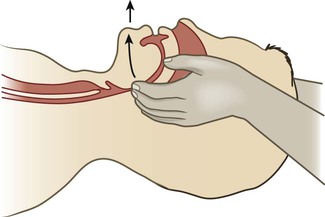

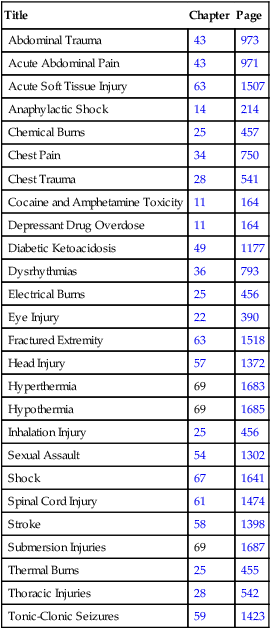

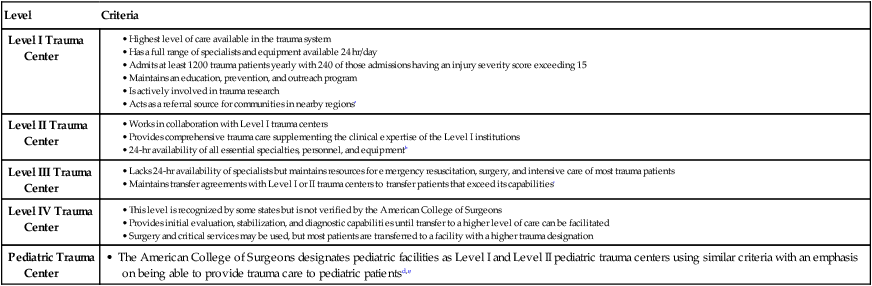

Chapter 69 One of the tests of leadership is the ability to recognize a problem before it becomes an emergency. 1. Apply the steps in triage, the primary survey, and the secondary survey to a patient experiencing a medical, surgical, or traumatic emergency. 2. Relate the pathophysiology to the assessment and collaborative care of select environmental emergencies (e.g., hyperthermia, hypothermia, submersion injury, bites). 3. Relate the pathophysiology to the assessment and collaborative care of select toxicologic emergencies. 4. Select appropriate nursing interventions for victims of violence. 5. Differentiate among the responsibilities of health care providers, the community, and select federal agencies in emergency and mass casualty incident preparedness. The emergency management of various medical, surgical, and traumatic emergencies is discussed throughout the textbook. Tables summarize emergency management of specific problems. Table 69-1 lists each emergency management table by title, chapter number, and page. EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT Most patients with life-threatening or potentially life-threatening problems arrive at the hospital through the emergency department (ED). More patients report to the ED for less urgent conditions. Every year more than 136 million people visit EDs. This number is increasing for a variety of reasons, including (1) the inability to see a primary care provider, (2) an aging population, (3) shorter hospital stays resulting in frequent readmissions, (4) acute mental health crises, and (5) lack of health insurance (or a primary care provider). These factors, plus the increase in ED closures, result in chronic overcrowding and long wait times.1,2 eTABLE 69-1 aAmerican College of Surgeons. (2010, April 22). Level I requirements by chapter. Retrieved from www.facs.org/trauma/vrc1.pdf. bAmerican College of Surgeons. (2010, April 22). Level II requirements by chapter. Retrieved from www.facs.org/trauma/vrc2.pdf. cAmerican College of Surgeons. (2010, April 22). Level III requirements by chapter. Retrieved from www.facs.org/trauma/vrc3.pdf. dAmerican College of Surgeons. (2010, April 22). Level I pediatric requirements by chapter. Retrieved from www.facs.org/trauma/vrcped1.pdf. eAmerican College of Surgeons. (2010, April 22). Level II pediatric requirements by chapter. Retrieved from www.facs.org/trauma/vrcped2.pdf. From Hammond BB, Zimmerman PG, eds: Sheehy’s manual of emergency care, ed 7, St Louis, 2013, Mosby. eTABLE 69-2 Emergency nurses care for patients of all ages and with a variety of problems. However, some EDs specialize in certain patient populations or conditions, such as pediatric ED or trauma ED. (See eTable 69-1 for the resources at various levels of trauma designated facilities.) The Emergency Nurses Association (ENA) is the specialty organization aimed at advancing emergency nursing practice. The ENA provides standards of care for nurses working in the ED, and a certification process that allows nurses to become certified emergency nurses (CENs).3 Triage, a French word meaning “to sort,” refers to the process of rapidly determining patient acuity. It is one of the most important assessment skills needed by emergency nurses.4,5 Most often, you will confront multiple patients who have a variety of problems. The triage process works on the premise that patients who have a threat to life must be treated before other patients. A triage system identifies and categorizes patients so that the most critical are treated first. The ENA and American College of Emergency Physicians support the use of a five-level triage system.6 The Emergency Severity Index (ESI) is a five-level triage system that incorporates concepts of illness severity and resource utilization (e.g., electrocardiogram [ECG], laboratory work, radiology studies, IV fluids) to determine who should be treated first5 (Table 69-2). The ESI includes a triage algorithm that directs you to assign an ESI level to patients coming into the ED. (The triage algorithm can be found in the ESI Implementation Handbook available at www.ahrq.gov/research/esi.) Initially, assess the patient for any threats to life (ESI-1) (e.g., Is the patient dying?) or presence of a high-risk situation (ESI-2) (e.g., Is this a high-risk patient who should not wait to be seen?). Next, evaluate patients who do not meet the criteria for ESI-1 or ESI-2 for the number of anticipated resources they may need. Assign patients to ESI level 3, 4, or 5 based on this determination. Normal vital signs are required for patients assigned to ESI level 3. Patients with abnormal vital signs may be reassigned to ESI level 2.5 (For practice using the ESI triage system, see the ESI Implementation Handbook available at www.ahrq.gov/research/esi.) TABLE 69-2 FIVE-LEVEL EMERGENCY SEVERITY INDEX (ESI) ABCs, Airway, breathing, circulation. Modified and reprinted with permission. Copyright 1999, Richard C. Wuerz, MD, and David R. Eitel, MD. After you complete the initial focused assessment to determine the presence of actual or potential threats to life, proceed with a more detailed assessment. A systematic approach to this assessment decreases the time needed to identify potential threats to life and limits the risk of overlooking a life-threatening condition. A primary and secondary survey is the approach used for all trauma patients. For nontrauma patients, the primary survey is followed by a focused assessment. (Focused assessments are discussed in Chapter 3.) The primary survey (Table 69-3) focuses on airway, breathing, circulation (ABC), disability, and exposure or environmental control. It aims to identify life-threatening conditions so that appropriate interventions can be started. You may identify life-threatening conditions related to ABCs (Table 69-4) at any point during the primary survey. When this occurs, start interventions immediately, before moving to the next step of the survey. TABLE 69-3 EMERGENCY ASSESSMENT: PRIMARY SURVEY AVPU, A = alert, V = responsive to voice, P = responsive to pain, and U = unresponsive. TABLE 69-4 POTENTIAL LIFE-THREATENING CONDITIONS FOUND DURING PRIMARY SURVEY* Primary signs and symptoms in a patient with a compromised airway include dyspnea, inability to speak, gasping (agonal) breaths, foreign body in the airway, and trauma to the face or neck. Airway maintenance should progress rapidly from the least to the most invasive method. Treatment includes opening the airway using the jaw-thrust maneuver (avoiding hyperextension of the neck) (Fig. 69-1), suctioning and/or removal of foreign body, insertion of a nasopharyngeal or an oropharyngeal airway (in unconscious patients only), and endotracheal intubation. If intubation is impossible because of airway obstruction, an emergency cricothyroidotomy or tracheotomy is performed (see Chapter 27). Ventilate patients with 100% O2 using a bag-valve-mask (BVM) device before intubation or cricothyroidotomy.7 Rapid-sequence intubation is the preferred procedure for securing an unprotected airway in the ED. It involves the use of sedation (e.g., midazolam [Versed]) or anesthesia (e.g., etomidate [Amidate]) and paralysis (e.g., succinylcholine [Anectine]). These drugs aid intubation and reduce the risk of aspiration and airway trauma.7 (See Chapter 66 for more information on intubation.) An effective circulatory system includes the heart, intact blood vessels, and adequate blood volume. Uncontrolled internal or external bleeding places an individual at risk for hemorrhagic shock (see Chapter 67). Check a central pulse (e.g., carotid) because peripheral pulses may be absent due to direct injury or vasoconstriction. If you feel a pulse, assess the quality and rate. Assess the skin for color, temperature, and moisture. Altered mental status and delayed capillary refill (longer than 3 seconds) are common signs of shock. Take care when evaluating capillary refill in cold environments because cold delays refill. Insert IV lines into veins in the upper extremities unless contraindicated, such as in a massive fracture or an injury that affects limb circulation. Insert two large-bore (14- to 16-gauge) IV catheters and start aggressive fluid resuscitation using normal saline or lactated Ringer’s solution (see Chapter 67 for more information on hypovolemic shock and fluid resuscitation). Apply direct pressure with a sterile dressing followed by a pressure dressing to any obvious bleeding sites. Obtain blood samples for typing to determine ABO and Rh group. Give type-specific packed red blood cells if needed. In an emergency (life-threatening) situation, give uncrossmatched blood if immediate transfusion is warranted. Pelvic splints or belts for pelvic fracture may be used for bleeding with hypotension.8 Conduct a brief neurologic examination as part of the primary survey. The patient’s level of consciousness is a measure of the degree of disability. Determine the patient’s response to verbal and/or painful stimuli to assess level of consciousness. A simple mnemonic to remember is AVPU: A = alert, V = responsive to voice, P = responsive to pain, and U = unresponsive. In addition, use the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) to determine the level of consciousness (see Table 57-5). Finally, assess the pupils for size, shape, equality, and reactivity. The secondary survey begins after addressing each step of the primary survey and starting any lifesaving interventions. The secondary survey is a brief, systematic process that aims to identify all injuries9 (Table 69-5). TABLE 69-5 EMERGENCY ASSESSMENT: SECONDARY SURVEY • Continuously monitor ECG for heart rate and rhythm. • Continuously monitor O2 saturation and end-tidal carbon dioxide (if appropriate) (see Chapter 66). • Obtain portable chest x-ray to confirm exact placement of tubes (e.g., endotracheal, gastric). • Insert an indwelling catheter to decompress the bladder, monitor urine output, and check for hematuria. Do not insert an indwelling catheter if blood is present at the urinary meatus (e.g., urethral tear) or if scrotal hematoma or perineal ecchymosis is present. Men with a high-riding prostate gland on rectal examination are at risk for a urethral injury. The physician may order a retrograde urethrogram before inserting a catheter. • Insert orogastric or nasogastric tube to decompress and empty the stomach, reduce the risk of aspiration, and test the contents for blood. Place an orogastric tube in a patient with significant head or facial trauma, since a nasogastric tube could enter the brain. • Facilitate laboratory and diagnostic studies (e.g., type and crossmatch, complete blood count and metabolic panel, blood alcohol, toxicology screening, arterial blood gases [ABGs], coagulation profile, cardiac markers, pregnancy [urine], x-rays, computed tomography [CT] scans, ultrasound).

Nursing Management

Emergency, Terrorism, and Disaster Nursing

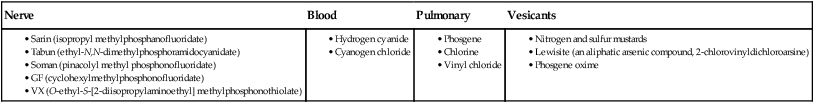

![]() TABLE 69-1

TABLE 69-1

Emergency Management Tables

Title

Chapter

Page

Abdominal Trauma

43

973

Acute Abdominal Pain

43

971

Acute Soft Tissue Injury

63

1507

Anaphylactic Shock

14

214

Chemical Burns

25

457

Chest Pain

34

750

Chest Trauma

28

541

Cocaine and Amphetamine Toxicity

11

164

Depressant Drug Overdose

11

164

Diabetic Ketoacidosis

49

1177

Dysrhythmias

36

793

Electrical Burns

25

456

Eye Injury

22

390

Fractured Extremity

63

1518

Head Injury

57

1372

Hyperthermia

69

1683

Hypothermia

69

1685

Inhalation Injury

25

456

Sexual Assault

54

1302

Shock

67

1641

Spinal Cord Injury

61

1474

Stroke

58

1398

Submersion Injuries

69

1687

Thermal Burns

25

455

Thoracic Injuries

28

542

Tonic-Clonic Seizures

59

1423

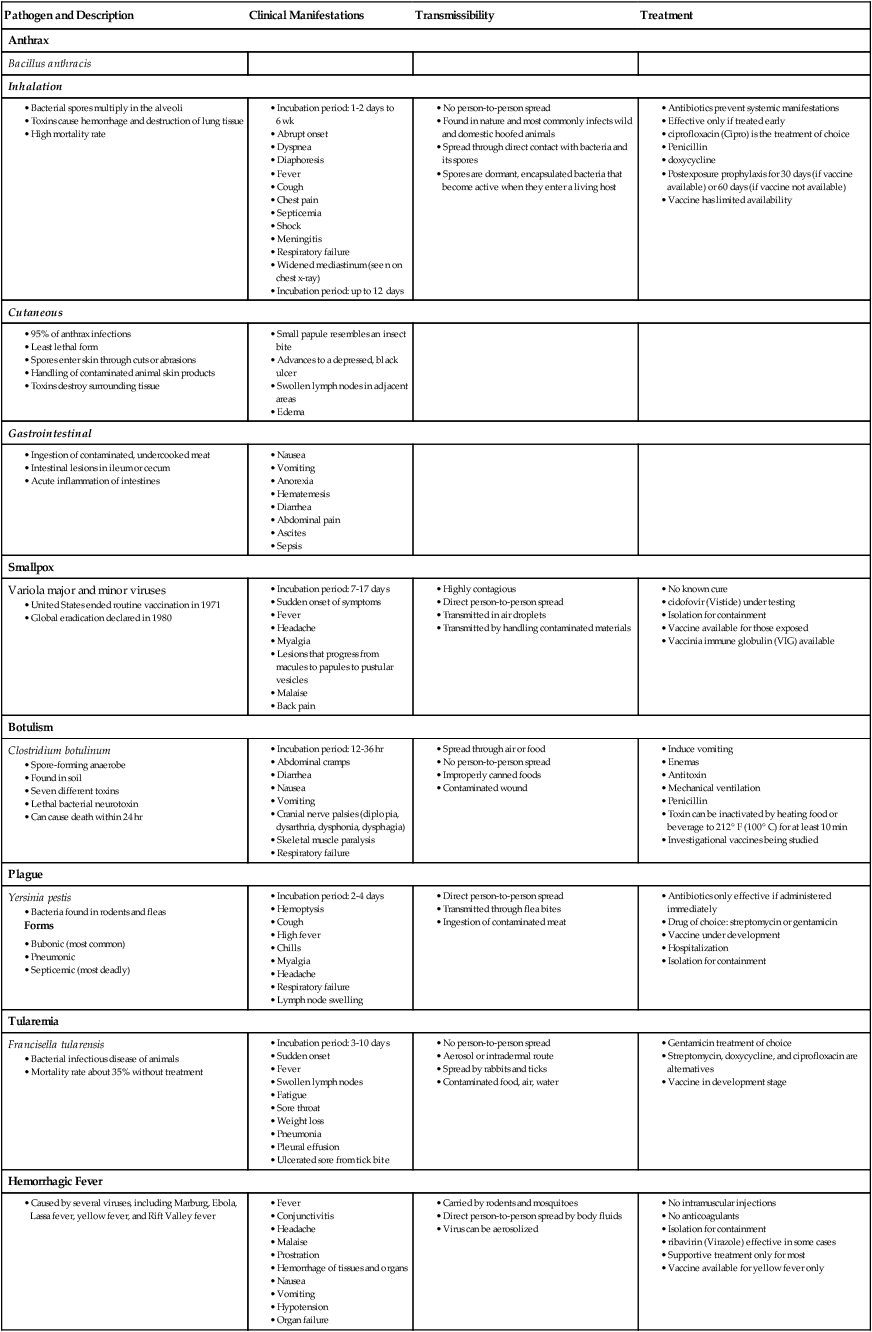

Pathogen and Description

Clinical Manifestations

Transmissibility

Treatment

Anthrax

Bacillus anthracis

Inhalation

Cutaneous

Gastrointestinal

Smallpox

Variola major and minor viruses

Botulism

Clostridium botulinum

Plague

Yersinia pestis

Tularemia

Francisella tularensis

Hemorrhagic Fever

Care of Emergency Patient

Triage

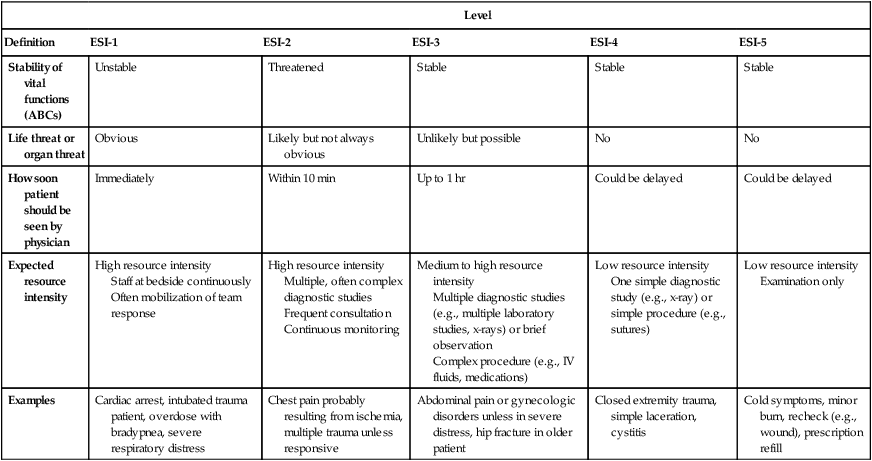

Level

