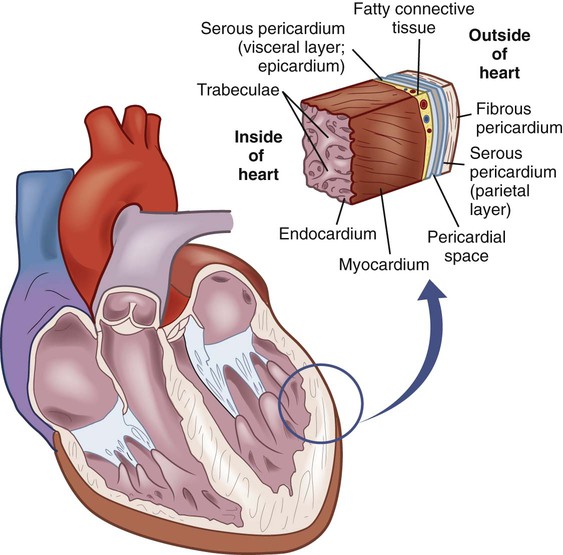

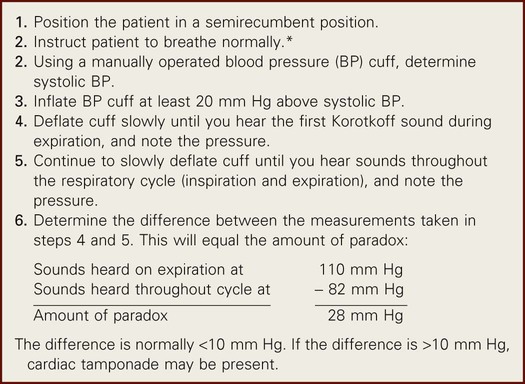

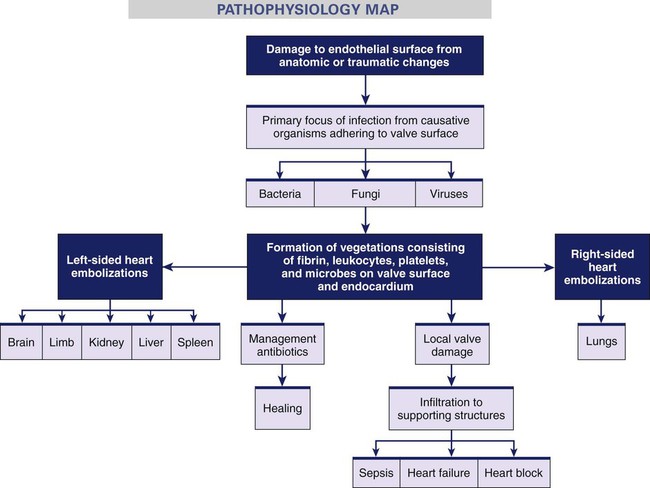

Nancy Kupper and De Ann F. Mitchell 1. Differentiate the etiology, pathophysiology, and clinical manifestations of infective endocarditis and pericarditis. 2. Describe the collaborative care and nursing management of the patient with infective endocarditis and pericarditis. 3. Describe the etiology, pathophysiology, and clinical manifestations of myocarditis. 4. Describe the collaborative care and nursing management of the patient with myocarditis. 5. Differentiate the etiology, pathophysiology, and clinical manifestations of rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. 6. Describe the collaborative care and nursing management of the patient with rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. 7. Relate the pathophysiology to the clinical manifestations and diagnostic studies for the various types of valvular heart disease. 8. Describe the collaborative care and nursing management of the patient with valvular heart disease. 9. Relate the pathophysiology to the clinical manifestations and diagnostic studies for the different types of cardiomyopathy. 10. Compare the nursing and collaborative management of patients with different types of cardiomyopathy. Infective endocarditis (IE) is an infection of the endocardial layer of the heart. The endocardium is the innermost layer of the heart (Fig. 37-1) and heart valves. Therefore IE affects the valves. Treatment of IE with antibiotic therapy has improved the prognosis of this disease. Though relatively uncommon, an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 new cases of IE are diagnosed in the United States each year.1 The most common causative organisms of IE, Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus viridans, are bacterial. Other possible pathogens include fungi and viruses.2 IE occurs when blood turbulence within the heart allows the causative organism to infect previously damaged valves or other endothelial surfaces. This can occur in individuals with a variety of underlying cardiac and noncardiac conditions (Table 37-1). TABLE 37-1 RISK FACTORS FOR ENDOCARDITIS* Vegetations, the primary lesions of IE, consist of fibrin, leukocytes, platelets, and microbes that stick to the valve surface or endocardium (Fig. 37-2). The loss of parts of these fragile vegetations into the circulation results in emboli. As many as 50% of patients with IE experience systemic embolization. This occurs from left-sided heart vegetation moving to various organs (e.g., brain, kidneys, spleen) and to the extremities, causing limb infarction. Right-sided heart lesions move to the lungs, resulting in pulmonary emboli. The infection may spread locally and damage the valves or their supporting structures. This causes dysrhythmias, valve dysfunction, and eventual invasion of the myocardium, leading to heart failure (HF), sepsis, and heart block (Fig. 37-3). At one time rheumatic heart disease was the most common cause of IE. However, now it accounts for less than 20% of cases. The main contributing factors to IE include (1) aging (more than 50% of older people have aortic stenosis [AS]), (2) IVDA, (3) use of prosthetic valves, (4) use of intravascular devices resulting in health care–associated infections (e.g., methicillin-resistant S. aureus [MRSA]), and (5) renal dialysis.3 The onset of a new or changing murmur is noted in most patients with IE. The aortic and mitral valves are most often affected. Murmurs are usually absent in tricuspid endocarditis because right-sided heart sounds are too low to be heard. HF occurs in up to 80% of patients with aortic valve endocarditis and in approximately 50% of patients with mitral valve endocarditis.4 Major criteria to diagnose IE include at least two of the following: positive blood cultures, new or changed heart murmur, or intracardiac mass or vegetation noted on echocardiography.5 Echocardiography is valuable in the diagnostic workup for a patient with IE when the blood cultures are negative, or for the patient who is a surgical candidate and has an active infection. Transesophageal echocardiogram and two- or three-dimensional (2-D or 3-D) transthoracic echocardiograms can detect vegetations on the heart valves.6 A chest x-ray is done to detect cardiomegaly (an enlarged heart). An electrocardiogram (ECG) may show first- or second-degree atrioventricular (AV) block. Heart block occurs because the cardiac valves lie close to conductive tissue, especially the AV node. Cardiac catheterization may be used to evaluate valve functioning and to assess the coronary arteries when surgical intervention is being considered.7 The situations and conditions requiring antibiotic prophylaxis are presented in Table 37-2. TABLE 37-2 ANTIBIOTIC PROPHYLAXIS TO PREVENT ENDOCARDITIS • Prosthetic heart valve or prosthetic material used to repair heart valve • Previous history of infectious endocarditis • Congenital heart disease (CHD)* • Unrepaired cyanotic CHD (including palliative shunts and conduits) • Repaired congenital heart defect with prosthetic material or device for 6 mo after the procedure • Repaired CHD with residual defects at the site or adjacent to the site of prosthetic patch or prosthetic device • Cardiac transplantation recipients who develop heart valve disease *Except for the conditions listed above, prophylaxis is no longer recommended for any form of CHD. Source: Habib G, Hoen B, Tornos P, et al: Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of infective endocarditis (new version 2009): the Task Force on the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), Eur Heart J 30:2369, 2009. Subjective and objective data that you should obtain from a patient with IE are presented in Table 37-3. Assess vital signs together with heart sounds to detect a murmur, a change in a preexisting murmur, and extra sounds (e.g., S3). TABLE 37-3 NURSING ASSESSMENT Subjective Data Important Health Information Past health history: Valvular, congenital, or syphilitic cardiac disease, including valve repair or replacement; previous endocarditis, childbirth, staphylococcal or streptococcal infections, hospital-acquired bacteremia Medications: Immunosuppressive therapy Surgery or other treatments: Recent obstetric or gynecologic procedures; invasive techniques, including catheterization, cystoscopy, intravascular procedures; recent dental or surgical procedures; GI procedures (e.g., endoscopy) Functional Health Patterns Health perception–health management: IV drug abuse, alcohol abuse; malaise Nutritional-metabolic: Weight gain or loss; anorexia; chills, diaphoresis Elimination: Bloody urine Activity-exercise: Exercise intolerance, generalized weakness, fatigue; cough, dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea; palpitations Sleep-rest: Night sweats Cognitive-perceptual: Chest, back, or abdominal pain; headache; joint tenderness, muscle tenderness Objective Data General Fever Integumentary Osler’s nodes on extremities; splinter hemorrhages under nail beds; Janeway’s lesions on palms and soles; petechiae of skin, mucous membranes, or conjunctivae; purpura; peripheral edema, finger clubbing Respiratory Tachypnea, crackles Cardiovascular Dysrhythmia, tachycardia, new murmurs, S3, S4; retinal hemorrhages Possible Diagnostic Findings Leukocytosis, anemia, ↑ ESR, ↑ CRP and cardiac enzymes; positive blood cultures; hematuria; echocardiogram showing chamber enlargement, valvular dysfunction, and vegetations; chest x-ray showing cardiomegaly and pulmonary infiltrates; ECG demonstrating ischemia and conduction defects; signs of systemic embolization or pulmonary embolism CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Nursing diagnoses for the patient with IE may include, but are not limited to, the following: • Decreased cardiac output related to altered heart rhythm, valvular insufficiency, and fluid overload • Activity intolerance related to generalized weakness, arthralgia, and alteration in oxygen transport secondary to valvular dysfunction The incidence of IE can be decreased by identifying individuals who are at risk for the disease (see Tables 37-1 and 37-2). Assessment of the patient’s history and an understanding of the disease process are crucial for planning and implementing appropriate health promotion strategies. Assessment findings are often nonspecific (see Table 37-3) but can help with the treatment plan. Fever, chronic or intermittent, is a common early sign. Instruct the patient or caregiver about the importance of monitoring body temperature. Persistent temperature elevations may mean that the drug therapy is ineffective. Patients with IE are at risk for life-threatening complications, such as stroke, pulmonary edema, and HF. Teach patients and caregivers to recognize signs and symptoms of these complications (e.g., change in mental status, dyspnea, chest pain, unexplained weight gain). Management also focuses on teaching the patient and caregiver the nature of the disease and on reducing the risk of reinfection. Explain to the patient the relationship of follow-up care, good nutrition, and early treatment of common infections (e.g., colds) to maintain health. Instruct the patient about symptoms that may indicate recurrent infection (e.g., fever, fatigue, chills). Tell the patient to notify the health care provider if any of these symptoms occur. Finally, inform the patient about the importance of prophylactic antibiotic therapy before certain invasive procedures (see Table 37-2). Pericarditis is a condition caused by inflammation of the pericardial sac (the pericardium).The pericardium is composed of the inner serous membrane (visceral pericardium) and the outer fibrous (parietal) layer (see Fig. 37-1). The pericardial space is the cavity between these two layers. Normally it contains 10 to 15 mL of serous fluid. The pericardium serves an anchoring function, provides lubrication to decrease friction during systolic and diastolic heart movements, and assists in preventing excessive dilation of the heart during diastole. It may be congenitally absent or surgically removed. Common causes of acute pericarditis are listed in Table 37-4. Most often the cause of acute pericarditis is idiopathic (unknown), with a variety of suspected viral causes. The coxsackie B virus is the most commonly identified virus.8 TABLE 37-4 Pericarditis in the patient with an MI may be described as two distinct syndromes. The first is acute pericarditis, which may occur within the initial 48 to 72 hours after an MI. The second is Dressler syndrome (late pericarditis), which appears 4 to 6 weeks after an MI (see Chapter 34). An inflammatory response is the characteristic pathologic finding in acute pericarditis. There is an influx of neutrophils, increased pericardial vascularity, and eventually fibrin deposition on the epicardium (Fig. 37-4). The patient with cardiac tamponade may report chest pain and is often confused, anxious, and restless. As the compression of the heart increases, there is decreased cardiac output (CO), muffled heart sounds, and narrowed pulse pressure. The patient develops tachypnea and tachycardia. Neck veins usually are markedly distended because of increased jugular venous pressure, and pulsus paradoxus is present. Pulsus paradoxus is a decrease in systolic BP during inspiration that is exaggerated in cardiac tamponade. (See Table 37-5 for the measurement technique.) In a patient with a slow onset of a cardiac tamponade, dyspnea may be the only clinical manifestation. The ECG is useful in the diagnosis of acute pericarditis, with changes noted in approximately 90% of the cases. The most sensitive ECG changes include diffuse (widespread) ST segment elevations. This reflects the abnormal repolarization that develops secondary to the pericardial inflammation. You need to differentiate these changes from the ST changes seen with MI. (See Chapter 36 for more information on ECG monitoring.) Echocardiographic findings are most useful in determining the presence of a pericardial effusion or cardiac tamponade. Methods such as Doppler imaging and color M-mode assess diastolic function and diagnose constrictive pericarditis (discussed later in the chapter). Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provide for visualization of the pericardium and pericardial space. Chest x-ray findings are generally normal, but cardiomegaly may be seen in a patient who has a large pericardial effusion (Fig. 37-5).

Nursing Management

Inflammatory and Structural Heart Disorders

Inflammatory Disorders of Heart

Infective Endocarditis

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Cardiac Conditions

Noncardiac Conditions

Procedure-Associated Risks

Clinical Manifestations

Diagnostic Studies

Collaborative Care

Prophylactic Treatment.

Target Groups for Prophylactic Antibiotics

People with the following heart conditions should receive prophylactic antibiotics when they have the conditions or procedures listed below.

Conditions or Procedures Requiring Antibiotic Prophylaxis

When the target groups have the following conditions or procedures, they need prophylactic antibiotics.

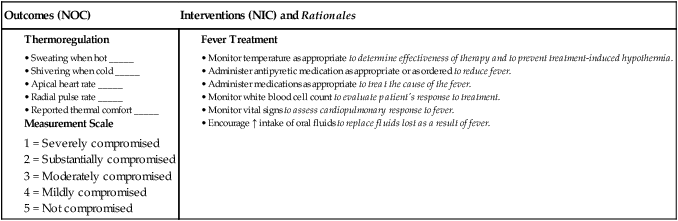

Nursing Management Infective Endocarditis

Nursing Assessment

Infective Endocarditis

Nursing Diagnoses

Nursing Implementation

Health Promotion.

Ambulatory and Home Care.

Acute Pericarditis

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Complications

Diagnostic Studies

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nursing Management: Inflammatory and Structural Heart Disorders

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access