were established and then evaluated and restated for the year 2000 and again for 2010 (USDHHS, 2000). The Healthy People 2020 objectives extend the work of the three past documents. An innovative part of this latest Healthy People update has been a move to become more creative and inclusive. The focus challenges health care providers with a national goal of improving health and will provide the necessary background for future policy initiatives to reduce risk in all populations. Of the four goals, three are particularly important to families:

• Achieve health equity, eliminate disparities, and improve the health of all groups.

• Create social and physical environments that promote good health for all.

• Promote quality of life, healthy development, and healthy behaviors across all life stages.

With the notion of risk, any factor resulting in a predisposition toward or an increased likelihood of ill health takes on increased importance. Specific attention is being paid to those environmental and behavioral factors that lead to ill health with or without the influence of heredity. Reducing health risks is a major step toward improving the health of the nation. Although the family is considered an important environment related to achieving important health objectives, limited attention and research have been directed at family health risks and the role of society in promoting healthy families.

Concepts in Family Health Risk

Pender’s Health Promotion Model (2010), described in the latest edition of her textbook, continues to be useful in research that is done with families. This health promotion model states there are two factors that motivate individuals to participate in positive health behaviors. One is a desire to promote one’s own health, using behaviors that have been determined to increase the individual, family, community and society’s well-being, and in the process, actually moving toward not only individual self actualization, but a society actualization as well. The second factor is a desire to protect health, using those same behaviors in an effort to decrease the probability of ill health and provide active protection against illness and dysfunction in families (Pender, 2010). Understanding family health risk requires an examination of several related concepts: family health, family health risk, risk appraisal, risk reduction, life events, lifestyle, and family crisis. These concepts will be defined and discussed here. It important to remember that health can be defined in a number of ways, and it is defined by individuals and families within their own culture and value system.

Family Health

Family theorists refer to healthy families but generally do not define family health (White and Klein, 2009). Based on the variety of perspectives of family (see Chapters 9, 17, and 27), definitions of healthy families can be derived within the guidelines of the framework associated with that perspective. For example, within the perspective of the developmental framework, family health can be defined as possessing the abilities and resources to accomplish family developmental tasks. Thus, the accomplishment of stage-specific tasks is one indicator of family health.

Because the family unit is a part of many societal systems, the systems perspective will be discussed in more detail. Using the Neuman Systems Model (Nursing Theory Network, 2005; Neumann University, 2010), family health is defined in terms of system stability as characterized by five interacting sets of factors: physiological, psychological, sociocultural, developmental, and spiritual. The client family is seen as a whole system with the five interacting factors. The Neuman Systems Model is a wellness-oriented model in which the nurse uses the strengths and resources of the family to keep the system stable while adjusting to stress reactions that lead to health change and wellness. In other words, this model focuses on family wellness in the face of change. Because change is inevitable in every family, the Neuman Systems Model proposes that families have a flexible external line of defense, a normal line of defense, and an internal line of resistance. When a life event is big enough to contract the flexible line of defense (a protective mechanism) and breaks through the normal line of defense, the family feels stress. The degree of wellness is determined by the amount of energy it takes for the system to become and remain stable. When more energy is available than is being used, the system remains stable. Examples of energy-building characteristics in this system are social support, resources, and prevention (or avoidance) of stressors. Nurses can use preventive health care both to reduce the possibility that a family encounters a stressor and to help strengthen the family’s flexible line of defense. The following clinical example applies the Neuman Systems Model to one family’s situation:

The Harris family consists of Ms. Harris (Gloria), 12-year-old Kevin, 8-year-old Leisha, and Ms. Harris’s mother, 75-year-old Betty. Kevin was recently diagnosed with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, and the family was referred by the endocrinology clinic to the nursing service at the local health department to work with the family in adjusting to the diagnosis.

The focus of the Neuman Systems Model would be to assess the family’s ability to adapt to this stressful change and then focus on their strengths in the stabilizing process. The five interacting variables would compose an important component of the assessment:

Health Risk

Several factors contribute to the development of healthy or unhealthy outcomes. Clearly, not everyone exposed to the same event will have the same outcome. The factors that determine or influence whether disease or other unhealthy results occur are called health risks. Controlling health risks is done through disease prevention and health promotion efforts. Health risks can be classified into general categories: inherited biological risk (including age-related risks), social and physical environmental risks and behavioral risk as well as health care risks. The first three of these categories of risk is discussed later in terms of family health risk, under Major Family Health Risks and Nursing Interventions Healthy People 2020 (USDHHS, 2010).

Although single risk factors can influence outcomes, the combined effect of accumulated risks is greater than the sum of the individual effects. For example, a family history of cardiovascular disease is a single biological risk factor that is affected by smoking (a behavioral risk that is more likely to occur if other family members also smoke) and by diet and exercise. Diet and exercise are influenced by family and society’s norms. Although the demographics may be changing, residents of the Northwest and West have historically been more likely to eat heart-healthy diets and to exercise compared with people who live in the Midwest and South; thus, communities in the Northwest and West are often more supportive of exercise programs, bicycle paths, and diets lower in fat than communities in other parts of the United States. The combined effect of a family history, family behavioral risks, and society’s influences is greater than the sum of the three individual risk factors (smoking, diet, and exercise). Thus, working with populations of families and intervening within a community is more likely to reduce the effects of the health risks overall and produce a healthier community as well as a healthier family unit.

Health Risk Appraisal

Health risk appraisal refers to the process of assessing for the presence of specific factors in each of the categories that have been identified as being associated with an increased likelihood of an illness, such as cancer, or an unhealthy event, such as an automobile accident. Several techniques have been developed to accomplish health risk appraisal, including computer software programs and paper-and-pencil instruments. One technique is the Youth Behavioral Health Risk Appraisal instrument of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2010). The general approach is to determine whether and to what degree a risk factor is present. On the basis of scientific evidence, each factor is weighted, and a total score is derived. This appraisal method provides an individual score that can be examined as a whole within the family being assessed, thus appraising the health risks that are likely to be experienced by other members of the family. Additional research is needed to determine if the individual appraisals can be used to determine family risk.

Health Risk Reduction

Health risk reduction is based on the assumption that decreasing the number of risks or the magnitude of risk will result in a lower probability of an undesired event occurring. For example, to decrease the likelihood of adolescent substance abuse, family behaviors such as parents not drinking, alcohol not available in the home, and family contracts related to alcohol and drug use may be useful. Health risks can be reduced through a variety of approaches, such as those just described. It is important to note the specific risk and the family’s tolerance of it. Pender (2010) provides examples of different kinds of risks:

• Voluntarily assumed risks are better tolerated than those imposed by others.

• Risks of natural origin are often considered less threatening than those created by humans.

Family Crisis

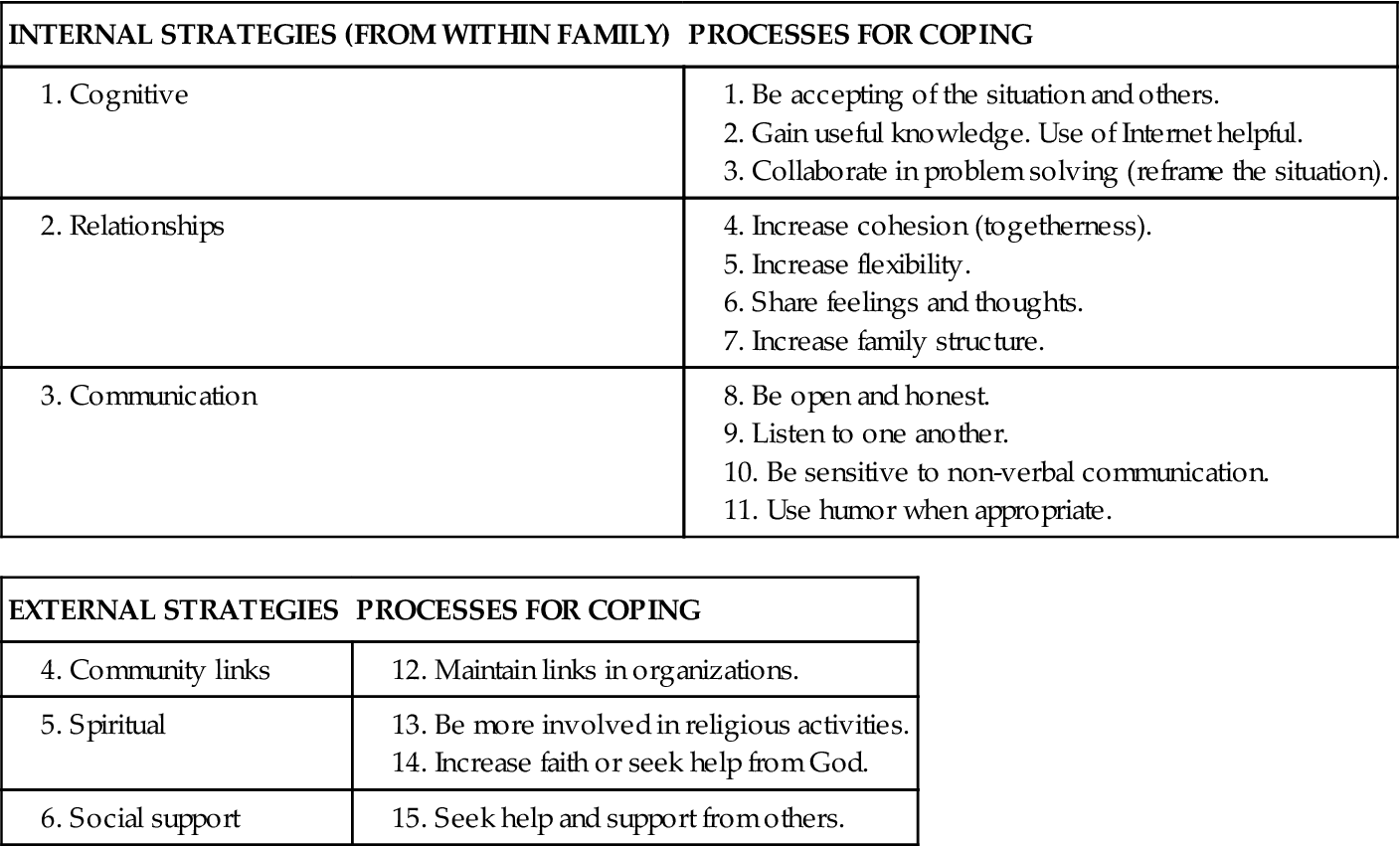

A family crisis occurs when the family is not able to cope with an event or multiple events and becomes disorganized or dysfunctional. When the demands of the situation exceed the resources of the family, a family crisis exists. When families experience a crisis or a crisis-producing event, they attempt to gather their resources to deal with the demands created by the situation. McKenry and Price (2005) differentiate between family resources and family coping strategies. The former are the resources, such as money and extended family, that a family has available to them. The latter are the family’s efforts to manage, adapt, or deal with the stressful event in order to achieve balance in the family system (McKenry and Price, 2005). Thus, if a family were to experience an unexpected illness of the primary wage earner, family resources might include financial assistance from relatives or emotional support. Family coping strategies, in contrast, would include whether the family was able to ask a relative to loan them emergency funds or was able to talk with relatives about the worries they were experiencing. On the basis of the existing literature, Friedman et al (2003) developed a system of coping strategies (Table 28-1).

TABLE 28-1

FRAMEWORK OF COPING STRATEGIES

| INTERNAL STRATEGIES (FROM WITHIN FAMILY) | PROCESSES FOR COPING |

1. Cognitive | |

| EXTERNAL STRATEGIES | PROCESSES FOR COPING |

5. Spiritual | |

From Friedman M, Bowden V, Jones E: Family nursing: research, theory & practice, ed 5, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2003, Prentice Hall.

It is important to note that the amount of support available to families in times of crisis from government and non-government agencies varies in different regions, states, and locales. In addition, the rules and conditions of support often differ and may inhibit families from seeking support, particularly if the conditions are demeaning. Nurses must be aware and sensitive to these differences in assessing the accessibility of support resources to families.

Major Family Health Risks and Nursing Interventions

As mentioned earlier, risks to a family’s health arise in three major areas: biological, environmental, and behavioral. In most instances, a risk in one of these areas may not be enough to threaten family health, but a combination of risks from two or more categories could threaten health. For example, a family history of cardiovascular disease by itself may not indicate an increased risk, but the health risk is often increased by an unhealthy lifestyle. An understanding of each of these categories provides the basis for a comprehensive perspective on family health risk assessment and intervention.

Healthy People 2020 targets areas in health promotion, health protection, preventive services, and surveillance and data systems to describe age-related objectives (USDHHS, 2010a). Included in the area of health promotion are physical activity and fitness, nutrition, tobacco use, use of alcohol and other drugs, family planning, mental health and mental disorders, and violent and abusive behavior. Health protection activities include issues related to unintentional injuries, occupational safety and health, environmental health, food and drug safety, and oral health. Preventive services, designed to reduce risks of illness, include maternal and infant health, heart disease and stroke, cancer, diabetes and other chronic disabling conditions, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, sexually transmitted diseases, immunization for infectious diseases, and clinical preventive services. The interrelationships among the various groups of risk are clear when the objectives for the nation are considered. Most of the national health objectives are based on risk factors of groups or populations in a variety of categories like age, gender, and health problems. However, it is important to recognize that some of these factors also relate to and have potential effects on the individuals’ families, work, school, and communities.

Family Health Risk Appraisal

Assessment of family health risk requires many approaches. As in any assessment, the first and most important task is to get to know the family, their strengths, and their needs (see Chapter 27). This section focuses on appraisal of family health risks in the areas of biological and age-related risk, social and physical environmental risk, and behavioral risk. Box 28-1 provides some definitions related to family health.

Biological and Age-Related Risk

The family plays an important role in both the development and the management of a disease or condition. Several illnesses have a family component that can be accounted for by either genetics or lifestyle patterns. These factors contribute to the biological risk for certain conditions. Patterns of cardiovascular disease, for example, can often be traced through several generations of a family. Such families are said to be at risk for cardiovascular disease. How or whether cardiovascular disease is found in a family is often influenced by the lifestyle of the family. Research evidence consistently supports the positive effects of diet, exercise, and stress management on preventing or delaying cardiovascular disease. The development of hypertension can be managed by following a low-sodium diet, maintaining a normal weight, exercising regularly, and using effective stress management techniques, such as meditation. Diabetes mellitus is another disease with a strong genetic pattern, and the family plays a major role in the management of the condition. Family patterns of obesity increase the risk in individuals for a number of conditions, including heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, some types of cancer, and gallbladder disease (USDHHS, 2010a). The role of genetics is becoming increasingly important. Box 28-2 discusses two examples of adult-onset hereditary diseases and offers caution about the importance of fully understanding the implications of the disease and the action to be taken. It is often difficult to separate biological risks from individual lifestyle factors.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree