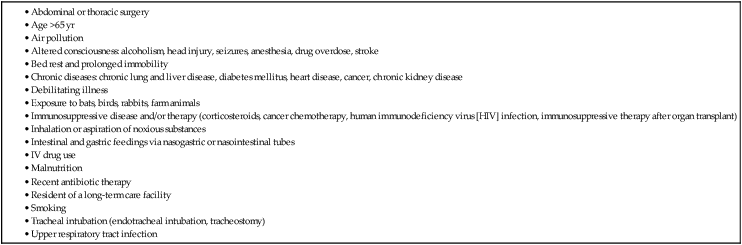

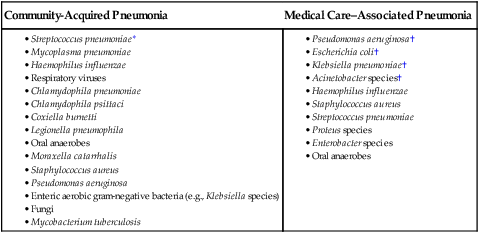

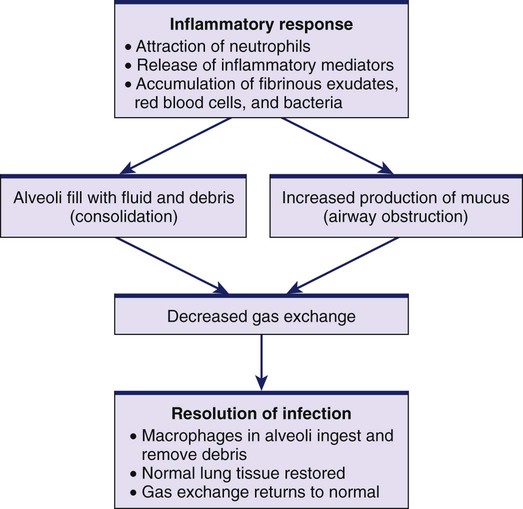

1. Compare and contrast the clinical manifestations and collaborative and nursing management of patients with acute bronchitis and pertussis. 2. Differentiate among the types of pneumonia and their etiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and collaborative care. 3. Prioritize the nursing management of the patient with pneumonia. 4. Describe the pathogenesis, classification, clinical manifestations, complications, diagnostic abnormalities, and nursing and collaborative management of patients with tuberculosis. 5. Describe the causes, clinical manifestations, and collaborative management of patients with pulmonary fungal infections. 6. Explain the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and collaborative management of patients with lung abscesses. 7. Identify the causative factors, clinical manifestations, and nursing and collaborative management of patients with environmental lung diseases. 8. Describe the etiology, risk factors, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and collaborative management of lung cancer. 9. Compare and contrast the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and collaborative management of pneumothorax, fractured ribs, and flail chest. 10. Describe the purpose, function, and nursing responsibilities related to chest tubes and various drainage systems. 11. Explain the types of chest surgery and appropriate preoperative and postoperative care. 12. Describe the etiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and collaborative management of patients with restrictive lung disorders such as pleural effusion, pleurisy, and atelectasis. 13. Describe the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management of pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension, and cor pulmonale. 14. Discuss the use of lung transplantation as a treatment for pulmonary disorders. eTABLE 28-1 CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; ICU, intensive care unit. eTABLE 28-2 TRAUMATIC CHEST INJURIES AND MECHANISMS OF INJURY eTABLE 28-3 CAUSES OF RESTRICTIVE LUNG DISEASE A wide variety of problems affect the lower respiratory system. Lung diseases that are characterized primarily by an obstructive disorder, such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and cystic fibrosis, are discussed in Chapter 29. This chapter discusses other lower respiratory tract diseases, including infectious, oncologic, traumatic, restrictive, and vascular disorders. Lower respiratory tract infection is both a common and a serious occurrence. It is the third leading cause of death worldwide.1 Pneumonia and influenza are the eighth leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for more than 56,000 deaths annually.2 Acute bronchitis is an inflammation of the bronchi in the lower respiratory tract. Up to 90% of acute bronchial infections are viral in origin. Cough, which is the most common symptom, lasts for up to 3 weeks. Clear, mucoid sputum is often present, although some patients produce purulent sputum. The presence of colored (e.g., green) sputum is not a reliable indicator of bacterial infection.3 Associated symptoms include headache, fever, malaise, hoarseness, myalgias, dyspnea, and chest pain. Assessment may reveal normal breath sounds or rhonchi, crackles, or wheezes, usually with expiration and exertion. Diagnosis is based on clinical assessment. Evidence of consolidation (e.g., fremitus, rales, egophony), which is suggestive of pneumonia, is absent with bronchitis. (Consolidation in the lungs occurs when fluid accumulates, causing the lung tissue to become stiff and unable to exchange gases.) Chest x-rays would be normal and are therefore not indicated unless pneumonia is suspected. (Chronic bronchitis is discussed in Chapter 29.) Acute bronchitis is usually self-limiting, and treatment is supportive. Cough suppressants, β2-agonist (bronchodilator) inhalers in patients with wheezing, and high-dose inhaled corticosteroids may be used.3 Antibiotics generally are not prescribed unless the person has a prolonged infection associated with systemic symptoms. Explain to the patient that antibiotics are not effective in treating a viral infection and that they may cause side effects and antibiotic-resistant germs. Complementary and alternative therapies (e.g., echinacea, honey) may be useful for symptom relief. If the acute bronchitis is due to an influenza virus, treatment with antiviral drugs, either zanamivir (Relenza) or oseltamivir (Tamiflu), can be started. These drugs should be initiated within 48 hours of the onset of symptoms. Pertussis is a highly contagious infection of the respiratory tract caused by a gram-negative bacillus, Bordetella pertussis. Pertussis is characterized by uncontrollable, violent coughing. Despite improved childhood vaccination in the United States, the incidence of pertussis has been steadily increasing since the 1980s, with the largest increase noted in adults.4 It is thought that immunity resulting from childhood vaccination with DPT (diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus) may wane over time, resulting in a milder infection that is still distressing and contagious. Therefore the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) currently recommends that all adults age 18 years and older receive a one-time dose of Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis) vaccination.4 Pneumonia is an acute infection of the lung parenchyma. Until 1936, pneumonia was the leading cause of death in the United States. The discovery of sulfa drugs and penicillin was pivotal in the treatment of pneumonia. Since that time, remarkable progress has been made in the development of antibiotics to treat pneumonia. However, despite new antimicrobial agents, pneumonia is still associated with significant morbidity and mortality rates. Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is the sixth leading cause of death for people ages 65 years or older in the United States.5 Normally, the airway distal to the larynx is protected from infection by various defense mechanisms. Mechanisms that create a mechanical barrier to microorganisms include air filtration, epiglottis closure over the trachea, cough reflex, mucociliary escalator mechanism, and reflex bronchoconstriction (see Chapter 26). Immune defense mechanisms include secretion of immunoglobulins A and G and alveolar macrophages. Pneumonia is more likely to occur when the defense mechanisms become incompetent or are overwhelmed by the virulence or quantity of infectious agents. Decreased consciousness depresses the cough and epiglottal reflexes, which may allow aspiration of oropharyngeal contents into the lungs. Tracheal intubation interferes with the normal cough reflex and the mucociliary escalator mechanism. Air pollution, cigarette smoking, viral URIs, and normal changes that occur with aging can impair the mucociliary mechanism. Chronic diseases can suppress the immune system’s ability to inhibit bacterial growth. The risk factors for pneumonia are listed in Table 28-1. TABLE 28-1 Organisms that cause pneumonia reach the lung by three methods: 1. Aspiration of normal flora from the nasopharynx or oropharynx. Many of the organisms that cause pneumonia are normal inhabitants of the pharynx in healthy adults. 2. Inhalation of microbes present in the air. Examples include Mycoplasma pneumoniae and fungal pneumonias. 3. Hematogenous spread from a primary infection elsewhere in the body. An example is Staphylococcus aureus. Bacteria, viruses, Mycoplasma organisms, fungi, parasites, and chemicals are all potential causes of pneumonia. Although pneumonia can be classified according to the causative organism, a clinically effective way is to classify it as community-acquired or medical care–associated pneumonia. Classifying pneumonia is important because of the differences in the likely causative organisms (Table 28-2) and the selection of appropriate antimicrobial therapy. TABLE 28-2 *Most common cause of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP). †Most common causes of medical care–associated pneumonia (MCAP). Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is an acute infection of the lung occurring in patients who have not been hospitalized or resided in a long-term care facility within 14 days of the onset of symptoms.5 The decision to treat the patient at home or admit him or her to the hospital is based on several factors such as the patient’s age, vital signs, mental status, and presence of co-morbid conditions. Clinicians can use tools such as the CURB-65 scale (Table 28-3) or the Pneumonia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) to supplement clinical judgment. (The PSI calculator is available online at http://pda.ahrq.gov/clinic/psi/psicalc.asp). Empiric antibiotic therapy should be started as soon as possible. (Empiric therapy is the initiation of treatment before a definitive diagnosis. It is based on experience and knowledge of drugs known to be effective for the likely causative agent.) TABLE 28-3 ASSESSING PNEUMONIA USING CURB-65 Source: Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R, et al: Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study, Thorax 58(5):377, 2003. Medical care–associated pneumonia (MCAP) encompasses three forms of pneumonia: hospital-associated pneumonia, ventilator-associated pneumonia, and health care–associated pneumonia.6 Hospital-associated pneumonia (HAP) is pneumonia that occurs 48 hours or longer after hospital admission and was not incubating at the time of hospitalization. Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) refers to pneumonia that occurs more than 48 hours after endotracheal intubation. (VAP is discussed in Chapter 66.) Health care–associated pneumonia (HCAP) is a new-onset pneumonia in a patient who (1) was hospitalized in an acute care hospital for 2 days or longer within 90 days of the infection; (2) resided in a long-term care facility; (3) received IV antibiotic therapy, chemotherapy, or wound care within the past 30 days of the current infection; or (4) attended a hospital or hemodialysis clinic.6 A major problem in treating MCAP is multidrug-resistant (MDR) organisms. Antibiotic susceptibility tests can identify MDR organisms. The virulence of these organisms can severely limit the available and appropriate antimicrobial therapy. In addition, MDR organisms can increase the morbidity and mortality risks associated with pneumonia. (Chapter 15 discusses MDR organisms.) Aspiration pneumonia, occurring as either CAP or MCAP, results from the abnormal entry of material from the mouth or stomach into the trachea and lungs. Conditions that increase the risk of aspiration include decreased level of consciousness (e.g., seizure, anesthesia, head injury, stroke, alcohol intake), difficulty swallowing, and nasogastric intubation with or without tube feeding. With loss of consciousness, the gag and cough reflexes are depressed, and aspiration is more likely to occur. Other high-risk groups are those who are seriously ill, have poor dentition, or are receiving acid-reducing medications.7 CMV, a herpes virus, can cause viral pneumonia. Most CMV infections are asymptomatic or mild, but severe disease can occur in people with an impaired immune response. CMV is the most common life-threatening infectious complication after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.8 Antiviral medications (e.g., ganciclovir [Cytovene], foscarnet [Foscavir], cidofovir [Vistide]) and high-dose immunoglobulin are used for treatment. Specific pathophysiologic changes related to pneumonia vary according to the offending organism. Some viruses cause direct injury and cell death. The majority of organisms, however, trigger an inflammatory response in the lung (Fig. 28-1). A vascular reaction occurs, characterized by an increase in blood flow and vascular permeability. Neutrophils are activated to engulf and kill the offending organisms. The neutrophils, the offending organism, and fluid from surrounding blood vessels fill the alveoli and interrupt normal oxygen transportation, leading to clinical manifestations of hypoxia (e.g., tachypnea, dyspnea, tachycardia). Mucus production is also increased, which can obstruct airflow and further decrease gas exchange. Consolidation, a feature typical of bacterial pneumonia, occurs when the normally air-filled alveoli become filled with fluid and debris. Complete resolution and healing occur if there are no complications. Macrophages lyse and process the debris, normal lung tissue is restored, and gas exchange returns to normal. The most common presenting symptoms of pneumonia are cough, fever, shaking chills, dyspnea, tachypnea, and pleuritic chest pain. The cough may or may not be productive. Sputum may appear green, yellow, or even rust colored (bloody). Viral pneumonia may initially be seen as influenza, with respiratory symptoms appearing and/or worsening 12 to 36 hours after onset.9 The older or debilitated patient may not have classic symptoms of pneumonia. Confusion or stupor (possibly related to hypoxia) may be the only finding. Hypothermia, rather than fever, may also be noted with the older patient. Nonspecific clinical manifestations include diaphoresis, anorexia, fatigue, myalgias, headache, and abdominal pain. • Pleurisy (inflammation of the pleura) is relatively common. • Pleural effusion (fluid in the pleural space) can occur. In most cases, the effusion is sterile and is reabsorbed in 1 to 2 weeks. Occasionally, effusions require aspiration by thoracentesis. • Atelectasis (collapsed, airless alveoli) of one or part of one lobe may occur. These areas usually clear with effective coughing and deep breathing. • Bacteremia (bacterial infection in the blood) is more likely to occur in infections with Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae. • Lung abscess is not a common complication of pneumonia. However, it may occur with pneumonia caused by S. aureus and gram-negative organisms. • Empyema, the accumulation of purulent exudate in the pleural cavity, occurs in less than 5% of cases and requires antibiotic therapy and drainage of the exudate by a chest tube or open surgical drainage. • Pericarditis results from spread of the infecting organism from infected pleura or via a hematogenous route to the pericardium. • Meningitis can be caused by S. pneumoniae. The patient with pneumonia who is disoriented, confused, or drowsy may have a lumbar puncture to evaluate the possibility of meningitis. • Sepsis can occur when bacteria within alveoli enter the bloodstream. Severe sepsis can lead to shock and multisystem organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) (see Chapter 67). • Acute respiratory failure is one of the leading causes of death in patients with severe pneumonia. Failure occurs when pneumonia damages the lungs’ ability to exchange oxygen for carbon dioxide. • Pneumothorax can occur when air collects in the pleura space, causing the lungs to collapse.

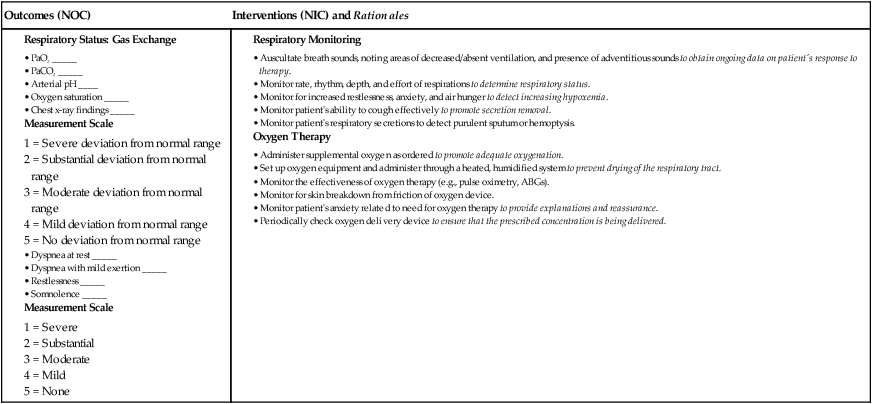

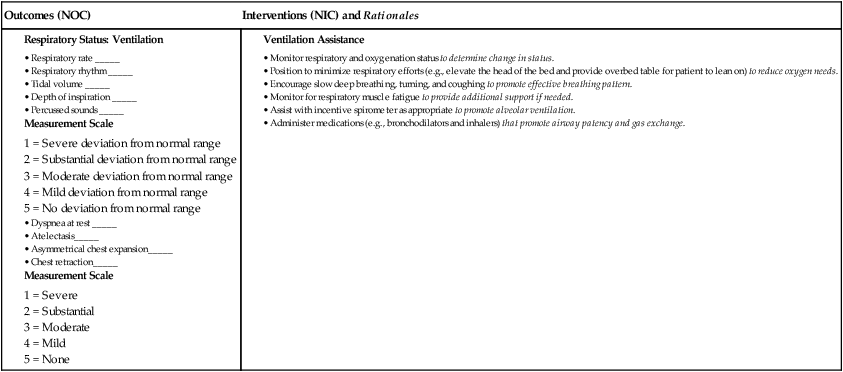

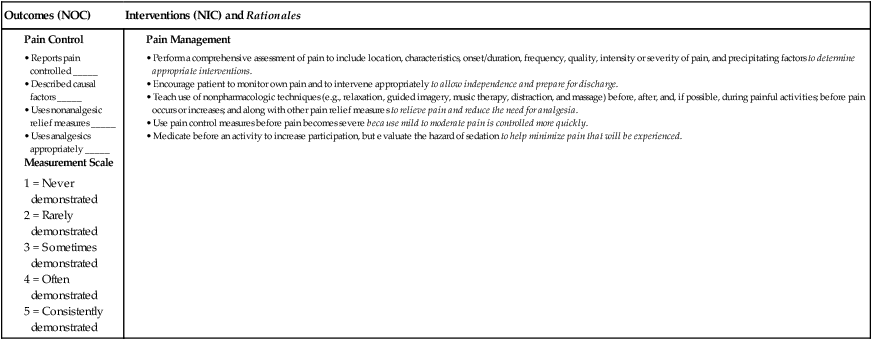

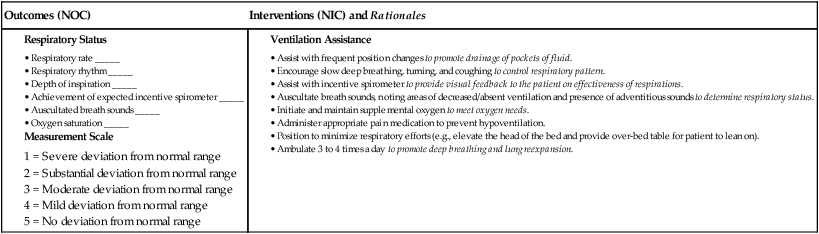

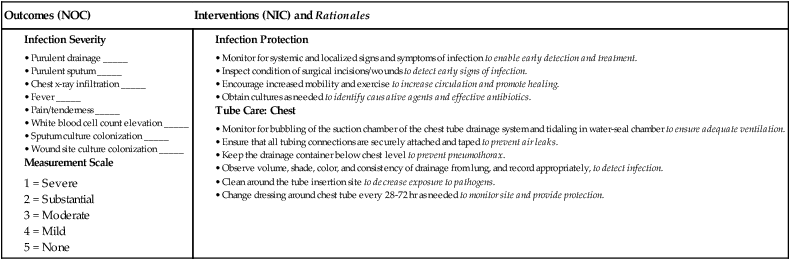

Nursing Management

Lower Respiratory Problems

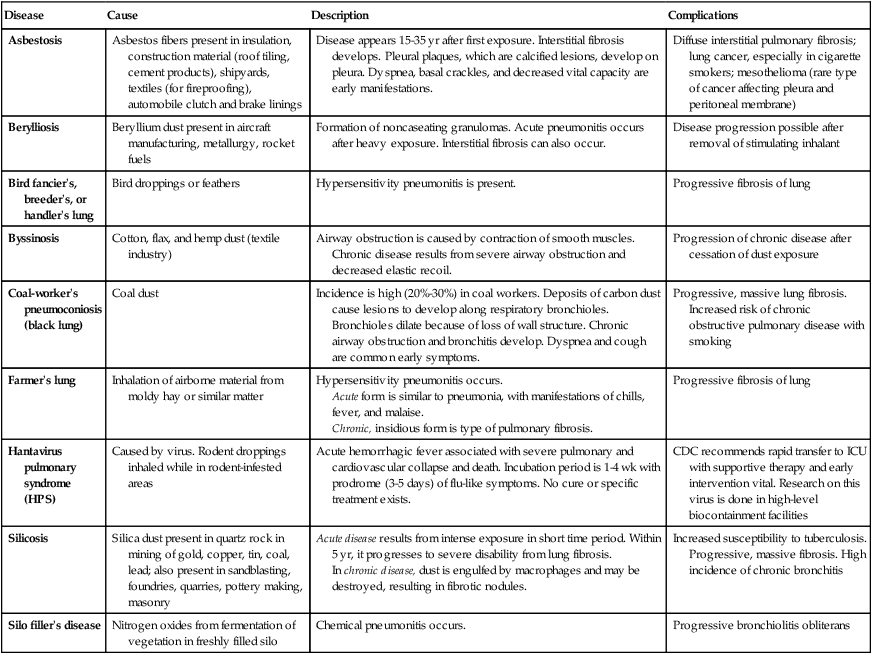

Disease

Cause

Description

Complications

Asbestosis

Asbestos fibers present in insulation, construction material (roof tiling, cement products), shipyards, textiles (for fireproofing), automobile clutch and brake linings

Disease appears 15-35 yr after first exposure. Interstitial fibrosis develops. Pleural plaques, which are calcified lesions, develop on pleura. Dyspnea, basal crackles, and decreased vital capacity are early manifestations.

Diffuse interstitial pulmonary fibrosis; lung cancer, especially in cigarette smokers; mesothelioma (rare type of cancer affecting pleura and peritoneal membrane)

Berylliosis

Beryllium dust present in aircraft manufacturing, metallurgy, rocket fuels

Formation of noncaseating granulomas. Acute pneumonitis occurs after heavy exposure. Interstitial fibrosis can also occur.

Disease progression possible after removal of stimulating inhalant

Bird fancier’s, breeder’s, or handler’s lung

Bird droppings or feathers

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis is present.

Progressive fibrosis of lung

Byssinosis

Cotton, flax, and hemp dust (textile industry)

Airway obstruction is caused by contraction of smooth muscles. Chronic disease results from severe airway obstruction and decreased elastic recoil.

Progression of chronic disease after cessation of dust exposure

Coal-worker’s pneumoconiosis (black lung)

Coal dust

Incidence is high (20%-30%) in coal workers. Deposits of carbon dust cause lesions to develop along respiratory bronchioles. Bronchioles dilate because of loss of wall structure. Chronic airway obstruction and bronchitis develop. Dyspnea and cough are common early symptoms.

Progressive, massive lung fibrosis. Increased risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with smoking

Farmer’s lung

Inhalation of airborne material from moldy hay or similar matter

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis occurs.

Acute form is similar to pneumonia, with manifestations of chills, fever, and malaise.

Chronic, insidious form is type of pulmonary fibrosis.

Progressive fibrosis of lung

Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS)

Caused by virus. Rodent droppings inhaled while in rodent-infested areas

Acute hemorrhagic fever associated with severe pulmonary and cardiovascular collapse and death. Incubation period is 1-4 wk with prodrome (3-5 days) of flu-like symptoms. No cure or specific treatment exists.

CDC recommends rapid transfer to ICU with supportive therapy and early intervention vital. Research on this virus is done in high-level biocontainment facilities

Silicosis

Silica dust present in quartz rock in mining of gold, copper, tin, coal, lead; also present in sandblasting, foundries, quarries, pottery making, masonry

Acute disease results from intense exposure in short time period. Within 5 yr, it progresses to severe disability from lung fibrosis.

In chronic disease, dust is engulfed by macrophages and may be destroyed, resulting in fibrotic nodules.

Increased susceptibility to tuberculosis. Progressive, massive fibrosis. High incidence of chronic bronchitis

Silo filler’s disease

Nitrogen oxides from fermentation of vegetation in freshly filled silo

Chemical pneumonitis occurs.

Progressive bronchiolitis obliterans

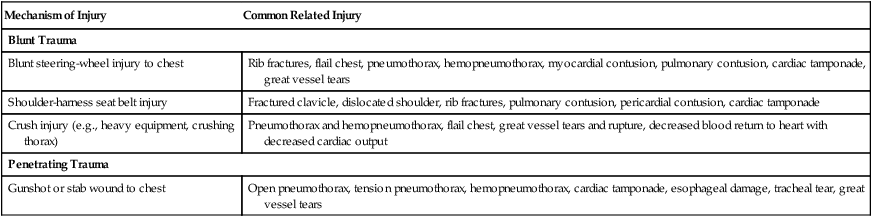

Mechanism of Injury

Common Related Injury

Blunt Trauma

Blunt steering-wheel injury to chest

Rib fractures, flail chest, pneumothorax, hemopneumothorax, myocardial contusion, pulmonary contusion, cardiac tamponade, great vessel tears

Shoulder-harness seat belt injury

Fractured clavicle, dislocated shoulder, rib fractures, pulmonary contusion, pericardial contusion, cardiac tamponade

Crush injury (e.g., heavy equipment, crushing thorax)

Pneumothorax and hemopneumothorax, flail chest, great vessel tears and rupture, decreased blood return to heart with decreased cardiac output

Penetrating Trauma

Gunshot or stab wound to chest

Open pneumothorax, tension pneumothorax, hemopneumothorax, cardiac tamponade, esophageal damage, tracheal tear, great vessel tears

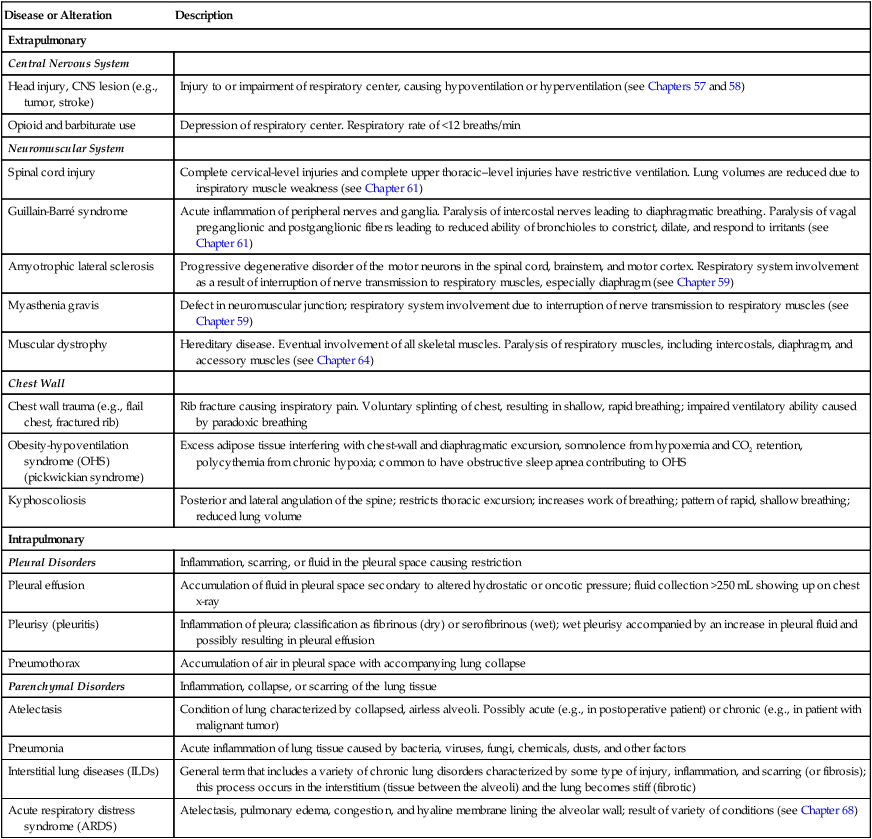

Disease or Alteration

Description

Extrapulmonary

Central Nervous System

Head injury, CNS lesion (e.g., tumor, stroke)

Injury to or impairment of respiratory center, causing hypoventilation or hyperventilation (see Chapters 57 and 58)

Opioid and barbiturate use

Depression of respiratory center. Respiratory rate of <12 breaths/min

Neuromuscular System

Spinal cord injury

Complete cervical-level injuries and complete upper thoracic–level injuries have restrictive ventilation. Lung volumes are reduced due to inspiratory muscle weakness (see Chapter 61)

Guillain-Barré syndrome

Acute inflammation of peripheral nerves and ganglia. Paralysis of intercostal nerves leading to diaphragmatic breathing. Paralysis of vagal preganglionic and postganglionic fibers leading to reduced ability of bronchioles to constrict, dilate, and respond to irritants (see Chapter 61)

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Progressive degenerative disorder of the motor neurons in the spinal cord, brainstem, and motor cortex. Respiratory system involvement as a result of interruption of nerve transmission to respiratory muscles, especially diaphragm (see Chapter 59)

Myasthenia gravis

Defect in neuromuscular junction; respiratory system involvement due to interruption of nerve transmission to respiratory muscles (see Chapter 59)

Muscular dystrophy

Hereditary disease. Eventual involvement of all skeletal muscles. Paralysis of respiratory muscles, including intercostals, diaphragm, and accessory muscles (see Chapter 64)

Chest Wall

Chest wall trauma (e.g., flail chest, fractured rib)

Rib fracture causing inspiratory pain. Voluntary splinting of chest, resulting in shallow, rapid breathing; impaired ventilatory ability caused by paradoxic breathing

Obesity-hypoventilation syndrome (OHS) (pickwickian syndrome)

Excess adipose tissue interfering with chest-wall and diaphragmatic excursion, somnolence from hypoxemia and CO2 retention, polycythemia from chronic hypoxia; common to have obstructive sleep apnea contributing to OHS

Kyphoscoliosis

Posterior and lateral angulation of the spine; restricts thoracic excursion; increases work of breathing; pattern of rapid, shallow breathing; reduced lung volume

Intrapulmonary

Pleural Disorders

Inflammation, scarring, or fluid in the pleural space causing restriction

Pleural effusion

Accumulation of fluid in pleural space secondary to altered hydrostatic or oncotic pressure; fluid collection >250 mL showing up on chest x-ray

Pleurisy (pleuritis)

Inflammation of pleura; classification as fibrinous (dry) or serofibrinous (wet); wet pleurisy accompanied by an increase in pleural fluid and possibly resulting in pleural effusion

Pneumothorax

Accumulation of air in pleural space with accompanying lung collapse

Parenchymal Disorders

Inflammation, collapse, or scarring of the lung tissue

Atelectasis

Condition of lung characterized by collapsed, airless alveoli. Possibly acute (e.g., in postoperative patient) or chronic (e.g., in patient with malignant tumor)

Pneumonia

Acute inflammation of lung tissue caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi, chemicals, dusts, and other factors

Interstitial lung diseases (ILDs)

General term that includes a variety of chronic lung disorders characterized by some type of injury, inflammation, and scarring (or fibrosis); this process occurs in the interstitium (tissue between the alveoli) and the lung becomes stiff (fibrotic)

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

Atelectasis, pulmonary edema, congestion, and hyaline membrane lining the alveolar wall; result of variety of conditions (see Chapter 68)

Lower Respiratory Tract Infections

Acute Bronchitis

Pertussis

Pneumonia

Etiology

Types of Pneumonia

Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Medical Care–Associated Pneumonia

Community-Acquired Pneumonia.

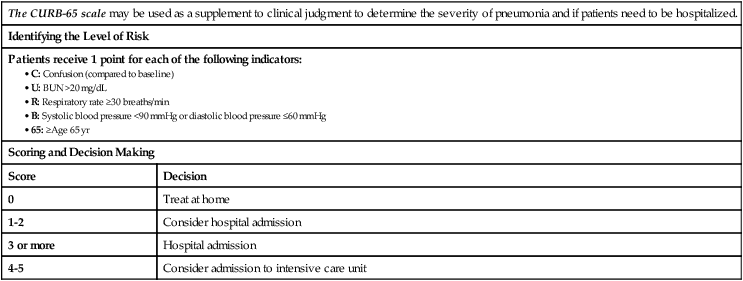

The CURB-65 scale may be used as a supplement to clinical judgment to determine the severity of pneumonia and if patients need to be hospitalized.

Identifying the Level of Risk

Patients receive 1 point for each of the following indicators:

Scoring and Decision Making

Score

Decision

0

Treat at home

1-2

Consider hospital admission

3 or more

Hospital admission

4-5

Consider admission to intensive care unit

Medical Care–Associated Pneumonia.

Aspiration Pneumonia.

Opportunistic Pneumonia.

Pathophysiology

Clinical Manifestations

Complications

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nursing Management: Lower Respiratory Problems

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access