Elizabeth A. Ayello, PhD, RN, ACNS-BC, CWON, MAPWCA, FAAN

Kevin Y. Woo, PhD, RN, FAPWCA, IIWCC-CAN

R. Gary Sibbald, BSc, MD, MEd, FRCPC (Med Derm), MACP, FAAD, MAPWCA

Objectives

After completing this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- define and identify the components of wound-associated pain

- describe the similarities and differences of pain associated with various types of chronic wounds

- utilize two validated patient tools for chronic wound-related pain

- assess the advantages and disadvantages of wound pain treatment modalities.

Etiology and Definitions of Pain

Pain has an element of blank;

It cannot recollect

When it began, or if there were

A day when it was not.

—EMILY DICKINSON

As clinicians, we have a tendency to identify various wound types as having characteristic pain of a specific type or amount. However, pain is what the patient states it is—not what we believe it to be. Our responsibility as clinicians is to assess the patient’s pain accurately and treat it adequately, without judging the patient or doubting that the pain is as described. Pain is often more important to patients than it is to clinicians, with surveys indicating that pain is the most important parameter for many patients but is often only the third or fourth priority for clinicians.

There are several definitions of pain in the literature. Both the 1979 International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) Subcommittee on Taxonomy1 and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ, formerly the Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research, or AHCPR)2 support a common definition of pain. They have defined pain as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage.1,2

Another commonly used pain definition is that of McCaffery and colleagues, 3,4 who state that “pain is whatever the experiencing person says it is and exists whenever he says it does.”

The inability to communicate verbally or behaviorally does not negate the possibility the person is experiencing pain. This definition of pain encompasses the subjective component and acknowledges the patient as the best judge of his or her own pain experience. Experts in the field of pain have come to accept that the patient’s self-reporting of pain, including its characteristics and intensity, encompasses the most reliable assessment. This belief that the patient in pain is his or her own best judge is also accepted as the basis for pain assessment and management by such regulatory agencies as the Joint Commission, formerly known as the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations5 as well as such professional organizations as the American Pain Society (APS).6

Practice Point

Practice Point

Pain is what the person says it is and exists whenever he or she says it does. The true etiology of pain isn’t known. More research is needed to learn the true cause of the individual patient’s pain.

Types of Pain

Pain can be nociceptive or neuropathic or have components of both as commonly experienced with wound-associated pain. Nociceptive pain can result from ongoing activation of primary afferent neurons by noxious stimuli, with a normally functioning nervous system. Neuropathic pain is initiated or caused by a primary lesion or dysfunction of the nervous system.7

The two types of nociceptive pain are somatic and visceral. Somatic pain arises from bone, skin, muscle, or connective tissue. It’s usually gnawing, aching, tender, or throbbing and well localized. Pressure ulcer pain is usually somatic in nature. Visceral pain arises from the internal organs such as the gut or from an obstruction of a hollow viscous organ, as occurs with a blockage of the small bowel. Visceral pain is poorly localized and is commonly described as cramping. Both types of nociceptive pain respond well to nonopioid and opioid pain medication.

The origin of neuropathic pain is from an abnormal processing of the sensory input by the peripheral or central nervous system (CNS). The pain is typically described as having burning, stabbing, stinging, shooting, or electrical characteristics. Diabetic neurotrophic foot ulcer pain and the pain of shingles are examples of neuropathic pain. Neuropathic pain responds more readily to adjuvant agents, including antidepressants (e.g., tricyclic, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, SSRI) or anticonvulsant therapy. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCA), such as amitriptyline, nortriptyline, or desipramine, are good choices because of their antinoradrenaline activity. Amitriptyline is a first-generation tricyclic agent with almost equal antinoradrenaline, antihistamine, antiserotonin, and antiadrenergic actions. Nortriptyline is a second-generation tricyclic that has higher antinoradrenaline activity at a lower dose, with fewer side effects such as double vision, dry mouth, and urinary retention. Desipramine has the same advantages as nortriptyline with less drowsiness. Duloxetine is an SSRI that has been approved for the treatment of painful peripheral diabetic neuropathy. The analgesic effect is likely related to augmentation of the inhibitory pain pathways in decreasing the perception of pain. If antidepressive agents are not tolerated or provide inadequate relief of neuropathic pain at reasonable dosages, then anticonvulsants, such as gabapentin and its derivative pregabalin, should be considered. Gabapentin has demonstrated a reduction in neuropathic pain.8 Pregabalin has also proved to be useful in the treatment of neuropathic pain, with studies demonstrating a benefit in painful postherpetic neuropathy9 and painful diabetic neuropathy.10 Both gabapentin and pregabalin require dose adjustments in patients with renal disease.

Pain can also be acute (intermittent) or chronic (persistent). Acute pain has a distinct onset, with an obvious cause and short duration, and is usually associated with acute wounds, subsiding as healing takes place. Chronic pain can be from a chronic wound or other long-term disease, such as cancer. If it persists for 3 months or more, chronic pain is usually associated with functional and psychological impairment. Chronic pain can fluctuate in character and intensity.

The American Geriatric Society (AGS) 11 supports the terminology of “persistent” pain rather than “chronic” pain to circumvent the negative stereotypes that have been associated with the word “chronic.” The AGS Clinical Practice Guideline, “The management of persistent pain in older persons,” states: “Unfortunately, for many elderly persons, chronic pain has become a label associated with negative images and stereotypes commonly associated with long-standing psychiatric problems, futility in treatment, malingering, or drug-seeking behavior. Persistent pain may foster a more positive attitude by patients and professionals for the many effective treatments that are available to help alleviate suffering.”11

Persistent and acute wound-associated pain can occur at the same time; similarly, nociceptive and neuropathic pain may occur simultaneously. Wound-associated pain is often a combination of nociceptive and neuropathic pain. It may be compounded by an inflammatory process that occurs from local tissue damage due to surgery, infection, trauma, or other inflammatory conditions. Inflammation and infection are characterized by redness, heat, and swelling that have been associated with an increased sensitivity to pain in and around the wound site.12–14 Inflammation or infection-associated pain usually resolves when the condition that provoked the pain is controlled. Local tissue ischemia has also been implicated as a contributing factor to increased pain sensation in the acute phase of wounds.12

Regardless of the types and etiologies, pain can be debilitating and associated with sleep disturbance, poor appetite, functional decline, and/or psychosocial maladjustment. Patients suffering from pain reported decreased quality of life that extends beyond its physical component.

Practice Point

Practice Point

Reframing the phrase “the patient complains of pain” to “the patient reports pain” may help to foster a more positive and objective way for practitioners and caregivers to connect with the patient’s experience of pain. Use the term persistent pain rather than chronic pain.

The Persistent (Chronic) Pain Experience

Krasner15–17 has conceptualized pain in chronic wounds as the chronic wound pain experience. Within this model, pain is divided into three categories: noncyclic, cyclic, and chronic pain. Noncyclic or incident pain is defined as a single episode of pain that might occur, for example, after wound debridement. Cyclic or episodic pain recurs as the result of repeated treatments, such as dressing changes, debridement, or turning and repositioning. Chronic or continuous pain is persistent and occurs without manipulation of the patient or the wound. For example, the patient may feel that the wound is throbbing even when he or she is lying still in bed and with no treatment occurring at the local wound site.

Practice PointInterventions for Noncyclic Wound Pain

Practice PointInterventions for Noncyclic Wound Pain

- Identify and develop a pain treatment plan for potentially painful procedures.

- Administer topical or local anesthetics.

- Consider an operating room procedure under general anesthesia rather than bedside debridement for large, deep ulcers.

- Administer opioids and/or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs before and after procedures.

- Assess and reassess for pain before, during, and after procedures.

- Avoid using wet-to-dry dressings that can cause pain and trauma upon removal.

- Consider alternatives to surgical/sharp debridement, such as transparent dressings, hydrogels, hydrocolloids, hypertonic saline solutions, or enzymatic agents.14

Practice PointInterventions for Cyclic Wound Pain

Practice PointInterventions for Cyclic Wound Pain

- Perform interventions at a time of day when the patient is less fatigued.

- Provide analgesia 30 to 60 minutes before dressing change.

- Assess the patient for pain before, during, and after dressing changes.

- Provide analgesia 30 to 60 minutes before whirlpool.

- If the patient’s dressing has dried out, thoroughly soak the dressing—especially the edges—prior to removal.

- Observe the wound for signs of local infection.

- Gently and thoroughly cleanse or irrigate the wound to remove debris and reduce the bacterial bioburden, which can cause contaminated wounds to become critically colonized or infected. Infection will increase the inflammation and pain at the wound site.

- Avoid using cytotoxic topical agents.

- Avoid aggressive packing. (Fluff; do not stuff!)

- Avoid drying out the wound bed and wound edges.

- Protect the periwound skin with sealants, ointments, or moisture barriers.

- Minimize the number of daily dressing changes.

- Select pain-reducing dressings that include moisture balance for healable wounds and avoid aggressive adhesives.

- Avoid using tape on fragile skin.

- Splint or immobilize the wounded area as needed.

- Utilize pressure-reducing devices in bed or when seated in a chair.

- Provide analgesia as needed to allow positioning of patient.

- Avoid trauma (shearing and tear injuries) to fragile skin when transferring, positioning, or holding a patient.

Practice PointInterventions for Persistent (Chronic) Wound Pain

Practice PointInterventions for Persistent (Chronic) Wound Pain

- Use all of the interventions listed for noncyclic and cyclic wound pain.

- Control edema.

- Control infection.

- Monitor wound pain while the patient is at rest (at times when no dressing change is taking place).

- Control pain to facilitate healing and positioning.

- Provide regularly scheduled analgesia, including opioids, patient-controlled analgesia, and topical preparations such as lidocaine gel 2%, depending on the severity of pain.

- Attend to non–wound-associated pain from:

- Comorbid pain syndromes such as contractures and neuropathic pain associated with diabetes/other neuropathies

- Iatrogenic device insertions, such as central lines, venous puncture sites, catheters, feeding tubes, blood gas drawing, or other equipment or procedures

- Comorbid pain syndromes such as contractures and neuropathic pain associated with diabetes/other neuropathies

- Address the emotional component of the pain or the patient’s suffering:

- What does the wound represent to the patient?

- What does pain mean? Is it associated with loss of function?

- Has the wound altered the patient’s body image?

- Did unrelieved pain alter the patient’s mental status or behavior?

- What does the wound represent to the patient?

Pain and Wound Types

The type of pain a patient experiences depends largely on the type of wound present. Pain can occur in patients with acute and chronic wounds and can be related or unrelated to the wound or its cause. Clinicians should determine whether pain is generalized, regionalized, or related directly to the wound bed. Regional pain often relates to the wound cause. Localized wound pain may relate to local wound manipulation, treatment modalities, or infection.18 Gardner and Frantz18 identified increased wound-associated pain as a potential symptom of infection. This section discusses various types of wounds and the types of pain that accompany them.

Pressure Ulcer Pain

Pain at the site of a pressure ulcer is supported by pressure ulcer experts and anecdotal reports by clinicians, although few studies concerning pressure ulcer pain have been published. At its first conference in 1989, the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) stated that “pressure ulcers are serious wounds that cause considerable pain, suffering, disability, and even death.”19 van Rijswijk and Braden20 reevaluated the AHCPR Treatment of Pressure Ulcer guidelines in light of studies published after the guidelines were released in 199421 and reaffirmed the panel’s first recommendation about assessing pressure ulcer patients for pain. Based on additional evidence from studies supporting pain reduction with the use of moisture-retentive dressings, however, van Rijswijk and Braden20 proposed that the 1994 AHCPR recommendations concerning pain and pressure ulcers be rewritten.

The etiology of pain in patients with pressure ulcers is often unknown. Pieper22 quotes the work of Rook23 and suggests that the common sources of pressure ulcer pain are from the “release of noxious chemicals from damaged tissue, erosion of tissue planes with destruction of nerve terminals, regeneration of nociceptive nerve terminals, infection, dressing changes, and debridement.” In stage III or IV pressure ulcers, this pain may come from ischemic necrosis of the tissue triggered by a deep tissue injury or shear forces. Superficial stage II ulcers may be associated with skin surface pain from moisture or friction.

According to a study by Szors and Bourguignon,24 pressure ulcer pain depends not only on the stage of the ulcer but also on whether a dressing change is taking place at the time the assessment is made. The majority of patients in their study (88%) reported pressure ulcer pain with dressing changes; a lower number of patients (84%) had persistent pain at rest. Patients rated the pain from sore to excruciating. Seventy-five percent rated their pain as mild, discomforting, or distressing; 18% rated their pain as horrible or excruciating. Clinicians need to ensure adequate pain control for patients with persistent pain with long-acting pain and breakthrough medication; they must also time the breakthrough medication so that it is effective against the pain experienced at dressing change. In addition, appropriate cleansing and debridement methods and suitable dressings need to be chosen that will minimize wound surface pain and trauma at the time of removal and reapplication.

In 2009, Pieper and colleagues25 published a NPUAP position paper based on a systematic review of the pressure ulcer pain literature of which 15 studies met their inclusion criteria. Four studies were on topical medication treatment and the others on various other pain treatments, assessment, and the pain experience. Their findings included choosing dressings that minimum pain. They were unable to find studies regarding nutrition and pressure ulcer pain but did discuss the potential of nausea and decreased appetite for patients with pressure ulcers experiencing pain. These authors were also able to identify gaps in the research literature for special groups such as neonates, children, bariatric, and end of life patients. In 2010, Langemo and Black published a NPUAP white paper that includes recommendations for assessing, preventing, and treating pressure ulcer pain in the population of 300 million individuals who receive palliative or end of life care.26

Arterial Ulcer Pain

Pain associated with peripheral vascular disease can be due to intermittent claudication or to rest pain with advanced disease that may be more prominent at night with leg elevation. Intermittent claudication pain results from physical exertion or exercise-induced ischemia and has been described as cramping, burning, or aching. The blood flow with exertion is inadequate to meet the needs of tissues. Patients can employ several tactics to relieve pain. The most important are to stop smoking, start gradual and regular exercises, lose weight, and have vascular risk factors treated.

Nocturnal pain may have the same symptoms but usually precedes the occurrence of rest pain. Rest pain occurs—even without activity—when blood flow is inadequate to meet the needs of tissues in the extremities. These types of pain are described as a sensation of burning or numbness aggravated by leg elevation where gravity no longer can facilitate local blood flow. The pain is constant and intense and isn’t easily relieved by pain medications. Pain can sometimes be alleviated by stopping the activity or exercise and placing the legs in a dangling or dependent position (head of bed on blocks) to promote gravity-assisted blood flow. Some patients find relief with gentle massage, while other wear socks to help maintain warmth.

Venous Ulcer Pain

Venous ulcer pain can have several possible sources:

- Edema due to extravasated fluid from the capillaries

- Inflammation of woody fibrosis: acute or subacute lipodermatosclerosis

- Bacterial damage

- Superficial increased bacterial burden (NERDS©)27,28

- Deep and surrounding skin cellulitis (STONES©)27,28

- Superficial increased bacterial burden (NERDS©)27,28

- Inflammation of the veins: superficial and deep phlebitis

The range of venous ulcer pain is extensive; the patient may report mildly annoying pain, a dull ache, or sharp, deep muscle pain. Pain is more intense at the end of the day secondary to edema resulting from the legs being in a dependent position, and this dependent edema is often aggravated by standing, sitting, or crossing the legs. The pathophysiology of venous disease is related to reduction or occlusion of blood return to the heart. Incompetent superficial, perforating, or deep veins can cause pooling of fluid in the legs leading to pitting edema and resultant pain. To minimize pain, patients should be instructed to elevate the legs when sitting and encouraged to wear support stockings. Stocking selection is based on accurate individualized measurement, and their effectiveness relies on putting them on before the legs are placed on the floor in the morning. Other clinical management goals that help to minimize venous disease–related edema include the avoidance of prolonged sitting, weight reduction, and smoking cessation.

Thrombus formation in the deep veins can lead to leg swelling and pain, mimicking an infection or acute lipodermatosclerosis. The patient may report localized tenderness and pain over the long and short saphenous veins. Increased bacterial burden in the superficial wound bed can lead to delayed healing and localized pain. Clinicians should look for three or more NERDS27,28 signs: nonhealing wounds; increased exudate; red, friable granulation tissue; new debris or slough on the surface; and an unpleasant smell or odor. (For more information about NERDS and STONES, see Chapter 7, Wound Bioburden and Infection.) When venous disease has been present for a long period of time, the veins become leaky with fibrin extravasation into the dermis (woody fibrosis). In addition, red blood cells can leak into the tissue, causing staining that’s often referred to as hemosiderin and hyperpigmentation. The woody fibrosis does not go away at the end of the day, and patients can have acute and chronic inflammatory changes within the woody fibrosis, leading to acute and chronic lipodermatosclerosis-type pain.

Neuropathic Ulcer Pain

Neuropathy is the most common complication of diabetes. The amount of pain present depends on the severity of the neuropathy. Unlike stimulus-dependent nociceptive pain, neuropathic pain is spontaneous. The patient may state that the pain interferes with his or her entire life—especially the ability to sleep. The affected extremity may feel like it’s asleep (“a block of wood”) or have the “pins and needles” pain that occurs after a part of the body has “fallen asleep” and starts to wake up. The quality of pain can be burning, stinging, stabbing, or shooting and may include increased skin sensitivity to nonnoxious stimuli (allodynia) and itching. True pain relief is accomplished primarily with pharmacologic intervention. All pain needs to be assessed adequately to ascertain the most effective treatment modality. If a patient reports excessive pain in a neuropathic limb that hasn’t had pain before, an infection or acute Charcot joint changes may be developing.

Patients with diabetes lose protective sensation after 10 to 15 years (sooner with poor blood glucose control). This loss of protective sensation allows these individuals to undergo sharp surgical debridement without nociceptive pain, although they may have referred pain in the leg or foot. If persistent nociceptive pain develops in a neuropathic limb, it usually means there’s disruption of the deeper structures. In a person with a foot ulcer, clinicians should check for underlying osteomyelitis. If a patient has a tender, swollen foot without ulceration and an increase in skin surface temperature, there’s a strong possibility of a Charcot foot. Occasionally, a patient may have both osteomyelitis and a Charcot foot.

Practice Point

Practice Point

Determining whether pain in a person with diabetes is the result of neuropathy or is associated with peripheral vascular disease or infection is extremely important because patients with diabetes have a high incidence of peripheral vascular disease. In addition, pain in a painless foot usually indicates disruption of the deeper structures and a strong possibility of associated osteomyelitis, Charcot foot, or even both conditions coexisting.

Understanding Wound Pain

Most of our understanding of wound pain comes from literature about other diseases.29 Clinicians are increasingly acknowledging that pain is a major issue for patients suffering from many different types of wounds.29 Several consensus statements and other documents regarding wound pain during dressing changes are available to help clinicians manage this type of pain properly.

Practice PointPain: What We Know, What We Don’t Know

Practice PointPain: What We Know, What We Don’t Know

McCaffery and Robinson4 reported on nurses’ self-evaluation of their knowledge about pain.

- Observable changes in vital signs must be relied upon to verify a patient’s report of severe pain: False (answered correctly by 88.4%).

- Pain intensity should be rated by the clinician, not the patient: False (answered correctly by 99.1%).

- A patient may sleep in spite of moderate or severe pain: True (answered correctly by 90.6%).

- Intramuscular (IM) meperidine is the drug of choice for prolonged pain: False (answered correctly by 85.6%).

- Analgesics for chronic pain are more effective when administered as needed rather than around the clock: False (answered correctly by 92.7%).

- If the patient can be distracted from the pain, the patient has less pain than he or she reports: False (answered correctly by 94.7%).

- The patient in pain should be encouraged to endure as much pain as possible before resorting to a pain relief measure: False (answered correctly by 98.4%).

- Respiratory depression (<7 breaths per minute) probably occurs in at least 10% of patients who receive one or more doses of an opioid for relief of pain: False (answered correctly by 60.5%; clinicians tend to exaggerate the risk of respiratory depression with opioid use; according to McCaffery and Robinson, the risk is <1%).

- Vicodin (hydrocodone 5 mg and acetaminophen 500 mg) is approximately equal to the analgesia of one-half of a dose of meperidine 75 mg IM: False (correctly answered by 48.3%).

- If a patient’s pain is relieved by a placebo, the pain isn’t real: False (answered correctly by 86.1%).

- Beyond a certain dose, increasing the dosage of an opioid such as morphine won’t increase pain relief: False (answered correctly by 57.2%).

- Research shows that promethazine reliably potentiates opioid analgesics: False (correctly answered by 35.1%).

- When opioids are used for pain relief under the following circumstances, what percentage of patients is likely to develop opioid addiction?

- Patients who receive opioids for 1 to 3 days: Answer is less than 1% (correctly answered by 82.8%).

- Patients who receive opioids for 3 to 6 months: Answer is less than 1% (correctly answered by 26.7%).

- Patients who receive opioids for 1 to 3 days: Answer is less than 1% (correctly answered by 82.8%).

International Guidelines

The European Wound Management Association (EWMA)30 has developed a position document on wound pain titled “Pain at wound dressing changes.” The document is subdivided into three sections:

- Understanding wound pain and trauma from an international perspective31

- The theory of pain32

- Pain at wound dressing changes: A guide to management33

In the first section of the document, Moffat and colleagues30 surveyed 3,918 healthcare professionals from the United States and 10 countries in Western and Eastern Europe. The survey respondents indicated that pain prevention was the second highest ranking consideration at dressing change, with trauma prevention being first.30 Pain from leg ulcers was ranked as the most severe pain compared with other wound types, and dressing removal caused the greatest pain.23

A copy of this EWMA position document30 can be found on the Internet and is available in Dutch, English, French, German, Italian, and Spanish (Table 12-1).

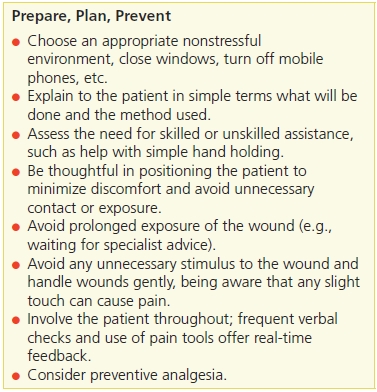

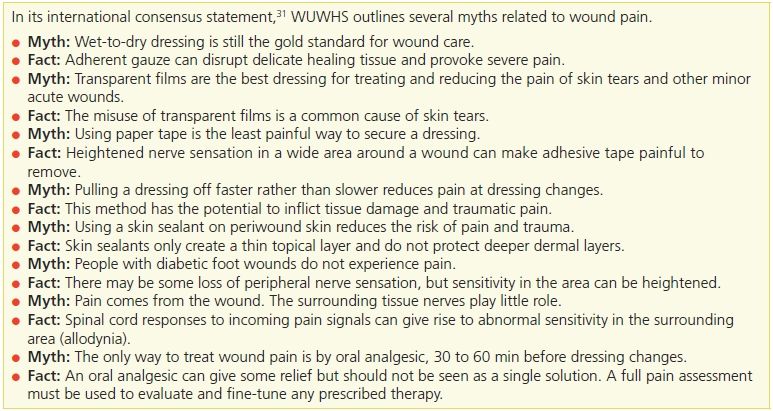

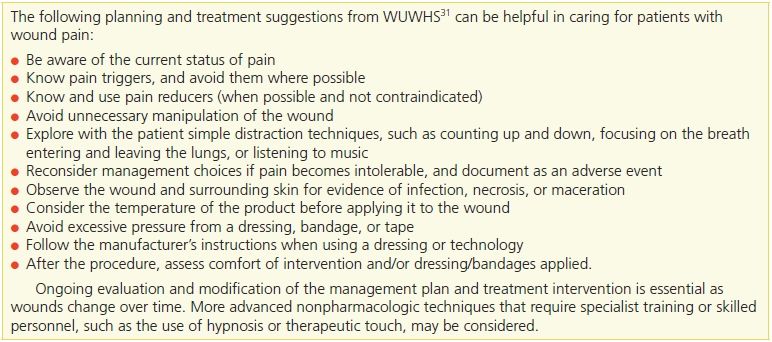

Another international consensus statement was developed by the World Union of Wound Healing Societies (WUWHS).31 This document, entitled “Principles of best practice: Minimizing pain at wound dressing related procedures,” outlines common pain management challenges, myths, and misunderstandings that are useful for improved clinical practice during wound dressing changes (Table 12-2). This document also includes helpful suggestions for care planning and treatment interventions (Table 12-3).

Table 12-2 Dispelling Myths About Wound Pain

Table 12-3 WUWHS Procedural Wound Pain Interventions

Lastly, a third international document (not a consensus statement) addresses the management of pain associated with burns. This document is titled “The management of pain associated with dressing changes in patients with burns” and can be found in the electronic wound care journal, World Wide Wounds.32

Pain Research: Pressure Ulcers

Nursing Management

Nursing management of patients with pressure ulcers sometimes does not adequately address the component of pain management. Hollingworth29 determined that nurses’ assessment, management, and documentation of pain after completing a wound dressing change was inadequate. Likewise, in a qualitative study that examined the reflections of 42 general and advanced practice nurses, Krasner33 identified three distinct patterns nurses used to address pressure ulcer pain in their patients—nursing expertly, denying the pain, and confronting the challenge of pain:

1. Nursing expertly

- Reading the pain

- Attending to the pain

- Acknowledging and empathizing with the patient

2. Denying the pain

- Assuming that it doesn’t exist

- Not hearing the cries

- Avoiding failure

3. Confronting the challenge of pain

- Coping with frustration

- Being with the patient33

Krasner16,17,33 suggested that clinicians use this information to provide more patient-centered sensitive care for patients with pressure ulcer pain.

The Patient’s Pain Experience

Few studies (four quantitative and five qualitative) have been published concerning the pain experience of patients with pressure ulcers. Variability in pain perceptions can be influenced by many contextual and psychological (patient-centered) factors. Woo37 examined 96 patients with chronic wounds to determine whether anxiety or anticipatory pain played a role in the intensity of pain experienced at dressing changes. He uncovered a direct relationship between anxiety related to impending pain that subsequently intensified the experienced pain intensity. With heightened anxiety, environmental and somatic signals are brought to the patient’s attention, sharpening the degree of sensory receptivity and reducing pain tolerance. Woo documented that certain individuals who are insecure in their relationship with others were susceptible to experiencing anxiety and intensified pain.37

The first study to quantify pain by pressure ulcer stage was completed by Dallam and colleagues,14 who documented the perceived intensity and patterns of pressure ulcer pain in hospitalized patients. The study population was diverse, with 66% being white (non-Hispanic) and the remainder being black (non-Hispanic), Hispanic, or Asian. Of the 132 patients enrolled in the study, 44 (33.3%) were respondents and 88 (66.7%) were nonrespondents because they couldn’t communicate responses to the instruments (language and other cognitive barriers). Two different scales were used to measure pain intensity: the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and the Faces Pain Rating Scale (FPRS). (See the next section for additional discussion of these pain scales.) The authors identified a high degree of agreement between the two pain scales. They also noted that the FPRS was easier to use for patients who were cognitively impaired or for whom English was their second language.

The major findings of this important study include the following14:

- The majority of patients with pressure ulcers had ulcer-related pain (68% of respondents reported some type of pain).

- Most patients didn’t receive analgesics for pain relief; only 2% (n = 3) of patients in this population were given analgesics for pressure ulcer pain within 4 hours of the pain measurement.

- Patients who couldn’t express pain or respond to pain scales may still have had pain.

- Patients with deeper pressure ulcer stages (stages III and IV) had more pain.

Some procedures, such as surgical debridement or wet-to-dry dressing changes, may increase pain. While the study didn’t identify the interventions that might be most effective in controlling pain, patients whose beds had static air mattresses rather than regular hospital bed mattresses and those whose wounds were dressed with hydrocolloid dressings had significantly less pain.14 The study also demonstrated that patients are able to differentiate between ulcer site pain, generalized pain, and other local pain sites such as IV and catheter sites.14 Some cognitively impaired patients were able to indicate the presence of pain and respond to pain intensity scales.

Both Dallam et al.14 and Szors and Bourguignon24 discovered that many patients suffer with untreated or undertreated pressure ulcer–associated pain. Dallam and colleagues14 determined that only 2% of patients with pressure ulcer pain received analgesia. Four years later, Szors and Bourguignons24 evaluation documented little improvement in the administration of pain-relieving medication: only 6% of patients with pressure ulcer pain had analgesics prescribed to address their pain.

Both studies reflect the need for clinicians to realize the potential for pain from pressure ulcers. Because only 44 of the 132 patients with pressure ulcer pain could respond to pain scales, Dallam and colleagues14 recommend that pressure ulcer pain should be suspected even when the patient can’t report pain. Both studies recommend further research to identify interventions that can relieve pressure ulcer pain and the associated suffering.

Franks and Collier38 conducted a study in the United Kingdom in which they compared home care patients with (n = 75) and without (n = 100) pressure ulcers. Interestingly, they documented that patients with pressure ulcers had less pain than did those who did not have pressure ulcers. The authors speculated that perhaps pressure ulcer pain might not be the problem, as previously presumed, or that pain control was somehow more effective for patients receiving home care. An alternative explanation is that the home care patients with pressure ulcers did not have the same comorbid conditions as previously reported in hospital populations or that the comparator conditions evaluated in home care may have had greater pain (e.g., infected wounds).

In a quantitative pain study of 128 chronic wound patients, Ayello and colleagues39 found that more than half of the patients with venous ulcers had pain (54%), almost one-third with diabetic neurotropic or neuroischemic ulcers had pain (30%), and one-quarter of those with pressure ulcers (25%) had pain.

Langemo and colleagues40 published a qualitative phenomenological study about pain in pressure ulcer patients. They interviewed eight adults, half with active pressure ulcers at the time of the study and the other half with healed pressure ulcers. Seven themes were identified:

1. the perceived etiology of the pressure ulcer

2. life impact and changes

3. psychospiritual impact

4. extreme painfulness associated with the pressure ulcer

5. the need for knowledge and understanding

6. the need for and stress related to numerous treatments

7. the grieving process.

The fourth theme—extreme pain—was subdivided into three categories: intensity of pain, duration of pain, and analgesic use. Patients commonly referred to the intensity of pain from pressure ulcers with descriptors such as “it burned,” “feeling like being stabbed,” “sitting on a bunch of needles,” or “stinging.” Some examples of statements by actual study respondents include a woman with a stage II pressure ulcer who said, “I felt like somebody was getting a knife and really digging in there good and hard.” In the words of another male respondent, “They (pressure ulcers) are very painful because no matter what way you put your bottom, it hurts.”40

Respondents also commented on the duration of the pain, with statements such as “the majority of the time, even when I was lying down, it hurt.” Pain continued to be a problem even after the pressure ulcer had healed. As one respondent stated, “Every now and again, it still hurts. But there is nothing there. This time there is nothing really there.” The fear of addiction resulting from analgesic use was expressed by some respondents. One respondent with a stage IV pressure ulcer on the buttock commented, “I was constantly in pain and was taking morphine and other types of painkillers to try and ease the pain.”

Another qualitative study reported about the pain of 10 pressure ulcer patients.41 Although Rastinehad identified 22 themes, lack of communication and painful treatment interventions were the two most common complaints.38 Some patients related accounts of communication failures that contributed to stress, tension, and anxiety.41

The European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP) funded a phenomenological study by Hopkins et al. 42 who identified endless pain as one of the three main themes in older people living with pressure ulcers. The eight patients in this study were all over age 65 and had stage III or IV pressure ulcers for more than 1 month. None had spinal cord injuries, as suggested by Langemo and colleagues40 for future qualitative pressure ulcer pain studies. The four subthemes of endless pain were constant pain presence, keeping still, equipment pain, and treatment pain. For some patients, keeping still reduced their pain: “I don’t dare move because everything then gets worse. I lie very still.” For others, pain was exacerbated by pressure-relieving equipment as well as dressing changes. All but one of the patients described their endless pain in a graphic way. “You put a bit of weight on your heel and (it) feels as though it’s burst open.”40

Chronic wound studies43,44 and the studies cited in this chapter emphasize the importance of adequate pain assessment and treatment.

Pain Assessment

Despite the APS’s identification of pain as “the fifth vital sign,”6 it isn’t always included in the assessment of a patient’s pressure ulcer. Dallam and colleagues14 urged that pain be added to the assessment of pressure ulcers and that a patient’s pain status be assessed during dressing changes as well as when the patient is at rest. They also cautioned clinicians to remember that the absence of a response or an expression of pain doesn’t mean that the patient doesn’t have pain. Despite research about the pain experience,14,40,41,43–45 assessment of pain in persons with pressure ulcers continues to be underreported.39 Documentation of pain assessment may vary by chronic wound type, as patients with venous ulcers (63%) and diabetic foot ulcers (53%) in one study were more likely to have their pain assessment recorded compared with those with pressure ulcers (45%).39

Two assessment guides include pain as part of pressure ulcer assessment. The AHCPR21 treatment guidelines include an example of a sample pressure ulcer pain assessment guide in which there is a place to check either yes or no regarding the presence of pain. Ayello’s46,47 ASSESSMENT mnemonic asks the clinician to quantify the patient’s pain experience, including the presence of pain, when the pain occurs (e.g., is it episodic or constant), and if the patient is receiving measures for pain relief. The caregiver checks one of the following boxes under T = tenderness to touch or pain:

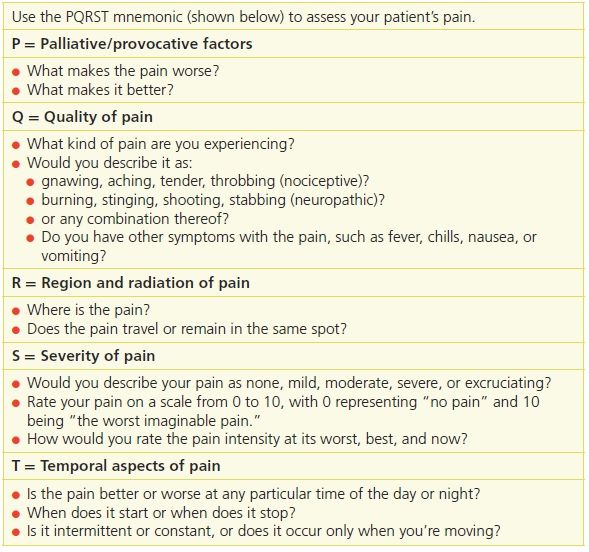

The mnemonic PQRST, which outlines the specific questions to ask the patient, is another useful tool for assessing a patient’s pain14 (Table 12-4).

Table 12-4 Essential Pain Assessment Elements

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree