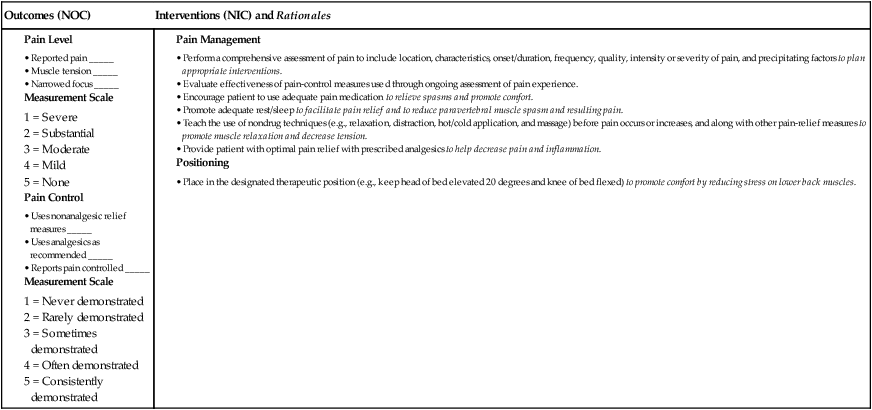

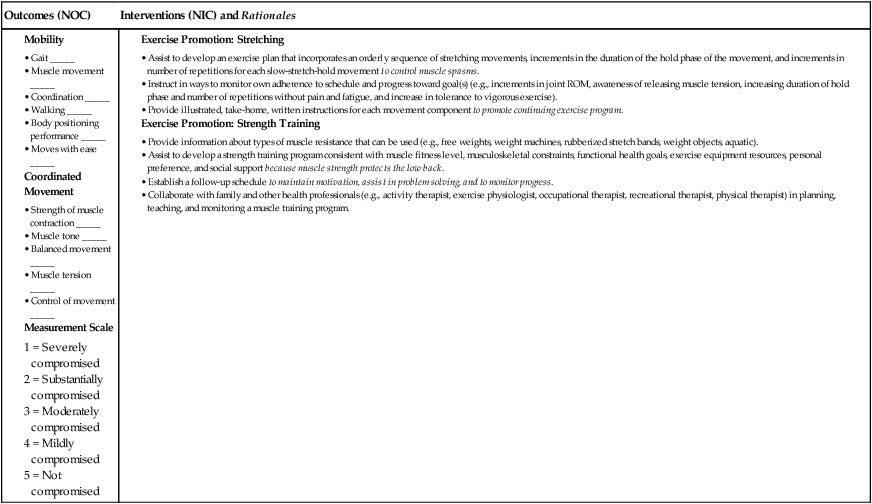

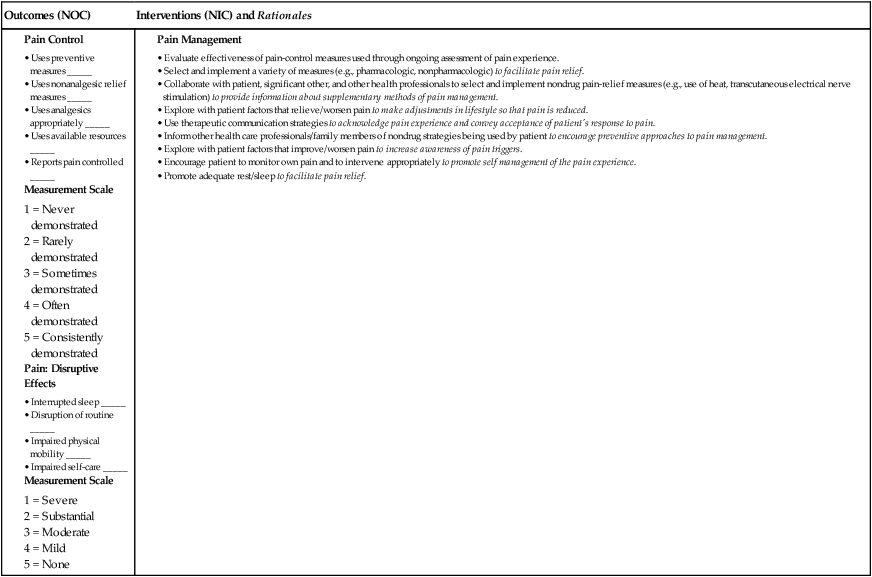

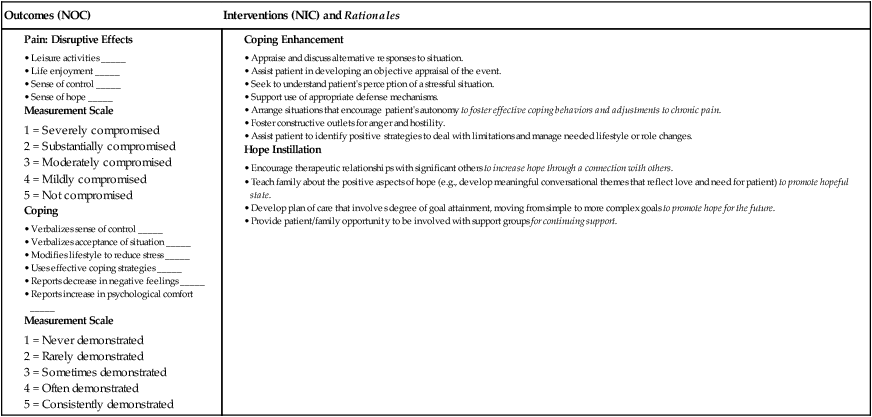

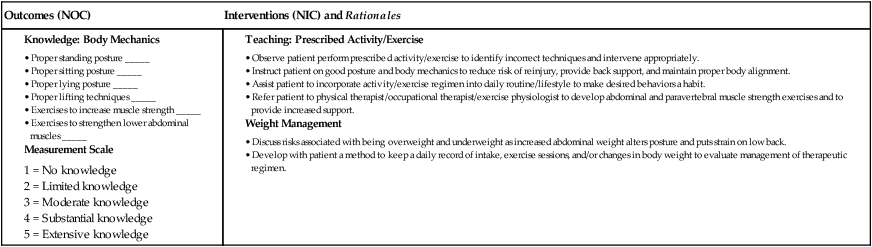

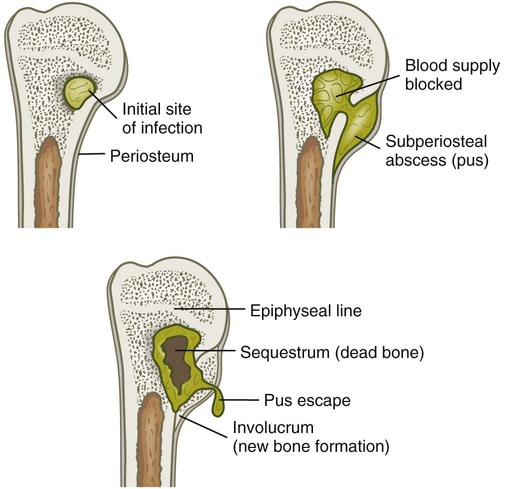

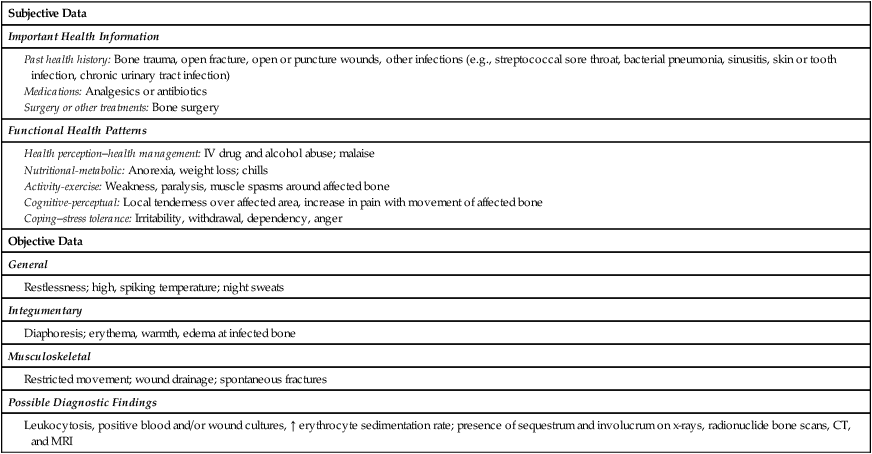

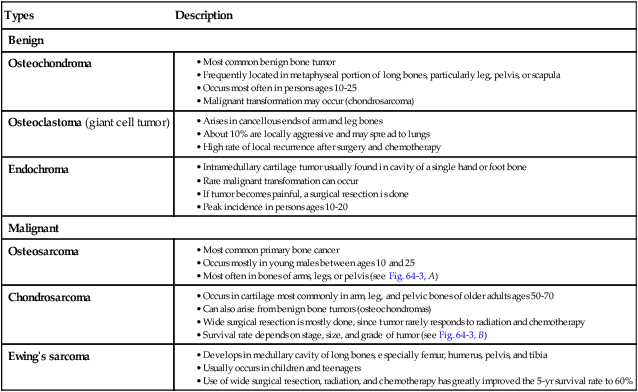

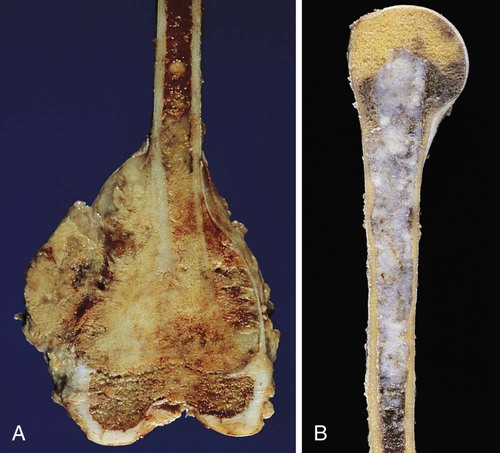

Chapter 64 1. Describe the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, collaborative care, and nursing management of osteomyelitis. 2. Differentiate among the types, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and collaborative care of bone cancer. 3. Differentiate between the causes and characteristics of acute and chronic low back pain. 4. Explain the conservative and surgical therapy of intervertebral disc damage. 5. Describe the postoperative nursing management of a patient who has undergone vertebral disc surgery. 6. Specify the etiology and nursing management of common foot disorders. 7. Describe the etiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and collaborative and nursing management of osteomalacia, osteoporosis, and Paget’s disease. Osteomyelitis is a severe infection of the bone, bone marrow, and surrounding soft tissue. Although Staphylococcus aureus is a common cause of infection, a variety of microorganisms may cause osteomyelitis1 (Table 64-1). TABLE 64-1 ORGANISMS CAUSING OSTEOMYELITIS Once ischemia occurs, the bone dies. The area of devitalized bone eventually separates from the surrounding living bone, forming sequestra. The part of the periosteum that continues to have a blood supply forms new bone called involucrum (Fig. 64-1). It is difficult for blood-borne antibiotics or white blood cells (WBCs) to reach the sequestrum. A sequestrum may become a reservoir for microorganisms that spread to other sites, including the lungs and brain. If the sequestrum does not resolve on its own or is debrided surgically, a sinus tract may develop, resulting in chronic, purulent cutaneous drainage. Chronic osteomyelitis refers to a bone infection that persists for longer than 1 month or an infection that has failed to respond to the initial course of antibiotic therapy. Chronic osteomyelitis is either a continuous, persistent problem (a result of inadequate acute treatment) or a process of exacerbations and remissions (Fig. 64-2). Systemic signs may be diminished, with local signs of infection more common, including constant bone pain and swelling and warmth at the infection site. Over time, granulation tissue turns to scar tissue. This avascular scar tissue provides an ideal site for continued microorganism growth that cannot be penetrated by antibiotics. A bone or soft tissue biopsy is the definitive way to determine the causative microorganism. The patient’s blood and wound cultures are frequently positive for microorganisms.2 An elevated WBC count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) may also be found. X-ray signs suggestive of osteomyelitis usually do not appear until 10 days to weeks after the initial clinical symptoms, by which time the disease will have progressed. Radionuclide bone scans (gallium and indium) are helpful in diagnosis and are usually positive in the area of infection. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans may be used to help identify the extent of the infection.3 Treatment of chronic osteomyelitis includes surgical removal of the poorly vascularized tissue and dead bone and the extended use of antibiotics.5 Antibiotic-impregnated polymethyl methacrylate bead chains may also be implanted at this time to help combat the infection. After debridement of the devitalized and infected tissue, the wound may be closed and a suction irrigation system inserted. Intermittent or constant irrigation of the affected bone with antibiotics may also be initiated. Protection of the limb or the surgical site with casts or braces is often done. Negative-pressure wound therapy (vacuum-assisted wound closure) may be used (see pp. 181–182 in Chapter 12). Hyperbaric oxygen with 100% oxygen may be given as an adjunct therapy in refractory cases of chronic osteomyelitis. This therapy is thought to stimulate circulation and healing in the infected tissue (see pp. 182–183 in Chapter 12). Orthopedic prosthetic devices, if a source of chronic infection, must be removed. Muscle flaps or skin grafting provides wound coverage over the dead space (cavity) in the bone. Bone grafts may help to restore blood flow. Amputation of the extremity may be indicated when bone destruction is extensive and to save the patient’s life or to improve quality of life. Subjective and objective data that should be obtained from an individual with osteomyelitis are presented in Table 64-2. TABLE 64-2 NURSING ASSESSMENT Health perception–health management: IV drug and alcohol abuse; malaise Nutritional-metabolic: Anorexia, weight loss; chills Activity-exercise: Weakness, paralysis, muscle spasms around affected bone Cognitive-perceptual: Local tenderness over affected area, increase in pain with movement of affected bone Coping–stress tolerance: Irritability, withdrawal, dependency, anger • Acute pain related to inflammatory process secondary to infection • Ineffective self–health management related to lack of knowledge regarding long-term management of osteomyelitis • Impaired physical mobility related to pain, immobilization devices, and weight-bearing limitations Some immobilization of the affected limb (e.g., splint, traction) is usually indicated to decrease pain. Carefully handle the involved limb and avoid excessive manipulation, which increases pain and may cause a pathologic fracture. Assess the patient’s pain. Minor to severe pain may be experienced with muscle spasms. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioid analgesics, and muscle relaxants may be prescribed to provide patient comfort. Encourage nondrug approaches to pain management (e.g., guided imagery, relaxation breathing) (see Chapters 7 and 9). Benign bone tumors are more common than primary malignant tumors. The main types of benign bone tumors are osteochondroma, osteoclastoma, and endochroma (Table 64-3). These types of tumors are often removed by surgery. TABLE 64-3 • Occurs in cartilage most commonly in arm, leg, and pelvic bones of older adults ages 50-70 • Can also arise from benign bone tumors (osteochondromas) • Wide surgical resection is mostly done, since tumor rarely responds to radiation and chemotherapy • Survival rate depends on stage, size, and grade of tumor (see Fig. 64-3, B) A sarcoma is a malignant tumor that can develop in bone, muscle, fat, nerve, or cartilage. The most common types of malignant bone tumors are osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and Ewing’s sarcoma (see Table 64-3). Annually about 2900 new cases of bone (and joint) cancer occur in the United States, with an estimated 1400 deaths.6 Primary malignant tumors occur most often during childhood and young adulthood. They are characterized by their rapid metastasis and bone destruction. Osteosarcoma is a primary malignant bone tumor that is extremely aggressive and rapidly metastasizes to distant sites. It usually occurs in the metaphyseal region of the long bones of extremities, particularly in the regions of the distal femur, proximal tibia, and proximal humerus, as well as the pelvis (Fig. 64-3, A). Osteosarcoma is the most common malignant bone tumor affecting children and young adults. It can also occur, but not as commonly, in older adults. It is most often associated with Paget’s disease and prior radiation. The use of adjunct chemotherapy after amputation or limb salvage has increased the 5-year survival rate to 70% in people without metastasis. Chemotherapy includes methotrexate, doxorubicin (Adriamycin), cisplatin (Platinol), cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan), etoposide (VePesid), bleomycin (Blenoxane), dactinomycin (Cosmegen), and ifosfamide (Ifex).7

Nursing Management

Musculoskeletal Problems

Osteomyelitis

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Organism

Predisposing Problem

Staphylococcus aureus

Pressure ulcer, penetrating wound, open fracture, orthopedic surgery, vascular insufficiency disorders (e.g., diabetes, atherosclerosis)

Staphylococcus epidermidis

Indwelling prosthetic devices (e.g., joint replacements, fracture fixation devices)

Streptococcus viridans

Abscessed tooth, gingival disease

Escherichia coli

Urinary tract infection

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Tuberculosis

Neisseria gonorrhoeae

Gonorrhea

Pseudomonas

Puncture wounds, IV drug use

Salmonella

Sickle cell disease

Fungi, mycobacteria

Immunocompromised host

Clinical Manifestations and Complications

Diagnostic Studies

Collaborative Care

Nursing Management Osteomyelitis

Nursing Assessment

Osteomyelitis

Subjective Data

Important Health Information

Functional Health Patterns

Objective Data

General

Integumentary

Musculoskeletal

Possible Diagnostic Findings

Nursing Diagnoses

Nursing Implementation

Health Promotion.

Acute Intervention.

Bone Tumors

Benign Bone Tumors

Types

Description

Benign

Osteochondroma

Osteoclastoma (giant cell tumor)

Endochroma

Malignant

Osteosarcoma

Chondrosarcoma

Ewing’s sarcoma

Malignant Bone Tumors

Osteosarcoma

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nursing Management: Musculoskeletal Problems

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access