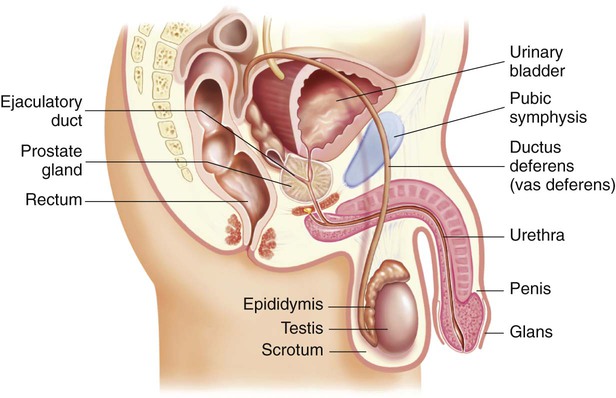

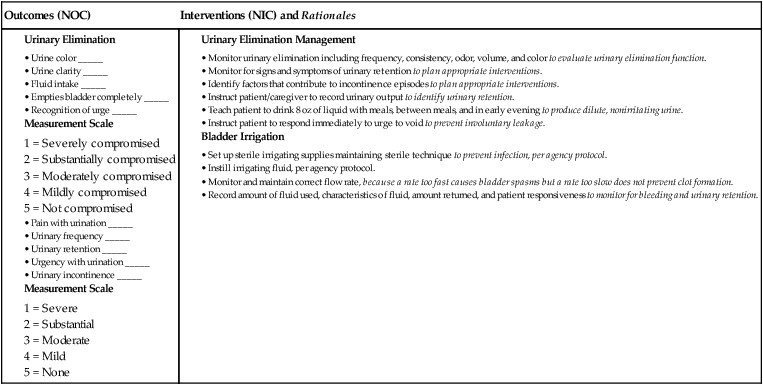

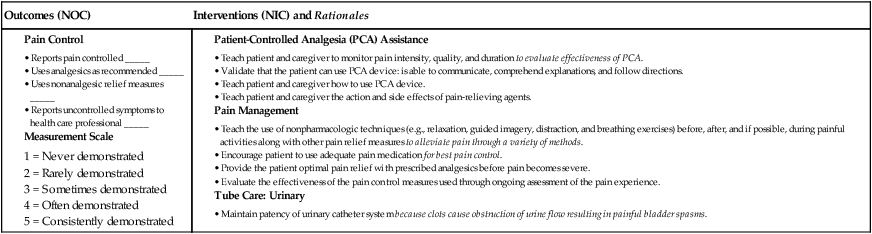

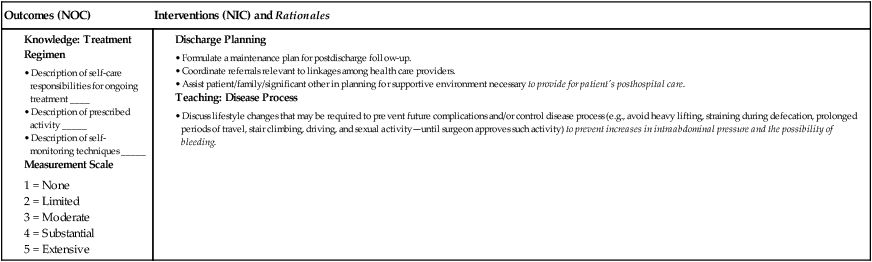

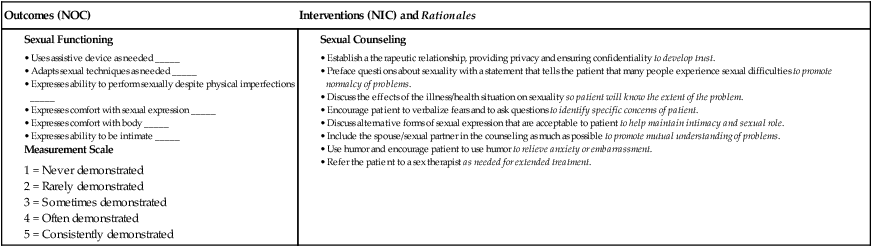

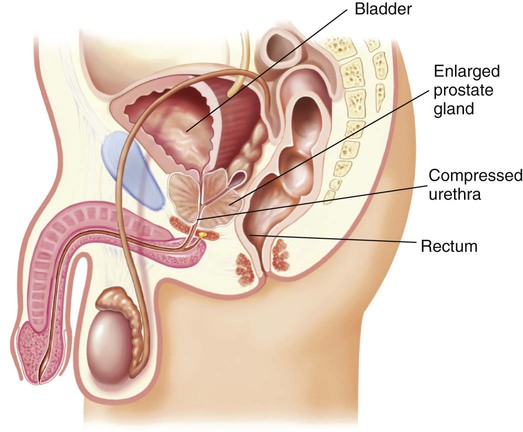

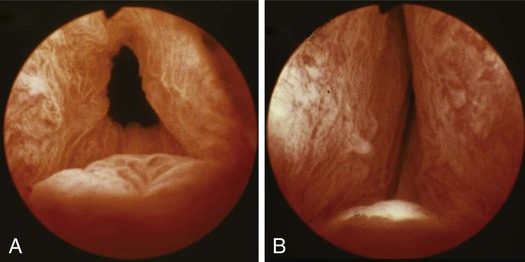

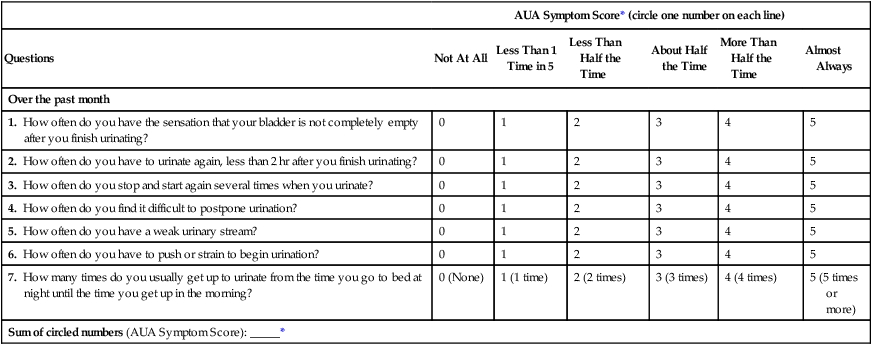

Chapter 55 1. Describe the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and collaborative care of benign prostatic hyperplasia. 2. Describe the nursing management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. 3. Describe the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and collaborative care of prostate cancer. 4. Explain the nursing management of prostate cancer. 5. Specify the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and collaborative management of prostatitis and problems of the penis and scrotum. 6. Explain the clinical manifestations and collaborative care of testicular cancer. 7. Describe the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and collaborative management of problems related to male sexual function. 8. Summarize the psychologic and emotional implications related to male reproductive problems. This chapter discusses problems of the male reproductive system. These involve a variety of structures, including the prostate, penis, urethra, ejaculatory duct, scrotum, testes, epididymis, ductus (vas) deferens, and rectum (Fig. 55-1). Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a benign enlargement of the prostate gland. It is the most common urologic problem in male adults. About 50% of all men in their lifetime will develop BPH. Of these men, almost half of them will have bothersome lower urinary tract symptoms.1 Research is not clear about whether having BPH leads to an increased risk of developing prostate cancer.2,3 Although the cause of BPH is not completely understood, it is thought that BPH results from hormonal changes associated with the aging process.1 One possible cause is excessive accumulation of dihydroxytestosterone (DHT) (the principal intraprostatic androgen) in the prostate cells. This can stimulate cell growth and an overgrowth of prostate tissue. Older men have a decrease in the blood’s testosterone level, but continue to produce and accumulate high levels of DHT in the prostate. Typically BPH develops in the inner part of the prostate. (Prostate cancer is most likely to develop in the outer part.) This enlargement gradually compresses the urethra, eventually leading to partial or complete obstruction (Fig. 55-2). The compression of the urethra ultimately leads to the development of clinical symptoms. There is no direct relationship between the size of the prostate and the severity of symptoms or degree of obstruction. The location of the enlargement is most significant in the development of obstructive symptoms (Fig. 55-3). For example, it is possible for mild hyperplasia to cause severe obstruction, or for extreme hyperplasia to cause few obstructive symptoms. Risk factors for BPH include aging, obesity (in particular increased waist circumference), lack of physical activity, alcohol consumption, erectile dysfunction, smoking, and diabetes.4 A positive family history of BPH in first-degree relatives may also be a risk factor. Manifestations of BPH are mainly associated with symptoms of the lower urinary tract.5 The patient’s symptoms are usually gradual in onset and may not be noticed until prostatic enlargement has been present for some time. Early symptoms are often minimal because the bladder can compensate for a small amount of resistance to urine flow. The symptoms gradually worsen as the degree of urethral obstruction increases. Symptoms can be divided into two groups: irritative and obstructive. Irritative symptoms, which include nocturia, urinary frequency, urgency, dysuria, bladder pain, and incontinence, are associated with inflammation or infection. Nocturia is often the first symptom that the patient notices.5 The American Urological Association (AUA) symptom index for BPH (Table 55-1) is a widely used tool to assess voiding symptoms associated with obstruction. Although this tool is not diagnostic, it helps determine the extent of symptoms.6 Higher scores on this tool indicate greater symptom severity. TABLE 55-1 AUA SYMPTOM INDEX TO DETERMINE SEVERITY OF PROSTATIC PROBLEMS AUA, American Urological Association. *Score is interpreted as follows: 0-7, mild; 8-19, moderate; 20-35, severe. Source: Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, O’Leary MP, et al: The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia, J Urol 148:1549, 1992. Used with permission. The primary methods used to diagnose BPH include a history and physical examination. (Diagnostic studies are outlined in Table 55-2.) The prostate can be palpated by digital rectal examination (DRE) to estimate its size, symmetry, and consistency. In BPH, the prostate is symmetrically enlarged, firm, and smooth. TABLE 55-2 COLLABORATIVE CARE The most conservative treatment that may be recommended for some patients with BPH is referred to as active surveillance, or watchful waiting.7 When the patient has no symptoms or only mild ones (AUA symptom scores of 0 to 7), a wait-and-see approach is taken. Because some patients have symptoms that disappear, a conservative approach has value. Making dietary changes (decreasing intake of caffeine, artificial sweeteners, and spicy or acidic foods), avoiding medications such as decongestants and anticholinergics, and restricting evening fluid intake may improve symptoms. These drugs work by reducing the size of the prostate gland. Finasteride (Proscar) blocks the enzyme 5α-reductase, which is necessary for the conversion of testosterone to DHT, the principal intraprostatic androgen. This drug results in regression of hyperplastic tissue through suppression of androgens. Finasteride is an appropriate treatment option for individuals who have a moderate to severe symptom score on the AUA symptom index (see Table 55-1). Although more than 50% of men who are treated with the drug show symptom improvement, it takes about 6 months to be effective. Furthermore, the drug must be taken on a continuous basis to maintain therapeutic results. Serum PSA levels are decreased by almost 50% when taking finasteride. Therefore PSA levels should be doubled when comparing the patient’s current levels to premedication levels. In addition to decreasing the symptoms of BPH, finasteride, dutasteride, and Jalyn (finasteride plus tamsulosin) may also lower the risk of prostate cancer.8 However, the use of these drugs in prevention of prostate cancer has not been advised because of the increased risk of developing aggressive prostate cancer. Patients with an increased PSA level while taking these medications should be referred to their health care provider. The need for regular prostate cancer screening should also be discussed with the provider. Herbal extracts have been used in the management of lower urinary symptoms associated with BPH. In particular, some patients take plant extracts such as saw palmetto (Serenoa repens). However, research indicates that saw palmetto has no benefit over a placebo.10,11 In a limited number of small trials, herbal preparations such as saxifrage, beta-sitosterol, Pygeum africanum, and Cernilton have shown some success in reducing the symptoms of BPH. Advise patients to tell their health care provider about all herbal supplements that they use. Minimally invasive therapies are becoming more common as an alternative to watchful waiting and invasive treatment (Table 55-3). They generally do not require hospitalization or catheterization and are associated with few adverse events. Many minimally invasive therapies have outcomes comparable to those of invasive techniques.12 TABLE 55-3 TREATMENT FOR BENIGN PROSTATIC HYPERPLASIA The use of laser therapy through visual or ultrasound guidance is an effective alternative to transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) in treating BPH. The laser beam is delivered transurethrally through a fiber instrument and is used for cutting, coagulation, and vaporization of prostatic tissue. There are a variety of laser procedures using different sources, wavelengths, and delivery systems. Retreatment rates are comparable to those of a TURP.13 Invasive treatment of symptomatic BPH involves surgery. The choice of the treatment approach depends on the size and location of the prostatic enlargement and patient factors such as age and surgical risk. Invasive treatments are summarized in Table 55-3. Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) is a surgical procedure involving the removal of prostate tissue using a resectoscope inserted through the urethra. TURP has long been considered the gold standard for surgical treatments of obstructing BPH. Although this procedure remains the most common operation performed, the number of TURP procedures done in recent years has declined due to the development of less invasive technologies.12 TURP is performed under a spinal or general anesthetic and requires a 1- to 2-day hospital stay. No external surgical incision is made. A resectoscope is inserted through the urethra to excise and cauterize obstructing prostatic tissue (Fig. 55-4). A large three-way indwelling catheter with a 30-mL balloon is inserted into the bladder after the procedure to provide hemostasis and to facilitate urinary drainage. The bladder is irrigated, either continuously or intermittently, usually for the first 24 hours to prevent obstruction from mucus and blood clots. Subjective and objective data that should be obtained from a patient with BPH are presented in Table 55-4. TABLE 55-4 NURSING ASSESSMENT Subjective Data Important Health Information Medications: Estrogen or testosterone supplementation Surgery or other treatments: Previous treatment for BPH Functional Health Patterns Health perception–health management: Knowledge of the condition Nutritional-metabolic: Voluntary fluid restriction Elimination: Urinary urgency, diminution in caliber and force of urinary stream; hesitancy in initiating voiding; postvoid dribbling; urinary retention; incontinence Sleep: Nocturia Cognitive-perceptual: Dysuria, sensation of incomplete voiding; bladder discomfort Sexuality-reproductive: Anxiety about sexual dysfunction Objective Data General Older adult male Urinary Distended bladder on palpation; smooth, firm, elastic enlargement of prostate on rectal examination Possible Diagnostic Findings Enlarged prostate on ultrasonography; vesicle neck obstruction on cystoscopy; residual urine with postvoiding catheterization; white blood cells, bacteria, or microscopic hematuria with infection; ↑ serum creatinine levels with renal involvement The cause of BPH is largely attributed to the aging process.14 Health promotion focuses on early detection and treatment. The American Cancer Society, along with the AUA, recommends a yearly medical history and DRE for men over 50 years of age in an effort to detect prostate problems early. When symptoms of prostatic hyperplasia are present, further diagnostic screening may be necessary (see Table 55-2). Urinary drainage must be restored before surgery. Prostatic obstruction may result in acute retention or inability to void. A urethral catheter such as a coudé (curved-tip) catheter may be needed to restore drainage. In many health care settings, 10 mL of sterile 2% lidocaine gel is injected into the urethra before insertion of the catheter. The lidocaine gel not only acts as a lubricant, but also provides local anesthesia and helps open the urethral lumen. If a sizable obstruction of the urethra exists, the urologist may insert a filiform catheter with sufficient rigidity to pass the obstruction. Aseptic technique is important at all times to avoid introducing bacteria into the bladder. (Urinary catheters are discussed in Chapter 46.) The catheter is often removed 2 to 4 days after surgery. The patient should urinate within 6 hours after catheter removal. If he cannot, reinsert a catheter for a day or two. If the problem continues, instruct the patient to perform clean intermittent self-catheterization (see Chapter 46). Sphincter tone may be poor immediately after catheter removal, resulting in urinary incontinence or dribbling. This is a common but distressing situation for the patient. Sphincter tone can be strengthened by having the patient practice Kegel exercises (pelvic floor muscle technique) 10 to 20 times per hour while awake. (Kegel exercises are discussed in Table 46-19.) Encourage the patient to practice starting and stopping the stream several times during urination. This facilitates learning the pelvic floor exercises. Prostate cancer is a malignant tumor of the prostate gland. It is estimated that 241,740 new cases of prostate cancer are diagnosed and 28,170 men die annually from the disease in the United States.15 One of every six men will develop prostate cancer at some point during his life. Prostate cancer is the most common cancer among men, excluding skin cancer. It is the second leading cause of cancer death in men (exceeded only by lung cancer). The majority (more than 60%) of cases occur in men over age 65. However, many cases occur in younger men who sometimes have a more aggressive type of cancer. Almost 2.8 million men in the United States are survivors of prostate cancer.16 Age, ethnicity, and family history are known risk factors for prostate cancer. (Additional information on ethnicity is presented in the Cultural & Ethnic Health Disparities box on this page.) The incidence of prostate cancer rises markedly after age 50 with a median age at diagnosis of 67 years old.16 The incidence of prostate cancer worldwide is higher in African Americans than in any other ethnic group (except Jamaican men of African descent).15 The reasons for the higher rate are unknown. In addition, African American men are likely to have more aggressive tumors at diagnosis and have higher mortality rates from prostate cancer. Differences in survival may be due to body composition, dietary factors, and endogenous hormones.

Nursing Management

Male Reproductive Problems

Problems of the Prostate Gland

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Clinical Manifestations

AUA Symptom Score* (circle one number on each line)

Questions

Not At All

Less Than 1 Time in 5

Less Than Half the Time

About Half the Time

More Than Half the Time

Almost Always

Over the past month

1. How often do you have the sensation that your bladder is not completely empty after you finish urinating?

0

1

2

3

4

5

2. How often do you have to urinate again, less than 2 hr after you finish urinating?

0

1

2

3

4

5

3. How often do you stop and start again several times when you urinate?

0

1

2

3

4

5

4. How often do you find it difficult to postpone urination?

0

1

2

3

4

5

5. How often do you have a weak urinary stream?

0

1

2

3

4

5

6. How often do you have to push or strain to begin urination?

0

1

2

3

4

5

7. How many times do you usually get up to urinate from the time you go to bed at night until the time you get up in the morning?

0 (None)

1 (1 time)

2 (2 times)

3 (3 times)

4 (4 times)

5 (5 times or more)

Sum of circled numbers (AUA Symptom Score): _____*

Diagnostic Studies

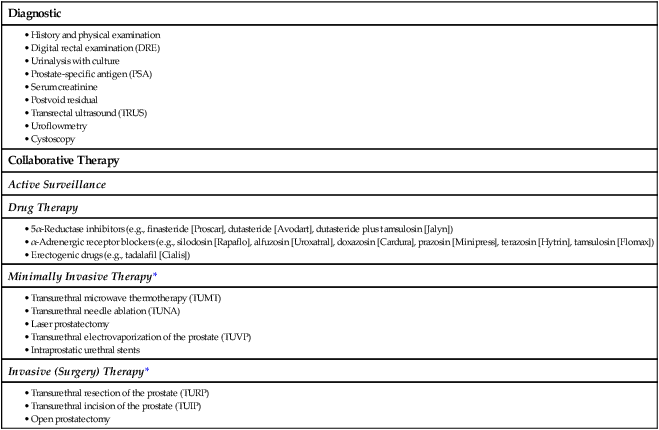

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Diagnostic

Collaborative Therapy

Active Surveillance

Drug Therapy

Minimally Invasive Therapy*

Invasive (Surgery) Therapy*

Collaborative Care

Drug Therapy.

5α-Reductase Inhibitors.

Herbal Therapy.

Minimally Invasive Therapy.

Description

Advantages

Disadvantages

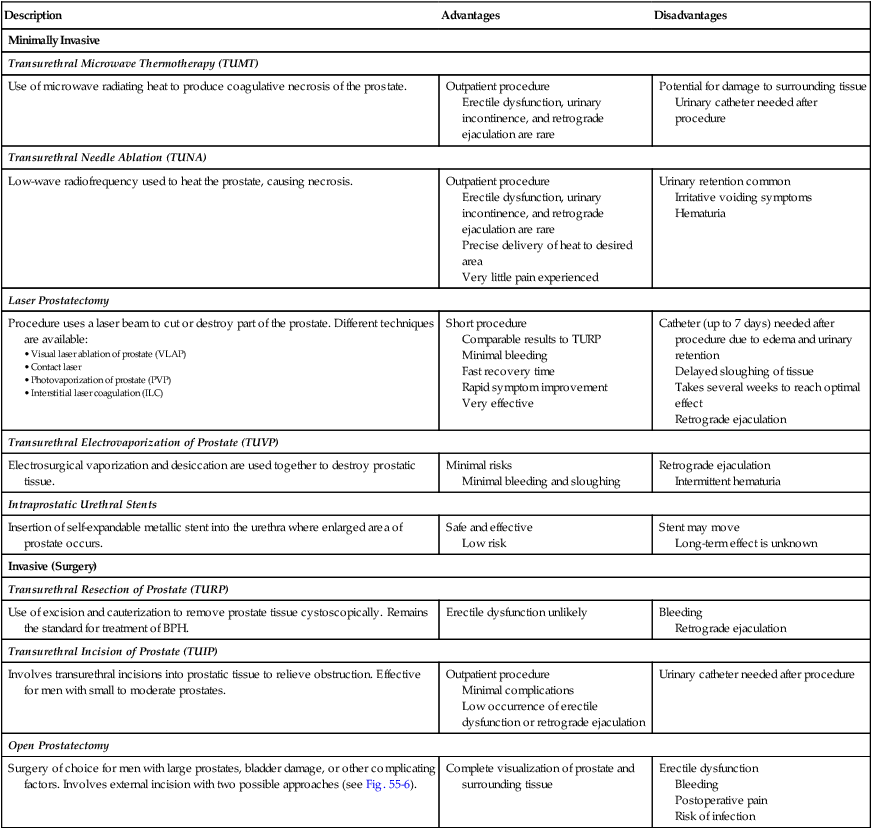

Minimally Invasive

Transurethral Microwave Thermotherapy (TUMT)

Use of microwave radiating heat to produce coagulative necrosis of the prostate.

Outpatient procedure

Erectile dysfunction, urinary incontinence, and retrograde ejaculation are rare

Potential for damage to surrounding tissue

Urinary catheter needed after procedure

Transurethral Needle Ablation (TUNA)

Low-wave radiofrequency used to heat the prostate, causing necrosis.

Outpatient procedure

Erectile dysfunction, urinary incontinence, and retrograde ejaculation are rare

Precise delivery of heat to desired area

Very little pain experienced

Urinary retention common

Irritative voiding symptoms

Hematuria

Laser Prostatectomy

Procedure uses a laser beam to cut or destroy part of the prostate. Different techniques are available:

Short procedure

Comparable results to TURP

Minimal bleeding

Fast recovery time

Rapid symptom improvement

Very effective

Catheter (up to 7 days) needed after procedure due to edema and urinary retention

Delayed sloughing of tissue

Takes several weeks to reach optimal effect

Retrograde ejaculation

Transurethral Electrovaporization of Prostate (TUVP)

Electrosurgical vaporization and desiccation are used together to destroy prostatic tissue.

Minimal risks

Minimal bleeding and sloughing

Retrograde ejaculation

Intermittent hematuria

Intraprostatic Urethral Stents

Insertion of self-expandable metallic stent into the urethra where enlarged area of prostate occurs.

Safe and effective

Low risk

Stent may move

Long-term effect is unknown

Invasive (Surgery)

Transurethral Resection of Prostate (TURP)

Use of excision and cauterization to remove prostate tissue cystoscopically. Remains the standard for treatment of BPH.

Erectile dysfunction unlikely

Bleeding

Retrograde ejaculation

Transurethral Incision of Prostate (TUIP)

Involves transurethral incisions into prostatic tissue to relieve obstruction. Effective for men with small to moderate prostates.

Outpatient procedure

Minimal complications

Low occurrence of erectile dysfunction or retrograde ejaculation

Urinary catheter needed after procedure

Open Prostatectomy

Surgery of choice for men with large prostates, bladder damage, or other complicating factors. Involves external incision with two possible approaches (see Fig. 55-6).

Complete visualization of prostate and surrounding tissue

Erectile dysfunction

Bleeding

Postoperative pain

Risk of infection

Laser Prostatectomy.

Invasive Therapy (Surgery).

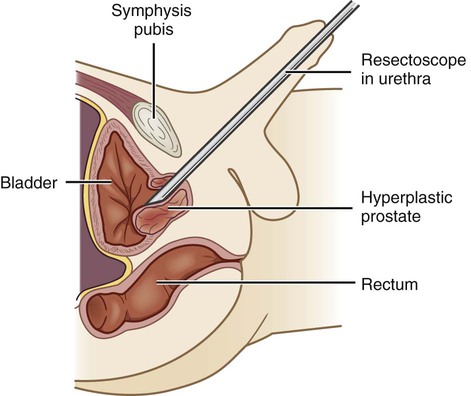

Transurethral Resection of the Prostate.

Nursing Management Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Nursing Assessment

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Nursing Implementation

Health Promotion.

Acute Intervention.

Preoperative Care.

Postoperative Care.

Prostate Cancer

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Nursing Management: Male Reproductive Problems

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access