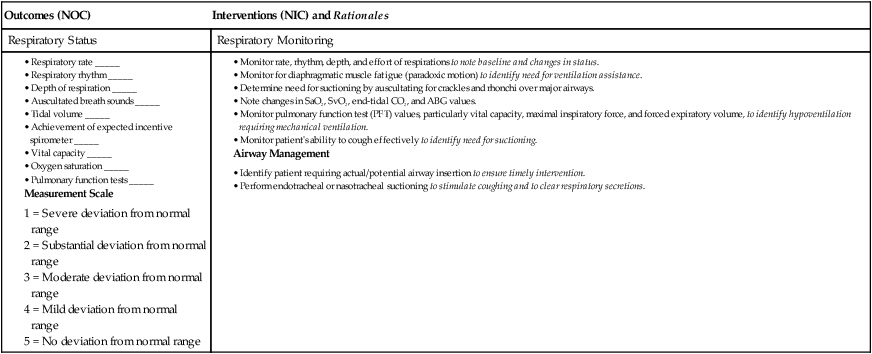

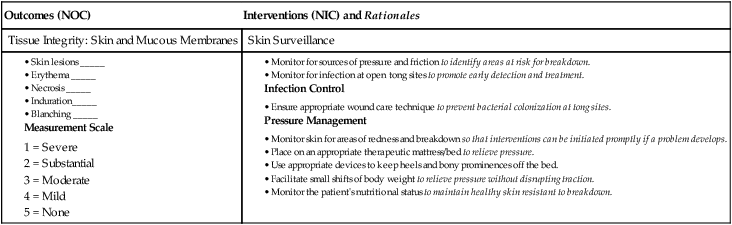

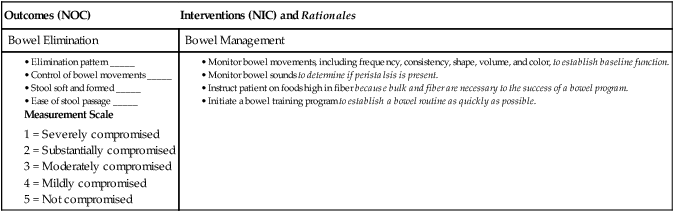

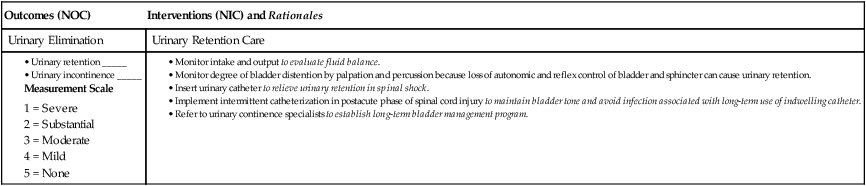

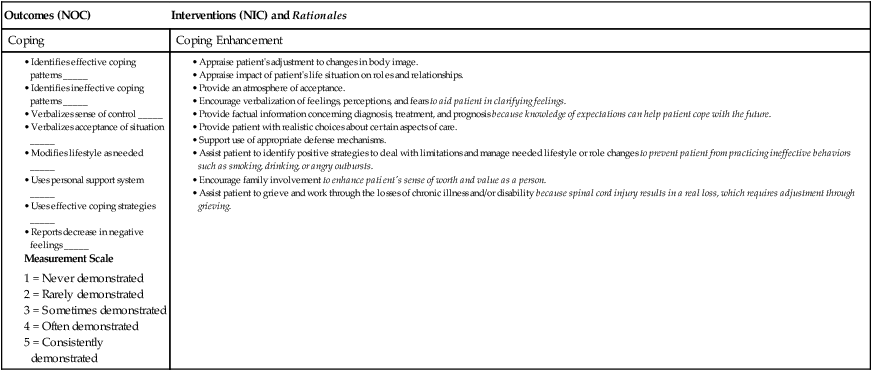

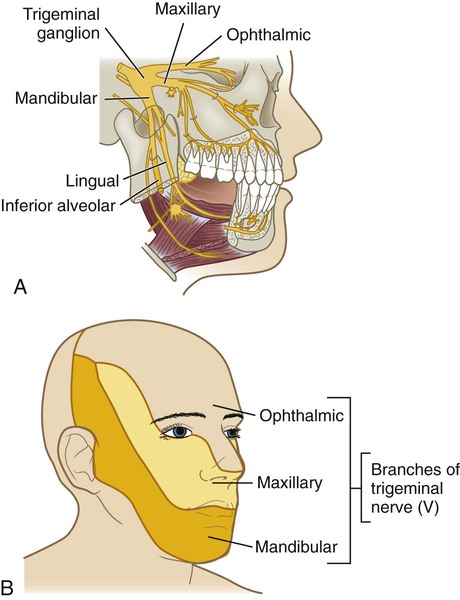

1. Explain the etiology, clinical manifestations, collaborative care, and nursing management of trigeminal neuralgia and Bell’s palsy. 2. Explain the etiology, clinical manifestations, collaborative care, and nursing management of Guillain-Barré syndrome, botulism, tetanus, and neurosyphilis. 3. Describe the classification of spinal cord injuries and associated clinical manifestations. 4. Describe the clinical manifestations, collaborative care, and nursing management of neurogenic and spinal shock. 5. Relate the clinical manifestations of spinal cord injury to the level of disruption and rehabilitation potential. 6. Describe the nursing management of the major physical and psychologic problems of the patient with a spinal cord injury. 7. Describe the effects of spinal cord injury on the older adult. 8. Explain the types, clinical manifestations, collaborative care, and nursing management of spinal cord tumors. eTABLE 61-1 COMPARISON OF MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS AND GUILLAIN-BARRÉ SYNDROME CNS, Central nervous system; PNS, peripheral nervous system; URI, upper respiratory tract infection. Trigeminal neuralgia (tic douloureux) is sudden, usually unilateral, severe, brief, stabbing, recurrent episodes of pain in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve. It is diagnosed in approximately 150,000 Americans each year and is the most commonly diagnosed neuralgic condition. It is seen approximately twice as often in women as in men. The majority of cases (more than 90%) are diagnosed in individuals over age 40.1 The trigeminal nerve is the fifth cranial nerve (CN V) and has both motor and sensory branches. In trigeminal neuralgia the sensory or afferent branches, primarily the maxillary and mandibular branches, are involved (Fig. 61-1). The etiology and pathophysiology of trigeminal neuralgia is not fully understood.2 One theory is that blood vessels, especially the superior cerebellar artery, become compressed, resulting in chronic irritation of the trigeminal nerve at the root entry zone. This irritation leads to increased firing of the afferent or sensory fibers. Risk factors are multiple sclerosis and hypertension. Other factors that may cause neuralgia include herpesvirus infection, infection of the teeth and jaw, and a brainstem infarct. Once the diagnosis is made, the goal of treatment is relief of pain either medically or surgically (Tables 61-1 and 61-2). TABLE 61-2 SURGICAL THERAPY FOR TRIGEMINAL NEURALGIA Antiseizure drug therapy may reduce pain by stabilizing the neuronal membrane and blocking nerve firing.2 These first-line drugs include carbamazepine (Tegretol), oxcarbazepine (Trileptal), topiramate (Topamax), clonazepam (Klonopin), phenytoin (Dilantin), lamotrigine (Lamictal), and divalproex (Depakote). Gabapentin (Neurontin) or baclofen (Lioresal) can be used in combination with any of the antiseizure drugs if a single agent is not effective. Tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline (Elavil) or nortriptyline (Pamelor, Aventyl) can be used to treat constant burning, or aching pain.2 Analgesics or opioids are usually not effective in controlling pain. If a conservative approach including drug therapy is not effective, surgical therapy is available (see Table 61-2). Glycerol rhizotomy is a percutaneous procedure that consists of an injection of glycerol through the foramen ovale into the trigeminal cistern (Fig. 61-2). Percutaneous radiofrequency rhizotomy is an outpatient procedure consisting of placing a needle into the trigeminal rootlets that are adjacent to the pons and destroying the area by means of a radiofrequency current. This can result in facial numbness (although some degree of sensation may be retained), corneal anesthesia, and trigeminal motor weakness.3 Microvascular decompression of the trigeminal nerve is another commonly used procedure for neuralgia. It is done by first performing a small craniotomy behind the ear (suboccipital craniotomy). The next step involves displacing and repositioning the blood vessels that appear to be compressing the nerve at the root entry zone where it exits the pons. This procedure relieves pain without residual sensory loss, but it is potentially dangerous.3 Gamma knife radiosurgery is another surgical treatment that is used to treat trigeminal neuralgia. Radiosurgery (see Chapter 57) using a gamma knife provides precise radiation of the proximal trigeminal nerve identified on high-resolution imaging. Appropriate teaching related to surgical procedures depends on the type of procedure planned (e.g., percutaneous). Patients need to know that they will be awake during local procedures so that they can cooperate when corneal and ciliary reflexes and facial sensations are checked. After the procedure the patient’s pain is compared with the preoperative level. The corneal reflex, extraocular muscles, hearing, sensation, and facial nerve function are evaluated frequently (see Chapter 56). If the corneal reflex is impaired, take special care to protect the eyes. This includes the use of artificial tears or eye shields. If intracranial surgery is performed, general postoperative nursing care after a craniotomy is appropriate. (Nursing care related to craniotomy is discussed in Chapter 57 on p. 1379.) Bell’s palsy (peripheral facial paralysis, acute benign cranial polyneuritis) is a disorder characterized by inflammation of the facial nerve (CN VII) on one side of the face in the absence of any other disease such as a stroke. Bell’s palsy is an acute, peripheral facial paresis of unknown cause. Each year approximately 40,000 Americans are diagnosed with Bell’s palsy. It can affect any age-group. Despite its good prognosis, Bell’s palsy leaves more than 8000 people a year in the United States with permanent, potentially disfiguring facial weakness.4 Although the exact etiology is not known, it is believed that a viral infection such as viral meningitis or activation of herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV1) may trigger Bell’s palsy. The viral infection causes inflammation, edema, ischemia, and eventual demyelination of the nerve, creating pain and alterations in motor and sensory function. Bell’s palsy has also been associated with influenza or a flu-like illness, headaches, chronic middle ear infection, hypertension, diabetes, sarcoidosis, tumors, Lyme disease, and trauma such as skull fracture or facial injury.4 Bell’s palsy is considered benign, with full recovery in 3 to 6 months, especially if treatment is begun immediately. A small group of patients have long-term facial paralysis.4 The onset of Bell’s palsy is often accompanied by an outbreak of herpes vesicles in or around the ear. Patients may complain of pain around and behind the ear. Additional manifestations may include fever, tinnitus, and hearing deficit. Paralysis of the motor branches of the facial nerve typically results in flaccidity of the affected side of the face, with drooping of the mouth accompanied by drooling (Fig. 61-3). Guillain-Barré syndrome (Landry-Guillain-Barré-Strohl syndrome, postinfectious polyneuropathy, ascending polyneuropathic paralysis) is an acute, rapidly progressing, and potentially fatal form of polyneuritis. It is characterized by ascending, symmetric paralysis that usually affects cranial nerves and the peripheral nervous system. The syndrome is rare, affecting an estimated 3000 to 6000 Americans each year. It affects males and females equally.5,6 The etiology of this disorder is unknown. Both cellular and humoral immune mechanisms play a role in the immune reaction directed at the nerves. The result is a loss of myelin (a segmental demyelination) and edema and inflammation of the affected nerves. As demyelination occurs, the transmission of nerve impulses is stopped or slowed down. The muscles innervated by the damaged peripheral nerves undergo denervation and atrophy. In the recovery phase, remyelination occurs slowly, and neurologic function returns in a proximal-to-distal pattern.6 Guillain-Barré syndrome is similar in presentation to multiple sclerosis (MS), and therefore a full diagnostic workup should be performed to rule out MS (see Chapter 59). The syndrome is often preceded by immune system stimulation from a viral infection, trauma, surgery, or viral immunizations. Campylobacter jejuni gastroenteritis is thought to precede Guillain-Barré syndrome in approximately 30% of cases.5–7 Guillain-Barré syndrome is a heterogeneous condition with manifestations ranging from mild to severe. Weakness of the lower extremities (evolving more or less symmetrically) occurs over hours to days to weeks, usually peaking about the fourteenth day. Paresthesia (numbness and tingling) is common, with paralysis usually following in the extremities. Hypotonia (reduced muscle tone) and areflexia (lack of reflexes) are common manifestations.5–7 In Guillain-Barré syndrome, autonomic nervous system dysfunction results, with manifestations of orthostatic hypotension, hypertension, and abnormal vagal responses (bradycardia, heart block, asystole). Other autonomic dysfunctions include bowel and bladder dysfunction, facial flushing, and diaphoresis. Patients may also have syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) secretion.8 (SIADH is discussed in Chapter 50.) Cranial nerve involvement is manifested as facial weakness, extraocular eye movement difficulties, dysphagia, and paresthesia of the face. Management of Guillain-Barré syndrome is aimed at supportive care, particularly ventilatory support, during the acute phase. Plasmapheresis is used in the first 2 weeks. (Plasmapheresis is discussed in Chapter 14.) IV administration of high-dose immunoglobulin (Sandoglobulin) has been as effective as plasma exchange and is more readily available. The objective of therapy is to support body systems until the patient recovers. Respiratory failure and infection are serious threats. Monitoring the vital capacity and ABGs is essential. If the vital capacity drops to less than 800 mL or the ABGs deteriorate, endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy may be done so that the patient can be mechanically ventilated (see Chapter 68). If fever develops, obtain sputum cultures to identify the pathogen. Appropriate antibiotic therapy is then initiated. Nutritional needs must be met in spite of possible problems associated with delayed gastric emptying, paralytic ileus, and potential for aspiration if the gag reflex is lost. In addition to testing for the gag reflex, note drooling and other difficulties with secretions that may indicate an inadequate gag reflex. Initially, enteral or parenteral nutrition may be used to ensure adequate caloric intake. Because of delayed gastric emptying, assess residual volumes of the feedings at regular intervals or before feedings (see Chapter 40). Throughout the course of the illness, provide support and encouragement to the patient, caregiver, and family. Although 85% to 95% of patients almost completely recover, it is generally a slow process that takes months or years. About 30% of those with Guillain-Barré have some residual weakness.5–7 Botulism is rare but the most serious type of food poisoning. It is caused by gastrointestinal (GI) absorption of the neurotoxin produced by Clostridium botulinum. This organism is found in the soil, and the spores are difficult to destroy. It can grow in any food contaminated with the spores. Improper home canning of foods is often the cause.9 It is thought that the neurotoxin destroys or inhibits the neurotransmission of acetylcholine at the myoneural junction, resulting in disturbed muscle innervation. The clinical manifestations, prevention, and treatment are presented in Table 42-24. Patient and caregiving teaching related to food poisoning are presented in Table 42-25. Nursing care during the acute illness is similar to that for Guillain-Barré syndrome. Supportive nursing interventions include rest, activities to maintain respiratory function, adequate nutrition, and prevention of loss of muscle mass. Tetanus (lockjaw) is a severe infection of the nervous system affecting spinal and cranial nerves. It results from the effects of a potent neurotoxin released by the anaerobic bacillus Clostridium tetani. The spores of the bacillus are present in soil, garden mold, and manure. C. tetani enters the body through a wound that provides an appropriate low-oxygen environment for the organisms to mature and produce toxin. Examples of possible wounds include IV drug use injection sites, human and animal bites, burns, frostbite, open fractures, and gunshot wounds.10,11 Initial manifestations of tetanus include stiffness in the jaw (trismus) and neck and signs of infection (e.g., fever). As the disease progresses, the neck muscles, back, abdomen, and extremities become progressively rigid. In severe forms, continuous tonic seizures may occur with opisthotonos (extreme arching of the back and retraction of the head). Laryngeal and respiratory spasms cause apnea and anoxia. The slightest noise, jarring motion, or bright light can set off a seizure. These seizures are agonizingly painful. Mortality rate is almost 100% in the severe form.11 Tetanus prevention and immunizations, which are the most important factors influencing the incidence of this disease, are summarized in Table 69-6. Adults should receive a tetanus and diphtheria toxoid booster every 10 years. Teach the patient that immediate, thorough cleansing of all wounds with soap and water is important to prevent tetanus. If an open wound occurs and the patient has not been immunized within 5 years, the health care provider should be contacted so that a tetanus booster can be given. The management of tetanus includes administration of a tetanus toxoid, diphtheria toxoid, and pertussis (Tdap) booster and tetanus immune globulin (TIG) in different sites before the onset of symptoms to neutralize circulating toxins (see Table 69-6). A much larger dose of TIG is administered to patients with clinical manifestations of tetanus.10–12 Control of spasms is essential and is managed by sedation and skeletal muscle relaxation, usually with diazepam (Valium), barbiturates, and, in severe cases, neuromuscular blocking agents such as vecuronium (Norcuron) that act to paralyze skeletal muscles. Opioid analgesics such as morphine or fentanyl are also indicated for pain management. A 10- to 14-day course of penicillin, metronidazole, tetracycline, or doxycycline is recommended to inhibit further growth of C. tetani.11 Neurosyphilis is caused by Treponema pallidum, the bacteria that cause syphilis. It usually occurs about 10 to 20 years after a person is first infected with syphilis. Not everyone who has syphilis will develop this complication. It is the result of untreated or inadequately treated syphilis (see Chapter 53). The organism can invade the central nervous system within a few months of the original infection. Untreated neurosyphilis, although not contagious, can be fatal. Late neurosyphilis results from degenerative changes in the spinal cord (tabes dorsalis) and brainstem (general paresis). Tabes dorsalis (progressive locomotor ataxia) is characterized by vague, sharp pains in the legs; ataxia; “slapping” gait; loss of proprioception and deep tendon reflexes; and zones of hyperesthesia. Charcot’s joints, which are characterized by enlargement, bone destruction, and hypermobility, also occur as a result of joint effusion and edema. Other manifestations of neurosyphilis include seizures, vision and hearing problems, and cognitive impairment.13 Management includes treatment with penicillin, symptomatic care, and protection from physical injury.13 The prognosis after treatment depends on how severe the neurosyphilis is before treatment. The neurologic deficits may remain or progress after treatment. Spinal cord injury (SCI) is caused by trauma or damage to the spinal cord. It can result in either a temporary or permanent alteration in the function of the spinal cord. About 12,000 Americans suffer SCIs each year. About 260,000 persons in the United States are living with SCI.14,15 With improved treatment strategies, even the very young patient with an SCI can anticipate a long life. The potential for disruption of individual growth and development, altered family dynamics, economic loss in terms of employment, and the high cost of rehabilitation and long-term health care make SCI a major problem. Young adult men between ages 16 and 30 years have the greatest risk for SCI. Eighty-one percent of people with SCI are male. There has also been an increase in the number of older adults with SCIs. This trend toward older age at time of injury is reflected in the overall increase in mean age of people with SCI from 28 years in the 1970s to 40 years at this time.15 SCIs are usually a result of trauma. The most common causes are motor vehicle collisions (42%), falls (27%), violence (15%), sports injuries (7%), and other miscellaneous causes (8%).15

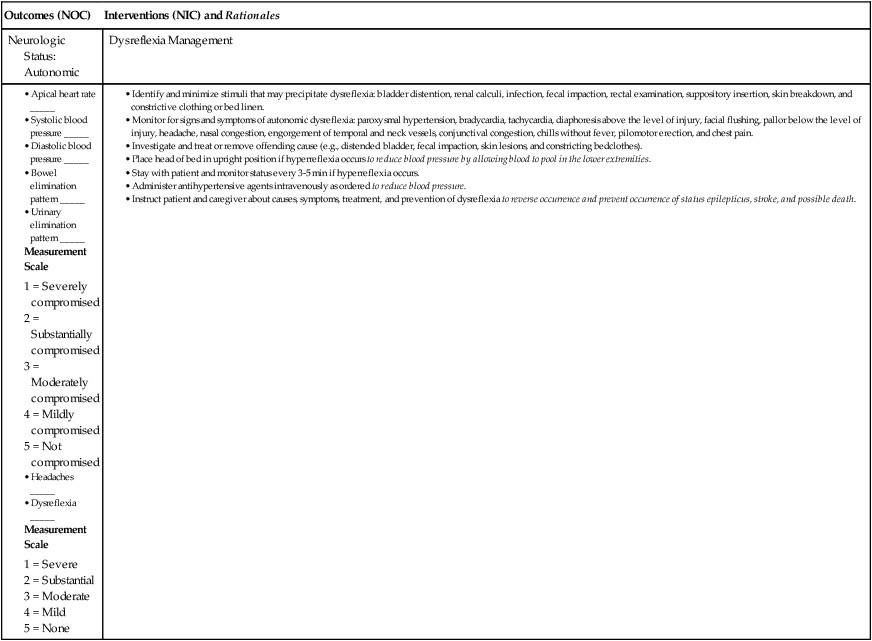

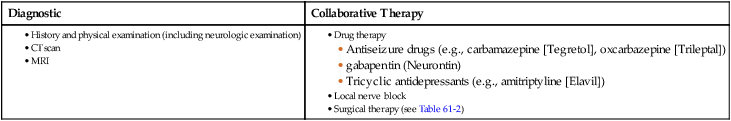

Nursing Management

Peripheral Nerve and Spinal Cord Problems

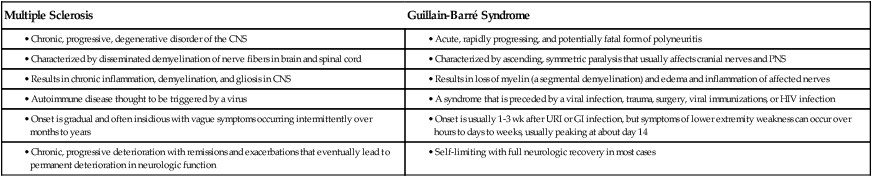

Multiple Sclerosis

Guillain-Barré Syndrome

Cranial Nerve Disorders

Trigeminal Neuralgia

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Collaborative Care

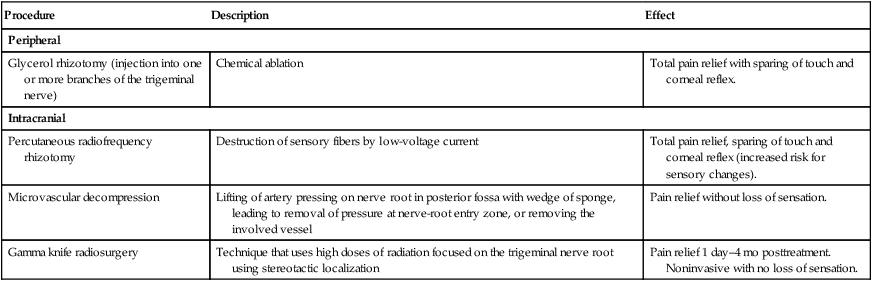

Procedure

Description

Effect

Peripheral

Glycerol rhizotomy (injection into one or more branches of the trigeminal nerve)

Chemical ablation

Total pain relief with sparing of touch and corneal reflex.

Intracranial

Percutaneous radiofrequency rhizotomy

Destruction of sensory fibers by low-voltage current

Total pain relief, sparing of touch and corneal reflex (increased risk for sensory changes).

Microvascular decompression

Lifting of artery pressing on nerve root in posterior fossa with wedge of sponge, leading to removal of pressure at nerve-root entry zone, or removing the involved vessel

Pain relief without loss of sensation.

Gamma knife radiosurgery

Technique that uses high doses of radiation focused on the trigeminal nerve root using stereotactic localization

Pain relief 1 day–4 mo posttreatment. Noninvasive with no loss of sensation.

Drug Therapy.

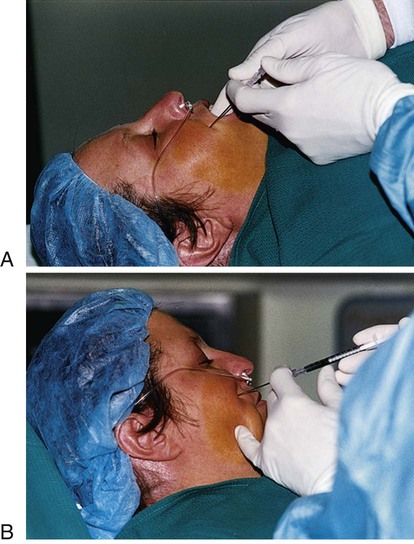

Surgical Therapy.

Nursing Management Trigeminal Neuralgia

Bell’s Palsy

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnostic Studies

Polyneuropathies

Guillain-Barré Syndrome

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Clinical Manifestations and Complications

Nursing and Collaborative Management Guillain-Barré Syndrome

Botulism

Tetanus

Neurosyphilis

Spinal Cord Problems

Spinal Cord Injury

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Nursing Management: Peripheral Nerve and Spinal Cord Problems

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access