Perspectives in Global Health Care

Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to do the following:

2. Identify the health priorities of Health for All in the 21st Century (HFA21).

3. Analyze the role of nursing in global health.

4. Explain the role and focus of a population-based approach for global health.

5. Discuss the many causes of global health problems.

6. Identify some solutions for at least one of these global health problems.

11. Describe at least five organizations that are involved in global health.

Key Terms

bilateral organization, p. 74

determinants, p. 72

developed country, p. 68

disability-adjusted life-years, p. 81

environmental sanitation, p. 83

genocide, p. 91

global burden of disease, p. 81

health commodification, p. 77

Health for All in the 21st Century (HFA21), p. 67

Health for All by the Year 2000 (HFA2000), p. 67

lesser-developed country, p. 68

man-made disasters, p. 90

Millennium Development Goals, p. 69

multilateral organizations, p. 74

natural and man-made disasters, p. 82

non-governmental organization (NGO), p. 74

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), p. 75

philanthropic organizations, p. 77

population health, p. 72

primary health care, p. 72

private voluntary organization (PVO), p. 74

religious organizations, p. 76

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), p. 75

World Bank, p. 76

World Health Organization (WHO), p. 74

—See Glossary for definitions

Anita Hunter, PhD, APRN–CPNP, FAAN∗

Anita Hunter, PhD, APRN–CPNP, FAAN∗

Dr. Anita Hunter has been a pediatric nurse practitioner since 1975, working with the vulnerable populations of children and families living in poor urban and rural communities. Her work with culturally diverse populations expanded to the international arena in 1994 when she began taking students and faculty on clinical immersion experiences. These immersion medical missions have extended into Northern Ireland, Ghana, Mexico, the Dominican Republic, and Uganda; each evolving into sustainable health initiatives within each country. In conjunction with her prior academic role as Director of MSN Programs and the International Nursing Office at the University of San Diego, Dr. Hunter also serves as the Medical Director for the Holy Innocents Children’s Hospital Uganda NGO (non-governmental organization) that oversees the development and management of the Holy Innocents Children’s Hospital in Uganda. Dr. Hunter is the Chairperson, Department of Nursing at Dominican University of California.

This chapter presents an overview of the major public health problems of the world, along with a description of the role and involvement of nurses in global and community health care settings. It describes health care delivery from a global and population health perspective, illustrates how health systems operate in different countries, presents examples of organizations that address global health, and explains how economic development relates to health care throughout the world.

Overview and Historical Perspective of Global Health

Why is it important for nurses to understand and attend to global health issues? Why be concerned about population health at the global level? What is a nurse’s responsibility to global health? Such questions have been asked of this author over the last 15 years while working in the global arena. Her response is framed by the following: philosophically, we should be global citizens, caring about and for the greater than 80% of the world that is impoverished, starving, and dying from preventable conditions. What once were the unique health challenges of people in less-developed countries, such as loss of human rights, lack of access to food, housing, safety, and health care, are now common problems of people all over the world. Global warming, destruction of natural resources, increasing global violence, the declining global economy, and the depletion of food supplies all contribute to the current global health crisis. Preventable conditions like malaria, malnutrition, communicable diseases, chronic health problems, and conditions related to environmental pollution are taxing the health care systems of many nations. Immigrants from developing nations often bring these conditions with them. Understanding global health and factors that contribute to the immigrant’s health problems better prepares the nurse to develop interventions that are culturally congruent, culturally responsive, and culturally acceptable to the people for whom interventions are planned.

Nursing has been actively engaged in global health (Lewis, 2005) since the turn of the twentieth century, as nurses served in each of the World Wars, Korea, Vietnam, and the wars of the twenty-first century, striving to save the lives of combatants and non-combatants. Dealing with the collateral damage of war, nurses became committed to help intervene before wars began with the intent that addressing the factors that contributed to war might change the outcome and prevent it. In 1977 attendees at the annual meeting of the World Health Assembly stated that all citizens of the world should enjoy a level of health that would permit them to lead a socially and economically productive life. This goal was to have been achieved by the year 2000; however, man-made and natural disasters, political corruption, lack of infrastructures in lesser-developed nations, and unforeseen obstacles have inhibited this goal from being achieved. The goals of Health for All by the Year 2000 (HFA2000) were extended into the next century with the document Health for All in the 21st Century (HFA21). These goals have continued to be promoted by numerous health-related conferences held around the world, including the International Council of Nurses (ICN). Therefore, nurses must be globally astute and involved in helping to ensure that these goals are obtained by the people of the world.

In 1978 concern for the health of the world’s people was voiced at the International Conference on Primary Health Care that was held in Alma Ata, Kazakhstan, in what was then Soviet Central Asia. The conference, sponsored by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), had representatives from 143 countries and 67 organizations. They adopted a resolution that proclaimed that the major key to attaining HFA2000 was the worldwide implementation of primary health care (Lucas, 1998). These global partners continue to evolve the Healthy People doctrine. The third iteration of Healthy People entitled Healthy People 2020 was released in December 2010.

Since the Alma Ata conference, there has been growing interest in global health and how best to attain it. People around the world want to know and understand the issues and concerns that affect health on a global scale. This is important since many countries have not yet experienced the technological advancement in their health care systems that have been realized by more developmentally advanced countries. Many terms are used to describe nations that have achieved a high level of industrial and technological advancement (along with a stable market economy) and those that have not. For the purposes of this chapter, the term developed country refers to those countries with a stable economy and a wide range of industrial and technological development (e.g., the United States, Canada, Japan, the United Kingdom, Sweden, France, and Australia). A country that is not yet stable with respect to its economy and technological development is referred to as a lesser-developed country (e.g., Bangladesh, Zaire, Haiti, Guatemala, most countries in sub-Saharan Africa, and the island nation of Indonesia). Both developed and lesser-developed countries are found in all parts of the world and in all geographic and climatic zones.

Health problems exist throughout the world, but the lesser-developed countries often have more exotic sounding health care problems such as Buruli ulcers, leishmaniasis, schistosomiasis, brucellosis, typhus, yellow fever, and malaria (WHO, 2000a). Ongoing health problems needing control in lesser-developed countries include measles, mumps, rubella, and polio; the current health concerns of the more-developed countries are problems such as hepatitis, infectious diseases, and new viral strains such as the hantavirus, SARS, H1N1, and avian flu. Chronic health problems such as hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, cancer, the resurgence of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) among adolescents and young adults, drug-resistant tuberculosis (TB); and the larger social, yet health-related, issues such as terrorism, warfare, violence, and substance abuse are now global issues (ICN, 2003). World travelers both serve as hosts to various types of disease agents and may expose themselves to diseases and environmental health hazards that are unknown or rare in their home country. Two examples of diseases from recent years that were once fairly isolated and rare but are now widespread throughout the world are AIDS and drug-resistant TB (IOM, 2009, 2010; WHO, 2004a) (Figure 4-1).

In addition to direct health problems, increasing populations, migration within countries, political corruption, lack of natural resources, and natural disasters affect the health and well-being of populations. Dr. Paul Farmer (2005) talks about the war on the poor; how many migrate to the city to find employment where limited employment opportunities exist. Such migration leads to the development of shanty towns often built on the outskirts of cities, on unstable ground, and in areas vulnerable to natural disasters such as hurricanes, tsunamis, and earthquakes such as those in Haiti, Chile, and Indonesia. These environments are unsanitary, unsafe, and a breeding ground for TB, dysentery, malnutrition, abuse of women and children, and mosquito and other insect or animal-borne diseases.

Nations plagued by civil war and political corruption are faced with chronic poverty, unstable leadership, and lack of economic development. The effects of war and conflict also have devastating effects on a country and the health of its population. The wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, and the West Bank of Palestine, to name a few, have had devastating mental and physical health consequences, leaving each country and its people with few health care services or other resources to sustain life. A recent research study about the long-term effects of children exposed to war (Asia, 2009) supports the negative health consequences of such exposure. For example, changes in biomarkers can lead to future chronic health conditions like cardiovascular disease, autoimmune conditions, cancer, and mental health problems. Serious nutritional problems and outbreaks of influenza have been reported. The increased incidence of violence against women and children, the hazards of unexploded weapons and land mines, and the occurrence of earthquakes and other natural disasters increase the health risks (USAID, 2005; WHO, 2002a,b).

As countries promote the objectives of HFA21, they realize that they need to improve their economies and infrastructures. They often seek funds and technological expertise from the wealthier and more-developed countries (UN, 2009; World Bank, 2005). According to the WHO, HFA21 is not a single, finite goal but a strategic process that can lead to progressive improvement in the health of people (WHO, 2002c). In essence, it is a call for social justice and solidarity. Unfortunately, the lesser-developed nations lack the infrastructure necessary to achieve health promotion and living conditions, as many of these countries continue to deteriorate for the poor, and environments that breed infections are the norm (Figure 4-2).

The United Nations’ (UNs’) Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were first agreed upon by world leaders at the Millennium Summit in 2000 (see Resource Tool 3.A on the book’s Evolve site). The MDGs were developed to relieve poor health conditions around the world and to establish positive steps to improve living conditions (UN, 2005). By the year 2005, all member nations pledged to meet the goals described in Box 4-1. These goals have continued to evolve as natural disasters and internal strife continue to affect the poor and the vulnerable. The Millennium Report (UN Millennium Development Report, 2009) describes the developed nations’ responsibility to the betterment of those in lesser-developed nations. The revised goals highlight the global responsibility to eradicate poverty and hunger; achieve universal primary education for all children; promote gender equality and empower women; reduce child mortality; improve maternal health; combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases; ensure environmental sustainability; and develop a global partnership for development. The U.S. has supported this mandate in its Global Health Initiatives (n.d.) as has the ICN. As economic agreements between countries remove financial and political barriers, growth and development are stimulated. Simultaneously, as global health problems that once seemed distant are brought closer to people around the globe, political and economic barriers between countries fall.

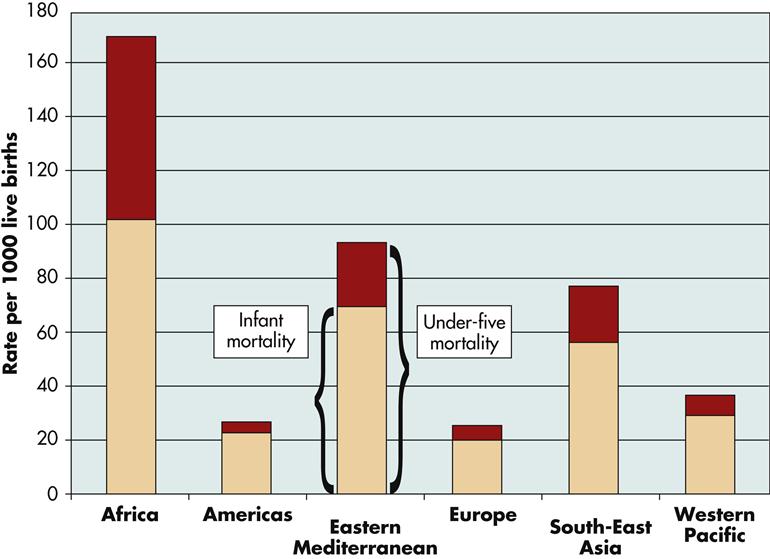

Despite efforts by individual governments and international organizations to improve the general economy and welfare of all countries, many health problems continue to exist, especially among poorer people. Many countries lack both political commitment to health care and recognition of basic human rights. They may fail to achieve equity in access to primary health care, demonstrate inappropriate use and allocation of resources for high-cost technology, and maintain a low status of women. Currently, the lesser-developed countries experience high infant and child death rates (Figure 4-3), with diarrheal and respiratory diseases as major contributory factors (WHO, 2010).

Other major worldwide health problems include nutritional deficiencies in all age groups, women’s health and fertility problems, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), and illnesses related to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), malaria, drug-resistant TB, neonatal tetanus, leprosy, occupational and environmental health hazards, and abuses of tobacco, alcohol, and drugs. Because of these continuing problems, the Director General of the WHO has made a commitment to renew all of the policies and actions of HFA21. The WHO continues to develop new and holistic health policies that are based on the concepts of equity and solidarity with an emphasis on the individual’s, family’s, and community’s responsibility for health. Strategies for achieving the continuing goals of HFA21 include building on past accomplishments and the identification of global priorities and targets for the first 20 years of the new century (WHO, 2002).

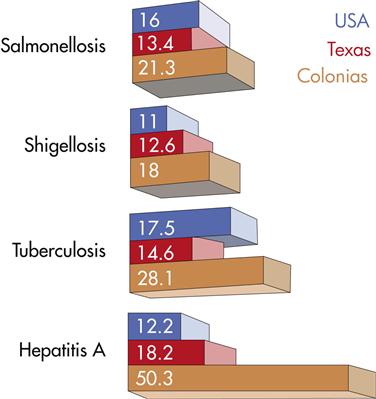

Nurses need to be informed about global health. Many of the world’s health problems directly affect the health of individuals who live in the United States. For example, the 103rd U.S. Congress passed the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which opened trade borders between the United States, Canada, and Mexico in 1994 and allowed an increased movement of products and people. Along the United States–Mexico border, an influx of undocumented immigrants in recent years has raised concerns for the health of people who live in this area. For example, many immigrants have settled on unincorporated land, known as colonias, outside the major metropolitan areas in California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. These colonies may have no developed roads, transportation, water, or electrical services (Figures 4-4 and 4-5).

Conditions in these settlements have led to an increase in disease conditions such as amebiasis and respiratory and diarrheal diseases. Environmental health hazards in the colonias are associated with poverty, poor sanitation, and overcrowded conditions (Brown, 2005). On a more positive note, NAFTA has provided an impetus and framework for the government of Mexico to modernize their medical system so that they can compete and respond to the demands of more global competition. Although some improvements have been made, there is still an overriding concern that environmental and health regulations in Mexico have not kept up with the pace of increased border trade (Malkin, 2009). The Mexican National Academy of Medicine continues to make health and environmental recommendations to the government, which illustrates the beneficial interactions that are occurring between Mexico, Canada, and the United States as part of this trade agreement. Nurses play a significant role in obtaining health for the indigent and undocumented persons who live along the border regions in Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California. Nurses supported by private foundations and by local and state public health departments often provide the only reliable health care in these areas.

Interestingly, Canadian worker groups were concerned that NAFTA would eventually lead to worsened working conditions as manufacturing plants move to the lower-wage and largely non-unionized southern United States and Mexico (Fuller, 2002); however, reports indicate that trade, standard of living, and employment opportunities have risen (Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada International, 2009; Cahoon and Myles, 2004).

The Role of Population Health

Population health refers to the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group, and includes health outcomes, patterns of health determinants, and policies and interventions that link these two (Kindig and Stoddard, 2010). It is an approach and perspective that focuses on the broad range of factors and conditions that have a strong influence on the health of populations (environment, genetics, ethnicity, pollution, and physical and mental stressors affecting a community). Using epidemiological trends, population health emphasizes health for groups at the population level rather than at the individual level and focuses on reducing inequities, improving health in these groups to reduce morbidity and mortality, and assessing emerging diseases and other health risks to a community (IOM, 2002). A population can be defined by a geographic boundary, by the common characteristics shared by a group of people such as ethnicity or religion, or by the epidemiological and social conditions of a community (Fox, 2001).

The factors and conditions that are important considerations in population health are called determinants. Population health determinants may include income and social factors, social support networks, education, employment, working and living conditions, physical environments, social environments, biology and genetic endowment, personal health practices, coping skills, healthy child development, health services, sex, and culture (Galea, 2008; Ibrahim et al, 2001). The determinants do not work independently of each other but form a complex system of interactions.

Canada is a leader in promoting the population health approach. Canada has been implementing programs using this framework since the mid-1990s and builds on a tradition of public health and health promotion. Box 4-2 presents the development of the Healthy Cities movement in Toronto. A Canadian document, the Lalonde Report (1974), proposed that changes in lifestyles or social and physical environments lead to more improvements in health than would be achieved by spending more money on existing health care delivery systems. The Canadian initiative was aimed at efforts and investments directed at root causes to increase potential benefits for health outcomes (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2005). A key was the identification and definition of health issues and of the investment decisions within a population that were guided by evidence about what keeps people healthy. Therefore a population health approach directs investments that have the greatest potential to influence the health of that population in a positive manner. Canada has since implemented a broad range of projects across the country and is a model that many U.S. communities have begun to adopt. The 2002 IOM report emphasized the need to assess the determinants affecting population health and initiate interventions to correct them because America’s health status did not match the country’s substantive investment in health (IOM, 2002).

International communities have also integrated the health determinants into public policies. At the 2009 Nairobi Global Conference on Health Promotion, over 600 participants representing 100 countries adopted a Call to Action on addressing population health and finding ways to promote health at the global level. Health and development today face unprecedented threats by the financial crisis, global warming and climate change, and security threats. Since 1986, with the development of the first Global Conference, until 2009, a large body of evidence and experience has accumulated about the importance of health promotion as an integrative, cost-effective strategy, and as an essential component of health systems primed to respond adequately to emerging concerns (WHO, 2010).

As nurses work with immigrants from global arenas or become active participants in health care around the world, understanding such concepts as population health and the determinants of health for a population becomes more important than the most advanced acute care skills. These skills, though important, are intended to help an individual; population health skills sets can help the world.

Primary Health Care

The role of primary health care is historically based on the worldwide conference that was held at Alma Ata (Tejada de Rivers, 2003). WHO and UNICEF still actively promote primary health care and maintain that the training of health workers needs to be based on current primary health care practices. They advocate for community members to be involved in all aspects of the planning and implementation of health services that are delivered to their respective communities.

The early recommendations in 1978 by WHO/UNICEF believed that a unified approach to creating primary care services globally was important. These aims continue to be reinforced and modified and were recently updated to incorporate MDGs (WHO, 2003a; Kekki, 2005). Such services included the following:

• Aggressive attention to environmental sanitation, especially food and water sources

• Development of maternal and child health programs that include immunization and family planning

• Accessibility and affordability of services for the treatment of common diseases and injuries

• Development of nutrition programs

Global leaders have recognized the need to get nations committed to the health care agenda (the UNs’ MDGs, 2009). Maeseneer et al (2008) presented 12 characteristics that define primary health care: it is general in scope, accessible, integrated (including health promotion, disease prevention, cure and care, rehabilitation and palliation), continuous, dependent on teamwork, holistic, personal (focusing on the person rather than the disease), family and community oriented, coordinated, confidential (respecting the client’s privacy), and playing an advocacy role. An important effort is needed at the level of recruitment, education, and retention of primary health care workers, including primary care nurses, family physicians, and mid-level care workers. Professional organizations, clinical agencies, universities, and other institutions for higher education should continue to demonstrate their “social accountability” by training appropriate providers.

Mexico is an example of a country that has made a particular effort to implement primary health care services. Mexico has initiated a module program that is administered through the ministry of health. The program is characterized by village-based health posts, each of which is operated by a community volunteer and a health committee. The volunteer and committee are supervised by a nurse who operates from a regional health center. It is believed that this module system can address community needs and will ultimately lead to better use of services and resources (Nigenda, Ruiz, and Montes, 2001).

Nursing and Global Health

Nurses play a leadership role in health care throughout the world (Hancock, 2005). Those with public health experience provide knowledge and skill in countries where nursing is not an organized profession, and they give guidance to the nurses as well as to the auxiliary personnel who are part of the primary health care team (ICN, 2001a). In many areas in the developed world, nurses provide direct client care and help meet the education and health promotion needs of the community. They are viewed as strong advocates for primary health care, through social commitment to equality of health care and support of the concepts that are contained in the Alma Ata declaration (ICN, 2003).

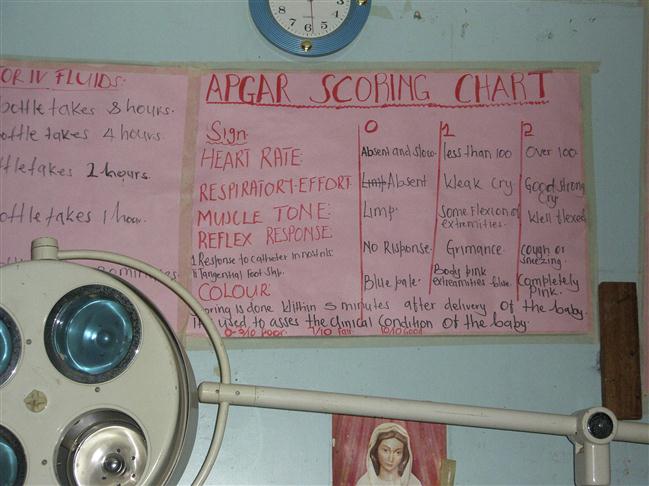

Unfortunately, in the lesser-developed countries, the role of the nurse is defined poorly, if at all, and care often depends on and is directed by physicians (Buchan and Dal Poz, 2002). This author has seen health care systems in Africa, Mexico, and the Dominican Republic in which nursing is not valued and the ability of nurses to contribute to improving an individual’s health, much less a community’s health, is minimal. Much work is needed to raise the bar in the education of nurses in these countries so they have the skills necessary to make a difference; however, overcoming some of the cultural and gender-role barriers makes this process laborious (Figure 4-6).

Nurses have led in care delivery in such areas as the devastating tsunami in south Asia (ICN, 2005), and more recently after the earthquakes in Haiti and Chile in 2010. Other health interventions have been the interprofessional work of nursing and science to build and open the dedicated children’s hospital in Uganda (Bolender and Hunter, 2010), the nurse-developed Ghana Health Mission (Hunter and McKenry, 2005), a quality improvement program in the Congo (DuMortier and Arpagaus, 2005), an emergency service program in Mongolia (Cherian et al, 2004), and a community-based TB program in Swaziland (Escott and Walley, 2005).

On a different continent, the role of nursing in China and Taiwan is noteworthy. Nursing in China is undergoing a dramatic change, largely because of an evolving political and economic environment. In the past, nursing was viewed as a trade, and the acquisition of nursing skills and knowledge took place in the equivalent of a middle school or junior high in the United States. Increasing pressure on the health care system in China is providing an impetus for education at the university level. The Chinese government has sent many nurses to the United States, Europe, and Australia to receive university-level education in nursing at the undergraduate and graduate levels in hopes that these individuals will return to China to provide the nursing and nursing education needed there (Anders and Harrigan, 2002). The author, in conjunction with a colleague (Dr. Mary Jo Clark), has consulted in Taiwan, helping them establish their nurse practitioner programs and to implement their doctoral programs in nursing. Part of that consultation involved the use of standardized clients as a component for certification and license to practice as a nurse practitioner. The United States is just beginning to entertain this idea.

In some countries, such as Chile, the physician-to-population ratio is higher than the nurse-to-population ratio. In these cases, physicians influence nursing practice and place economic and political pressure on local, regional, and national governments to control the services that nurses provide. In Chile, nurses have set up successful and cost-effective clinics to deliver quality primary care services, but they are constantly being threatened by physicians who want to remove the nurses and replace them with the more costly services of physicians (WHO, 2000a). Box 4-3 describes nursing and health care efforts in Zambia.

Major Global Health Organizations

Many international organizations have an ongoing interest in global health. Despite the presence of these well-meaning organizations, it is estimated that the lesser-developed countries still bear most of the cost for their own health care and that contributions from major international organizations actually provide for less than 5% of needed costs. Recent reports indicate that the majority of funds raised by international organizations are used for food relief, worker training, and disaster relief (IMVA, 2002). However, when considering the total effort, the poorer countries, such as those in sub-Saharan Africa, still receive the greatest amount of financial support from the more developed countries, often accounting for more than 20% of the poorer country’s health care expenditures (IMVA, 2002; World Bank, 2005).

International health organizations are classified as multilateral organizations, bilateral organizations, or non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or private voluntary organizations (PVOs) (including philanthropic organizations). Multilateral organizations are those that receive funding from multiple government and non-government sources. The major organizations are part of the United Nations (UN), and they include the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), and the World Bank. A bilateral organization is a single government agency that provides aid to lesser-developed countries, such as the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). NGOs or PVOs, including the philanthropic organizations, are represented by such agencies as Oxfam, Project Hope, the International Red Cross, various professional and trade organizations, Catholic Relief Services (CRS), church-sponsored health care missionaries, and many other private groups.

Specifically, the World Health Organization (WHO) is a separate, autonomous organization that, by special agreement, works with the UN through its Economic and Social Council. The idea for this worldwide health organization developed from the First International Sanitary Conference in 1902, a precursor to the WHO (Campana, 2005). The WHO was created in 1946 as an outgrowth of the League of Nations and the UN charter that provided for the formation of a special health agency to address the wide scope and nature of the world’s health problems. The WHO, headed by a director general and five assistant generals, has three major divisions: (1) the World Health Assembly approves the budget and makes decisions about health policies, (2) the executive board serves as the liaison between the assembly and the secretariat, and (3) the secretariat carries out the day-to-day activities of the WHO. The principal work of the WHO is to direct and coordinate international health activities and to provide technical medical assistance to countries in need. More than 1000 health-related projects are ongoing within the WHO at any one time. Requests for assistance may be made directly to the WHO by a country for a project, or the project may be part of a larger collaborative endeavor involving many countries. Examples of current collaborative, multinational projects include comprehensive family planning programs in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand; applied research on communicable disease and immunization in several East African nations; and projects that investigate the viability of administering AIDS vaccines to pregnant women in South Africa and Namibia. For further information about the WHO, visit http://www.who.int/en/online.

Another multilateral agency is the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) (http://www.unicef.org). Formed shortly after World War II (WWII) to assist children in the war-ravaged countries of Europe, it is a subsidiary agency to the UN Economic and Social Council. After WWII, many social agencies realized that the world’s children needed medical and other kinds of support. With financial assistance from the newly formed UN General Assembly, post-WWII programs were developed to control yaws, leprosy, and TB in children. Since then, UNICEF has worked closely with the WHO as an advocate for the health needs of women and children under the age of 5. In particular, there have been multinational programs aimed at the provision of safe drinking water, sanitation, education, and maternal and child health.

The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) is one of the oldest continuously functioning multilateral agencies, founded in 1902, and predates the WHO. Presently, PAHO serves as a regional field office for the WHO in Latin America, with a focused effort to improve the health and living standards of the Latin American countries. PAHO distributes epidemiological information, provides technical assistance over a wide range of health and environmental issues, supports health care fellowships, and promotes health and environmentally related research, along with professional education. Focusing primarily on reaching people through their communities, PAHO works with a variety of governmental and non-governmental entities to address the health issues of the people of the Americas. At present, a primary concern of PAHO is the prevention and control of AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases amongst the most vulnerable: mothers and children, workers, the poor, older adults, refugees, and displaced persons. With the earthquakes in Haiti and Chile, and the drought and starvation in Guatemala, PAHO’s attentions are being directed toward crisis intervention (http://new.paho.org/hq). Other focused efforts include the provision of public information, the control and eradication of tropical diseases, and the development of health system infrastructures in the poorer Latin American countries. PAHO collaborates with individual countries and actively promotes multinational efforts as well. Recently PAHO has examined the effects of health care reform on nurses and midwifery in the Latin American countries and found that the reform changed the work environments, the scope of practice, and the relationship of nurses with other health care workers and providers. The role of PAHO in the development of healthy communities is discussed in Chapter 20.

The World Bank (http://www.worldbank.org) is another multilateral agency that is related to the UN. Although the major aim of the World Bank is to lend money to the lesser-developed countries so that they might use it to improve the health status of their people, it has collaborated with the field offices of the WHO for various health-related projects such as the control and eradication of the tropical disease onchocerciasis in West Africa, as well as programs aimed at providing safe drinking water and affordable housing, developing sanitation systems, and encouraging family planning and childhood immunizations. The World Bank also sponsors programs to protect the environment, as reflected by the $30 million project in Brazil to protect the Amazon ecosystem and reduce the effects on the ozone layer; to support people in lesser-developed countries to pursue careers in health care; and to improve internal infrastructures, including communication systems, roads, and electricity, all of which ultimately affect health care delivery.

Bilateral agencies operate within a single country and focus on providing direct aid to lesser-developed countries. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) (http://www.usaid.gov) is the largest of these and supports long-term and equitable economic growth and advances U.S. foreign policy objectives by supporting economic growth, agriculture, and trade; global health; and democracy, conflict prevention, and humanitarian assistance. It provides assistance in five regions of the world: Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, Europe and Eurasia, and the Middle East. All bilateral organizations are influenced by political and historical agendas that determine which countries receive aid. Incentives for engaging in formal arrangements may include economic enhancements for the benefit of both countries, national defense of one or both countries, or the enhancement and protection of private investments made by individuals in these nations. Something similar is present in other developed nations around the globe. For example, the Japanese government currently has an active collaborative arrangement with Indonesia to study ways to control the spread of yellow fever and malaria. France gives most of its aid to its former colonies.

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or private voluntary organizations (PVOs), as well as philanthropic organizations, provide almost 20% of all external aid to lesser-developed countries. NGOs and PVOs are represented by many different kinds of religious and secular groups. Representatives of these independent citizen organizations are increasingly active in policy-making at the United Nations. These organizations are often the most effective voices for the concerns of ordinary people in the international arena. NGOs include the most outspoken advocates of human rights, the environment, social programs, women’s rights and more (Global Policy Forum, 2010). The author is the Medical Director for the Holy Innocents Children’s Hospital Uganda NGO (www.holyinnocentsuganda.org) founded in San Diego, CA in 2007. Its mission was to build the first dedicated children’s hospital in Uganda in order to address the unnecessary loss of lives of children from preventable conditions, especially malaria. In its first year of operation, the hospital with its 53 beds and an outpatient department has cared for over 16,000 children and become the regional “NICU” and a pediatric “tertiary” setting.

The International Red Cross (http://www.icrc.org) is one of the best-known NGOs. Although the Red Cross is most often associated with disaster relief and emergency aid, it lays the groundwork for health intervention as a result of a country’s emergency. It is a volunteer organization that consists of approximately 160 individual Red Cross societies around the world, and it prides itself on its neutrality and impartiality with respect to politics and history. Therefore, it seeks permission from the country in which the disaster occurs before services are rendered.

Another NGO that provides health services and aid to countries experiencing warfare or disaster is Medicins San Frontieres (MSF) (http://www.msf.org), also home of Doctors without Borders. It is an international, independent, medical humanitarian organization that delivers emergency aid to people affected by armed conflicts, epidemics, health care exclusion, and natural or man-made disasters. Unlike the Red Cross, MSF does not seek government approval to enter a country and provide aid and it often speaks out against observed human rights abuses in the country it serves. MSF was the recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1999 and the Conrad Hilton Prize in 1998.

The professional and trade organizations are PVOs that are found mostly in the more developed and industrialized countries. One of the most famous of the professional and technical organizations is the Institut Pasteur, which began in the 1880s. Its laboratories have facilitated the development of sera and vaccines for countries in need, have disseminated current health information, and have trained and provided fellowships for medical training and study in France.

Religious organizations, reflecting several denominations and religious interests, support many health care programs, including hospitals in rural and urban areas, refugee centers, orphanages, and leprosy treatment centers. For example, the Maryknoll Missionaries, sponsored by the Roman Catholic Church, carry out health service projects around the world. The missionaries comprise a large group of religious as well as lay people trained and educated in a variety of educational and health care professions. The Catholic Relief Services (CRS) (http://crs.org) is the official international humanitarian agency of the Catholic community in the United States. CRS alleviates suffering and provides assistance to people in need who are affected by war, starvation, famine, drought, and natural disasters, in more than 100 countries, without regard to race, religion, or nationality. Many Protestant and evangelical groups throughout the world function both as separate entities and as part of the Church World Service, which works jointly with secular organizations to improve health care, community development, and other needed projects. Other private and voluntary groups that assist with the worldwide health effort include CARE (http://www.care.org), Oxfam (www.oxfam.org.uk), and Third World First. Several of these organizations receive additional funding from developed countries including the United States, the United Kingdom, Sweden, Canada, and countries in Western Europe.

Philanthropic organizations receive funding from private endowment funds. A few of the more active philanthropic organizations that are involved in world health care include the W. K. Kellogg Foundation, the Milbank Memorial Fund, the Pathfinder Fund, the Hewlett Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Carnegie Foundation, and the Gates Foundation. The purpose and programmatic goals of each organization differ widely with respect to funding, and their purposes often change as their governing boards change. Some of the worldwide health care activities that have been sponsored in the past include projects in public and preventive health; vital statistics; medical, nursing, and dental education; family planning programs; economic planning and development; and the formation of laboratories to investigate communicable diseases.

Many private and commercial organizations such as Nestle and the Johnson & Johnson Company provide financial and technical backing for investment, employment, and access to market economies and to health care. Although these organizations have been present throughout the world for more than 30 years, they have come under criticism for the promotion and marketing of infant formulas, pharmaceuticals, and medical supplies, especially to lesser-developed countries. The intense marketing that is done in these countries is known as commodification, turning health care into a business with clients as consumers and health care professionals from altruistic healers to business technicians (Lown, 2007; White, Henderson, and Petersen, 2002). There is global controversy as to the legitimacy of commodification. For example, the health commodification of pharmaceuticals in southern India is a concern because the companies give little consideration to the cultural and social structure of the country, thus interfering with the long-standing traditional Indian medical system. In southern India, good health and prosperity are related to certain social parameters bestowed to families and communities as a result of their conformity to the socio-moral order that was established by their ancestors, gods, and patron spirits (Segal, Demos, and Kronenfeld, 2003). The taking of pharmaceutical agents thus disrupts the social and cultural order of things that have been traditionally addressed by cultural practices. Similar controversies in other countries have involved infant formulas and oral rehydration therapies.

Global Health and Global Development

Global health is not just a global public health agenda; it does not begin and end with the individual; it must consider all factors within a country that affect health, such as environment, education, national and local policies, health care and access to health care, economics (importing and exporting of goods, industry, technology), war, and public safety. This paradigm shift is called global health diplomacy, which refers to multilevel and multifactor negotiation processes involving environment, health, emerging diseases, and human safety. It is now recognized that to solve global health problems, one must build capacity for global health diplomacy by training public health professionals and diplomats respectively to prevent the imbalances that emerge between foreign policy and public health experts and the imbalances that exist in negotiating power and capacity between developed and developing nations (Kickbusch, Silberschmidt, and Buss, 2007). The cutting edge of global health diplomacy raises certain cautions regarding health’s role in trade and foreign policies. Unfortunately, securing health’s fullest participation in foreign policy does not ensure health for all, but it supports the principle that foreign policy achievements by any country in promoting and protecting health will be of value to all (Drager and Fidler, 2007).

Nurses cannot think in isolation about health for the global population; they must think more broadly to achieve their goals through a multidiscipline and multilevel approach involving such dimensions as economic, industrial, and technological development. An example of this global health diplomacy approach, developed by the author and her colleagues, is the Uganda Project. What began as a simple request to help a community in Uganda save the lives of children dying unnecessarily from preventable diseases has turned into a sustainable community development project. Serving as consultants to an NGO, led by the school of nursing at the University of San Diego, and working collaboratively with the departments of environmental science and business, students and faculty have provided volunteer service and consultation to the people of Mbarara, Uganda on the building, implementation, and sustainability of a children’s hospital in their community. Such consultation involved addressing the training of health care professionals on pediatric care and lay health educators to help improve the health of the community; assessing and intervening on water quality issues affecting public health; and assessing and making recommendations for business ventures that could help support the fiscal sustainability of the hospital and improve the economics of the community. Future projects will include faculty and students from the school of peace studies to help the community learn how to deal with conflict and social justice issues and the school of education to help support the teacher training that might better serve the education of the children (Bolender and Hunter, 2010).

Access to services and the removal of financial barriers alone do not account for use of health services. In fact, the introduction of health care technology from developed countries to lesser-developed countries has led to less-than-satisfactory results. For example, during the 1980s in an eastern Mediterranean country, two thirds of the high-output x-ray machines were not in use because of a lack of qualified and trained individuals to carry out routine maintenance and repairs (World Bank, 2005). In another example, a hospital in a Latin American country was given a high-technology neonatal intensive care unit by a wealthier and more technologically advanced country. However, 70% of the infants died after discharge because there were no follow-up nutritional and prevention services, and many of them experienced malnutrition and complications from dehydration on return to their home communities. Countries devastated by war have lost their total infrastructures for food, trade, social justice, health, water, and public security as evident today in Afghanistan, the West Bank, Gaza, Darfur, and other war-torn countries. When implementing services for lesser-developed nations, it is essential to conduct needs assessments to learn what a community has, what a community wants, and what it can sustain. Quite simply, the aforementioned projects, although well-intended, failed because the most basic needs were not met, nor was recognition given to what resources and services the country could sustain.

On the basis of these examples, improvement in the overall health status of a population contributes to the economic growth of a country in several ways (World Bank, 2005; WHO, 2009):

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree