Nutritional Support

Objectives

• Explain the differences between enteral nutrition and parenteral nutrition.

• Describe the routes for enteral feedings.

• Discuss examples of enteral solutions, and explain the differences.

• Explain the advantages and differences of the methods used to deliver enteral nutrition.

• Describe the complications that may occur with use of enteral nutrition and parenteral nutrition.

• Discuss the nursing interventions for patients receiving enteral nutrition and parenteral nutrition.

Key Terms

bolus, p. 245

continuous feedings, p. 246

cyclic method, p. 246

enteral nutrition, p. 244

gastrostomy tube, p. 244

hyperalimentation, p. 244

intermittent enteral feedings, p. 245

intermittent infusion, p. 246

jejunostomy tube, p. 244

nasogastric tube, p. 244

nutritional support, p. 244

parenteral nutrition, p. 244

total parenteral nutrition, p. 244

Valsalva maneuver, p. 249

Nutrients are needed for cell growth, cellular function, enzyme activity, carbohydrate-fat-protein synthesis, muscular contraction, wound healing, immune competence, and gastrointestinal (GI) integrity. Inadequate nutrient intake can result from surgery, trauma, malignancy, and other catabolic illnesses. Without adequate nutritional support, protein catabolism (breakdown), malnutrition, and diminished organ functioning will affect the GI, hepatic, renal, cardiac, and respiratory systems. The functioning of the immune system also is decreased.

Patients who are well nourished can usually tolerate a lack of nutrients for 14 days without major health problems. However, patients who are critically ill may only tolerate a lack of nutrient support for a short period (a few days to a week) before signs of impaired organ function, infection, or morbidity result. If nutritional support is started within hours of an injury, as in the cases of severe trauma or burns, recovery is more rapid. When injury is a result of minor surgery, no severe bodily harm results from lack of nutritional support for days. For both the critically ill and for patients with major injuries, early nutritional support improves intestinal and hepatic blood flow and function, enhances wound healing, decreases the occurrence of infection, and improves the general outcome of the health situation. “Early fed” injured patients have a positive nitrogen balance and less chance for bacterial infections; thus, they also have a decrease in institutional length of stay.

Dextrose 5% in water (D5W), normal saline, and lactated Ringer’s solution are not forms of nutritional support (supporting healthy tissue growth and wellness), although these solutions do provide fluids and some electrolytes. A patient requires 2000 calories per day; critically ill patients may require 3000 to 5000 calories per day. For individuals with extensive burns, the caloric need could be even greater. Patients who receive nothing by mouth (NPO) for an extended period become malnourished. Delayed nutritional support by as little as 5 days for a patient experiencing trauma or neurologic damage (e.g., cervical fracture) could hamper wound healing and increase the risk for developing an infection.

There are two routes for administering nutritional support: enteral and parenteral. Enteral nutrition, which involves the GI tract, can be given orally or by feeding tubes (tube feeding). If the patient can swallow, nutrient preparations can be taken by mouth; if the patient is unable to swallow, a tube is inserted into the stomach or small intestine. ![]() Parenteral nutrition involves administering high-caloric nutrients through large veins, for example, the subclavian vein. This method is called total parenteral nutrition (TPN), hyperalimentation (HA), or intravenous hyperalimentation (IVH). Parenteral nutrition is more costly (approximately three times more expensive) than enteral nutrition, and the benefits are not significant. In fact with TPN there is a higher infection rate than with enteral nutrition. The use of TPN does not promote effective GI integrity, hepatic function, or body weight gain, as enteral nutrition does. Enteral feedings require a functioning GI tract. TPN becomes necessary when the GI tract is incapacitated due to uncontrolled vomiting, malabsorption, or intestinal obstruction. TPN may also be necessary in patients with a high risk for aspiration or to supplement inadequate oral intake. TPN is also used for GI rest from exacerbations of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis; elemental nutrition absorbed by the duodenum and jejunum may be used for exacerbation of Crohn’s disease involving the terminal ilium or ascending colon. TPN is also needed in conjunction with enteral feedings for patients with multiple trauma, including burn patients, when metabolic demand exceeds the number of calories that can be delivered by the GI system.

Parenteral nutrition involves administering high-caloric nutrients through large veins, for example, the subclavian vein. This method is called total parenteral nutrition (TPN), hyperalimentation (HA), or intravenous hyperalimentation (IVH). Parenteral nutrition is more costly (approximately three times more expensive) than enteral nutrition, and the benefits are not significant. In fact with TPN there is a higher infection rate than with enteral nutrition. The use of TPN does not promote effective GI integrity, hepatic function, or body weight gain, as enteral nutrition does. Enteral feedings require a functioning GI tract. TPN becomes necessary when the GI tract is incapacitated due to uncontrolled vomiting, malabsorption, or intestinal obstruction. TPN may also be necessary in patients with a high risk for aspiration or to supplement inadequate oral intake. TPN is also used for GI rest from exacerbations of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis; elemental nutrition absorbed by the duodenum and jejunum may be used for exacerbation of Crohn’s disease involving the terminal ilium or ascending colon. TPN is also needed in conjunction with enteral feedings for patients with multiple trauma, including burn patients, when metabolic demand exceeds the number of calories that can be delivered by the GI system.

Solutions for enteral nutrition and parenteral nutrition include amino acids, carbohydrates, electrolytes, fats, trace elements, and vitamins.

Enteral Nutrition

Enteral nutrition requires adequate small bowel function with digestion, absorption, and GI motility. To determine whether there is a lack of GI motility, the nurse assesses for abdominal distention and a decrease or absence of bowel sounds and notes if the patient has a bowel movement.

In critically ill patients, frequently there is a decrease or absence in gastric emptying time; then TPN may be necessary. The preferred method for nutritional support is enteral feedings for patients with intact gastric emptying and with a decreased risk of aspiration.

Routes for Enteral Feedings

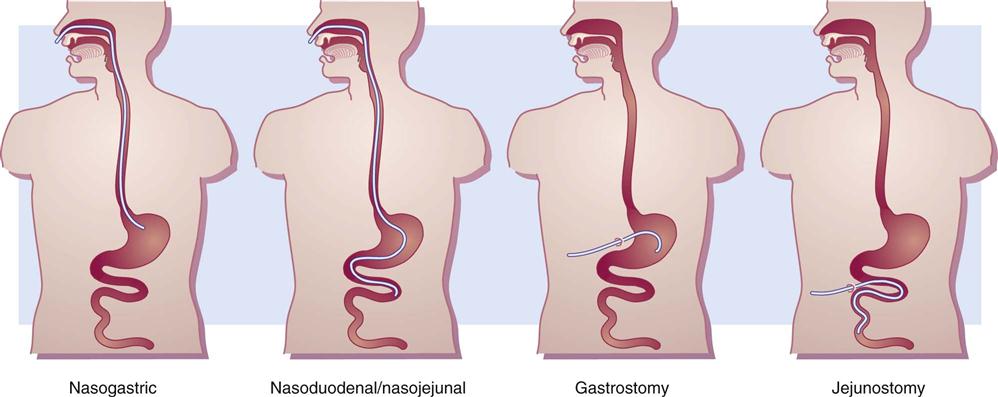

The routes for enteral feedings include: oral, gastric by nasogastric tube or gastrostomy tube, and small intestinal by nasoduodenal/nasojejunal or jejunostomy tube. Use of a nasogastric tube through oral (mouth) or nasal cavities is the most common route for short-term enteral feedings. The gastrostomy, nasoduodenal/nasojejunal, and jejunostomy tubes are used for long-term enteral feedings. Figure 17-1 displays the four types of GI tubes used for enteral feedings. If aspiration is a concern, the small intestinal route is suggested.

Enteral Solutions

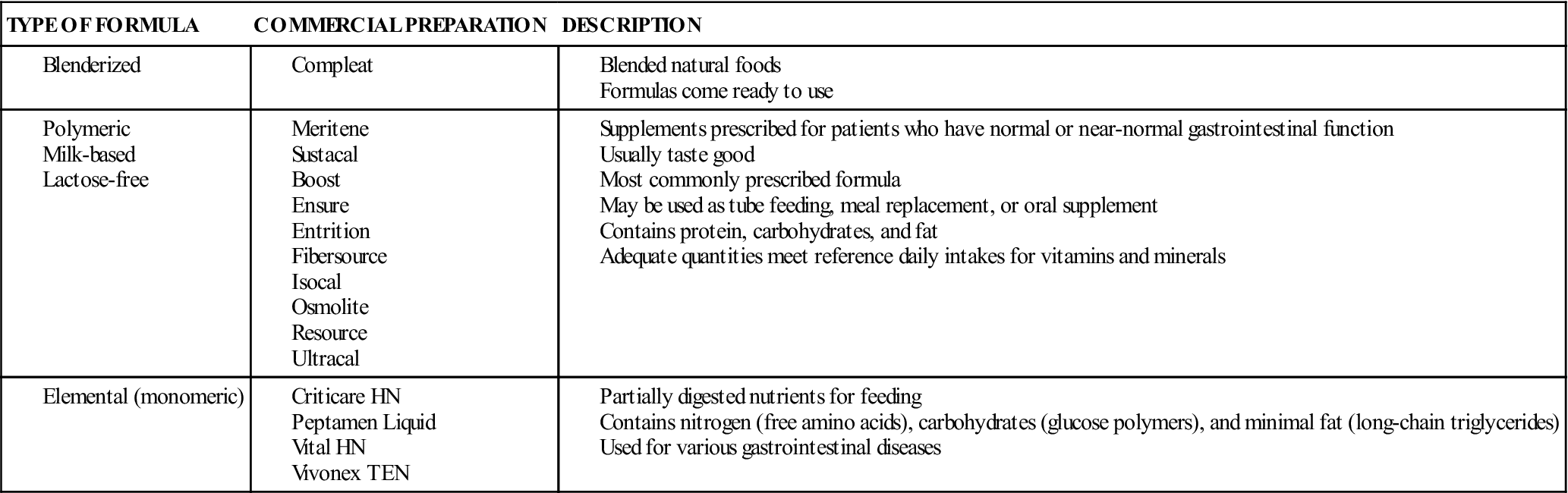

Several types of liquid formulas are available for enteral feedings. These solutions differ according to their various nutrients, caloric values, and osmolality. The three groups of solutions for enteral nutrition are blenderized; polymeric (milk-based and lactose-free); and elemental or monomeric. Examples of commercial preparations are listed according to their groups in Table 17-1. Components of the enteral solutions include (1) carbohydrates in the form of dextrose, sucrose, lactose, starch, or dextrin (the first three are simple sugars that can be absorbed quickly); (2) protein in the form of intact proteins, hydrolyzed proteins, or free amino acids; and (3) fat in the form of corn oil, soybean oil, or safflower oil (some have a higher oil content than others). With all enteral nutrition, sufficient water to maintain hydration is essential.

TABLE 17-1

COMMERCIAL PREPARATIONS FOR ENTERAL FEEDING

Blended formulas for enteral solutions are liquid in consistency, so they are able to pass through the tube. These are individually prepared based on the patient’s nutritional need. Frequently, baby food is used with liquid added. If food particles are too large, the tube can become clogged.

The two groups of polymeric solutions are milk based and lactose free. Most milk-based polymeric preparations come in powdered form to be mixed with milk or water. Many of these solutions do not provide complete nutritional requirements unless given in large amounts. Frequently they are used as a supplement to meet nutritional needs. Lactose-free polymeric solutions are commercially prepared in liquid form for replacement feedings. Many of these solutions are isotonic (300 to 340 mOsm/kg water), and the breakdown of nutrients includes 50% carbohydrates, 15% protein, 15% fat, and 20% other nutrients. Examples of polymeric solutions include Ensure, Isocal, and Osmolite. These solutions provide 1 calorie per milliliter of feeding.

Characteristics of the formula may be targeted to treat a specific group of disorders. For those with diabetes mellitus, Glucerna and Diabetic Resource (low-carbohydrate, high-fat, lactose-free products) are most helpful. NutriHep (low-fat, lactose-free product) is recommended to treat hepatic disorders. For individuals with pulmonary disorders, Pulmocare or Respalor (low-carbohydrate, high-fat products) are commonly prescribed. Nepro and Novasource Renal (low-fat amino acids, water-soluble vitamins) are used to treat those with renal disorders.

For partial GI tract dysfunction, the elemental or monomeric solutions are useful (e.g., Peptinex DT). They are available in powdered and liquid forms. The nutrients from these solutions are rapidly absorbed in the small intestine. They are more expensive than the other enteral solutions.

Methods for Delivery

Enteral feedings may be given by bolus, intermittent drip or infusion, continuous drip, or cyclic infusion. The bolus method was the first method used to deliver enteral feedings. With the bolus method, 250 to 400 mL of solution is rapidly administered through a syringe or funnel into the tube four to six times a day. This method takes about 10 minutes each feeding, and may not be tolerated well by the patient because a massive volume of solution is given in a short period. This method can cause nausea, vomiting, aspiration, abdominal cramping, and diarrhea, but a healthy patient can normally tolerate the rapidly infused solution. This method is usually reserved for ambulatory patients.

Intermittent enteral feedings are administered every 3 to 6 hours over 30 to 60 minutes by gravity drip or pump infusion. At each feeding, 300 to 400 mL of solution is usually given. A feeding bag is commonly used. Intermittent infusion is considered an inexpensive method for administering enteral nutrition.

Continuous feedings are prescribed for the critically ill or for those who receive feedings into the small intestine. The enteral feedings are given by an infusion pump such as the Kangaroo set to control the flow at a slow rate over 24 hours. Approximately 50 to 125 mL of solution is infused per hour.

The cyclic method is another type of continuous feeding that is infused over 8 to 16 hours daily (day or night). Administration during daytime hours is suggested for patients who are restless or for those who have a greater risk for aspiration. The nighttime schedule allows more freedom during the day for patients who are ambulatory.

Complications

Dehydration can occur if an insufficient amount of water is given with or between feedings. Some enteral solutions are hyperosmolar and can draw water out of the cells to maintain serum iso-osmolality.

Aspiration pneumonitis is the major complication of enteral nutrition and may occur if the patient is fed while lying down or is unconscious. The head of the bed should be elevated at least 30 to 45 degrees. The nurse should check for gastric residual by gently aspirating the stomach contents before administering the next enteral feeding and every 4 hours minimum between feedings.

One of the major problems of enteral feeding is diarrhea. This could be caused by rapid administration of feeding, high caloric solutions, malnutrition, GI bacteria (Clostridium difficile), and drugs. Antibacterials and drugs that contain magnesium (e.g., antacids [Maalox], sorbitol [used as filler for certain drugs]) are associated with the occurrence of diarrhea. Many oral liquid drugs are hyperosmolar and tend to pull water into the GI tract and cause diarrhea.

Diarrhea can usually be managed or corrected by decreasing the rate of infusion of the enteral solution, diluting the solution, changing the solution, discontinuing the drug, increasing the patient’s daily water intake, or administering enteral solution containing fiber.

Monitoring is essential when the patient is receiving enteral nutrition. Recommended parameters to monitor include: blood chemistry; BUN, creatinine, and electrolytes; glucose; triglycerides; serum proteins; I&O; and weight. Frequency of monitoring is patient dependent and more frequent at initiation of enteral nutrition.

Enteral Safety

The American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) initiated the Be A.L.E.R.T. campaign to promote safe tube feeding:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree