Older Adults in the Community

Sally C. Roach*

Focus Questions

What crises do aging families experience?

What are the common health care needs of older adults?

What support systems are available to meet the needs of an aging society?

Key Terms

Aging

Case management

Congregate housing

Durable power of attorney

Foster care

Geriatric Evaluation Service (GES)

Gerontology

Group homes

Home care

Life-care (continuous-care) community

Living wills

Long-term care

Medical daycare

Multipurpose senior centers

Retirement communities

Respite care

Social daycare

With the growing population of people 65 years of age and older, complex and unique health care needs have emerged that call for knowledge and expertise in the field of gerontology. Gerontology has been defined as the study of aging persons and of the process of aging (Miller, 2011). The term gerontology is derived from the root word gera or geron, meaning “great age” or “privilege of age.”

At the onset of the 20th century, older adults made up only 4% of the U.S. population (3.1 million individuals). By mid-century, this number had grown to 12.3 million older adults or approximately 8% of the population (Rice & Fineman, 2004). In 2008, this group continued to grow to 39 million, representing 13% of the U.S. population. The “baby boomers” (children born between 1946 and 1964) began turning 65 in 2011, and the number of older adults will increase dramatically between 2010 and 2030. Between 2001 and 2030 the number of older adults will increase from 35 million to 72 million, representing nearly 20% of the population (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2010)

Regardless of which clinical setting nurses choose to work in, the majority of nurses will care for older adults in their careers. In fact, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) (2007) states that nurses are the largest members of hospital staffs and are the primary providers of older adult care in both hospitals and nursing homes. Consequently, nurses must be knowledgeable about the unique health care needs of an increasingly aging population. It is particularly important for community health nurses to understand the needs of older adults, because only about 5% of the Medicare population resides in long-term care facilities, leaving the remaining 95% of older adults living in the community. Approximately 2% of older adults living in the community require assistance to remain living independently (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2010).

This chapter explores the role of older adults in the family and community in light of developmental and sociocultural influences, unique crises experienced by aging families, and the need for support systems to assist families coping with the crises of aging. Common health care needs of older adults in the areas of nutrition, medication, mobility, and social isolation are reviewed. The influence of poverty is examined in view of its impact on the health of older Americans and their ability to secure needed health care services.

Legislative trends in health care and social services for older adults arising in response to the changing demography of the U.S. population are identified. These political actions have had great influence on the development and organization of community resources for older adults. The federal, state, and local governments and social concern for the welfare of older adults have resulted in the development and organization of nationwide services for older adults. Finally, the responsibilities of the community health nurse as facilitator-collaborator, advocate, teacher, and case manager in working with the older adult client in the community are explored.

Aging

Meaning

Aging can be viewed in both objective and subjective terms. What does it mean to be old in contemporary Western society? Is one “old” when he or she reaches the age of 65 years? In 1935 the federal government adopted 65 years as the official threshold of “elderliness.”

Aging is a universal human experience that culminates in an end. It is a dynamic state of existence that changes with one’s perspective. Meanings of old age are based on societal views of aging, cultural beliefs about the meaning of being old, and values associated with old age.

Myths

Common myths about older adults are that they are frail, senile, unhealthy, unhappy, set in their ways, irritable, lacking in interest in matters of sexuality, and ineffective and undependable as workers (Cruikshank, 2009). In fact, 80% of older persons are healthy enough to engage in normal activities. Although reaction time slows with age, older persons are not senile and do not have serious memory deficits. Older people are not set in their ways. Most have had to adapt to such major life events as retirement, having children leave home, and declining health.

Studies also show that older working Americans work as effectively as their younger counterparts. They change jobs less frequently, have fewer job-related accidents, and have lower rates of absenteeism. Most older adults also report that they feel relatively satisfied most of the time. Most do not feel any significant restriction on their daily life (Rice & Fineman, 2004). Overall, older adults experience frequent social contacts with friends or relatives, participate in church-related activities or voluntary organizations, and continue to have interest in and a capacity for sexual relations (Miller, 2011). Some facts about older adults are listed below (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2010; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2003):

Chronology

Chronology is a poor measure of aging, as persons 65 years and older may span an age range of 40 or more years and may experience diverse and unique needs during this time. For this reason, some theorists make a distinction between the young-old and the old-old. The old-old have been defined as persons 85 years and older, and the young-old are persons between the ages of 65 and 74 years (Leppik, 2006). Other theorists argue that aging should be defined not in terms of chronology but in terms of biopsychosocial functioning (Ebersole et al., 2008). However aging is defined, a growing aging population is a demographic reality with definite health care implications. An increase in the prevalence of chronic diseases and functional impairments (i.e., the ability to perform activities of daily living) can be expected. The need for health care services for chronically ill persons will increase. An increase in chronic illness and residual disability will necessitate more long-term care. Medical care expenditures will increase in proportion to the greater number of older adults in need of health care services (Congressional Budget Office [CBO], 2007). These trends will require that health care providers have a thorough understanding of the unique health care needs of a growing aging population.

Role of older adults in the family and the community

Less than half of all children born at the turn of the 20th century could expect to live to age 65. Today, approximately 80% can expect to live to age 65. The U.S. Census Bureau projects that the population age 85 and over could grow from 5.3 million in 2006 to 21 million by 2050 (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2010).

Developmental Tasks and Crises of Aging Families

As people age, they face new challenges, new life experiences, and new life crises. Erikson and colleagues (1994) conceived the primary developmental task of old age as the achievement of integrity over despair. Integrity refers to a sense of wholeness and meaning in one’s past and present experiences. Despair involves a sense of dread and hopelessness and the feeling that life lacks meaning and purpose. The developmental task of old age includes the reaffirmation of meaning in life and the acceptance of the inevitability of death (Erikson et al., 1994).

Maintaining a sense of wholeness and purpose may represent a challenge in the midst of declining health and significant alterations in major life roles and relationships. Such major developmental life events as retirement, loss of significant others, and the dependency incurred by declining health produce multiple role changes and may precipitate a major life crisis, or may be viewed as an opportunity for growth (Newman & Newman, 2009).

Retirement as a Developmental Task

Role changes that accompany the aging process are often abrupt and undesired (Ebersole et al., 2008). A person’s occupation represents a significant societal role that may be interrupted by illness or retirement, both of which may be viewed as undesirable. Retirement is a withdrawal from a given service in society; operationally, retirement is measured by counting those who are no longer employed full-time. Most people older than 65 years are retired; however, some continue to work out of necessity or desire. There were 36% of men age 65 to 69 and 26% of women age 65 to 69 in the civilian labor force in 2008 (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2010).

Advantages of retirement include freedom from work, more leisure time, and the eligibility to collect retirement benefits or pensions. Despite these advantages, some may feel useless, unproductive, or worthless after losing this significant role. Men, in particular, who retire unwillingly, are at a significant risk for alcoholism, depression, and suicide. For this reason, it is important that persons receive adequate support and counseling in preparation for retirement. The community health nurse working in home settings and skilled in working with families is uniquely prepared to provide this service. The occupational health nurse can engage in preretirement planning with clients in the middle years, long before retirement becomes a reality.

Although federal legislation prohibits mandatory retirement based on age, most workers in private or government sectors may still be encouraged to leave work through early retirement incentive programs (Ebersole et al., 2008). The community health nurse may be responsible for coordinating preretirement planning programs. These programs should include information on attitudes toward retirement, retirement benefits, legal aspects of retirement, the effects of retirement on family relationships, and possible uses of leisure time. The American Association of Retired Persons (AARP), a national organization devoted to the needs of older Americans, publishes a package of training materials for coordinators of preretirement programs.

Loss and the Older Adult Population

Women are more likely to experience the loss of a spouse. With increasing age, the proportions of women who are widowed rose rapidly: 24% of women ages 65 to 74 and 56.9% of women 85 and older are widowed compared with 6.4% and 21.2% of men, respectively (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2011). The death of a spouse or loss of another significant person through death or relocation (e.g., children leaving home) represents a major life crisis that requires support and intervention. The loss of a loved one is an important predictor of physical and emotional decline in the older adult client. Clients who experience the loss of a spouse or significant other may grieve not only for the lost person but also for the loss of multiple roles provided by that person (e.g., loss of a lover, a homemaker, a comforter, a provider). Widows are less likely to remarry than widowers because older adult women significantly outnumber older adult men. In addition, the loss of a spouse may necessitate relocation, which further contributes to the sense of loss and the disruption of integrity in one’s life.

As people age, they are likely to experience the deaths of significant others of their own age and cohort. The loss of a significant other represents the loss of a part of one’s past and of life history. The experiences shared with the lost person and the ability to fondly recall memories together are partially lost when the co-creator of these memories is no longer present. Anger, guilt, loneliness, and depression are common outcomes.

The community health nurse can provide support by encouraging reminiscence (i.e., by acknowledging meaningful past experiences and times of distress and by assisting the client to identify past coping mechanisms), assessing for signs of depression and suicidal intention, and assisting clients to grieve. Clients may be referred to support groups in the community that provide an opportunity to share experiences, to draw on others for support, and to establish new relationships.

Declining Health

The multiple losses experienced with aging are represented not only through the loss of significant others but also through the experience of declining health. Seventy-three percent of older adults rate their health as good or better (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2010). The chance of experiencing health impairment increases with age, and those with more than one chronic condition report greater limitations. In 2009, 38% of persons 75 or older had a heart condition, 20% experienced a cancer illness and 12.5% had had a stroke (USDHHS, 2011).

Dependency

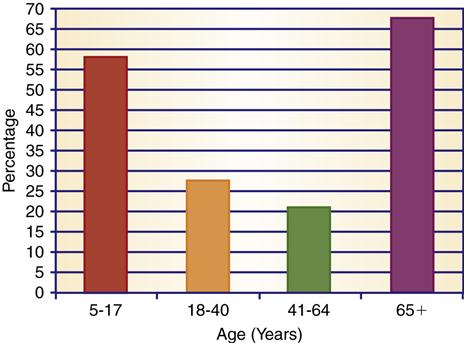

The likelihood of increased disability with age also increases the likelihood of dependency on others (Figure 28-1). This increased dependency may produce feelings of guilt, anger, frustration, and depression in clients and their families.

Percentage of adults who report some disability: 2005. (From U.S. Bureau of the Census. [2008]. Americans with disabilities: 2005. Current Population Reports P70-117. Washington, DC: Author.)

Research indicates that approximately 83% of older adults who need long-term care reside at home and receive care from informal caregiving systems (e.g., family, friends, or neighbors). (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010a). The majority of the U.S. adult population either is or expects to be a caregiver. In the next five years, 49% of U.S. workers expect to have to care for an older family member (AARP, 2011a). Most of the burden for family caregiving falls to middle-age and young-old adults. The term “sandwich generation” refers to middle-age persons who are juggling the support for adolescent and college-bound children and the care of parents. In fact, with the increase in life expectancy, middle-age persons may find that four generations are ultimately dependent on them (i.e., children, grandchildren, parents, and grandparents), and older adults (65 years and older) may be expected to care for old-old parents.

Many women and men balance multiple and competing demands to care for an older adult family member (CDC, 2010a). The pool of family caregivers is dwindling and is not likely to meet the need in the future. In 1990 there were 11 potential caregivers for each person needing care (Mid-East Area Agency on Aging, 2003). Now, the population of persons 65 and older is increasing by 2.3% per year while the number of family members available to provide care is increasing at the rate of only 0.8% (CDC, 2010b).

Caregivers report increased stress and are often placed in economic jeopardy because of care needs. American businesses lose approximately 34 billion dollars yearly because of employees’ needs to care for loved ones, and the value of unpaid caregiving for older adult family members is 450 billion dollars a year (AARP, 2011a). The level of caregiving required often demands significant readjustment in employment or job resignation, which may lead to financial burden and a significant alteration in family relationships. This problem is compounded by the scarcity of services available to support family caregivers.

Older age brings adjustments for the entire family, with changing roles and relationships. Intergenerational dependency and support of the aging family are greatly influenced by marital and health status, culture and ethnicity, and quality of family relationships. Family members must be recognized as highly significant in promoting the health of older clients. The community health nurse should assess the family support system, anticipate future needs and crises, and help families to plan ahead for potential crises. Family members should be encouraged to discuss their concerns and their past and present coping behaviors. The dependent older adult client should be incorporated into the family’s plans as much as possible. The community health nurse can also explore with the family the available resources in the community to meet client and family needs. Common problems encountered in working with an older adult dependent family member include a lack of awareness of services in the community, the need for respite care for families assuming caregiving responsibilities, and the guilt, resentment, and frustration that arise in attempting to provide care and support to the older adult client (see the Ethics in Practice box).

Support Systems for Aging Families in the Community

Because families provide most of the caregiving to older adults, programs for respite and support are needed to improve caregiver coping and to encourage a continued willingness to care for older adults (Administration on Aging, 2011). A variety of support systems are available in the community that might assist in meeting the diverse needs of dependent older adults and their families. The U.S. Administration on Aging (AOA), along with the National Family Caregivers Support Project Program, has developed resource guides to assist families who are involved in caregiving. Some national resources specific to the needs of the older adult population are listed under Community Resources for Practice at the end of the chapter. Older adults who receive social support can function independently for much longer than those who lack these needed services.

Most older adults want to remain in their own home whenever possible, and if this is not possible, most prefer some sort of community-based living arrangement rather than a nursing home. Most (95%) older adults live in the community or in community-based assisted living care. Support services that help to maintain their independence or assist family members to provide care are essential needs in every community.

Long-Term Care

Long-term care refers to a comprehensive range of health, personal, and social services that are coordinated and delivered over a period of time to meet the changing physical, social, and emotional needs of chronically ill and disabled persons. Long-term care may be delivered in the home, in the community, or in an institutional setting (Pratt, 2009). Long-term care services may be provided to clients who exhibit a degree of functional impairment that necessitates assistance with activities of daily living (e.g., bathing, dressing, toileting, eating) or instrumental activities (e.g., meal preparation, housework, shopping). Twenty-five percent of older adults possess at least a mild degree of functional disability or difficulty carrying out personal care and home management activities. A total of 71% of adults 65 or older reported a disability in 2005 (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2008a). Long-term care services focus on assisting the client to maintain independent functioning to the fullest extent possible.

Home Care

Because support systems in the community may be confusing, fragmented, or unknown to the family, the community health nurse must coordinate in-home and community services to meet family health care needs (Cress, 2010). Home care refers to a range of health and supportive services provided in the home to persons who need assistance in meeting health care needs. These services, provided through home health agencies, hospitals, or public health departments, include skilled nursing care, occupational therapy, physical therapy, speech therapy, personal care (e.g., bathing, dressing, and toileting), assistance with meals, meal preparation, and housekeeping. The National Association for Home Care represents the facilities and organizations that provide home care services. Various types of home care services are summarized in Box 28-1. Chapter 31 provides a detailed discussion of home care.

Respite Care

Respite care refers to the provision of temporary, short-term relief to family caregivers (Ganther, 2011). Trained personnel care for the older adult client while the caregiver is away for a period of hours, days, or even weeks. Respite care services may be sponsored by churches, synagogues, nursing homes, home health agencies, volunteer agencies, or for-profit agencies. Care may be provided at home, in institutions (nursing homes, hospitals), or in community-based (adult daycare) centers. One of the most important problems with respite care is cost. Few respite services are reimbursed by private or public health insurance. Paying for respite services out of pocket is often beyond the reach of many families.

Adult Daycare

Adult daycare can serve as an out-of-home form of respite care for family caregivers. Adult daycare centers offer a variety of services for persons who require some assistance but not 24-hour care. The centers may provide health and physical care and recreational, legal, and financial services. Transportation is usually provided to the program. Adult daycare provides a structured program for dependent, community-based older adults who have difficulty performing activities of daily living or who require attention or support during work hours when significant others are not available. Adult daycare programs may provide hot meals, assistance with medications and personal care, counseling, therapy, and recreational activities. The National Institute of Adult Day Care is the national organization representing adult daycare programs. Daycare may be offered through community centers, including local senior citizen centers, religious organizations, retirement homes, nursing homes, or hospitals.

Adult daycare may be classified according to its primary objective. Medical daycare programs are closely affiliated with hospitals or nursing homes and are aimed at providing comprehensive rehabilitation and support services, frequently to clients who have recently been discharged from a hospital. The objective of medical daycare is to restore or maximize physical and mental functioning to the fullest extent possible. Social daycare programs are designed to meet the needs of chronically disabled clients and to provide an opportunity for socialization, recreation, monitoring, and other social services. The goal of these types of programs is to maximize physical and social well-being and to prevent or delay hospitalization (Miller, 2011).

Multipurpose senior centers are community centers that provide lunch programs, home-delivered or congregate meals, socialization, recreational activities, health counseling and screening, information and referral services, and legal and financial counseling services to older adults and their families (Kronkosky Charitable Foundation, 2011). Senior centers attempt to meet the needs of both well and frail older adults in the community. A senior center may also offer adult daycare programs to frail older adult clients. In a senior center, one important nursing role is health education aimed at encouraging health promotion and disease prevention activities.

Community-Based Living Arrangements

Other forms of community-based support systems include foster care, in which the older adult client is cared for in a personal residence by a family licensed through a social service agency to provide meals, housekeeping, and personal care services. Group homes provide shared living arrangements for a group of older adults who are jointly responsible for food preparation, housekeeping, and recreation. Congregate housing describes a variety of group housing options for the older adult in which housing is supplemented by services such as 24-hour security, transportation, recreation, and meals (Miller, 2011). Congregate housing can be an apartment, a single room, or a single room with shared group space. Retirement communities are residential developments designed for older people who may own or rent the units. Recreational and some support services are available. In most retirement communities, residents must contract for health care services on their own.

A life-care (continuous-care) community is a form of retirement housing that provides comprehensive health and social services to the older adult. Residents move from one level (independent living) to others within the community as their health care needs change (Pratt, 2009). For example, an older person might first purchase or rent a home or apartment and then move to congregate living, assisted living, or a nursing home as the need arises. Life-care communities usually require that clients have financial assets to pay for entry into the community.

Nursing Homes

Most older adults do not use nursing home care. Approximately one-third of persons 65 or older will require nursing home care at some time in their lives (Alliance for Health Reform, 2008). The percentage of people 65 years and older living in nursing homes declined from 5.1% in 1990 to 4% in 2008 (Alecxih, 2006; U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2008b). The decline in nursing home use by older adults is attributed to the growth of alternative community caregiving arrangements. Still most nursing home residents are older adults. About 94% of the nursing home population was 65 years and older in 2004 (Alecxih, 2006). Nursing homes provide continuous nursing care, rehabilitation, social activities, supervision, and room and board in state-licensed facilities. Considering nursing home placement is often a painful and traumatic experience for both the client and the family. Families may feel guilt and despair at being unable to maintain their older loved one at home. It is important that the older person be involved as much as possible in the decision-making process. The AARP and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) publish valuable consumer information to assist families in choosing a nursing home that will best meet their needs. Website Resource 28A ![]() contains a sample assessment tool for evaluating nursing homes.

contains a sample assessment tool for evaluating nursing homes.

There are many resources currently available to help with making nursing home choices. Many organizations, such as the AARP, Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and state health departments, are working together to develop clear, concise, comprehensive, and consumer-friendly information profiling nursing homes to inform the public about the quality of care. Using specific checklists or tools along with information gathered during a visit to the nursing home would be most helpful in allowing one to make a good choice.

Sociocultural Influences

As a group, the older adult population represents a diversity of beliefs, values, and cultural practices. Differences in beliefs and values may be attributed to ethnic, cultural, and generational influences. Culture is a learned way of thinking and acting. The behavioral, intellectual, and emotional forms of life expression represent a cultural heritage that is passed on from generation to generation.

A cohort refers to a group of people who share similar characteristics. People born in the same time period (i.e., within approximately 10 years) represent an age cohort. People growing up in different historical eras have lived through similar major life events (e.g., World War II, the Great Depression). These events, however, may affect persons differently depending on their age at the time the events were experienced. Differences in age ranges among older adults may span as much as 40 years, indicating that the older adult population is a heterogeneous group of people who have lived through a diversity of life experiences that have helped to shape them in unique and unpredictable ways. Therefore when working with older adult clients and their families, the community health nurse should approach each person as a unique individual.

The community health nurse can assess the influence of the client’s ethnic and cultural heritage on beliefs, values, and health care practices (refer to Chapter 10 for assessment tools). Specific areas affected by ethnic and cultural orientation include perception of women’s roles, social responses to a growing aging population (changes in legislation, creation of federal programs, emergence of special interest groups), and changes in role performance and opportunities (Betancourt, 2006). Other significant sociocultural influences include family relationships, customs, and habits; religious practices; diet; work and leisure activities; beliefs about pain, illness, and death; forms of verbal and nonverbal expression; and the ethnic and cultural orientation of the surrounding community. Family rituals and practices that are meaningful to the client and do not pose a threat to health or safety should be respected (Ebersole et al., 2008).

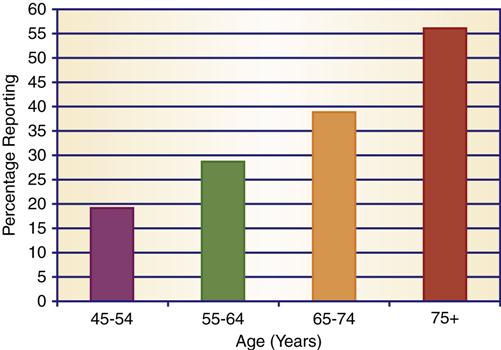

A community with similar cultural practices, beliefs, and values tends to reinforce the client’s and the family’s cultural heritage. Foreign-born older adults who recently immigrated to the United States may have difficulty communicating in English and may live in a community that is foreign to their cultural orientation. Approximately 20% of persons age 5 or older speak a language other than English at home (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2010a) and may live with family members who have difficulty with the English language (Figure 28-2).

Foreign-born residents may require assistance in locating and using needed community resources, including a support network of persons who share their ethnic heritage and reinforce their cultural practices. The community health nurse may also advocate for the needs of these non–English-speaking persons by increasing community awareness of the need for bilingual service providers, publications, and community announcements. Services most acceptable to older adult members of ethnic groups are usually those provided in their community by persons who are conversant in their native language and are sensitive to their cultural practices and beliefs. (See Chapter 10 for a detailed discussion of cultural influences.)

In general, when examining social and cultural influences, the community health nurse requires knowledge of the historical and cultural traditions that have shaped and influenced the personal life experiences of older adult clients and families. These experiences will exert a significant impact on the client’s physical, psychological, social, and economic well-being.

Common health needs of older adults

Four of five older adults experience at least one chronic condition, and many suffer from multiple chronic diseases. Common chronic conditions seen in older adults are the following:

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (USDHHS, 2011), some of the most common complaints of the older adult are diabetes (27%), arthritis (37%), hypertension (69%), and heart conditions (38%). The likelihood of disability increases with age. Disability rates rose with age for both males and females. Disability rates were higher for women (55.9%) than men (47.4%) ages 65 and older (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2006). Persons 65 years or older average 34.6 disability days per year compared with 13.4 days for persons younger than 65 years. Disability days represent days when persons have to reduce their normal activities because of illness or injury, days of confinement to bed, and days lost from work or school.

The prevalence of chronic disease and disability in older adults produces a number of health care needs. Preventive care is also needed for older adults who are healthy to maintain wellness and prevent the onset of illness or disability. The community health nurse should encourage such health promotion behaviors as a balanced diet, regular exercise, stress management, routine medical and dental evaluations, monthly breast or testicular self-examination, annual mammography, and influenza (annually) and pneumonia (one time only) immunizations. Chapters 18 and 19 provide an in-depth discussion of health promotion and screening.

Nutritional Needs

Nutritional needs in older adults may be affected by normal physiological changes associated with aging and psychosocial and environmental factors that affect nutrition (Box 28-2). Dietary planning should take into consideration cultural preferences, religious observances, behavioral patterns (e.g., timing of meals), and special dietary needs (e.g., low-fat, low-cholesterol, diabetic, low-salt). Eliciting a diet history may help the community health nurse to identify dietary patterns and habits. General nutrition education should stress adherence to a balanced diet; maintenance of ideal body weight; limited intake of alcohol, fats, and sugars; increased intake of dietary fiber; and avoidance of excessive salt intake. Most older adults are deficient in vitamin D intake, and therefore a calcium supplement would be helpful (Mahan & Escott-Stump, 2008).

Decreases in hearing, vision, and taste may diminish food appeal. In addition, clients may be unwilling to eat in noisy, public places. When eating out, quiet, well-lit dining areas should be sought to enhance the dining experience.

Decreases in intestinal motility may predispose clients to constipation and overuse of laxatives. Fluid and fiber should be incorporated into the diet to compensate for decreases in intestinal motility. Thirst sensation may be diminished, so adequate water intake (2200 to 2900 ml/day) should be encouraged and monitored (Campbell, 2007). For clients who prefer not to cook for themselves or who have difficulty getting to the store, the community health nurse may wish to investigate home delivery services provided through neighborhood groceries, home-delivered meal services (e.g., Meals on Wheels), or congregate eating programs. The local senior center may provide transportation for shopping or “eating together” programs in which seniors gather for a hot meal in a group setting. Clients experiencing financial difficulties may be eligible for the federal food stamp program. Nutritional information for seniors is available through the National Institute on Aging and the AARP.

Medication Use

Older adults consume approximately 34% of all prescription medication and 40% of over-the-counter medication (Randall & Bruno, 2008). Prescription drug costs increased by 10% each year from 1991 to 2001 and increased 9.1% in 2009 (Dyson, 2010; PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2006). The rising cost of prescription drugs is a hardship for many older adults, especially those who have limited income sources. This concern has led to passage of a prescription drug plan for Medicare (see Box 28-4 later in this chapter, as well as Chapters 3 and 4).

The following conditions place older clients at a higher risk for adverse drug reactions:

Older adults usually take drugs over long periods for chronic conditions. Approximately 25% to 50% of older adults who take prescription medications are noncompliant (Miller, 2011). In one study of 17,000 older Medicare beneficiaries, 52.1% reported medication nonadherence, with 26.3% reporting that nonadherence was related to cost (Wilson et al., 2007). The reasons for noncompliance are numerous and include the following:

• Lack of knowledge of the reason for taking medications or the nature of the illness

• Conflicts with cultural or religious beliefs

• Sense of hopelessness about getting better

• Inaccessibility of pharmacy services

• Inability to open drug container because of sensory-motor impairments

• Desire to avoid unpleasant side effects

In addition to failing to take medication, older adults often use medication inappropriately. They may continue to use outdated or discontinued medication or share pills with others. Many fail to report the use of over-the-counter drugs to their physician, a failure that could result in adverse drug reactions with prescribed medications. Approximately 82% of older adults use over-the-counter medication (Miller, 2011). Common pain relievers and dietary supplements are the most common over-the-counter drugs used by older adults (Qato et al., 2008).

Drug misuse may occur through errors in prescription, the use of prescription drugs without physician supervision, or physician over-prescription. In addition, lack of knowledge of how to take medications properly, self-medication without physician consultation, or receiving medications from multiple physicians without each provider’s knowledge may contribute to drug misuse. Age- and disease-related conditions and multiple drug regimens also compound the problem and may lead to adverse drug reactions or drug overdose (Glaser & Rolita, 2009).

To improve client compliance, the community health nurse working with the older adult client should assess all prescription and over-the-counter drugs in use, including vitamin and mineral supplements, by obtaining a thorough drug history. Older adult clients should be monitored for adverse drug reactions, potential interactions between drugs, and compliance with prescribed regimens. The community health nurse should teach the client and family about the purpose, use, appropriate dosage, and side effects of all drugs. Instructions should be given verbally and in writing to facilitate retention of information. For clients with memory impairment, a calendar or schedule may be developed for taking medications; times for taking medications may be associated with daily activities, such as meals or bedtime (Ebersole et al., 2008).

The client may be advised to select pharmacies that are able to monitor the client’s complete medication profile and alert the client and health care provider to potential adverse drug interactions. Providers are also responsible for explaining drug use and seeking validation of client understanding. Clients may request large-print medicine labels to facilitate readability and flip-off (versus child-proof) caps to allow for ease of opening. The community health nurse may also investigate pharmacies that offer discounts to senior citizens and generic drugs to decrease the cost of medications.

In addition to medication misuse because of lack of knowledge or physical or cognitive impairment, the older adult client may abuse drugs in an attempt to cope with depression and loss. Substance abuse is difficult to identify in the older adult client, because family members may attempt to protect the client by covering up the problem. The problem may become visible only when the behavior of a person living alone begins to draw the attention of others. For example, neighbors may become concerned when basic home repairs are not made, or family members, on visiting the client, may find their loved one unkempt or poorly nourished. The community health nurse can develop outreach programs to reach older persons who are drug-dependent and to educate the public and health professionals about the unique causes and manifestations of substance misuse and abuse in the older adult population. (See Chapter 25 for a detailed discussion of substance abuse in the community.)

Mobility

Adults 65 years and older are more likely to experience a fall-related mortality than are younger age groups. Falls are the most frequent injury and cause of hospital admissions for trauma among older adults (USDHHS, 2011). Over 90% of hip fractures in older adults are caused by falls (CDC, 2011). Falls account for 40% of the admissions to long-term care facilities (American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2009). The risk for falling is increased in older adults because of confusion, disturbances in gait, alterations in musculoskeletal functioning, medication side effects, unfamiliarity with new surroundings, poor eyesight, and orthostatic hypotension, which may produce dizziness and syncope (Gleberzon & Hyde, 2006).

Approximately 19.3% of persons older than 75 years of age and 11.8% of persons between the ages of 65 and 74 reported activity limitations from arthritis (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2005). The loss of muscle strength, painful joints, and stiffness affect gait and limit range of motion (Ebersole et al., 2008).

Osteoporosis is prevalent in postmenopausal women and in men older than 80 years. Estrogen deficiency accelerates the loss of bone mass associated with aging and may lead to back pain, deformity, or loss of height because of osteoporotic bone changes. Clients with osteoporosis are at a greater risk for sustaining fractures with little or no trauma.

Activity limitations imposed by chronic illness further compromise mobility in the older adult client. Approximately 62.2% of adults 65 years and older have a low level of overall physical activity and did not engage in recommended amounts of physical activity (USDHHS, 2011). The U.S. Census Bureau (2012a) reports that over 23% of the 65 and older population have difficulty walking.

The community health nurse may assist the older adult client to maintain flexibility, muscle strength, and bone mass through counseling about sound nutritional practices and through encouraging adoption of exercise programs that strengthen muscle and improve cardiovascular function. Exercise becomes especially important in later life because it can slow, stop, or reverse physical decline (Melov et al., 2007). Walking, calisthenics, water aerobics (calisthenics performed in a swimming pool), and cycling on a stationary bicycle are examples of activities that provide an excellent form of exercise with a minimum degree of stress on joints. Exercise groups can improve social interaction. Walking is the most popular form of physical activity for older adults and provides increased social interaction and an increased sense of well-being (Ebersole et al., 2008). Almost half of persons over 65 report they engage in no physical activity (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010b).

All five senses become less acute with age. Sensory impairment affects both perception and the ability to move around in the environment. Approximately 28.3% of seniors over the age of 75 have one or more sensory disabilities (Brault, 2009). One of every 20 Americans 85 years of age or older is legally blind. Many older adults need glasses and have difficulty with night vision. Thirteen percent of persons age 65 and older report having trouble seeing even with glasses (USDHHS, 2011).

The leading causes of blindness in persons 65 years of age and older include glaucoma (increased intraocular pressure), macular degeneration (which leads to loss of central vision), cataracts (a clouding or opacity of the lens of the eye), and diabetic retinopathy. These conditions may lead to a decrease in visual acuity, a decrease in depth perception, a decrease in peripheral vision, a decreased tolerance to glare, and a decreased ability of the lens of the eye to focus on objects. Visual and hearing impairments may mask warning signs in the environment, predisposing older adults to accidental injury. When caring for clients who have sensory impairments that may compromise mobility, the community health nurse should identify hazards in the environment, teach the client and the family about home safety, and promote an environment that encourages both independence and safety (Ebersole et al., 2008). Many environmental hazards are associated with falls or near falls, including attempting to negotiate in the dark and walking on slippery floor coverings and uneven walking surfaces. Costello and Edelstein (2008) reported that falls could be reduced by improving positional stability, alertness, and attention in older adults.

Information about transportation services for older adult clients may be obtained by contacting the local office on aging or the local senior center. The area agency on aging may contract with a local taxi company to provide transportation to seniors at a discounted rate. In some localities, mass transit buses and subways receive federal funding from the Department of Transportation and provide discounted rates for senior citizens. These discounts may be available on a 24-hour basis or restricted to non–rush hour times. Medicare cards may enable the older adult client to ride at half fare, or reduced fare cards may be obtained from the local office on aging. The American Red Cross may provide emergency transportation when an older adult client is discharged from a hospital or emergency department. Local governments or community agencies may also sponsor “senioride” programs, which provide door-to-door transportation to older adults at a minimal cost.

Social Isolation

Thirty-seven percent of people 65 or older live alone (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2012b). Older women are more likely to live alone than are men. Seventy-eight percent of men 65 to 74 years were married and living with their spouse, whereas only 55.9% of women in the same age group did so (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012c). Living alone, coupled with the prevalence of sensory-perceptual and mobility impairments, cognitive impairment, and chronic illness, places the older adult client at a higher risk for social isolation. It is imperative that community health nurses assess the older adult’s social support network, including family, peers, church-related and other groups, professional caregivers, and other more informal caregivers. Social support through friends, relatives, and acquaintances can be of great value in giving life meaning. Low levels of social support are associated with higher rates of health problems.

Mental Health Disorders

Social isolation may be a symptom of a mental health disorder. Depression and dementia are the two most common mental health disorders in older adults.

Depression

It is estimated that 10% to 14% of older adults may experience depression and depression increases as functional ability becomes limited (National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 2011). Depression may be characterized by a persistent sad or depressed mood (i.e., at least 2 weeks), loss of pleasure in previously enjoyable activities, impaired thinking and concentration, or recurrent thoughts of death or suicide. Depressed clients may also experience insomnia or hypersomnia (increase in sleep), early morning awakening, loss of interest in activities, feelings of guilt, fatigue, loss of appetite, weight gain or loss, agitation, and feelings of helplessness or hopelessness (Miller, 2011).

Geriatric depression may develop as a result of actual or perceived losses, environmental stresses, neurological or endocrine disorders, adverse effects of medication, infection, or alcohol consumption (Hutman et al., 2005; NIMH, 2011). Treatment of depression in older adults may be delayed or never pursued because sadness and loss are often thought to be normal consequences of aging. Depression may also be inappropriately regarded as a normal consequence of senility. Depression may not be identified early in clients who live alone and have few social contacts. Older adult depressed clients may report anxiety, physical symptoms such as chronic pain or worries about the body, or a loss of concentration and difficulties with memory.

Older adults account for nearly 12% of the population but commit 16% of the suicides (NIMH, 2011). Men accounted for 80% of suicides among persons ages 65 years and older in 2007 and actually have higher suicide rates than men in all other age groups (USDHHS, 2011). Older adults who live alone often perceive themselves as friendless, have few meaningful attachments to the community, have little social support, and are more vulnerable to psychiatric illness, depression, and suicide. Warning signs of suicidal intent include verbal clues indicating a desire to commit suicide (e.g., “others would be better off without me”), behavioral clues (such as getting personal affairs in order or changing one’s will), and situational clues (e.g., significant loss, death of spouse, diagnosis of illness, recent undesired move, family conflict) (Smith & Jaffe, 2007). Detecting suicide ideation in older adults may be more difficult because they do not provide as many verbal cues as younger adults (Miller, 2011).

It is important for the community health nurse to monitor for signs and symptoms of depression, to be alert to subtle differences in behavior, and to refer clients to the appropriate resources for medical evaluation, counseling, and support. Social interactions seem to alleviate or reduce the risk for depression (Lyness et al., 2006).

Clients who are struggling with feelings of worthlessness and low self-esteem may also benefit from therapeutic reminiscence. The notion of reminiscence or life review involves a reflection on past life experiences with the goal of building self-esteem and understanding, stimulating thinking, transmitting a cultural heritage, and finding meaning, worth, and acceptance in life. The use of group reminiscence in nursing homes has reduced the level of depression in participating residents (Ebersole et al., 2008).

Reminiscence is, in essence, communicating comforting memories (Ebersole et al., 2008). A story recounts both the joys and struggles of human experience. Persons may be assisted in telling their stories through involvement in the following activities that invite storytelling:

• Sharing memorabilia and family pictures

• Participating in reminiscence support groups

• Constructing family trees or scrapbooks

• Writing or audio recording a personal autobiography

• Creating safe, supportive environments that permit disclosure

• Demonstrating a nonjudgmental, open, accepting attitude to the client’s disclosures

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree