Origins and Future of Community/Public Health Nursing

Claudia M. Smith

Focus Questions

What are some historical roots of such nursing?

How have subspecialties in community/public health nursing emerged from population-focused care?

What are the distinctions between community-based care and population- or community-focused care?

What issues persist in defining community/public health nursing practice?

Key Terms

Community health nursing

Community/public health nursing

Determinants of health

District nursing

Ecological perspective

Health disparities

Primary health care

Public health

Public health nursing

Visiting nursing

Because community health nursing is a synthesis of nursing and public health, an exploration of the evolution of each of these will strengthen our understanding of the roots of practice. The care of the sick has always been influenced by the meaning given to illnesses, injuries, and human suffering by members of a given culture. Types and prevalences of injuries and illnesses have also influenced care. Other roots of community health nursing include health promotion and disease prevention and population-focused care from public health. Both nursing and public health have been concerned with the interrelationships among people and their physical and social environments.

Public health nursing evolved from visiting nursing and district nursing. Public health nursing included home health nursing. From the 1960s through the end of the twentieth century, the term community health nursing was often used in place of public health nursing. The beginning of the twenty-first century presents yet another transition. The terms community health nursing and public health nursing are linked together in community/public health nursing, and there is a movement to return to the classic name public health nursing (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2007c; Quad Council of Public Health Nursing Organizations, 1999).

Community/public health nursing in the United States has generally evolved from several programs developed in Western Europe, particularly Great Britain. Many people have influenced the development of community/public health nursing. A synopsis of their commitments, ideas, and activities provides an understanding of the foundation of contemporary community health nursing. When possible, the names of specific nurses are included to demonstrate that the history of nursing is the result of the collective efforts of individual nurses. Other community leaders are identified to demonstrate that early community/public health nurses worked in partnerships to create services and obtain financial support. Inclusion of their names allows interested readers to engage in further research.

Roots of community/public health nursing

Visiting nursing originated when concerned laypersons provided care to the sick in their homes. In Europe, the Catholic Sisters of Charity and Protestant deaconesses evolved from groups of such lay nurses. In the United States, organized visiting nursing tended to be provided by nonreligious organizations such as benevolent and ethical societies.

District nursing was started in England in 1859 by William Rathbone, who proposed to Florence Nightingale that visiting nurses who had graduated from nursing school be assigned within a parish or district. In the United States, district nurses often labored in conjunction with physicians who worked in the local dispensary. This was the forerunner of neighborhood or city block nursing.

In the 1880 s, nonprofit visiting nursing associations were formed in several U.S. cities to provide care to the ill and to teach health promotion and disease prevention. Some associations assigned nurses by geographical districts, and others did not.

Lillian Wald included visiting nursing and district nursing within her broader concept of public health nursing. Public health nursing is nursing for social betterment and includes nursing in schools, in clinics, at work sites, and in community centers, as well as in homes. Whether it is called public health nursing or community health nursing, the practice combines caring and activism to promote the health of the public (Backer, 1993).

Visiting Nursing in Europe before 1850

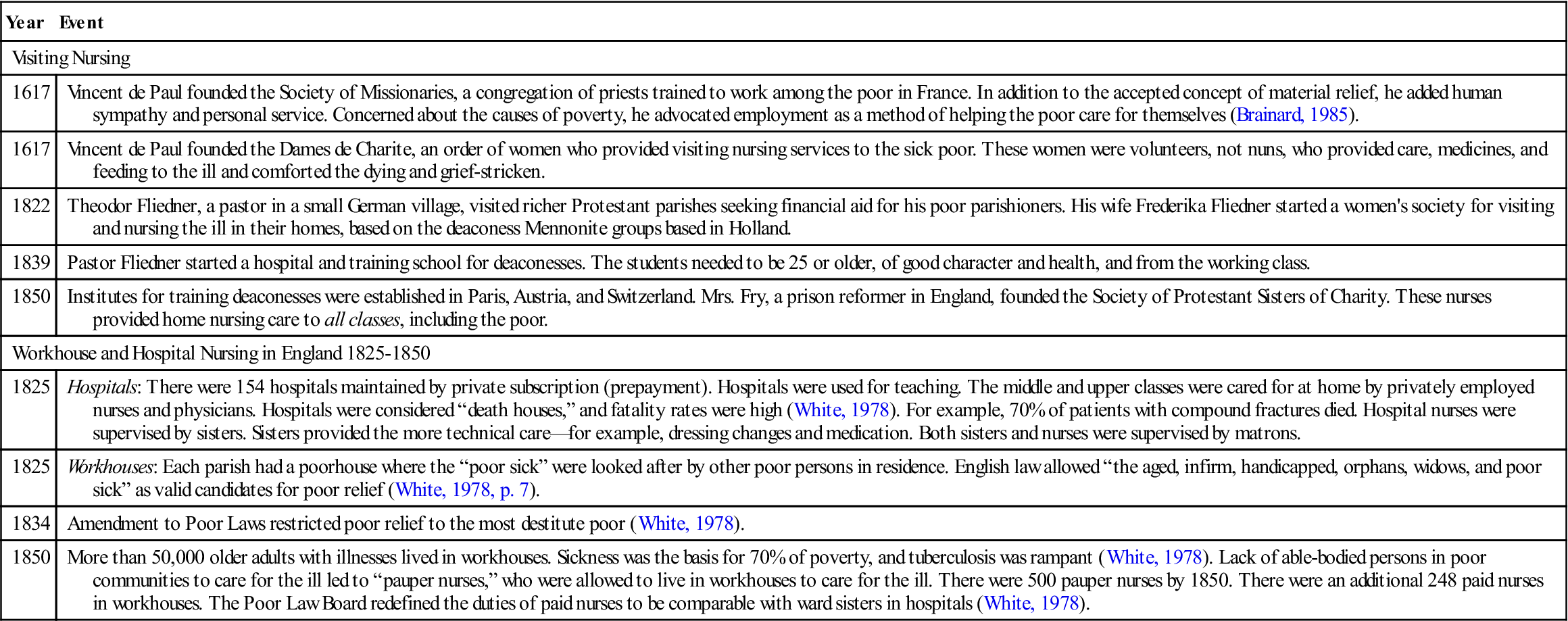

During the Middle Ages, warfare, famine, and plagues persisted in Europe and the Middle East. Hospitals existed for military personnel, and wealthy patients were cared for at home. People became concerned about providing care to the poor and less-well-off members of society. Table 2-1 highlights some of the efforts to address the issue.

Table 2-1

Nursing Efforts in Europe before 1850

| Year | Event |

| Visiting Nursing | |

| 1617 | Vincent de Paul founded the Society of Missionaries, a congregation of priests trained to work among the poor in France. In addition to the accepted concept of material relief, he added human sympathy and personal service. Concerned about the causes of poverty, he advocated employment as a method of helping the poor care for themselves (Brainard, 1985). |

| 1617 | Vincent de Paul founded the Dames de Charite, an order of women who provided visiting nursing services to the sick poor. These women were volunteers, not nuns, who provided care, medicines, and feeding to the ill and comforted the dying and grief-stricken. |

| 1822 | Theodor Fliedner, a pastor in a small German village, visited richer Protestant parishes seeking financial aid for his poor parishioners. His wife Frederika Fliedner started a women’s society for visiting and nursing the ill in their homes, based on the deaconess Mennonite groups based in Holland. |

| 1839 | Pastor Fliedner started a hospital and training school for deaconesses. The students needed to be 25 or older, of good character and health, and from the working class. |

| 1850 | Institutes for training deaconesses were established in Paris, Austria, and Switzerland. Mrs. Fry, a prison reformer in England, founded the Society of Protestant Sisters of Charity. These nurses provided home nursing care to all classes, including the poor. |

| Workhouse and Hospital Nursing in England 1825-1850 | |

| 1825 | Hospitals: There were 154 hospitals maintained by private subscription (prepayment). Hospitals were used for teaching. The middle and upper classes were cared for at home by privately employed nurses and physicians. Hospitals were considered “death houses,” and fatality rates were high (White, 1978). For example, 70% of patients with compound fractures died. Hospital nurses were supervised by sisters. Sisters provided the more technical care—for example, dressing changes and medication. Both sisters and nurses were supervised by matrons. |

| 1825 | Workhouses: Each parish had a poorhouse where the “poor sick” were looked after by other poor persons in residence. English law allowed “the aged, infirm, handicapped, orphans, widows, and poor sick” as valid candidates for poor relief (White, 1978, p. 7). |

| 1834 | Amendment to Poor Laws restricted poor relief to the most destitute poor (White, 1978). |

| 1850 | More than 50,000 older adults with illnesses lived in workhouses. Sickness was the basis for 70% of poverty, and tuberculosis was rampant (White, 1978). Lack of able-bodied persons in poor communities to care for the ill led to “pauper nurses,” who were allowed to live in workhouses to care for the ill. There were 500 pauper nurses by 1850. There were an additional 248 paid nurses in workhouses. The Poor Law Board redefined the duties of paid nurses to be comparable with ward sisters in hospitals (White, 1978). |

Data from Brainard, M. (1985). The evolution of public health nursing (pp. 120-121) New York: Garland; and White, R. (1978). Social change and the development of the nursing profession: A study of the poor law nursing service 1848-1948. London: Henry Kimpton.

The gradual movement toward societal concern for human welfare was hastened during the Industrial Revolution. As workers flocked to cities seeking employment, the cities experienced dramatic overcrowding. Overcrowded slums, lodgings, jails, and workhouses became centers for disease. It was in this environment that reformers sought to prevent deaths through improvement of living conditions.

Scientific knowledge (cause and effect) and the concern for the well-being of individuals provided the intellectual and philosophical bases for responding to the dehumanizing conditions of industrialized, urban Europe. For some, the motivation for reform was the attempt to reconcile Christian principles with the poverty, suffering, and premature deaths of poor persons. Businessmen were beginning to realize that a sick workforce affected production, and therefore, economics provided another motivation.

Birth of District Nursing in England: 1859

Rathbone, a Quaker, merchant, and philanthropist, is considered the originator of district nursing (Brainard, 1985; Gardner, 1936; Monteiro, 1985). Rathbone was a visitor for the District Provident Society in Liverpool, England, and went to the homes of members of his district every week. He believed that personal contacts with the poor could assist people out of poverty and that financial relief alone was insufficient. He persuaded the Liverpool Relief Society to adopt a system whereby the town was divided into districts and subdivided into sections; after a paid relief worker had assessed the situation initially, the “case” was turned over to the friendly visitor in the district for ongoing assistance.

Rathbone sought to expand the district nursing model by employing additional nurses in other areas of Liverpool. Two barriers immediately emerged: public resignation to poverty and suffering and an insufficient number of trained nurses. In 1861, he wrote to Florence Nightingale, who had started a school to train nurses at St. Thomas’s Hospital in London in 1860, to request her assistance in training nurses for Liverpool. She was already engaged in a project for sanitary reform in India, which she directed from England, so she referred him to the Royal Liverpool Infirmary to request that they open a school to train nurses for both the infirmary and district nursing (Monteiro, 1985). With Rathbone’s financial support, such a school was established the next year. A third objective was to provide nurses to care for the sick in private families (Brainard, 1985). By 1865, there were trained nurses in 18 districts of Liverpool (Brainard, 1985; Monteiro, 1985).

The district boundaries were often the same as parishes so that nursing care could be coordinated with the work of the clergy. When a new district was established, partnerships were formed. Meetings were held among the clergy, physicians, residents, and philanthropists for education about the proposal, to enlist cooperation, and to recommend individuals in need of care.

The district nurse visited numerous homes of the “sick poor” for 5 to 6 hours per day. Brainard (1985) summarizes the nurse’s duties (Box 2-1). Generally, district nurses did not provide direct care to persons with communicable diseases, to avoid transmission from one household to another. Instead, nurses taught family members how to perform necessary care and provided the necessary equipment “at the door.”

The nurse was to provide nursing to the sick rather than to give relief in the form of money, food, clothing, or other charity. Nurses were not to make families dependent on them by providing the necessities that the head of the family would ordinarily provide (Brainard, 1985; Monteiro, 1985).

An essential point advocated by Rathbone and Nightingale was that nurses should be trained. Nightingale wrote, “A District Nurse must … have a fuller training than a hospital nurse, because she has no hospital appliances at hand at all” (and because she is the only one to make notes and report to the doctor), as quoted by Monteiro (1985, p. 184). The nurses’ relative autonomy was recognized.

The integration of the public health sanitary movement and nursing can also be seen in Nightingale’s comments that a district nurse must “nurse the room” and report defects in sanitation to the officer of health. Hygiene was seen as an empirical help for recovery from illness and prevention of disease. Thus, environmental health nursing was born.

In 1874, Rathbone persuaded Nightingale to expand district nursing throughout London. The Metropolitan Nursing Association was established in 1875 with Florence Lees, a Nightingale graduate, as president. Its purpose was to provide “nursing to the sick poor at home” (Monteiro, 1985, p. 183). An evaluation of existing district nursing was undertaken. Surveys inquiring about nursing in their districts were sent to clergy and medical officers. Lees personally observed the nurses engaged in district nursing. Finding wide variability in nursing practice, the association sought to standardize the training for district nurses. Nurses were recruited from the class of “gentlewomen,” and after 1 year of hospital training, they received 6 months of supervised district training (Brainard, 1985).

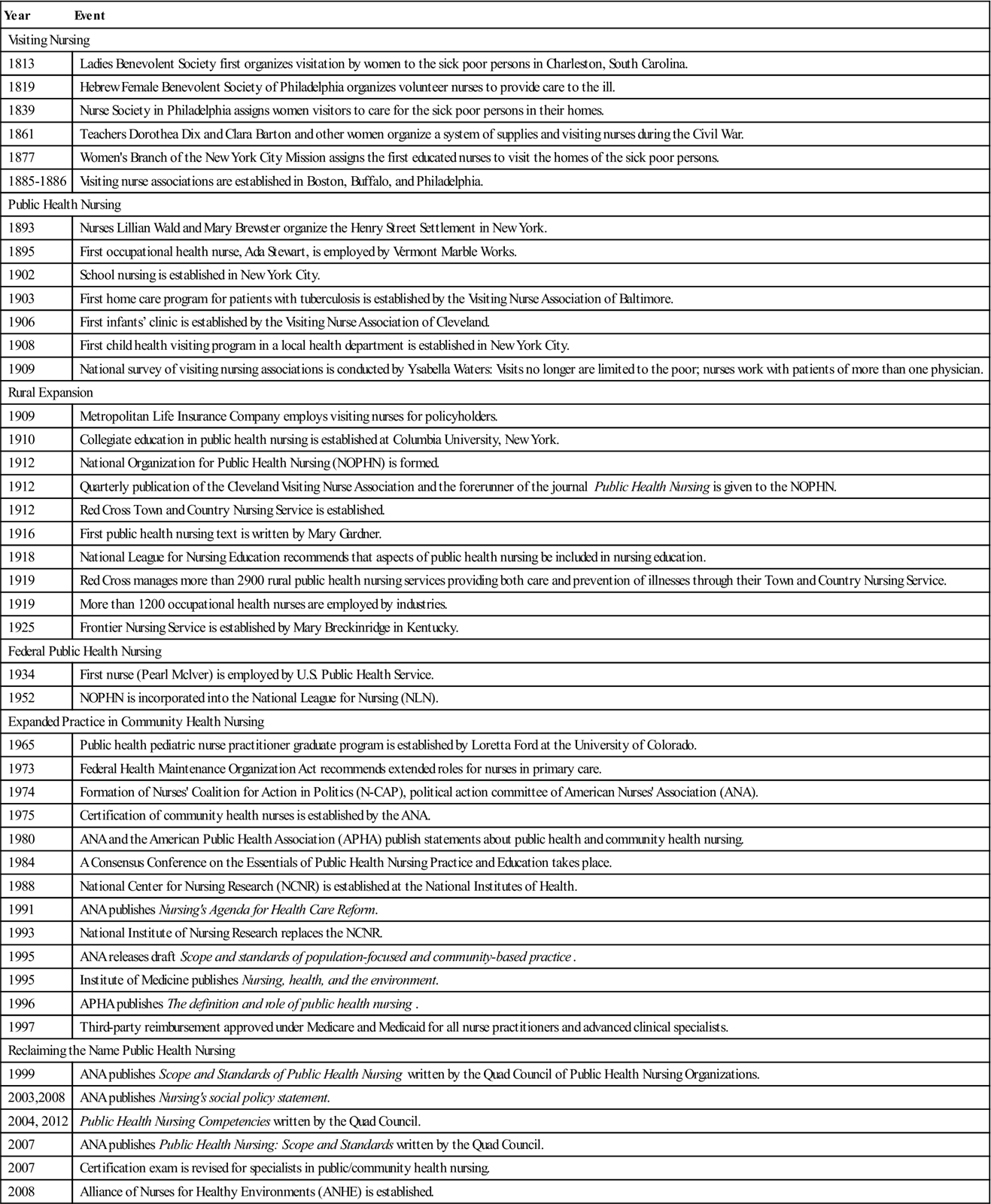

In 1893, at the International Congress of Nursing in Chicago, Florence Craven (née Lees) spoke about district nursing as requiring nurses of intelligence, initiative, and responsibility, with the ability to teach and the commitment to reduce the suffering of poor persons. District nursing had crossed the Atlantic from London. Table 2-2 presents the milestones in U.S. community health nursing, many of which are discussed in greater detail throughout the chapter.

Table 2-2

Dates in U.S. Community/public Health Nursing History

| Year | Event |

| Visiting Nursing | |

| 1813 | Ladies Benevolent Society first organizes visitation by women to the sick poor persons in Charleston, South Carolina. |

| 1819 | Hebrew Female Benevolent Society of Philadelphia organizes volunteer nurses to provide care to the ill. |

| 1839 | Nurse Society in Philadelphia assigns women visitors to care for the sick poor persons in their homes. |

| 1861 | Teachers Dorothea Dix and Clara Barton and other women organize a system of supplies and visiting nurses during the Civil War. |

| 1877 | Women’s Branch of the New York City Mission assigns the first educated nurses to visit the homes of the sick poor persons. |

| 1885-1886 | Visiting nurse associations are established in Boston, Buffalo, and Philadelphia. |

| Public Health Nursing | |

| 1893 | Nurses Lillian Wald and Mary Brewster organize the Henry Street Settlement in New York. |

| 1895 | First occupational health nurse, Ada Stewart, is employed by Vermont Marble Works. |

| 1902 | School nursing is established in New York City. |

| 1903 | First home care program for patients with tuberculosis is established by the Visiting Nurse Association of Baltimore. |

| 1906 | First infants’ clinic is established by the Visiting Nurse Association of Cleveland. |

| 1908 | First child health visiting program in a local health department is established in New York City. |

| 1909 | National survey of visiting nursing associations is conducted by Ysabella Waters: Visits no longer are limited to the poor; nurses work with patients of more than one physician. |

| Rural Expansion | |

| 1909 | Metropolitan Life Insurance Company employs visiting nurses for policyholders. |

| 1910 | Collegiate education in public health nursing is established at Columbia University, New York. |

| 1912 | National Organization for Public Health Nursing (NOPHN) is formed. |

| 1912 | Quarterly publication of the Cleveland Visiting Nurse Association and the forerunner of the journal Public Health Nursing is given to the NOPHN. |

| 1912 | Red Cross Town and Country Nursing Service is established. |

| 1916 | First public health nursing text is written by Mary Gardner. |

| 1918 | National League for Nursing Education recommends that aspects of public health nursing be included in nursing education. |

| 1919 | Red Cross manages more than 2900 rural public health nursing services providing both care and prevention of illnesses through their Town and Country Nursing Service. |

| 1919 | More than 1200 occupational health nurses are employed by industries. |

| 1925 | Frontier Nursing Service is established by Mary Breckinridge in Kentucky. |

| Federal Public Health Nursing | |

| 1934 | First nurse (Pearl Mclver) is employed by U.S. Public Health Service. |

| 1952 | NOPHN is incorporated into the National League for Nursing (NLN). |

| Expanded Practice in Community Health Nursing | |

| 1965 | Public health pediatric nurse practitioner graduate program is established by Loretta Ford at the University of Colorado. |

| 1973 | Federal Health Maintenance Organization Act recommends extended roles for nurses in primary care. |

| 1974 | Formation of Nurses’ Coalition for Action in Politics (N-CAP), political action committee of American Nurses’ Association (ANA). |

| 1975 | Certification of community health nurses is established by the ANA. |

| 1980 | ANA and the American Public Health Association (APHA) publish statements about public health and community health nursing. |

| 1984 | A Consensus Conference on the Essentials of Public Health Nursing Practice and Education takes place. |

| 1988 | National Center for Nursing Research (NCNR) is established at the National Institutes of Health. |

| 1991 | ANA publishes Nursing’s Agenda for Health Care Reform. |

| 1993 | National Institute of Nursing Research replaces the NCNR. |

| 1995 | ANA releases draft Scope and standards of population-focused and community-based practice. |

| 1995 | Institute of Medicine publishes Nursing, health, and the environment. |

| 1996 | APHA publishes The definition and role of public health nursing. |

| 1997 | Third-party reimbursement approved under Medicare and Medicaid for all nurse practitioners and advanced clinical specialists. |

| Reclaiming the Name Public Health Nursing | |

| 1999 | ANA publishes Scope and Standards of Public Health Nursing written by the Quad Council of Public Health Nursing Organizations. |

| 2003,2008 | ANA publishes Nursing’s social policy statement. |

| 2004, 2012 | Public Health Nursing Competencies written by the Quad Council. |

| 2007 | ANA publishes Public Health Nursing: Scope and Standards written by the Quad Council. |

| 2007 | Certification exam is revised for specialists in public/community health nursing. |

| 2008 | Alliance of Nurses for Healthy Environments (ANHE) is established. |

District Visitors and Visiting Nurses in the United States

The first organized lay visitors to “sick poor” persons in America were members of the Ladies’ Benevolent Society of Charleston, South Carolina, founded in 1813 (Brainard, 1985). The society’s formation was a response to the poverty and suffering brought about by a yellow fever epidemic and the trade embargoes during the War of 1812. The society adopted principles that did not appear in England until 40 years later. Membership transcended church and color lines, and patients’ religious beliefs were not interfered with. Although substantial amounts of food, clothing, fuel, bedding, and soap were distributed, money was not given out. The circumstances of “sick poor” persons were investigated, and attempts were made to furnish work for unemployed persons. Charleston was divided into districts that corresponded to election wards. Ladies visited for 3 months. The society existed until the Civil War. In 1881, it resumed its work, and a trained nurse was employed in 1903.

In 1839, the Nurse Society in Philadelphia assigned lady visitors by districts. Responsible women were assigned to act as nurses under the direction of physicians and lady visitors (Brainard, 1985). Although these nurses are considered “the first to systematically care for the poor in their homes” in the United States, they were not trained. Neither did they visit multiple homes; rather, they stayed with one patient until discharged by the physician.

Trained Visiting Nurses in the United States

Visiting nursing by trained nurses in the United States began in the industrialized cities of the Northeast almost 20 years after its inception in Liverpool (Waters, 1912). In 1877, the Women’s Branch of the New York City Mission sent trained nurses into the homes of poor persons; 2 years later, the Society for Ethical Culture placed one nurse in a city dispensary for the purpose of home visiting. Both assigned nurses by districts (Brainard, 1985).

It is not known whether the New York City Mission spontaneously generated the idea of visiting nurses or whether members of their board had visited London (Brainard, 1985). Frances Root, a graduate of the first class of nurses educated at Bellevue Hospital, was the first trained visiting nurse in the United States in 1877. During the next year, the number of nurses expanded to five, and the salary of each was provided by a charitable lady. The philosophy of the New York City Mission focused on fulfilling a religious call, providing material relief, and caring for the ill. There was little focus on instruction in hygiene, sanitation, or prevention.

Felix Adler, founder of the Society for Ethical Culture, was influenced by the New York City Mission, but he wanted nurses to provide care in a nonsectarian way. The nurses employed by the Society for Ethical Culture received their patient assignments from physicians in dispensaries; each nurse visited in the district served by a dispensary. Teaching of cleanliness and proper feeding of infants and children were included as aspects of preventive care.

Settlements were part of a movement among university-educated young adults to reside in communities, to study the communities’ problems through relationships with residents, and to reform the squalid conditions of urban workers (Kraus, 1980). Crowded tenements had insufficient ventilation and no toilets or baths. Fire escapes were also crowded with sleeping people. A police census in 1900 identified more than 2900 persons living in an area smaller than two football fields—approximately 1724 persons per acre (Kraus, 1980, p. 180). In this environment, Wald was committed to providing nursing services to “sick poor” persons. By 1900, there were 15 nurses; by 1909, there were 47 nurses on call; and by 1914, there were 82 affiliated nurses (Kraus, 1980). In 1913, the Henry Street Settlement reached 22,168 persons, or 1048 more than all persons admitted that year to Mount Sinai Hospital, New York Hospital, and Presbyterian Hospital combined (Kraus, 1980, p. 176).

Alleviation of human suffering and illness was profound. The beneficial results in terms of creative nursing practice and the inception of new modes of health care delivery are still with us today.

Associations for Visiting Nursing and District Nursing

In 1886, inspired by district nursing in England, ladies in Boston and Philadelphia founded associations for the sole purpose of trained nurses providing care to “sick poor” persons in their homes (Brainard, 1985; Gardner, 1936). The Women’s Education Association, encouraged by members Abbie Howes and Phoebe Adams, supported the Instructive District Nursing Association of Boston, so named to emphasize the importance of education in nursing work (Brainard, 1985).

The association adopted principles for working with the poor. For example, nurses were not to give money to patients or interfere with patients’ religious beliefs and political opinions (Brainard, 1985). To prevent cross-infection, caring for patients with contagious diseases was limited. Instruction on hygiene, self-care, and prevention was as important as care of the ill. Nurses reported to a single physician, who directed patient care. As the association expanded, professional nursing supervisors were employed, and nurses were expected to help community residents with fund-raising activities to support the association’s work. By 1920, more than 36,000 patients were seen by association nurses each year; of these, 23% were maternity cases.

In Philadelphia, the District Nurse Society, later named the Visiting Nurse Society of Philadelphia, was established with the sponsorship of Mrs. Williams Jinks and other ladies. Like the Boston association, the Philadelphia society had a twofold mission: to care for the sick and to “teach cleanliness and proper care of the sick” (Brainard, 1985, p. 219).

The society employed nurses and attendants and added supervisory nurses in the first year. Fees of $0.50 to $1 were charged for each nurse visit, although services were provided free to those unable to pay. Initially only for poor persons, visiting nurse services expanded around 1918 to include others in need of nursing care. Nurses provided home visits or were available for care of longer duration at an hourly fee ($1.24 to $1.75 per hour) (Brainard, 1985, p. 224).

In the United States, such care was generally known by the term visiting nursing rather than by the English term district nursing (Brainard, 1985). The term visiting nursing was probably adopted because not all nurses were assigned to districts. Many types of organizations employed visiting nurses, including nursing associations, churches, hospitals, industries, and charity organizations. During the 1890 s, the number of visiting nursing associations dramatically increased, especially in northeastern and midwestern cities.

In 1909, Ysabella Waters, a nurse with the Henry Street Settlement, undertook a national survey of organizations that employed trained nurses as visiting nurses. Waters reported a dramatic increase in visiting nursing associations since 1890. She noted that nurses served both the poor and those of greater economic means. A visiting nurse no longer worked primarily with one physician but could accept requests for services from all physicians. Website Resource 2A![]() depicts rules for nurses that were included in Waters’s book; these rules incorporate the principles that first appeared in district nursing.

depicts rules for nurses that were included in Waters’s book; these rules incorporate the principles that first appeared in district nursing.

Public Health Nursing: Nursing for Social Betterment

The demand for even more visiting nursing services led nursing leaders to consider the issue of standards for practice. There was concern that untrained nurses would be hired to meet the expanding demand and that nursing might revert to pre-Nightingale practices. In 1911, Ella Crandall, professor in the Department of Public Health and Nursing at Teachers College in New York, initiated correspondence with other nursing leaders to solicit their opinions about an “organization to protect the standards of visiting nursing” (Brainard, 1985, p. 326).

A joint committee appointed by the American Nurses Association (ANA) and the Society of Superintendents of Training Schools and chaired by Lillian Wald met to consider the issue. They sent letters to more than 1000 organizations in the United States that employed visiting nurses, inviting each to send a representative to a special meeting at the next ANA meeting in June 1912. Eighty replies were received, and 69 organizations agreed to send a delegate (Brainard, 1985; Fitzpatrick, 1975).

The report of the joint committee was accepted. A National Visiting Nurse Association was formed as a member of the ANA, and recommended standards for organizations that employed visiting nurses were accepted (Brainard, 1985; Fitzpatrick, 1975).

The name of the association was debated at length because there had not been any agreement within the joint committee. A majority had favored National Visiting Nurse Association, but Crandall led a vocal minority advocating incorporation of Wald’s term public health nursing (Brainard, 1985; Fitzpatrick, 1975). The reasons for selecting visiting nursing included the fact that it was the term commonly recognized by the public. Public health nursing was a broader term, which encompassed all nurses “doing work for social betterment” and was not limited to those who primarily did home visiting to provide bedside care (Brainard, 1985, p. 332). Public health nursing was general enough to include nurses in schools, tuberculosis programs, hospital dispensaries, factories, settlements, and child welfare organizations, in addition to those providing bedside care through home visiting. Crandall argued that the public health movement would expand and that adoption of the term public health nursing provided a generic label under which new forms of practice could evolve. The organization was finally named National Organization for Public Health Nursing (NOPHN). The word for was consciously selected to allow the participation of nonnurses in promoting the work of public health nursing (Brainard, 1985; Fitzpatrick, 1975). In 1952, the NOPHN merged with the National League for Nursing (NLN), which continues today.

Definition of public health

C.-E. A. Winslow (1877-1957), the leading theoretician of the American public health movement, provided a definition of public health in 1920 (Box 2-2). He asserted that public health is a social activity that builds “a comprehensive program of community service” on the basic sciences of chemistry, bacteriology, engineering and statistics, physiology, pathology, epidemiology, and sociology (Winslow, 1984, p. 1).

Although his original definition of public health focused on the goal of physical health, by 1923, Winslow acknowledged that prevention and treatment of mental illness was an expanding sector of the public health movement (Winslow, 1984). In 1945, Winslow predicted that “public health which was an engineering science and has now become a medical science must expand until it is in addition a social science” (Winslow, 1984, p. x). In 1953, the American Public Health Association (APHA) encouraged “collaboration between public health workers and social scientists to better promote the utilization of social science findings toward the solution of public health problems” (Suchman, 1963, p. 22). In 1963, Edward A. Suchman, professor of sociology at the University of Pittsburgh, described the application of sociology in the field of public health. He noted that both sociology and public health originated in the social reform movement, that both deal with populations of individuals, and that both employ statistical methods. The connection between social context and public health remains. It is especially important in the area of preventive health.

Winslow (1984) specifically named nursing services as an essential part of the organized community efforts that will prevent disease, prolong life, and promote health. He was an advocate for public health nursing, and in 1923, he agreed with William H. Welch (the founder of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health) that public health nursing was one of two unique contributions that the United States had made to public health. Winslow (1984, p. 56) acknowledged public health nurses as “teachers of health par excellence” and recognized teaching as a responsibility additional to “care of the sick in their homes.”

If the environment is healthful, if medical and nursing services are provided to assist the ill, and if individuals are taught about health-related behavior and responsibilities, does a comprehensive community effort for health exist? No, according to Winslow. There must also be “social machinery … [to] ensure a standard of living adequate for the maintenance of health” (Winslow, 1984, p. 1). The science and art of public health are inherently concerned with standard of living.

Public health nursing, as a composite of nursing and public health, is committed to the existence of standards of living sufficient to maintain health. The fields of public health and public health nursing originated in social reform that occurred as a result of the collective commitment of individuals to the health and well-being of others.

Acknowledging this commitment can provide renewed energy and clarity of purpose. Community health nurses who are empowered by this commitment can continue to have an impact on the social and political power structures.

Nursing and sanitary reform

Before 1890, the primary public health measures to control communicable diseases in Europe and the United States were isolation of the ill (quarantine) and enactment of laws governing food markets, water supplies, and sanitation (Duffy, 1990). As a result of the Industrial Revolution, many people moved to cities, where crowded conditions and poor sanitation helped to spread communicable diseases.

Urban Health

Descriptive epidemiological studies laid the groundwork for sanitary reforms in England and the United States (Duffy, 1990). In 1842, Edwin Chadwick published a report on the unsanitary conditions among poor persons in the cities in Great Britain. Lemuel Shattuck founded the American Statistical Society in 1839 and identified high death rates among workers in Boston. His Report of the Sanitary Commission of Massachusetts in 1850 called for government to improve sanitary and social conditions to reduce incidences of disease and death. In 1854, the English physician John Snow demonstrated that the cases of cholera in an outbreak were linked to water from the same well. The germ theory of disease was only emerging. Table 2-3 lists other public health accomplishments in the United States.

Table 2-3

Dates in U.S. Public Health History

| Year | Event |

| U.S. Beginnings | |

| 1793 | First local health department in Baltimore, Maryland |

| 1798 | New York City street cleaning system established |

| 1813 | Federal law to encourage smallpox vaccination |

| 1842 | Massachusetts Registration Act to provide for collecting vital statistics |

| 1850 | Report of the Sanitary Commission of Massachusetts by statistician Lemuel Shattuck |

| 1855 | First state quarantine board in Louisiana |

| 1869 | First state board of health in Massachusetts |

| 1872 | American Public Health Association (APHA) established |

| 1878 | Federal Marine Service Hospital established for seamen with illnesses and disabilities |

| 1881 | American Red Cross founded by Clara Barton |

| 1890 | Federal Marine Hospitals authorized to inspect immigrants |

| Expansion of Local Health Departments | |

| 1894 | First medical inspection of schoolchildren in New York City |

| 1900 | Health departments established in 38 states |

| 1910 | Tuberculosis programs included in local and state health departments |

| 1912 | U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) established |

| 1912 | National Safety Council formed |

| 1935 | Federal Social Security Act to institute Social Security retirement, disability, and survivors’ benefits |

| 1945 | Federal Hill-Burton Act to fund building of community hospitals |

| Expansion of Access to Care | |

| 1963 | Federal Community Mental Health Centers Act |

| 1965 | Amendments to Social Security Act to provide financial mechanisms to pay for health care for poor (Medicaid) and older adults (Medicare) |

| 1965 | Regional Medical Program established to disseminate research findings to the public regarding prevention and treatment of heart disease, cancer, and stroke |

| Health Planning and Cost Controls | |

| 1966 | Comprehensive Health Planning Amendments to the Public Health Service Act |

| 1974 | National Health Resources Planning and Development Act to provide for a system of community-based health planning for the entire nation |

| 1980 | First national health objectives published |

| 1980 | Smallpox eradicated throughout the world through the leadership of the World Health Organization |

| 1983 | Health Resources Planning and Development Act not renewed; national health planning abolished |

| 1983 | Prospective payment system instituted under Medicare |

| Strengthening Public Health and Prevention | |

| 1988 | The Future of Public Health published by the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences |

| 1990 | National Health Objectives for the Year 2000 published |

| 1993 | National legislation introduced for health care reform |

| 1995 | Public health responsibilities and essential public health services described by the Public Health Functions Steering Committee (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]) |

| 2000 | Healthy People 2010 published |

| 2003 | Funds for public health infrastructure provided by the CDC to strengthen preparedness for bioterrorism and other emergencies |

| 2004 | Institute of Medicine recommends health insurance for all in the United States by 2010 |

| 2008 | First exam for Certification in Public Health (CPH) for graduates from Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH)-accredited schools and programs |

| 2010 | Healthy People 2020 published |

| 2010 | Federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PL 111-148) of 2010 mandating health insurance reforms |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree