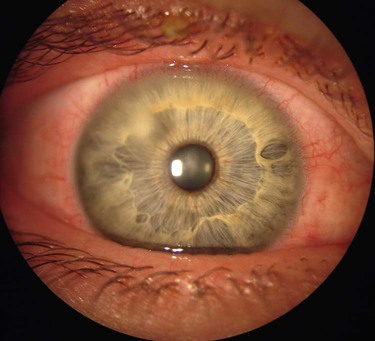

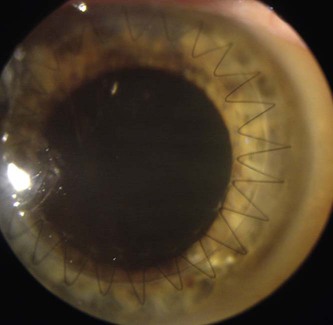

1. Compare and contrast the types of refractive errors and appropriate corrections. 2. Describe the etiology and collaborative care of extraocular disorders. 3. Explain the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing management and collaborative care of the patient with selected intraocular disorders. 4. Discuss the nursing measures that promote the health of the eyes and ears. 5. Elaborate on the general preoperative and postoperative care of patients undergoing surgery of the eye or ear. 6. Summarize the action and uses of drug therapy for treating problems of the eyes and ears. 7. Explain the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and collaborative management of common ear problems. 8. Compare the causes, management, and rehabilitative potential of conductive and sensorineural hearing loss. 9. Explain the use, care, and patient teaching related to assistive devices for eye and ear problems. 10. Describe the common causes and assistive measures for uncorrectable visual impairment and deafness. 11. Describe the measures used to assist the patient in adapting psychologically to decreased vision and hearing. eTABLE 22-1 OCULAR MANIFESTATIONS OF SYSTEMIC DISEASES CMV, Cytomegalovirus; CN, cranial nerve; IOP, intraocular pressure. eTABLE 22-2 PATIENT & CAREGIVER TEACHING GUIDE Presbyopia is the loss of accommodation associated with age. This condition generally appears at about age 40. As the eye ages, the lens becomes larger, firmer, and less elastic. These changes, which progress with aging, result in an inability to focus on near objects.1 In general, you need to know whether the patient wears contact lenses, the pattern of wear (daily versus extended), and care practices. Shining a light obliquely on the eyeball can help visualize a contact lens. Contact lenses are associated with microbial keratitis, a severe sight-threatening complication. Risk factors for keratitis include poor hand cleaning, poor lens case hygiene, and inadequate lens cleaning.2 Teach the patient the importance of following recommended cleaning practices and reporting redness, sensitivity, vision problems, and pain to the eye care professional. Instruct the patient to remove contact lenses immediately if any of these problems occur. Laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) may be considered for patients with low to moderately high amounts of myopia or hyperopia, with or without astigmatism. The procedure first involves using a laser or surgical blade to create a flap in the cornea. The flap is folded back on the middle section, or stroma, of the cornea.3 Pulses from a computer-controlled laser vaporize a part of the stroma. The flap is then repositioned, adhering on its own without sutures in a few minutes. In the United States, 6.5 million people over age 65 have severe visual impairment, which is defined as the inability to read newsprint even with glasses.4 Of those individuals, 9% have no useful vision, and the remaining 91% are considered partially sighted. The partially sighted individual may still have significant visual abilities. The patient with either total or functional blindness is considered legally blind. Legal blindness refers to central visual acuity of 20/200 or less in the better eye with correction, or a peripheral visual field of 20 degrees or less. It is estimated that about 1.3 million people in the United States are legally blind. Almost all blindness in the United States is the result of common eye diseases, including cataracts, glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration, and diabetic retinopathy. Less than 4% of blindness is the result of injuries.4 In working with the visually impaired patient, remember that a person classified as legally blind may have some useful vision. Rehabilitation after partial or total loss of vision can foster independence, self-esteem, and productivity. Know what services and devices are available for the partially sighted or blind patient, and make appropriate referrals. For the legally blind patient the primary resource for services is the state agency for rehabilitation of the blind. Legally blind individuals are eligible for federal and state assistance and income tax benefits. A list of agencies that serve the partially sighted or blind patient is available from the American Foundation for the Blind (www.afb.org). Many of these agencies are listed in the resources section at the end of the chapter. A wide range of newer technologies are available to assist people with low vision.5 These devices include desktop video magnification/closed circuit units, electronic hand-held magnifiers, text-to-speech scanners (material read aloud to you), E-readers, and computer tablets (material read aloud, magnification, image zooming, brighter screen, voice recognition). Many of these devices require some training by an assistive technology professional. Encourage patients to practice with the technologic device to ensure they can use it successfully. Approach magnification is a simple way to enhance the patient’s residual vision. Recommend that the patient sit closer to the television or hold books closer to the eyes. Contrast enhancement techniques include watching television in black and white, using a black felt-tip marker, and using contrasting colors (e.g., a red stripe at the edge of steps or curbs). Increased lighting can be provided by halogen lamps, direct sunlight, or gooseneck lamps that can be aimed directly at the reading material or other near objects.6 Large type is often helpful, especially in conjunction with other optical or nonoptical vision enhancements. Although the eyes are well protected by the bony orbit and fat pads, everyday activities can result in ocular trauma. In the United States an estimated 2.5 million eye injuries occur each year. Of those injured, more than 10% will lose useful vision in the affected eye. Table 22-1 outlines emergency management of the patient with an eye injury. The most common ocular injuries in the United States occur in the home due to gardening, power tool use, and home repair work.7 Sport and work-related injuries are additional causes of eye trauma. EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT An external hordeolum (commonly called a sty) is an infection of the sebaceous glands in the lid margin (Fig. 22-1). The most common bacterial infective agent is Staphylococcus aureus. A red, swollen, circumscribed, and acutely tender area develops rapidly. Instruct the patient to apply warm, moist compresses at least four times a day until it improves. This may be the only treatment necessary. If it tends to recur, teach the patient to perform lid scrubs daily. In addition, appropriate antibiotic ointments or drops may be indicated. Blepharitis is a common chronic bilateral inflammation of the lid margins.8 The lids are red rimmed with many scales or crusts on the lid margins and lashes. The patient may primarily complain of itching but may also experience burning, irritation, and photophobia. Conjunctivitis may occur simultaneously. Acute bacterial conjunctivitis (pinkeye) is a common infection. Although it occurs in every age-group, epidemics are common among children because of their poor hygienic habits. S. aureus is the most common cause. The patient with bacterial conjunctivitis may complain of discomfort, pruritus, redness, and a mucopurulent drainage.9 Although this typically occurs initially in one eye, it generally spreads to the unaffected eye. It is usually self-limiting, but treatment with antibiotic drops (e.g., besifloxacin [Besivance]) shortens the course of the disorder. Trachoma is a chronic conjunctivitis caused by Chlamydia trachomatis (serotypes A through C). It is a major cause of blindness worldwide. An estimated 84 million people have active disease in need of treatment if blindness is to be prevented, with 8 million people already living with irreversible vision loss.10 Antiviral treatments include trifluridine drops (Viroptic), oral acyclovir (Zovirax), and topical vidarabine (Vira-A) ointment.11 Therapy may also involve corneal debridement. Topical corticosteroids are usually contraindicated because they contribute to a longer course and possible deeper ulceration of the cornea. Tissue loss caused by infection of the cornea produces a corneal ulcer (infectious keratitis) (Fig. 22-2). The infection can be due to bacteria, viruses, or fungi. Corneal ulcers are often painful, and patients may feel as if there is a foreign body in their eye. Other symptoms can include tearing, purulent or watery discharge, redness, and photophobia. Treatment is generally aggressive to avoid permanent loss of vision. Antibiotic, antiviral, or antifungal eyedrops may be prescribed as frequently as every hour night and day for the first 24 hours. An untreated corneal ulcer can result in corneal scarring and perforation (hole in the cornea). A corneal transplant may be indicated. Keratoconjunctivitis sicca (dry eyes) is a common complaint, particularly of older adults and individuals with certain systemic diseases such as scleroderma and systemic lupus erythematosus. Patients with dry eyes complain of irritation or “sand in my eye” and that the sensation typically worsens through the day. This condition is caused by a decrease in the quality or quantity of the tear film, and treatment is directed at the underlying cause. With decreased tear secretion, the patient may use artificial tears or ointments. In severe cases, closure of the lacrimal puncta may be necessary. Patients with dry eyes associated with dry mouth may have Sjögren’s syndrome (see Chapter 65). The cornea is an optically transparent tissue that allows light rays to enter the eye and focus on the retina, thus producing a visual image. Any wound causes the cornea to become abnormally hydrated and decreases the normal transparency. The treatment for corneal scars or opacities is penetrating keratoplasty (corneal transplant). The ophthalmic surgeon removes the full thickness of the patient’s cornea and replaces it with a donor cornea that is sutured into place (Fig. 22-3). Vision may not be restored for up to 12 months. Newer procedures in which only the damaged cornea epithelial layer is replaced are Descemet’s stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK) and Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK).12 Patients report faster visual recovery with less astigmatism and changes in their glass lens prescription with these surgeries. A cataract is an opacity within the lens. The patient may have a cataract in one or both eyes. If cataracts are present in both eyes, one may affect the patient’s vision more than the other. Almost 22 million Americans ages 40 years and older have cataracts, and by age 80 more than 50% have cataracts. Direct medical costs for cataract treatment are estimated at $6.8 billion annually. Cataract removal is the most common surgical procedure in the United States.13 The patient with cataracts may complain of a decrease in vision, abnormal color perception, and glare. Glare is due to light scatter caused by the lens opacities, and it may be significantly worse at night when the pupil dilates. The visual decline is gradual, but the rate of cataract development varies from patient to patient. Diagnosis is based on decreased visual acuity or other complaints of visual dysfunction. The opacity is directly observable by ophthalmoscopic or slit lamp microscopic examination. As noted earlier, a totally opaque lens creates the appearance of a white pupil. Table 22-2 lists other diagnostic studies that may be helpful in evaluation of a cataract. TABLE 22-2

Nursing Management

Visual and Auditory Problems

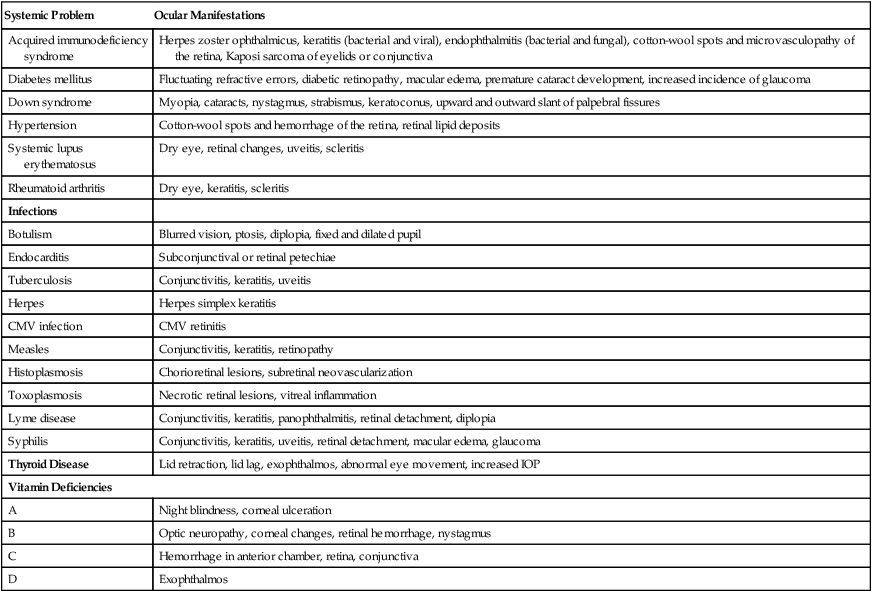

Systemic Problem

Ocular Manifestations

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus, keratitis (bacterial and viral), endophthalmitis (bacterial and fungal), cotton-wool spots and microvasculopathy of the retina, Kaposi sarcoma of eyelids or conjunctiva

Diabetes mellitus

Fluctuating refractive errors, diabetic retinopathy, macular edema, premature cataract development, increased incidence of glaucoma

Down syndrome

Myopia, cataracts, nystagmus, strabismus, keratoconus, upward and outward slant of palpebral fissures

Hypertension

Cotton-wool spots and hemorrhage of the retina, retinal lipid deposits

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Dry eye, retinal changes, uveitis, scleritis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Dry eye, keratitis, scleritis

Infections

Botulism

Blurred vision, ptosis, diplopia, fixed and dilated pupil

Endocarditis

Subconjunctival or retinal petechiae

Tuberculosis

Conjunctivitis, keratitis, uveitis

Herpes

Herpes simplex keratitis

CMV infection

CMV retinitis

Measles

Conjunctivitis, keratitis, retinopathy

Histoplasmosis

Chorioretinal lesions, subretinal neovascularization

Toxoplasmosis

Necrotic retinal lesions, vitreal inflammation

Lyme disease

Conjunctivitis, keratitis, panophthalmitis, retinal detachment, diplopia

Syphilis

Conjunctivitis, keratitis, uveitis, retinal detachment, macular edema, glaucoma

Thyroid Disease

Lid retraction, lid lag, exophthalmos, abnormal eye movement, increased IOP

Vitamin Deficiencies

A

Night blindness, corneal ulceration

B

Optic neuropathy, corneal changes, retinal hemorrhage, nystagmus

C

Hemorrhage in anterior chamber, retina, conjunctiva

D

Exophthalmos

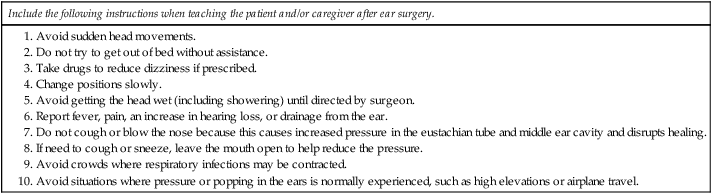

After Ear Surgery

Visual Problems

Correctable Refractive Errors

Nonsurgical Corrections

Contact Lenses.

Surgical Therapy

Laser.

Uncorrectable Visual Impairment

Nursing Management Visual Impairment

Nursing Assessment

Nursing Implementation

Health Promotion.

Ambulatory and Home Care.

Optical Devices for Vision Enhancement.

Nonoptical Methods for Vision Enhancement.

Gerontologic Considerations

Visual Impairment

Eye Trauma

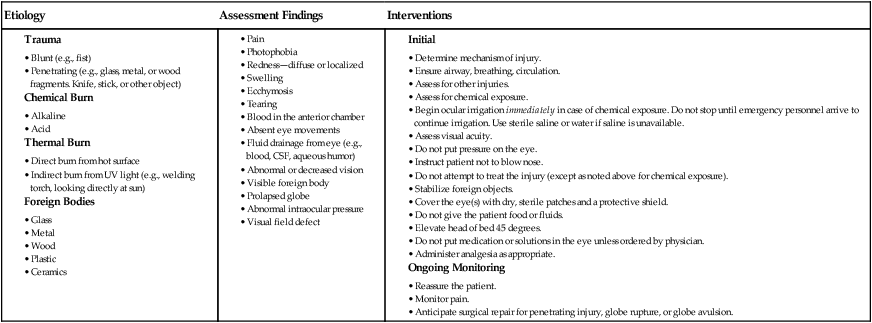

![]() TABLE 22-1

TABLE 22-1

Eye Injury

Extraocular Disorders

Inflammation and Infection

Conjunctivitis

Bacterial Infections.

Chlamydial Infections.

Keratitis

Viral Infections.

Corneal Ulcer.

Nursing Management Inflammation and Infection

Dry Eye Disorders

Corneal Disorders

Corneal Scars and Opacities

Intraocular Disorders

Cataract

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnostic Studies

Nursing Management: Visual and Auditory Problems

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access