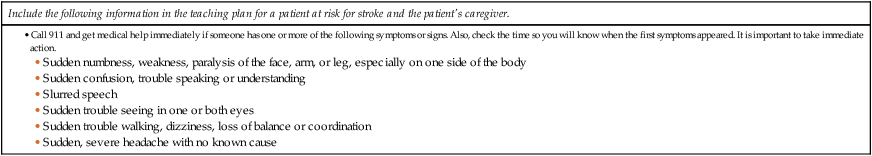

Chapter 58 1. Describe the incidence of and risk factors for stroke. 2. Explain mechanisms that affect cerebral blood flow. 3. Compare and contrast the etiology and pathophysiology of ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes. 4. Correlate the clinical manifestations of stroke with the underlying pathophysiology. 5. Identify diagnostic studies performed for patients with strokes. 6. Differentiate among the collaborative care, drug therapy, and surgical therapy for patients with ischemic strokes and hemorrhagic strokes. 7. Describe the acute nursing management of a patient with a stroke. 8. Describe the rehabilitative nursing management of a patient with a stroke. 9. Explain the psychosocial impact of a stroke on the patient, caregiver, and family. The terms brain attack and cerebrovascular accident (CVA) are also used to describe stroke. The term brain attack communicates the urgency of recognizing the clinical manifestations of a stroke and treating this as a medical emergency, as would be done with a heart attack (Table 58-1). After the onset of a stroke, immediate medical attention is crucial to decrease disability and the risk of death. TABLE 58-1 PATIENT & CAREGIVER TEACHING GUIDE • Call 911 and get medical help immediately if someone has one or more of the following symptoms or signs. Also, check the time so you will know when the first symptoms appeared. It is important to take immediate action. Source: American Stroke Association: Learn to recognize a stroke, 2009. Retrieved from www.strokeassociation.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=1020. Stroke is a major public health concern. An estimated 7 million people over the age of 20 in the United States have had a stroke, with 795,000 individuals affected annually.1 With an aging population, a further increase in the incidence of stroke can be expected. However, stroke can occur at any age. About 28% of strokes occur in people younger than 65 years old.2 Stroke is the fourth most common cause of death in the United States, behind cancer, heart disease, and lung disease. More than 275,000 deaths occur annually from stroke. Women are more likely than men to die from a stroke because of the greater number of women over age 65.1 Stroke is the leading cause of serious, long-term disability. Of those who survive a stroke, 50% to 70% are functionally independent, and 15% to 30% live with permanent disability. Twenty-six percent require long-term care after 3 months.3 Common long-term disabilities include hemiparesis, inability to walk, complete or partial dependence for activities of daily living (ADLs), aphasia, and depression. In addition to the physical, cognitive, and emotional impact of the stroke on the stroke survivor, the stroke affects the lives of the stroke victim’s caregiver and family.4 A stroke is a lifelong change for both the stroke survivor and the family. Blood is supplied to the brain by two major pairs of arteries: the internal carotid arteries (anterior circulation) and the vertebral arteries (posterior circulation). The carotid arteries branch to supply most of the frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes; the basal ganglia; and part of the diencephalon (thalamus and hypothalamus). The major branches of the carotid arteries are the middle cerebral and anterior cerebral arteries. The vertebral arteries join to form the basilar artery, which branches to supply the middle and lower parts of the temporal lobes, occipital lobes, cerebellum, brainstem, and part of the diencephalon. The main branch of the basilar artery is the posterior cerebral artery. The anterior and posterior cerebral circulation is connected at the circle of Willis by the anterior and posterior communicating arteries (Fig. 58-1). (Fig. 56-9 illustrates the arteries at the base of the brain.) Genetic variations in this area are common, and all connecting vessels may not be present. Intracranial pressure (ICP) also influences cerebral blood flow. Increased ICP causes brain compression and reduced cerebral blood flow. One of your major goals when caring for a stroke patient is to reduce secondary injury related to increased ICP (see Chapter 57). Nonmodifiable risk factors include age, gender, ethnicity or race, and family history or heredity. Stroke risk increases with age, doubling each decade after 55 years of age. Two thirds of all strokes occur in individuals older than 65 years, but stroke can occur at any age. Strokes are more common in men, but more women die from stroke than men. Because women tend to live longer than men, they have more opportunity to suffer a stroke.1 Hypertension is the single most important modifiable risk factor, but it is still often undetected and inadequately treated. Increases in systolic and diastolic BP independently increase the risk of stroke. Stroke risk can be reduced by up to 50% with appropriate treatment of hypertension.1–3 Heart disease, including atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy, cardiac valve abnormalities, and cardiac congenital defects, is also a risk factor for stroke. Atrial fibrillation is responsible for about 20% of all strokes.1 The incidence of atrial fibrillation increases with age. Diabetes mellitus is a significant risk factor for stroke. The risk for stroke in people with diabetes mellitus is five times higher than in the general population.1 Increased serum cholesterol and smoking are risk factors for stroke. Smoking nearly doubles the risk of stroke. The risk associated with smoking decreases substantially over time after the smoker quits. After 5 to 10 years of no tobacco use, former smokers have the same risk of stroke as nonsmokers.5 The effect of alcohol on stroke risk appears to depend on the amount consumed. Women who drink more than one alcoholic drink per day and men who drink more than two alcoholic drinks per day are at higher risk for hypertension, which increases their chance of stroke. Illicit drug use, especially cocaine use, has been associated with stroke risk.1 Abdominal obesity increases ischemic stroke risk in all ethnic groups. In addition, obesity is also associated with hypertension, high blood glucose, and elevated blood lipid levels, all of which increase the risk of stroke.1 An association of physical inactivity and increased stroke risk is present in both men and women, regardless of ethnicity. Benefits of physical activity can occur with even light to moderate regular activity and may be related to the beneficial impact of exercise on other risk factors. Nutrition teaching is important for the individual at risk for stroke, since a diet high in fat and low in fruits and vegetables may increase stroke risk. Another risk factor associated with stroke is a past history of a transient ischemic attack (TIA). A TIA is a transient episode of neurologic dysfunction caused by focal brain, spinal cord, or retinal ischemia, but without acute infarction of the brain. Clinical symptoms typically last less than 1 hour. In the past, TIAs were operationally defined as any focal cerebral ischemic event with symptoms lasting less than 24 hours. However, it is important to teach the patient to seek treatment for any stroke symptoms, since there is no way to predict if a TIA will resolve or if it is in fact the development of a stroke.6 In general, one third of individuals who experience a TIA do not experience another event, one third have additional TIAs, and one third progress to stroke.7 TIAs should be treated as medical emergencies. Teach people at risk for TIA to seek medical attention immediately with any stroke-like symptom and to identify the time of symptom onset.8 Unlike a TIA, where ischemia occurs without infarction, a stroke results in infarction and cell death. Strokes are classified as ischemic or hemorrhagic based on the cause and underlying pathophysiologic findings (Fig. 58-2 and Table 58-2). TABLE 58-2 An ischemic stroke results from inadequate blood flow to the brain from partial or complete occlusion of an artery. Nearly 80% of strokes are ischemic.1 A TIA attack is usually a precursor to ischemic stroke. Ischemic strokes are further divided into thrombotic and embolic strokes. A thrombotic stroke occurs from injury to a blood vessel wall and formation of a blood clot (see Fig. 58-2, A). The lumen of the blood vessel becomes narrowed and, if it becomes occluded, infarction occurs. Thrombosis develops readily where atherosclerotic plaques have already narrowed blood vessels. Thrombotic stroke, which is the result of thrombosis or narrowing of the blood vessel, is the most common cause of stroke, accounting for about 60% of strokes.1 Two thirds of thrombotic strokes are associated with hypertension or diabetes mellitus, both of which accelerate atherosclerosis. In 30% to 50% of individuals, thrombotic strokes are preceded by a TIA. Embolic stroke occurs when an embolus lodges in and occludes a cerebral artery, resulting in infarction and edema of the area supplied by the involved vessel (see Fig. 58-2, B). Embolism is the second most common cause of stroke, accounting for about 24% of strokes.1 Most emboli originate in the endocardial (inside) layer of the heart, with plaque breaking off from the endocardium and entering the circulation. The embolus travels upward to the cerebral circulation and lodges where a vessel narrows or bifurcates (splits). Heart conditions associated with emboli include atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, infective endocarditis, rheumatic heart disease, valvular prostheses, and atrial septal defects. Less common causes of emboli include air and fat from long bone (e.g., femur) fractures. Hemorrhagic strokes account for approximately 15% of all strokes and result from bleeding into the brain tissue itself (intracerebral or intraparenchymal hemorrhage) or into the subarachnoid space or ventricles (subarachnoid hemorrhage or intraventricular hemorrhage).1 Intracerebral hemorrhage is bleeding within the brain caused by a rupture of a vessel and accounts for about 10% of all strokes (see Fig. 58-2, C). The prognosis of patients with intracerebral hemorrhage is poor, with the 30-day mortality rate at 40% to 80%. Fifty percent of the deaths occur within the first 48 hours.1 Hypertension is the most common cause of intracerebral hemorrhage (Fig. 58-3). Other causes include vascular malformations, coagulation disorders, anticoagulant and thrombolytic drugs, trauma, brain tumors, and ruptured aneurysms. Hemorrhage commonly occurs during periods of activity. Most often there is a sudden onset of symptoms, with progression over minutes to hours because of ongoing bleeding. Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) occurs when there is intracranial bleeding into the cerebrospinal fluid–filled space between the arachnoid and pia mater membranes on the surface of the brain.9 SAH is commonly caused by rupture of a cerebral aneurysm (congenital or acquired weakness and ballooning of vessels). Aneurysms may be saccular or berry aneurysms, ranging from a few millimeters to 20 to 30 mm in size, or fusiform atherosclerotic aneurysms. The majority of aneurysms are in the circle of Willis. Other causes of SAH include trauma and illicit drug (cocaine) abuse. About 40% of people who have a hemorrhagic stroke due to a ruptured aneurysm die during the first episode. Fifteen percent die from subsequent bleeding.9 The incidence increases with age and is higher in women than men. A stroke can affect many body functions, including motor activity, bladder and bowel elimination, intellectual function, spatial-perceptual alterations, personality, affect, sensation, swallowing, and communication. The functions affected are directly related to the artery involved and area of the brain it supplies (Table 58-3). Manifestations related to right- and left-brain damage differ somewhat and are shown in Fig. 58-4. TABLE 58-3 STROKE MANIFESTATIONS RELATED TO ARTERY INVOLVEMENT The left hemisphere is dominant for language skills in right-handed persons and in most left-handed persons.10 Language disorders involve expression and comprehension of written and spoken words. The patient may experience aphasia, which may be receptive aphasia (loss of comprehension), expressive aphasia (inability to produce language), or global aphasia (total inability to communicate). Aphasia occurs when a stroke damages the dominant hemisphere of the brain. Patterns of aphasia may differ, since the stroke affects different portions of the brain. Aphasia may be classified as nonfluent (minimal speech activity with slow speech that requires obvious effort) or fluent (speech is present but contains little meaningful communication) (Table 58-4). Most types of aphasia are mixed, with impairment in both expression and understanding. A massive stroke may result in global aphasia. Many stroke patients also experience dysarthria, a disturbance in the muscular control of speech. Impairment may involve pronunciation, articulation, and phonation. Dysarthria does not affect the meaning of communication or the comprehension of language, but it does affect the mechanics of speech. Some patients experience a combination of aphasia and dysarthria. TABLE 58-4 Patients who have had a stroke may have difficulty controlling their emotions. Emotional responses may be exaggerated or unpredictable. Depression and feelings associated with changes in body image and loss of function can make this worse.11 Patients may also be frustrated by mobility and communication problems. When manifestations of a stroke occur, diagnostic studies are done to (1) confirm that it is a stroke and not another brain lesion and (2) identify the likely cause of the stroke (Table 58-5). Tests also guide decisions about therapy. TABLE 58-5 *A lumbar puncture to obtain cerebrospinal fluid is avoided if increased intracranial pressure is suspected. Important diagnostic tools for patients who have experienced a stroke are a noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).12 These tests can rapidly distinguish between ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke and help determine the size and location of the stroke. Serial CT scans may be used to assess the effectiveness of treatment and to evaluate recovery. Once the individual suspected of TIA or stroke arrives in the emergency department, it is important to rapidly assess and diagnose the patient (usually through a noncontrast head CT or MRI).12 Rapid access to these diagnostic tools is important, since the results will determine treatment options for the patient. If the suspected cause of the stroke includes emboli from the heart, diagnostic cardiac tests should be done. Blood tests are also done to help identify conditions contributing to stroke and to guide treatment (see Table 58-5). The LICOX system may be used as a diagnostic tool to evaluate the progression of stroke. LICOX measures brain oxygenation and temperature (see discussion in Chapter 57 on p. 1365 and Fig. 57-10). Secondary brain injury adds significantly to mortality risk and poor functional outcome after a stroke. Primary prevention is a priority for decreasing morbidity and mortality risk from stroke (Table 58-6). The goals of stroke prevention include health promotion for a healthy lifestyle and management of modifiable risk factors to prevent a stroke. Health promotion focuses on (1) healthy diet, (2) weight control, (3) regular exercise, (4) no smoking, (5) limitation on alcohol consumption, and (6) routine health assessments. Patients with known risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, high serum lipids, or cardiac dysfunction require close management. TABLE 58-6 Measures to prevent the development of a thrombus or an embolus are used in patients with TIAs, since they are at high risk for stroke. Antiplatelet drugs are usually the chosen treatment to prevent stroke in patients who have had a TIA. Aspirin is the most frequently used antiplatelet agent, commonly at a dose of 81 to 325 mg/day. Other drugs include ticlopidine (Ticlid), clopidogrel (Plavix), dipyridamole (Persantine), and combined dipyridamole and aspirin (Aggrenox).13 For patients who have atrial fibrillation, oral anticoagulation can include warfarin (Coumadin), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), and dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa). The primary advantage of rivaroxaban and dabigatran over warfarin is that these drugs do not need close monitoring or dosage adjustments. Statins (simvastatin [Zocor], lovastatin [Mevacor]) have also been shown to be effective in the prevention of stroke for individuals who have experienced a TIA in the past.14

Nursing Management

Stroke

Warning Signs of Stroke

Include the following information in the teaching plan for a patient at risk for stroke and the patient’s caregiver.

Pathophysiology of Stroke

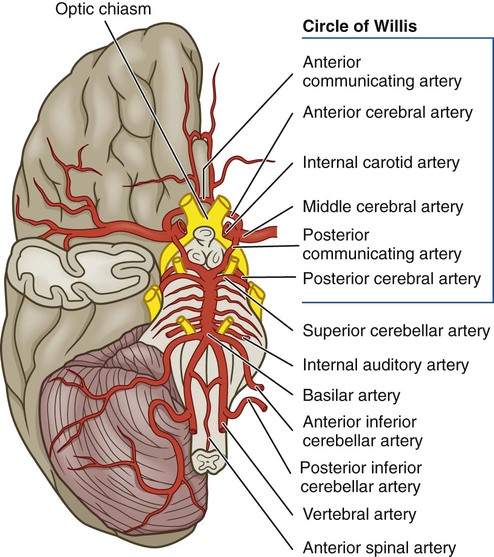

Anatomy of Cerebral Circulation

Regulation of Cerebral Blood Flow

Risk Factors for Stroke

Nonmodifiable Risk Factors

Modifiable Risk Factors

Transient Ischemic Attack

Types of Stroke

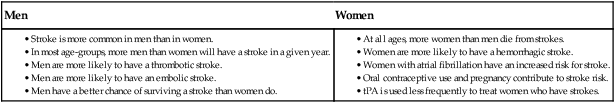

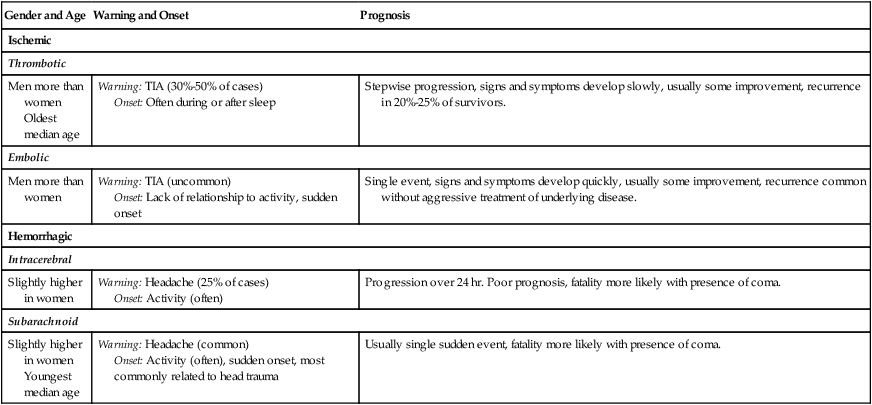

Gender and Age

Warning and Onset

Prognosis

Ischemic

Thrombotic

Men more than women

Oldest median age

Warning: TIA (30%-50% of cases)

Onset: Often during or after sleep

Stepwise progression, signs and symptoms develop slowly, usually some improvement, recurrence in 20%-25% of survivors.

Embolic

Men more than women

Warning: TIA (uncommon)

Onset: Lack of relationship to activity, sudden onset

Single event, signs and symptoms develop quickly, usually some improvement, recurrence common without aggressive treatment of underlying disease.

Hemorrhagic

Intracerebral

Slightly higher in women

Warning: Headache (25% of cases)

Onset: Activity (often)

Progression over 24 hr. Poor prognosis, fatality more likely with presence of coma.

Subarachnoid

Slightly higher in women

Youngest median age

Warning: Headache (common)

Onset: Activity (often), sudden onset, most commonly related to head trauma

Usually single sudden event, fatality more likely with presence of coma.

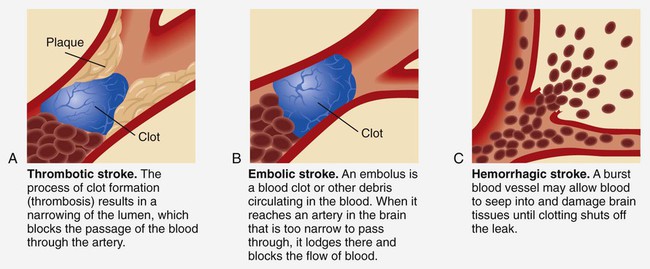

Ischemic Stroke

Thrombotic Stroke.

Embolic Stroke.

Hemorrhagic Stroke

Intracerebral Hemorrhage.

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage.

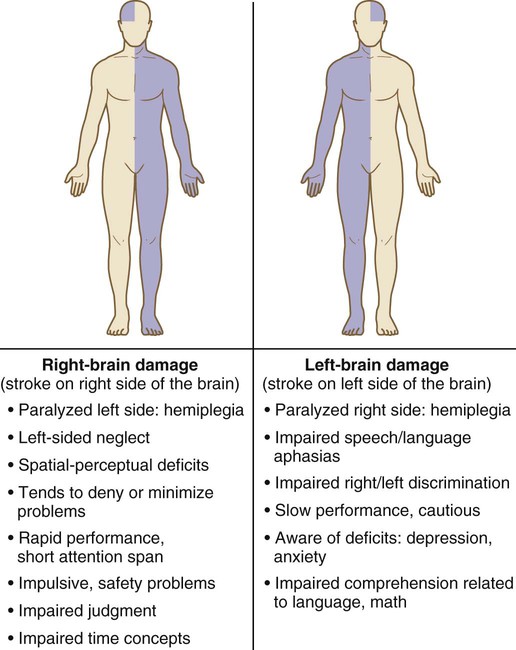

Clinical Manifestations of Stroke

Artery

Deficit

Anterior cerebral

Motor and/or sensory deficit (contralateral), sucking or rooting reflex, rigidity, gait problems, loss of proprioception and fine touch

Middle cerebral

Dominant side: Aphasia, motor and sensory deficit, hemianopsia

Nondominant side: Neglect, motor and sensory deficit, hemianopsia

Posterior cerebral

Hemianopsia, visual hallucination, spontaneous pain, motor deficit

Vertebral

Cranial nerve deficits, diplopia, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, dysarthria, dysphagia, and/or coma

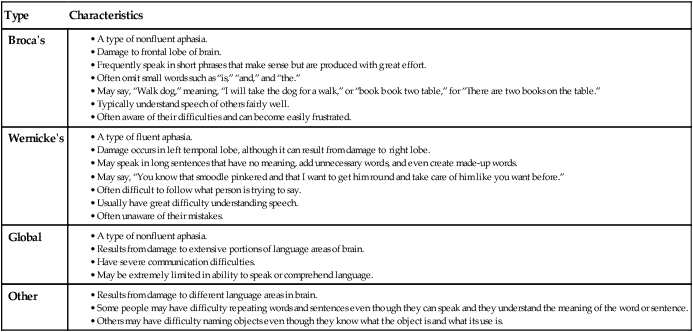

Communication

Affect

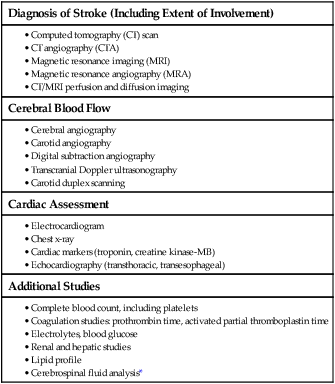

Diagnostic Studies for Stroke

Diagnosis of Stroke (Including Extent of Involvement)

Cerebral Blood Flow

Cardiac Assessment

Additional Studies

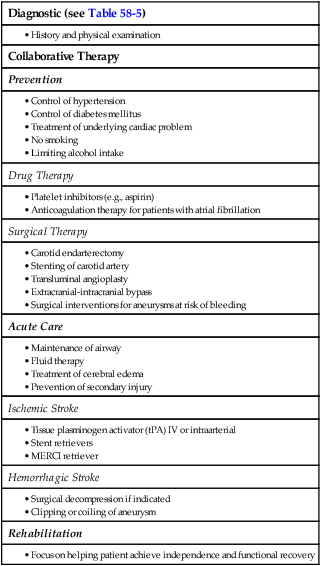

Collaborative Care for Stroke

Preventive Therapy

Diagnostic (see Table 58-5)

Collaborative Therapy

Prevention

Drug Therapy

Surgical Therapy

Acute Care

Ischemic Stroke

Hemorrhagic Stroke

Rehabilitation

Preventive Drug Therapy.