Population-Centered Nursing in Rural and Urban Environments

Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to do the following:

1. Compare and contrast definitions of rural and urban.

2. Describe residency as a continuum, ranging from farm residency to core inner city.

3. Compare and contrast the health status of rural and urban populations on select health measures.

4. Analyze barriers to care in health professional shortage areas and for underserved populations.

5. Evaluate issues related to the delivery of public health services for rural underserved populations.

6. Describe characteristics of rural and small-town residency.

7. Examine the role and scope of public health nursing practice in rural and underserved areas.

Key Terms

farm residency, p. 428

frontier, p. 434

health professional shortage area (HPSA), p. 433

medically underserved, p. 443

metropolitan area, p. 429

micropolitan area, p. 429

non-core area, p. 429

non-farm residency, p. 428

rural, p. 428

rural-urban continuum, p. 429

suburbs, p. 429

urban, p. 428

—See Glossary for definitions

Angeline Bushy, PhD, RN, FAAN, PHCNS-BC

Angeline Bushy, PhD, RN, FAAN, PHCNS-BC

Dr. Angeline Bushy, Professor and Bert Fish Endowed Chair at the University of Central Florida, College of Nursing holds a BSN degree from the University of Mary in Bismarck, North Dakota; an MN degree in rural community health nursing from Montana State University in Bozeman; an MEd in adult education from Northern Montana College in Havre; and a PhD in nursing from the University of Texas at Austin. She is a Fellow in the American Academy of Nursing and a clinical specialist in public health nursing. She has worked in rural facilities located in the north-central and intermountain states; presented nationally and internationally on various rural nursing and rural health issues; published six textbooks and numerous articles on that topic; and, is a Lieutenant Colonel (Ret.) in the U.S. Army Reserve.

Access to health care is a national priority, especially in regions with an insufficient number of health care providers. Recruiting and retaining qualified health professionals can be a challenge in underserved communities, particularly inner cities and rural areas of the United States. Until recently, however, only limited research has been undertaken on the special challenges, problems, and opportunities of nursing practice—especially public health nursing in rural settings. This chapter presents major issues surrounding health care delivery in rural environments, which sometimes differs from that in urban or more populated settings. Common definitions for the term rural are discussed, as are its associated lifestyle, the health status of rural populations, barriers to obtaining a continuum of health care services, and public health nursing practice issues. Strategies are discussed to help nurses deliver more effective population-focused nursing services to clients who live in more isolated environments with sparser resources. This chapter describes rural public health nursing practice and can be used by students, nurses who practice in rural public health departments, and those who work in agencies located in urban areas that offer outreach services to rural populations in their catchment area.

Historic Overview

Formal rural nursing originated with the Red Cross Rural Nursing Service, which was organized in November 1912. The Committee on Rural Nursing was under the direction of Mabel Boardman (Chair), Jane Delano (Vice-Chair), and Annie Goodrich along with other Red Cross leaders and philanthropists (Bigbee and Crowder, 1985). Before the formation of the Red Cross Rural Nursing Service, care of the sick in a small community was provided by informal social support systems. When self-care and family care were not effective in bringing about healing, this task was assigned to healers, who often were women who lived in the local community. Historically, the health needs of rural Americans have been numerous, and although not necessarily unique, they are different from those of urban populations. Consistent problems of maldistribution of health professionals, poverty, limited access to services, ignorance, and social isolation have plagued many rural communities for generations.

Over the years, the history of the Red Cross Rural Nursing Service shows a consistent movement away from its initial rural focus, as demonstrated by its frequent name changes. Unfortunately, concern for rural health is similarly often temporary and replaced by other areas of greater need. It can be hoped that health care reform initiatives will ensure equitable access to care for rural and urban residents alike (NACRHHS, 2008; USDHHS, 2010a).

Definition of Terms

Rurality: A Subjective Concept

Everyone has an idea as to what constitutes rural as opposed to urban residence. However, the two cannot be viewed as opposing entities. With the increased degree of urban influence on rural communities, the differences are no longer as distinct as they may have been even a decade ago (Bureau of the Census, 2009; Gamm et al, 2003; USDA, 2005, 2006, 2008a,b). In general, rural is defined in terms of the geographic location and population density, or it may be described in terms of the distance from (e.g., 20 miles) or the time (e.g., 30 minutes) needed to commute to an urban center.

Both urban and rural communities are highly diverse and vary in their demographic, environmental, economic, and social characteristics. In turn, these characteristics influence the magnitude and types of health problems that communities face. Urban counties, however, tend to have more health care providers in relation to population, and residents of more rural counties often live farther from health care resources (CDC, 2010; Cromartie, 2008; Mead et al, 2008).

Some equate the idea of rural with farm residency and urban with non-farm residency, whereas others consider rural to be a “state of mind.” For the more affluent, rural may bring to mind a recreational, retirement, or resort community located in the mountains or in lake country where one can relax and participate in outdoor activities, such as skiing, fishing, hiking, or hunting. For the less affluent, the term can impose grim scenes. For example, some people may think of an impoverished Indian reservation as comparable to an underdeveloped country, and other people may think about a migrant labor camp with several families living in a one-room shanty with no access to safe drinking water or adequate sanitation.

Just as each city has its own unique features, it is also difficult to describe a “typical rural town” because of the wide population and geographic diversity. For example, rural towns in Florida, Oregon, Alaska, Hawaii, and Idaho are different from one another, and quite different from those in Vermont, Texas, Tennessee, Alabama, or California. Also, there can be vast differences between rural areas within one state. Still, descriptions and definitions for rural tend to be more subjective and relative in nature than those for urban (Cromartie, 2008).

For example, “small” communities with populations of more than 20,000 have some features that one may expect to find in a city. Then again, residents who live in a community with a population of less than 2000 may consider a community with a population of 5000 or 10,000 to be a city. Although some communities may seem geographically remote on a map, the residents who live there may not feel isolated. Those residents believe they are within easy reach of services through telecommunication and dependable transportation, although extensive shopping facilities may be 50 to 100 miles from the family home, obstetric care may be 150 miles away, or nursing services in the district health department in an adjacent county may be 75 or more miles away.

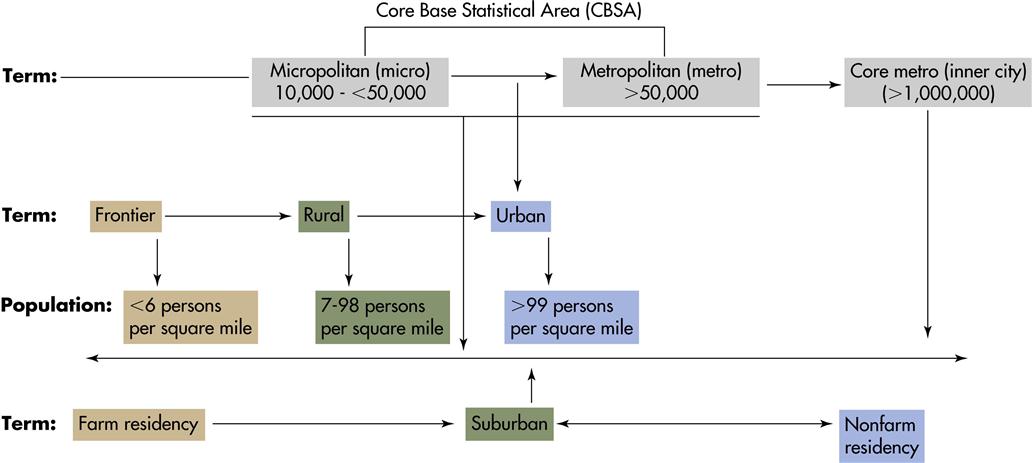

Rural-Urban Continuum

Frequently used definitions to describe rural and urban and to differentiate between them are provided by several federal agencies (Cromartie, 2008) (Box 19-1). These definitions, which in many cases are dichotomous in nature, fail to take into account the relative nature of ruralness. Rural and urban residencies are not opposing lifestyles. Rather, they must be seen as a rural-urban continuum ranging from living on a remote farm, to a village or small town, to a larger town or city, to a large metropolitan area with a core inner city (Figure 19-1).

Several federal agencies classify counties according to population density, specifically, metropolitan area (1090 U.S. counties), micropolitan area (674 U.S. counties), and non-core area (1378 U.S. counties) (USDA, 2006). The terms metropolitan and micropolitan statistical areas (metro and micro areas) refer to geographic entities primarily used for collecting, tabulating, and publishing Federal statistics. Core-Based Statistical Area (CBSA) is a collective term for both metro and micro areas. A metro area contains a core urban area of 50,000 or more population. A micro area contains an urban core of at least 10,000 (but less than 50,000) population. Each metro or micro area consists of one or more counties containing the core urban area. Likewise, adjacent counties have a high degree of social and economic integration (as measured by commuting to work) with its urban core (Cromartie, 2008).

Demographically, micro areas contain about 60% of the total non-metro population, with an average of 43,000 people per county. In contrast, non-core counties, with no urban cluster of 10,000 or more residents, have on average about 14,000 residents. In general, lack of an urban core and low overall population density may place these counties at a disadvantage in efforts to expand and diversify their economic base. The designation of micro areas is an important step in recognizing non-metro diversity. The term also provides a framework to understand population growth and economic restructuring in small towns and cities that have received less attention than metro areas. Nationally and regionally, many measures of health, health care use, and health care resources among rural populations vary by the level of urban influence in a particular region.

Micro areas embody a widely shared residential preference for a small-town lifestyle—an ideal compromise between large highly populated urban cities and sparsely populated rural settings. As information about these places makes its way into government data and publications alongside metro areas in the coming years, hopefully the notion of “micropolitan” will draw increased attention from policymakers and the business community.

In the past decade there has been a notable population shift from urban to less-populated regions of the United States. The fastest growing rural counties are located in rural regions of the nation and along the edges of larger metropolitan counties. Demographers metaphorically refer to this demographic phenomenon as the “doughnut effect.” That is to say, people are moving away from highly populated areas to outlying suburbs of urban centers. Most of the population growth has been in counties with a booming economy, with the geographic space to expand, and in western and southern states. Of the 10 fastest growing counties with 10,000 persons or more, 4 were located in western states, 5 in southern states, and 1 in a Midwestern state (Cromartie, 2008; USDA, 2005, 2006).

Clearly, a notable population shift will also affect the health status and lifestyle preferences of communities in which the shift occurs. As beliefs and values change over time, urban-rural differences narrow in some aspects and expand in others. Depending on the definition that is used, the actual rural population might vary slightly. According to Bureau of the Census estimates (2009), about 25% of all U.S. residents live in rural settings. In this chapter, rural refers to areas having fewer than 99 persons per square mile and communities having 20,000 or fewer inhabitants.

Current Perspectives

Population Characteristics

Adding to the confusion about what constitutes rural versus urban residency are the special needs of the numerous underrepresented groups (minorities, subgroups) who reside in the United States. In general, there are a higher proportion of whites in rural areas than in urban areas. There are, however, regional variations, and some rural counties have a significant number of minorities. Little is documented on the needs and health status of special rural populations (Mead et al, 2008; USDHHS, 2010b,c). Anthropologists are quick to report that, within a group, there often exists a wide range of lifestyles. Consequently, even in the smallest or most remote town or village, a subgroup may behave differently and have different values about health, illness, and patterns of accessing health care. Also, a group’s lifestyle may be associated with health problems that are different from those of the predominant cultural group in a given community. Background information on selected populations can be found in Chapters 7 and 32.

Demographically, rural communities include a higher proportion of younger and older residents. Nurses can expect to encounter more residents under the age of 18 and over 65 years of age in rural areas compared with an urban setting. Rural residents 18 years of age and older are more likely to be, or to have been, married than are their urban counterparts. As a group, rural adults are more likely to be widowed and have fewer years of formal education than urban adults (Cromartie, 2008; USDA, 2008a,b).

Although there are regional variations, rural families in general tend to be poorer than their urban counterparts. Comparing annual incomes with the standardized index established, more than one fourth of rural Americans live in or near poverty, and nearly 40% of all rural children are impoverished (Gamm et al, 2003; Rand Corporation, 2010a,b). Compared with those in metropolitan settings, a substantially smaller proportion of rural families are at the high end of the income scale. Accompanying the recent population shifts from urban to formerly rural areas, one can speculate that average income level might also change; however, no data are available at this time to substantiate this estimate. Regardless, level of income is a critical factor in whether a family has health insurance or qualifies for public insurance. Consequently rural families are less likely to have private insurance and more likely to receive public assistance or to be uninsured.

The working poor in rural areas are particularly at risk for being underinsured or uninsured. In working poor families, one or more of the adults are employed but still cannot afford private health insurance. Furthermore, their annual income is such that it disqualifies the family from obtaining public insurance. Several factors help explain why this phenomenon occurs more often in rural settings. For example, a high proportion of rural residents are self-employed in a family business, such as ranching or farming, or they work in small enterprises, such as a service station, restaurant, or grocery store. Also, an individual may be employed in part-time or in seasonal occupations, such as farm laborer and construction, in which health insurance often is not an employee benefit. In other situations, a family member may have a preexisting health condition that makes the cost of insurance prohibitive, if it is even available to them. At present it remains to be seen if this situation will change with the recent health care reform. A few rural families fall through the cracks and are unable to access any type of public assistance because of other deterrents, such as language barriers, compromised physical status, the geographic location of an agency, lack of transportation, or undocumented worker status. Insurance, or the lack of it, has serious implications for the overall health status of rural residents and the nurses who provide services to them (AHCPR, 2009; Bennett, Olatosi, and Probst, 2008; Nelson and Stover-Gingerich, 2010; USDHHS, 2010c).

Health Status of Rural Residents

Even though rural communities constitute about one fourth of the total population, the health problems and the health behaviors of the residents in them are not fully understood. This section summarizes what is known about the overall health status of rural adults and children. The health status measures that are addressed are perceived health status, diagnosed chronic conditions, physical limitations, frequency of seeking medical treatment, usual source of care, maternal-infant health, children’s health, mental health, minorities’ health, and environmental and occupational health risks (Bennett et al, 2008; Gamm et al, 2003; OSHA, 2010). Residents of rural areas suffer some of the same health problems as migrant farmworkers, as described in Chapter 34, including exposure to environmental factors and accidents.

Perceived Health Status

In general, people in rural areas have a poorer perception of their overall health and functional status than their urban counterparts. Rural residents over 18 years of age assess their health status less favorably than do urban residents. Studies show that rural adults are less likely to engage in preventive behavior, which ultimately increases exposure to risk. Specifically, they are more likely to use tobacco products and self-report higher rates of alcohol consumption and obesity; furthermore, they are less likely to engage in routine physical activity during leisure time, wear seat belts, have regular blood pressure checks, have Pap smears, complete breast self-examinations, and have colorectal screenings. Ultimately, failure to participate in health-promoting lifestyle behaviors affects the overall health status of rural residents, their level of function, physical limitations, degree of mobility, and level of self-care activities (American Legacy Foundation, 2009; Bennett et al, 2008; Gamm et al, 2003; NCHS, 2010; USDHHS, 2010b).

Chronic Illness

Rural adults are more likely than urban adults to have one or more of the following chronic conditions: heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, arthritis and rheumatism, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Nearly half of all rural adults have been diagnosed with at least one of these chronic conditions, compared with about one fourth of non-rural adults. Also, the prevalence of diagnosed diabetes in rural adults is about 7 out of 100 as opposed to 5 out of 100 in non-rural environments. Rural adults are more likely to have cancer (almost 7%) compared with urban adults (about 5%). Although most cases of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) are still found in urban areas, the rate is increasing in some rural populations (Bennett et al, 2008; Gamm et al, 2003; NCHS, 2010).

Rural-urban health disparities have been documented in health status (Box 19-2) and for health behaviors (Box 19-3). For example, there are disparities in the proportion of rural adults who receive medical treatment for both life-threatening illness, and degenerative or chronic conditions compared with urban adults. The proportion of rural residents who receive these treatments is high in rural versus urban areas. Life-threatening conditions include malignant neoplasms, heart disease, cardiovascular problems, and liver disorders. Degenerative or chronic diseases include diabetes, kidney disease, arthritis, and chronic diseases of the circulatory, nervous, respiratory, and digestive systems. In essence, chronic health conditions, coupled with their poor health status, limit the physical activities of a larger proportion of rural residents than of their urban counterparts (Bennett et al, 2008; Gamm et al, 2003; NCHS, 2010).

Physical Limitations

Limitations in mobility and self-care are strong indicators of an individual’s overall health status. Specific assessed measures on a national health survey included walking one block, walking uphill or climbing stairs, bending, lifting, stooping, feeding, dressing, bathing, and toileting. In fact, 9% of rural adults report at least three or more of these physical limitations, compared with 6% of metropolitan adults. The increased prevalence of poor health status and impaired function is not necessarily attributable to the increased number of older adults found in rural areas. Similar patterns are evident in adults 18 to 64 years of age. Rural adults under 65 years of age are more likely than urban adults to assess their health status as fair to poor, and a greater percentage have been diagnosed with a chronic health condition (Bennett et al, 2008; NCHS, 2010; USDHHS, 2010b).

Based on data from national health surveys, the overall health status of rural adults leaves much to be desired. This is attributed to a number of factors, including impaired access to health care providers and services, coupled with other rural factors. Thus nurses who practice in areas play an important role in providing a continuum of care to clients living in these underserved areas. Specifically, nurses can help clients have healthier lives by teaching them how to prevent accidents, engage in more healthful lifestyle behaviors, and reduce the risk of chronic health problems. Once clients in rural environments have been diagnosed with a long-term problem, nurses can help them manage chronic conditions to achieve better health outcomes and functioning (Nelson and Stover-Gingerich, 2010).

Patterns of Health Service Use

When the use of health care services is measured, it is found that more than three fourths of adults in rural areas received medical care on at least one occasion during a year. Despite their overall poorer health status and higher incidence of chronic health conditions, rural adults seek medical care less often than urban adults. In part, this discrepancy can be attributed to scarce resources and lack of providers in rural areas. Other reasons for this phenomenon are discussed later under Rural Health Care Delivery Issues and Barriers to Care (AHCPR, 2009; IOM, 2004; Cromartie, 2008; NACRHHS, 2008).

Availability and Access of Health Care

The ability of a person to identify a usual source of care is considered a favorable indicator of access to health care and a person’s overall health status. Essentially, a person who has a usual source of care is more likely to seek care when ill and adhere to prescribed regimens. Having the same provider of care can enhance continuity of care, as well as a client’s perception of the quality of that care. Rural adults are more likely than urban adults to identify a particular medical provider as their usual source of care. Rural adults are more likely to receive care from general practitioners and advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) compared to urban adults who are more likely to seek care from a medical specialist. However, this trend may be changing with health care reform, which emphasizes the importance of primary care (BHPR, 2007, 2009; USDHHS, 2010a,c).

Another measure of access to care is traveling time and/or distance to ambulatory care services. Rural persons who seek ambulatory care are more likely to travel more than 30 minutes to reach their usual source of care. Extended commuting time may also be a factor for residents in highly populated urban areas and those who must rely on public transportation. Once the person arrives at the clinic or physician’s office, no differences between rural and urban residents are found in the waiting time to see the provider.

In general there is a maldistribution of health professionals among rural and urban counties. For instance, 1 out of 17 rural counties is reported to have no physician. Among rural respondents on national surveys, the ability to identify a usual site of care or a particular provider often stems from a community or county having only one, perhaps two, health care providers. The limited number of health care facilities is reinforced by the finding that nearly all rural residents who seek health care use ambulatory services that are provided in a physician’s office as opposed to a clinic, community health center, hospital outpatient department, or emergency department (Gamm et al, 2003; IOM, 2004). One can speculate about the indicator of usual place and usual provider; that is to say, it suggests that rural residents are at least as well off as urban residents in regard to access to care (Woolston, 2010). However, this finding may be related to the fact that rural physicians tend to live and practice in a particular community for decades, thus providing care to multigenerational families who seek care from this particular provider.

Moreover, in a health professional shortage area (HPSA), a physician or a nurse practitioner may provides services to residents who live in surrounding counties. Or, one or two nurses in a county public health department usually offer a full range of services for all residents in a catchment area, which may span more than 100 miles from one end of a county to the other. Consequently, rural physicians and nurses frequently report, “I provide care to individuals and families with all kinds of conditions, in all stages of life, and across several generations.” It should not come as a surprise that rural respondents who participate in national surveys are able to identify a usual source and a usual provider of health care (BHPR, 2009; NCHS, 2010).

Maternal-Infant Health

Reports in the literature conflict regarding pregnancy outcomes in rural areas. Overall, rural populations have higher infant and maternal morbidity rates, especially counties designated as HPSAs, which often have a high proportion of racial minorities. Here one also finds fewer specialists, such as pediatricians, obstetricians, and gynecologists, to provide care to at-risk populations. There are extreme variations in pregnancy outcomes from one part of the country to another, and even within states. For example, in several counties located in the north-central and intermountain states, the pregnancy outcome is among the finest in the United States. However, in several other counties within those same states, the pregnancy outcome is among the worst. Particularly at risk are women who live on or near Indian reservations, are migrant workers, and are of African-American descent residing in rural areas in southeastern states (Mead et al, 2008; NCFH, 2010).

Public health nurses appreciate the interactive effects of socioeconomic factors, such as income level (poverty), education level, age, employment-unemployment patterns, and use of prenatal services, on pregnancy outcomes. There are other, less well-known health determinants, such as environmental hazards, occupational risks, and the cultural meaning placed on child-bearing and child-rearing practices by a community. The interaction effects of these multifaceted factors vary and often are difficult to measure.

Health of Children

Reports on the health status of rural children show regional variations and conflicting data. Comparing rural with urban children under 6 years of age on the measures of access to providers and use of services reveals the following (Bennett et al, 2008; Gamm et al, 2003):

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree