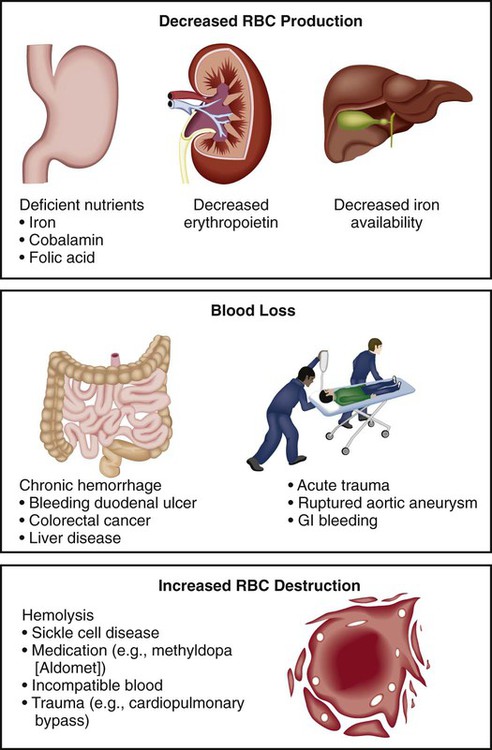

1. Describe the general clinical manifestations and complications of anemia. 2. Differentiate the etiologies, clinical manifestations, diagnostic findings, and nursing and collaborative management of iron-deficiency, megaloblastic, and aplastic anemias and anemia of chronic disease. 3. Explain the nursing management of anemia secondary to blood loss. 4. Describe the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and collaborative management of anemia caused by increased erythrocyte destruction, including sickle cell disease and acquired hemolytic anemias. 5. Describe the pathophysiology and nursing and collaborative management of polycythemia. 6. Explain the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and collaborative management of various types of thrombocytopenia. 7. Describe the types, clinical manifestations, diagnostic findings, and nursing and collaborative management of hemophilia and von Willebrand disease. 8. Explain the pathophysiology, diagnostic findings, and nursing and collaborative management of disseminated intravascular coagulation. 9. Describe the etiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and collaborative management of neutropenia. 10. Describe the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and collaborative management of myelodysplastic syndrome. 11. Compare and contrast the major types of leukemia regarding distinguishing clinical and laboratory findings. 12. Explain the nursing and collaborative management of acute and chronic leukemias. 13. Compare Hodgkin’s lymphoma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas in terms of clinical manifestations, staging, and nursing and collaborative management. 14. Describe the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and collaborative management of multiple myeloma. 15. Describe the spleen disorders and related collaborative care. 16. Describe the nursing management of the patient receiving transfusions of blood and blood components. Anemia is a deficiency in the number of erythrocytes (red blood cells [RBCs]), the quantity or quality of hemoglobin, and/or the volume of packed RBCs (hematocrit). It is a prevalent condition with many diverse causes such as blood loss, impaired production of erythrocytes, or increased destruction of erythrocytes (Fig. 31-1). Because RBCs transport oxygen (O2), erythrocyte disorders can lead to tissue hypoxia. This hypoxia accounts for many of the signs and symptoms of anemia. Anemia is not a specific disease. It is a manifestation of a pathologic process. Anemia is classified by review of the complete blood count (CBC), reticulocyte count, and peripheral blood smear. Once anemia is identified, further investigation is done to determine its specific cause.1 Anemia can result from primary hematologic problems or can develop as a secondary consequence of diseases or disorders of other body systems. The various types of anemia can be classified according to either morphology (cellular characteristic) or etiology (cause). Morphologic classification is based on erythrocyte size and color (Table 31-1). Etiologic classification is related to the clinical conditions causing the anemia2,3 (Table 31-2). Although the morphologic system is the most accurate means of classifying anemias, it is easier to discuss patient care by focusing on the etiology of the anemia. TABLE 31-1 MORPHOLOGY AND ETIOLOGY OF ANEMIA MCH, Mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCV, mean corpuscular volume. TABLE 31-2 Mild states of anemia (Hgb 10 to 12 g/dL [100 to 120 g/L]) may exist without causing symptoms. If symptoms develop, it is because the patient has an underlying disease or is experiencing a compensatory response to heavy exercise. Symptoms include palpitations, dyspnea, and mild fatigue.2,3 In severe anemia (Hgb less than 6 g/dL [60 g/L]) the patient has many clinical manifestations involving multiple body systems (Table 31-3). TABLE 31-3 Subjective and objective data that should be obtained from a patient with anemia are presented in Table 31-4. TABLE 31-4 Cobalamin (vitamin B12) and folate deficiency may occur in about 14% of older adults because of pernicious anemia, insufficient dietary intake, and malabsorption caused by low stomach acidity.4 Multiple co-morbid conditions in older adults increase the likelihood of many types of anemia occurring. Clinical manifestations of anemia in older adults may include pallor, confusion, ataxia, fatigue, worsening angina, and heart failure.2 Unfortunately, anemia may go unrecognized in older adults because these manifestations may be mistaken for normal aging changes or overlooked because of another health problem. By recognizing signs of anemia, you can play a pivotal role in health assessment and related interventions for older adults. Normally RBC production (termed erythropoiesis) is in equilibrium with RBC destruction and loss. This balance ensures that an adequate number of erythrocytes is available at all times. The normal life span of an RBC is 120 days. Three alterations in erythropoiesis may occur that decrease RBC production: (1) decreased hemoglobin synthesis may lead to iron-deficiency anemia, thalassemia, and sideroblastic anemia; (2) defective deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) synthesis in RBCs (e.g., cobalamin deficiency, folic acid deficiency) may lead to megaloblastic anemias; and (3) diminished availability of erythrocyte precursors may result in aplastic anemia and anemia of chronic disease (see Table 31-2). Iron-deficiency anemia, one of the most common chronic hematologic disorders, is found in 2% to 5% of adult men and postmenopausal women in developed countries. Those most susceptible to iron-deficiency anemia are the very young, those on poor diets, and women in their reproductive years.5,6 Normally, 1 mg of iron is lost daily through feces, sweat, and urine.7 Iron-deficiency anemia may develop as a result of inadequate dietary intake, malabsorption, blood loss, or hemolysis. (Normal iron metabolism is discussed in Chapter 30 on p. 616.) Normal dietary iron intake is usually sufficient to meet the needs of men and older women, but it may be inadequate for those individuals who have higher iron needs (e.g., menstruating or pregnant women). Table 31-5 lists nutrients needed for erythropoiesis.8,9 TABLE 31-5 NUTRITIONAL THERAPY *Supplementation rarely needed and large amounts of copper are poisonous. Malabsorption of iron may occur after certain types of gastrointestinal (GI) surgery and in malabsorption syndromes. Surgical procedures may involve removal or bypass of the duodenum (see Chapter 42). As iron absorption occurs in the duodenum, malabsorption syndromes may involve disease of the duodenum in which the absorption surface is altered or destroyed. In the early course of iron-deficiency anemia the patient may not have any symptoms. As the disease becomes chronic, any of the general manifestations of anemia may develop (see Table 31-3). In addition, specific clinical manifestations may occur related to iron-deficiency anemia. Pallor is the most common finding, and glossitis (inflammation of the tongue) is the second most common. Another finding is cheilitis (inflammation of the lips). In addition, the patient may report headache, paresthesias, and a burning sensation of the tongue, all of which are caused by lack of iron in the tissues. Laboratory abnormalities characteristic of iron-deficiency anemia are presented in Table 31-6. Other diagnostic studies (e.g., stool guaiac test) are done to determine the cause of the iron deficiency. Endoscopy and colonoscopy may be used to detect GI bleeding. A bone marrow biopsy may be done if other tests are inconclusive. TABLE 31-6 LABORATORY STUDY FINDINGS IN ANEMIAS MCV, Mean corpuscular volume; N, normal; TIBC, total iron-binding capacity. The main goal is to treat the underlying disease that is causing reduced intake (e.g., malnutrition, alcoholism) or absorption of iron. In addition, efforts are directed toward replacing iron (Table 31-7). Teach the patient which foods are good sources of iron (see Table 31-5). If nutrition is already adequate, increasing iron intake by dietary means may not be practical. Consequently, oral or occasionally parenteral iron supplements are used. If the iron deficiency is from acute blood loss, the patient may require a transfusion of packed RBCs. TABLE 31-7 COLLABORATIVE CARE

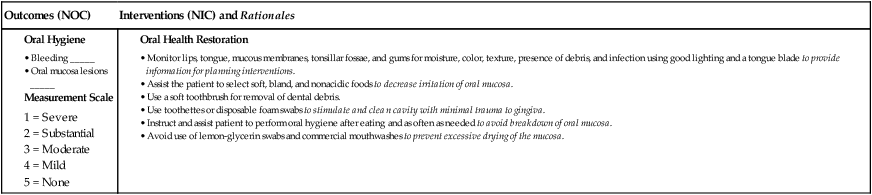

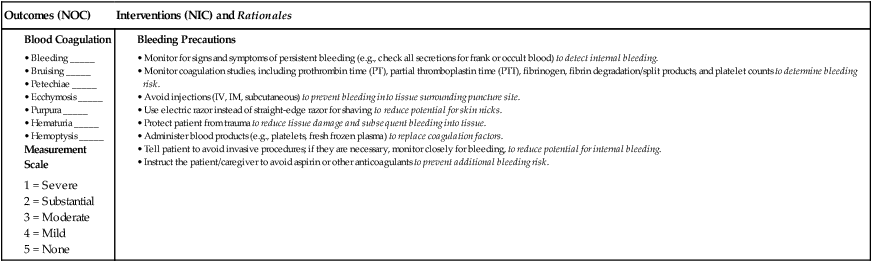

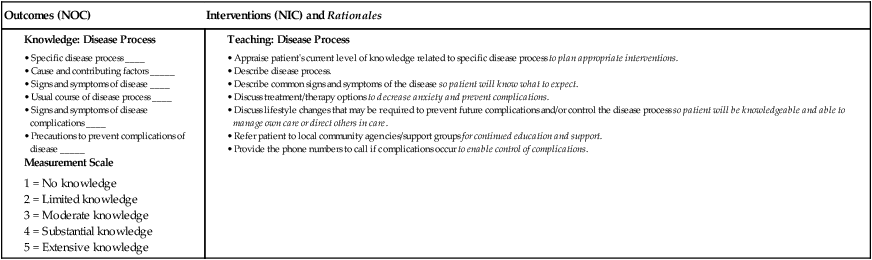

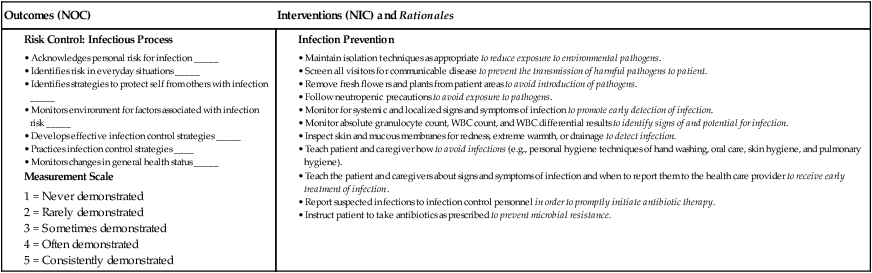

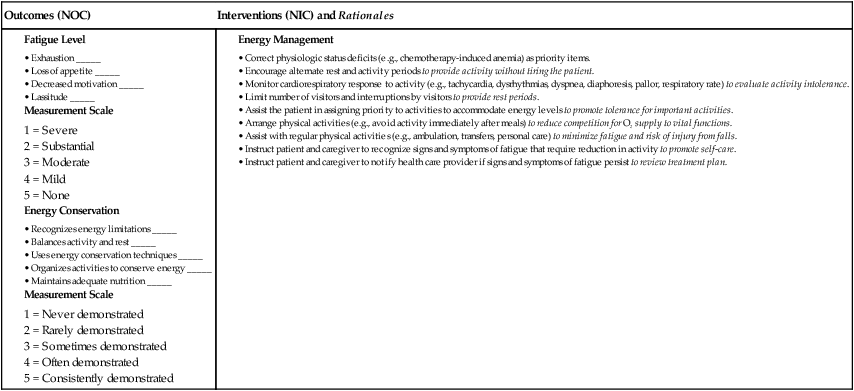

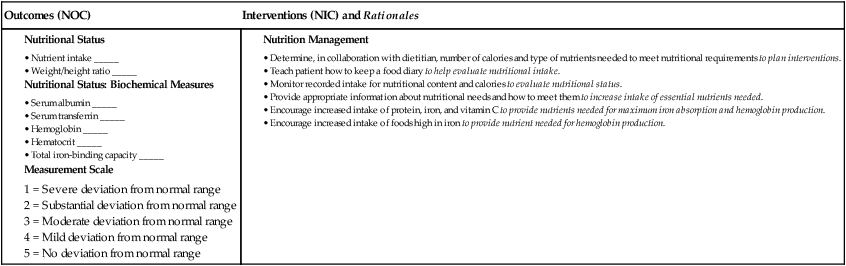

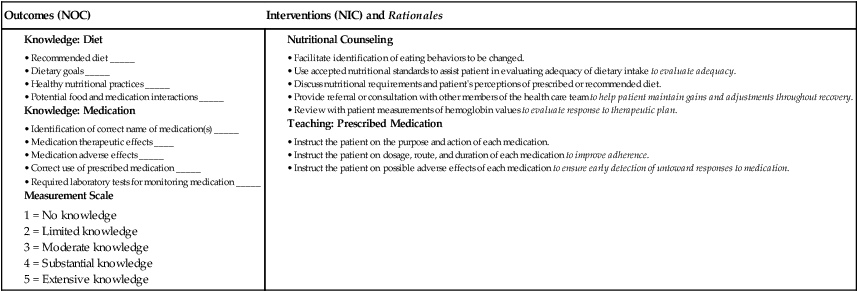

Nursing Management

Hematologic Problems

Anemia

Definition and Classification

Morphology

Etiology

Normocytic, normochromic (normal size and color)

MCV 80-100 fL, MCH 27-34 pg

Acute blood loss, hemolysis, chronic kidney disease, chronic disease, cancers, sideroblastic anemia, endocrine disorders, starvation, aplastic anemia, sickle cell anemia, pregnancy

Microcytic, hypochromic (small size, pale color)

MCV <80 fL, MCH <27 pg

Iron-deficiency anemia, vitamin B6 deficiency, copper deficiency, thalassemia, lead poisoning

Macrocytic (megaloblastic), normochromic (large size, normal color)

MCV >100 fL, MCH >34 pg

Cobalamin (vitamin B12) deficiency, folic acid deficiency, liver disease (including effects of alcohol abuse), postsplenectomy

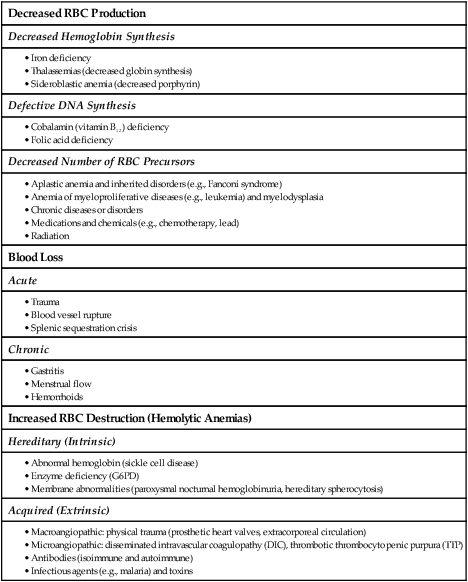

Decreased RBC Production

Decreased Hemoglobin Synthesis

Defective DNA Synthesis

Decreased Number of RBC Precursors

Blood Loss

Acute

Chronic

Increased RBC Destruction (Hemolytic Anemias)

Hereditary (Intrinsic)

Acquired (Extrinsic)

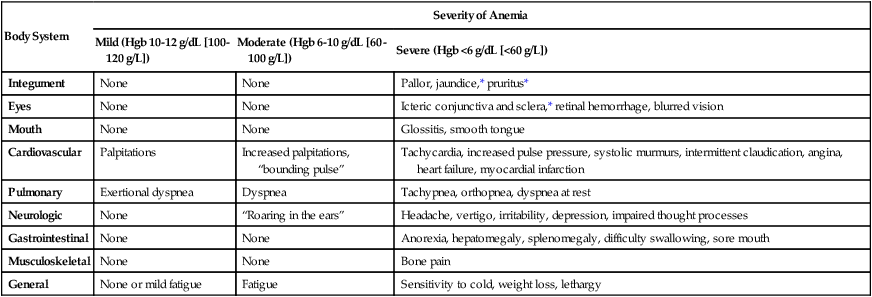

Clinical Manifestations

Body System

Severity of Anemia

Mild (Hgb 10-12 g/dL [100-120 g/L])

Moderate (Hgb 6-10 g/dL [60-100 g/L])

Severe (Hgb <6 g/dL [<60 g/L])

Integument

None

None

Pallor, jaundice,* pruritus*

Eyes

None

None

Icteric conjunctiva and sclera,* retinal hemorrhage, blurred vision

Mouth

None

None

Glossitis, smooth tongue

Cardiovascular

Palpitations

Increased palpitations, “bounding pulse”

Tachycardia, increased pulse pressure, systolic murmurs, intermittent claudication, angina, heart failure, myocardial infarction

Pulmonary

Exertional dyspnea

Dyspnea

Tachypnea, orthopnea, dyspnea at rest

Neurologic

None

“Roaring in the ears”

Headache, vertigo, irritability, depression, impaired thought processes

Gastrointestinal

None

None

Anorexia, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, difficulty swallowing, sore mouth

Musculoskeletal

None

None

Bone pain

General

None or mild fatigue

Fatigue

Sensitivity to cold, weight loss, lethargy

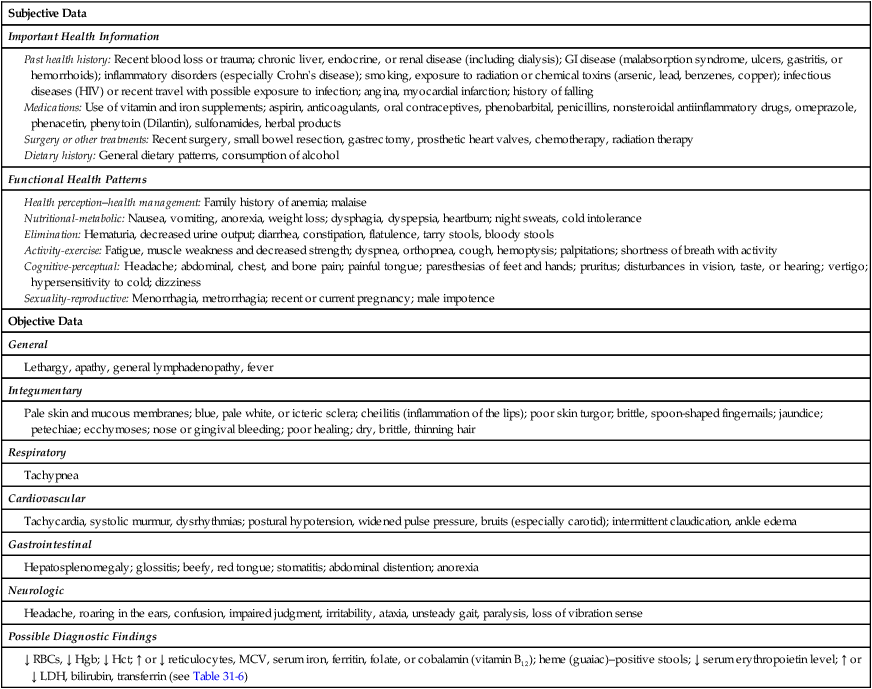

Nursing Management Anemia

Nursing Assessment

Gerontologic Considerations

Anemia

Anemia Caused by Decreased Erythrocyte Production

Iron-Deficiency Anemia

Etiology

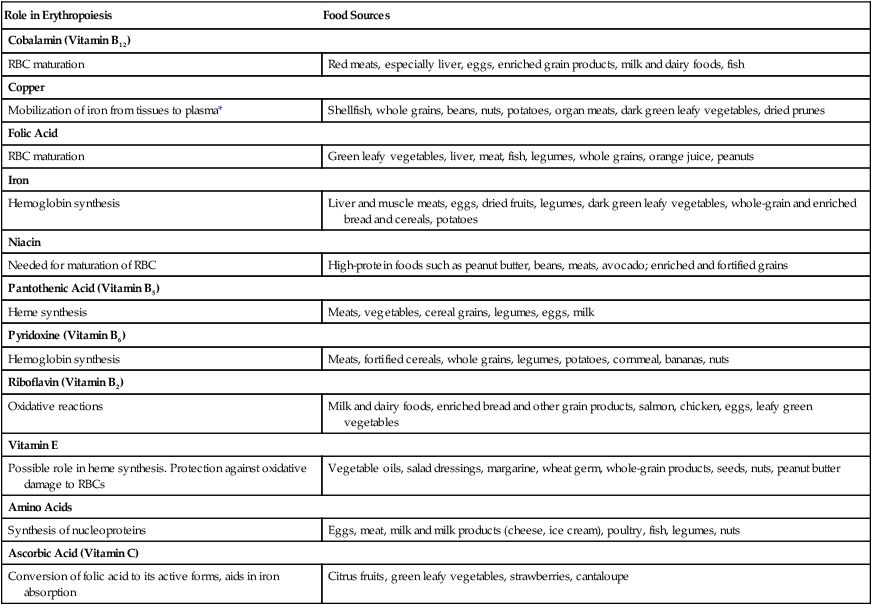

Nutrients for Erythropoiesis

Role in Erythropoiesis

Food Sources

Cobalamin (Vitamin B12)

RBC maturation

Red meats, especially liver, eggs, enriched grain products, milk and dairy foods, fish

Copper

Mobilization of iron from tissues to plasma*

Shellfish, whole grains, beans, nuts, potatoes, organ meats, dark green leafy vegetables, dried prunes

Folic Acid

RBC maturation

Green leafy vegetables, liver, meat, fish, legumes, whole grains, orange juice, peanuts

Iron

Hemoglobin synthesis

Liver and muscle meats, eggs, dried fruits, legumes, dark green leafy vegetables, whole-grain and enriched bread and cereals, potatoes

Niacin

Needed for maturation of RBC

High-protein foods such as peanut butter, beans, meats, avocado; enriched and fortified grains

Pantothenic Acid (Vitamin B5)

Heme synthesis

Meats, vegetables, cereal grains, legumes, eggs, milk

Pyridoxine (Vitamin B6)

Hemoglobin synthesis

Meats, fortified cereals, whole grains, legumes, potatoes, cornmeal, bananas, nuts

Riboflavin (Vitamin B2)

Oxidative reactions

Milk and dairy foods, enriched bread and other grain products, salmon, chicken, eggs, leafy green vegetables

Vitamin E

Possible role in heme synthesis. Protection against oxidative damage to RBCs

Vegetable oils, salad dressings, margarine, wheat germ, whole-grain products, seeds, nuts, peanut butter

Amino Acids

Synthesis of nucleoproteins

Eggs, meat, milk and milk products (cheese, ice cream), poultry, fish, legumes, nuts

Ascorbic Acid (Vitamin C)

Conversion of folic acid to its active forms, aids in iron absorption

Citrus fruits, green leafy vegetables, strawberries, cantaloupe

Clinical Manifestations

Diagnostic Studies

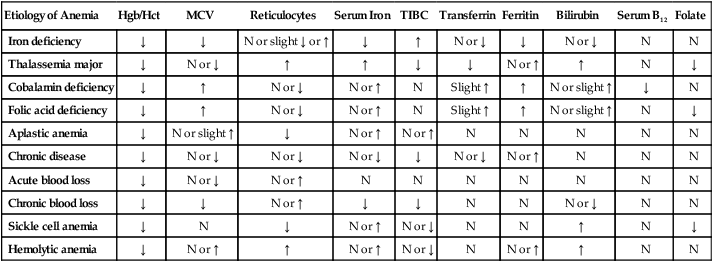

Etiology of Anemia

Hgb/Hct

MCV

Reticulocytes

Serum Iron

TIBC

Transferrin

Ferritin

Bilirubin

Serum B12

Folate

Iron deficiency

↓

↓

N or slight ↓ or ↑

↓

↑

N or ↓

↓

N or ↓

N

N

Thalassemia major

↓

N or ↓

↑

↑

↓

↓

N or ↑

↑

N

↓

Cobalamin deficiency

↓

↑

N or ↓

N or ↑

N

Slight ↑

↑

N or slight ↑

↓

N

Folic acid deficiency

↓

↑

N or ↓

N or ↑

N

Slight ↑

↑

N or slight ↑

N

↓

Aplastic anemia

↓

N or slight ↑

↓

N or ↑

N or ↑

N

N

N

N

N

Chronic disease

↓

N or ↓

N or ↓

N or ↓

↓

N or ↓

N or ↑

N

N

N

Acute blood loss

↓

N or ↓

N or ↑

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

Chronic blood loss

↓

↓

N or ↑

↓

↓

N

N

N or ↓

N

N

Sickle cell anemia

↓

N

↓

N or ↑

N or ↓

N

N

↑

N

↓

Hemolytic anemia

↓

N or ↑

↑

N or ↑

N or ↓

N

N or ↑

↑

N

N

Collaborative Care

Iron-Deficiency Anemia