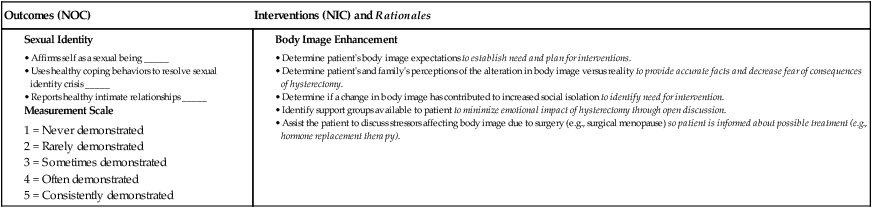

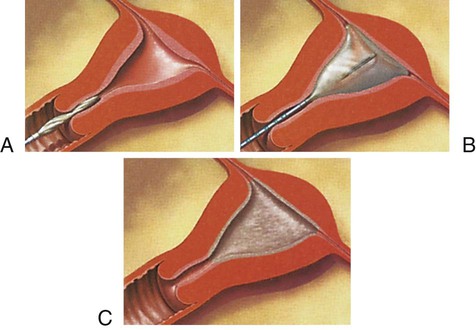

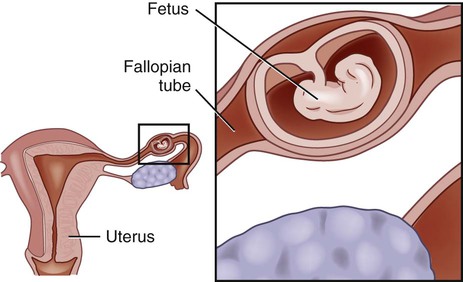

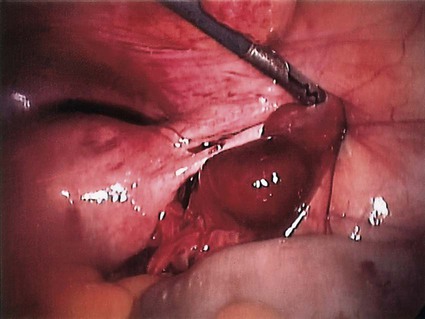

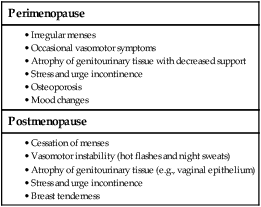

Nancy MacMullen and Laura Dulski 1. Summarize the etiologies of infertility and the strategies for diagnosis and treatment of the infertile woman. 2. Describe the etiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and collaborative management of menstrual problems and abnormal vaginal bleeding. 3. Identify the risk factors, clinical manifestations, and collaborative care of ectopic pregnancy. 4. Describe the changes related to menopause and the nursing and collaborative management of the patient with menopausal symptoms. 5. Differentiate among the common problems that affect the vulva, vagina, and cervix and the related nursing and collaborative management. 6. Describe the assessment, collaborative care, and nursing management of women with pelvic inflammatory disease and endometriosis. 7. Explain the clinical manifestations, diagnostic studies, collaborative care, and surgical therapy for cervical, endometrial, ovarian, and vulvar cancers. 8. Summarize the preoperative and postoperative nursing management for the patient requiring surgery of the female reproductive system. 9. Differentiate among the common problems that occur with cystoceles, rectoceles, and fistulas and the related nursing and collaborative management. 10. Summarize the clinical manifestations of sexual assault and the appropriate nursing and collaborative management of the patient who has been sexually assaulted. Infertility is the inability to conceive after at least 1 year of regular unprotected intercourse.1 Approximately 15% of couples in North America are infertile. Understandably, infertility can be both a physical and an emotional crisis. Infertility may be caused by either female or male or combined factors. (Conditions that cause male infertility are discussed in Chapter 55.) In some cases, the cause of infertility may not be identified. The factors usually causing female infertility include problems with ovulation (anovulation or inadequate corpus luteum), tubal obstruction or dysfunction (endometriosis or damage from pelvic infection), and uterine or cervical factors (fibroid tumors or structural anomalies). Risk factors for infertility include tobacco and illicit drug use and being obese or thin. In women the risk for infertility starts about age 30 and increases after age 40.2 A detailed history and a general physical examination of the woman and her partner provide the basis for selecting diagnostic studies (Table 54-1). The possibility of medical, genetic, or gynecologic diseases is explored before tests are performed to determine problems affecting general health and fertility. These tests include hormone levels, ovulatory studies, tubal patency studies, and postcoital studies. Other screening tests for infertility include semen analysis and pelvic ultrasound. TABLE 54-1 The management of infertility problems depends on the cause. If infertility is secondary to an alteration in ovarian function, supplemental hormone therapy to restore and maintain ovulation may be used. Drug therapy to treat infertility is presented in Table 54-2. Chronic cervicitis and inadequate estrogenic stimulation are cervical factors causing infertility. Antibiotic therapy is indicated for cervicitis. Inadequate estrogenic stimulation is treated using estrogen. TABLE 54-2 FSH, Follicle-stimulating hormone; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone. When a couple has not succeeded in conceiving while under infertility management, an option is intrauterine insemination with sperm from the partner or a donor. If this technique does not succeed, assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) may be used. ARTs include in vitro fertilization (IVF), gamete intrafallopian transfer (GIFT), zygote intrafallopian transfer (ZIFT), donor gametes, and embryo cryopreservation. IVF is the removal of mature oocytes from the woman’s ovarian follicle via laparoscopy, followed by in vitro fertilization of the ova with the partner’s sperm. When fertilization and cleavage have occurred, the resulting embryos are transferred into the woman’s uterus. The procedure requires 2 to 3 days to complete and is used in cases of fallopian tube obstruction, diminished sperm count, and unexplained infertility. Frequently, multiple attempts are needed for successful implantation. IVF is financially costly and emotionally stressful.3 Treatment to prevent a possible spontaneous abortion is limited. Although bed rest and avoidance of vaginal intercourse are often recommended, there is no evidence that these measures improve the outcome. The woman is advised to report any bleeding to her health care provider. Most women proceed to abortion regardless of treatment. If the products of conception do not pass completely or bleeding becomes excessive, a dilation and curettage (D&C) procedure is generally performed.4 The D&C involves dilating the cervix and scraping the endometrium of the uterus to empty the contents of the uterus. Induced abortion is an intentional or elective termination of a pregnancy. Induced abortion is done for personal reasons (at the request of the woman) and for medical reasons. Several techniques are used to induce abortion, including menstrual extraction, suction curettage, dilation and evacuation (D&E), and drug therapy (Table 54-3). Deciding on which technique to use to terminate a pregnancy depends on the gestational age (length of the pregnancy) and the woman’s condition. Suction curettage may be performed up to 14 weeks of gestation and accounts for more than 90% of abortion procedures. TABLE 54-3 The normal menstrual cycle is discussed in Chapter 51. The hormonal changes related to the menstrual cycle are shown in Fig. 51-7. Menstruation may be irregular during the first few years after menarche and the years preceding menopause. Once established, a woman’s menstrual cycles usually have a predictable pattern. However, considerable normal variation exists among women in cycle length and in duration, amount, and character of the menstrual flow (see Table 51-2). Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is a symptom complex related to the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. The symptoms can be severe enough to impair interpersonal relationships or interfere with usual activities. Because many symptoms may be associated with PMS, it is difficult to define. However, PMS symptoms always occur cyclically during the luteal phase before the onset of menstruation and are not present at other times of the month. About 40% of all women have been significantly affected by PMS during their lifetime.5 Nondrug and drug strategies can relieve some PMS symptoms (Table 54-4). However, no single treatment is available. The goal of treatment is to reduce the severity of symptoms and enhance the woman’s sense of control and quality of life. Dysmenorrhea is abdominal cramping pain or discomfort associated with menstrual flow. The degree of pain and discomfort varies with the individual. The two types of dysmenorrhea are primary (no pathologic condition exists) and secondary (pelvic disease is the underlying cause).5 Dysmenorrhea is one of the most common gynecologic problems. Oral contraceptives may also be used. They decrease dysmenorrhea by reducing endometrial hyperplasia. Acupuncture and transcutaneous nerve stimulation may be used for women who have inadequate relief from medications or who prefer not to take medications. Patients who are unresponsive to these treatments should be evaluated for chronic pelvic pain (discussed later in this chapter on p. 1289). Anovulation is the most common reason for missing menses once pregnancy has been ruled out. Additional causes of amenorrhea are listed in Table 54-5. Primary amenorrhea refers to the failure of menstrual cycles to begin by age 16 years or by age 14 years if secondary sex characteristics are present. Secondary amenorrhea refers to the cessation of menstrual cycles once they had been established. TABLE 54-5 The excessive bleeding associated with menorrhagia can be characterized as an increased duration (more than 7 days), increased amount (more than 80 mL), or both. Anovulatory uterine bleeding is the most common cause of menorrhagia. An unopposed estrogen state continues to build up the endometrium until it becomes unstable, resulting in menorrhagia. For young women with excessive bleeding, clotting disorders must be considered. Uterine fibroids (also called leiomyomas) and endometrial polyps are common causes of menorrhagia for women in their childbearing years.6 Balloon thermotherapy is a technique for menorrhagia that involves the introduction of a soft, flexible balloon into the uterus. The balloon is then inflated with sterile fluid (Fig. 54-1). The fluid in the balloon is heated and maintained for 8 minutes, thus causing ablation (removal) of the uterine lining. When the treatment is completed, the fluid is withdrawn from the balloon and the catheter is removed from the uterus. The uterine lining sloughs off in the next 7 to 10 days. Uterine balloon thermotherapy is contraindicated for women who desire to maintain their fertility and for women with any suspected uterine abnormalities such as fibroids, suspected endometrial cancer, prior cesarean delivery, or myomectomy. With severe bleeding, hospitalization is indicated. All patients with menorrhagia should be evaluated for anemia and treated as indicated. Teaching women about the characteristics of the menstrual cycle will enable them to identify normal variations. Table 51-2 includes characteristics of the menstrual cycle and related patient teaching. This knowledge can decrease apprehension and dispel misconceptions about the menstrual cycle. If the patient’s menstrual cycle pattern does not fall within the normal range, urge her to discuss this with her health care provider. The selection of internal or external sanitary protection is a matter of personal preference. Tampons are convenient and make menstrual hygiene easier, whereas pads may provide better protection. Using a combination of tampons and pads and avoiding prolonged use of superabsorbent tampons may decrease the risk of toxic shock syndrome (TSS). TSS is an acute life-threatening condition caused by a toxin from Staphylococcus aureus. TSS causes high fever, vomiting, diarrhea, weakness, myalgia, and a sunburn-like rash.7 An ectopic pregnancy is the implantation of the fertilized ovum anywhere outside the uterine cavity. Approximately 3% of all pregnancies are ectopic, and approximately 98% of these occur in the fallopian tube8 (Fig. 54-2). The remaining 2% to 3% may be ovarian, abdominal, or cervical. Ectopic pregnancy is a life-threatening condition. Earlier identification has contributed to decreased mortality rates. Ectopic pregnancy can be a diagnostic challenge because of its similarity to other pelvic and abdominal disorders, such as salpingitis, spontaneous abortion, ruptured ovarian cyst, appendicitis, and peritonitis. A serum (radioimmunoassay) pregnancy test should be performed. If the test is negative, an ectopic pregnancy is not likely. If ectopic pregnancy cannot be excluded by the pregnancy test, further evaluation is warranted. If the patient is in stable condition, a combination of serial measurements of serum β-hCG and vaginal ultrasonography is used.9 Absence of a normal intrauterine pregnancy means that the diagnosis is probably a spontaneous abortion or an ectopic pregnancy. With a spontaneous abortion, serial serum β-hCG levels will decrease over time. A complete blood count is obtained when there is any concern regarding the amount of blood loss or if surgery is contemplated. Surgery remains the primary approach for treating ectopic pregnancies and should be performed immediately. However, medical management with methotrexate (Folex) is being used with increasing success in patients who are hemodynamically stable and have a mass less than 3 cm in size.10 A conservative surgical approach limits damage to the reproductive system as much as possible. Removal of the fetus from the tube is preferred to removing the tube. Laparoscopy is preferable to laparotomy because it decreases blood loss and the length of the hospital stay (Fig. 54-3). If the tube ruptures, conservative surgical approaches may not be possible. The patient may need a blood transfusion and supplemental IV fluid therapy to relieve shock and restore a satisfactory blood volume for safe anesthesia and surgery. The use of laparoscopy has resulted in fewer repeated ectopic pregnancies and a higher rate of future successful pregnancies. Perimenopause is a normal life transition that begins with the first signs of change in menstrual cycles and ends after cessation of menses.11 Menopause is the physiologic cessation of menses associated with declining ovarian function. It is usually considered complete after 1 year of amenorrhea (absence of menstruation). Menopause starts gradually and is usually associated with changes in menstruation, including menstrual flows that are increased, decreased, or irregular. Eventually complete cessation of menses occurs. Postmenopause is a term that refers to the time in a woman’s life after menopause. Clinical manifestations of perimenopause and postmenopause are presented in Table 54-6. Perimenopause is a time of erratic hormonal fluctuation. Irregular vaginal bleeding is common. With decreasing estrogen, hot flashes and other symptoms begin. The signs and symptoms of diminished estrogen are listed in Table 54-7. The loss of estrogen plays a significant role in the cause of age-related alterations. Changes most critical to a woman’s well-being are the increased risks for coronary artery disease (CAD) and osteoporosis (secondary to bone density loss). Other changes include a redistribution of fat, a tendency to gain weight more easily, muscle and joint pain, loss of skin elasticity, changes in hair amount and distribution, and atrophy of external genitalia and breast tissue. TABLE 54-7 MANIFESTATIONS OF ESTROGEN DEFICIENCY Hallmarks of perimenopause include vasomotor instability (hot flashes) and irregular menses. A hot flash (occurs in up to 80% of all women) is described as a sudden sensation of intense heat along with perspiration and flushing.12 These sensations may last from several seconds to 5 minutes and occur most often at night, thereby disturbing sleep. The cause of hot flashes, or vasomotor instability, is not clearly understood. It has been theorized that temperature regulators in the brain are in proximity to the area where gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is released. The lowered estrogen levels are correlated with dilation of cutaneous blood vessels, resulting in hot flashes and increased sweating. The more sudden the withdrawal of estrogen (e.g., surgical removal of the ovaries), the more likely the symptoms will be severe if no hormone replacement is provided. Symptoms usually subside over time and typically last from 5 to 10 years with or without treatment.13 Hot flashes can be triggered by stress and situations that affect body temperature, such as eating a hot meal, hot weather, or warm clothing. Women who smoke are at higher risk for hot flashes because smoking affects estrogen metabolism. African American women report the highest incidence of hot flashes, whereas Asian American women report the lowest number.13 Hormone therapy (HT) was once standard therapy in the United States for treating menopausal symptoms. HT includes estrogen for women without a uterus or estrogen and progesterone for women with a uterus. Findings from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) clinical trials changed this practice.14 The data showed that women who had taken estrogen plus progestin (Prempro) had an increased risk of breast cancer, stroke, heart disease, and emboli. However, these women had fewer hip fractures and a lower risk of developing colorectal cancer. Women who took only estrogen (Premarin) had an increased risk of stroke and emboli. However, these women had decreased risk for fractures with no increased risk for heart disease or breast or colorectal cancer. A recent systematic review has updated and validated the results of the WHI trials.15 Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), such as raloxifene (Evista), are also used to treat menopausal problems. These drugs have some of the positive benefits of estrogen, such as preventing bone loss, without the negative effects such as endometrial hyperplasia. Raloxifene competes with estrogen for estrogen receptor sites.16 It decreases bone loss and serum cholesterol with minimal effects on breast and uterine tissue. Bisphosphonates, including alendronate (Fosamax) and risedronate (Actonel), are also used to decrease the risk for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. These drugs enhance bone mineral density by suppressing resorption. SERMs and bisphosphonates are discussed further in Chapter 64 with respect to their role in the management of osteoporosis. Good nutrition can decrease the risk of cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis in addition to assisting with vasomotor symptoms. A daily intake of about 30 cal/kg of body weight is recommended. A decrease in metabolic rate and careless eating habits can cause the weight gain and fatigue often attributed to menopause. An adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D helps maintain healthy bones and counteracts loss of bone density. Postmenopausal women not receiving supplemental estrogen should have a daily calcium intake of at least 1500 mg, whereas those taking estrogen replacement need at least 1000 mg/day. Calcium supplements are best absorbed when taken with meals. Either dietary calcium or calcium supplements may be used (see Tables 64-14 and 64-15). The diet should be high in complex carbohydrates and vitamin B complex, especially B6. Phytoestrogens (soy, tofu, chickpeas, sunflower seeds) have been used to reduce menopausal symptoms. Herbal remedies, such as black cohosh, have become popular in treating menopausal symptoms (see Complementary & Alternative Therapies box above). Consultation with an experienced herbal practitioner is recommended before initiating therapy.

Nursing Management

Female Reproductive Problems

Infertility

Etiology and Pathophysiology

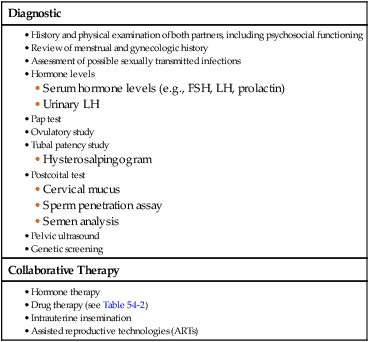

Diagnostic Studies

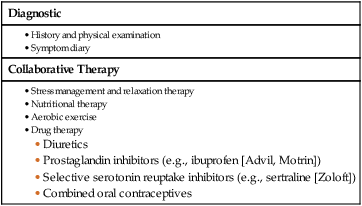

Diagnostic

Collaborative Therapy

Nursing and Collaborative Management Infertility

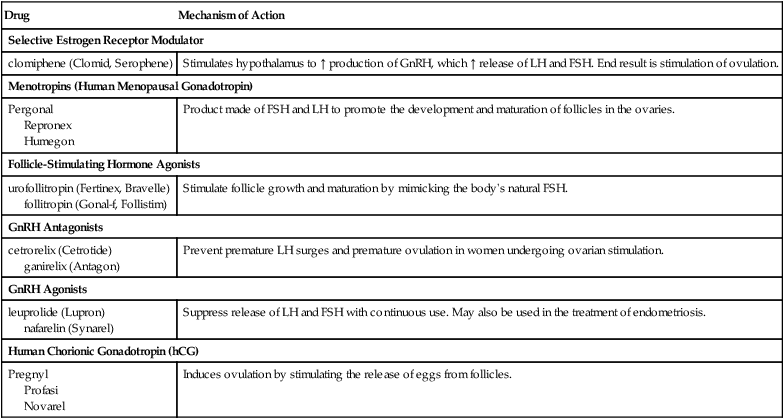

Drug

Mechanism of Action

Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator

clomiphene (Clomid, Serophene)

Stimulates hypothalamus to ↑ production of GnRH, which ↑ release of LH and FSH. End result is stimulation of ovulation.

Menotropins (Human Menopausal Gonadotropin)

Pergonal

Repronex

Humegon

Product made of FSH and LH to promote the development and maturation of follicles in the ovaries.

Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Agonists

urofollitropin (Fertinex, Bravelle)

follitropin (Gonal-f, Follistim)

Stimulate follicle growth and maturation by mimicking the body’s natural FSH.

GnRH Antagonists

cetrorelix (Cetrotide)

ganirelix (Antagon)

Prevent premature LH surges and premature ovulation in women undergoing ovarian stimulation.

GnRH Agonists

leuprolide (Lupron)

nafarelin (Synarel)

Suppress release of LH and FSH with continuous use. May also be used in the treatment of endometriosis.

Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG)

Pregnyl

Profasi

Novarel

Induces ovulation by stimulating the release of eggs from follicles.

Abortion

Spontaneous Abortion

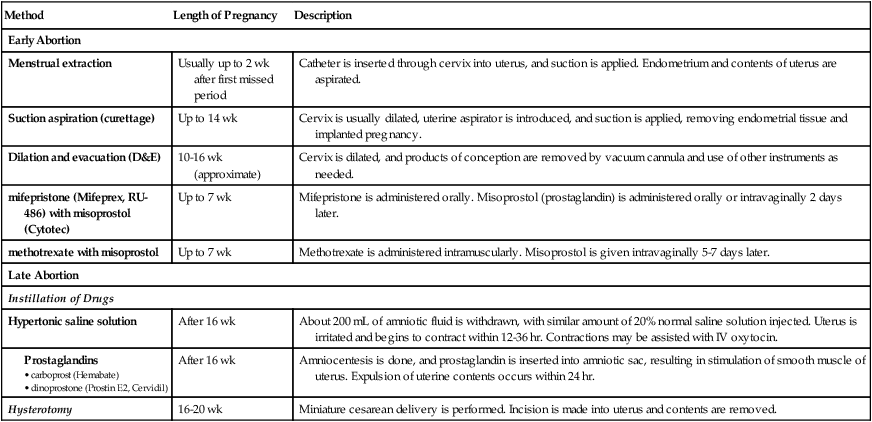

Induced Abortion

Method

Length of Pregnancy

Description

Early Abortion

Menstrual extraction

Usually up to 2 wk after first missed period

Catheter is inserted through cervix into uterus, and suction is applied. Endometrium and contents of uterus are aspirated.

Suction aspiration (curettage)

Up to 14 wk

Cervix is usually dilated, uterine aspirator is introduced, and suction is applied, removing endometrial tissue and implanted pregnancy.

Dilation and evacuation (D&E)

10-16 wk (approximate)

Cervix is dilated, and products of conception are removed by vacuum cannula and use of other instruments as needed.

mifepristone (Mifeprex, RU-486) with misoprostol (Cytotec)

Up to 7 wk

Mifepristone is administered orally. Misoprostol (prostaglandin) is administered orally or intravaginally 2 days later.

methotrexate with misoprostol

Up to 7 wk

Methotrexate is administered intramuscularly. Misoprostol is given intravaginally 5-7 days later.

Late Abortion

Instillation of Drugs

Hypertonic saline solution

After 16 wk

About 200 mL of amniotic fluid is withdrawn, with similar amount of 20% normal saline solution injected. Uterus is irritated and begins to contract within 12-36 hr. Contractions may be assisted with IV oxytocin.

After 16 wk

Amniocentesis is done, and prostaglandin is inserted into amniotic sac, resulting in stimulation of smooth muscle of uterus. Expulsion of uterine contents occurs within 24 hr.

Hysterotomy

16-20 wk

Miniature cesarean delivery is performed. Incision is made into uterus and contents are removed.

Problems Related to Menstruation

Premenstrual Syndrome

Diagnostic Studies and Collaborative Care

Dysmenorrhea

Nursing and Collaborative Management Dysmenorrhea

Abnormal Vaginal Bleeding

Types of Irregular Bleeding

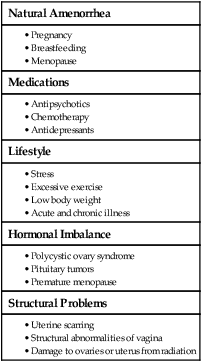

Oligomenorrhea and Amenorrhea.

Natural Amenorrhea

Medications

Lifestyle

Hormonal Imbalance

Structural Problems

Menorrhagia.

Diagnostic Studies and Collaborative Care

Nursing Management Abnormal Vaginal Bleeding

Ectopic Pregnancy

Diagnostic Studies

Nursing and Collaborative Management Ectopic Pregnancy

Perimenopause and Postmenopause

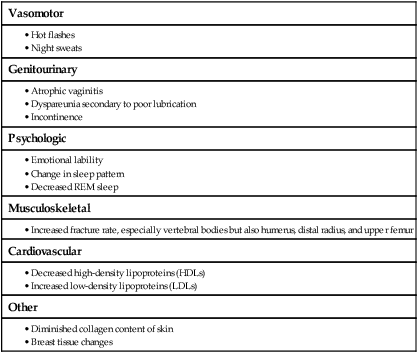

Clinical Manifestations

Vasomotor

Genitourinary

Psychologic

Musculoskeletal

Cardiovascular

Other

Collaborative Care

Drug Therapy.

Nutritional Therapy.