Definition

ESI-1

ESI-2

ESI-3

ESI-4

ESI-5

Stability of vital functions (ABCs)

Unstable

Threatened

Stable

Stable

Stable

Life threat or organ threat

Obvious

Likely but not always obvious

Unlikely but possible

No

No

How soon patient should be seen by physician

Immediately

Within 10 min

Up to 1 hr

Could be delayed

Could be delayed

Expected resource intensity

High resource intensity

Staff at bedside continuously

Often mobilization of team response

High resource intensity

Multiple, often complex diagnostic studies

Frequent consultation

Continuous monitoring

Medium to high resource intensity

Multiple diagnostic studies (e.g., multiple laboratory studies, x-rays) or brief observation

Complex procedure (e.g., IV fluids, medications)

Low resource intensity

One simple diagnostic study (e.g., x-ray) or simple procedure (e.g., sutures)

Low resource intensity

Examination only

Examples

Cardiac arrest, intubated trauma patient, overdose with bradypnea, severe respiratory distress

Chest pain probably resulting from ischemia, multiple trauma unless responsive

Abdominal pain or gynecologic disorders unless in severe distress, hip fracture in older patient

Closed extremity trauma, simple laceration, cystitis

Cold symptoms, minor burn, recheck (e.g., wound), prescription refill

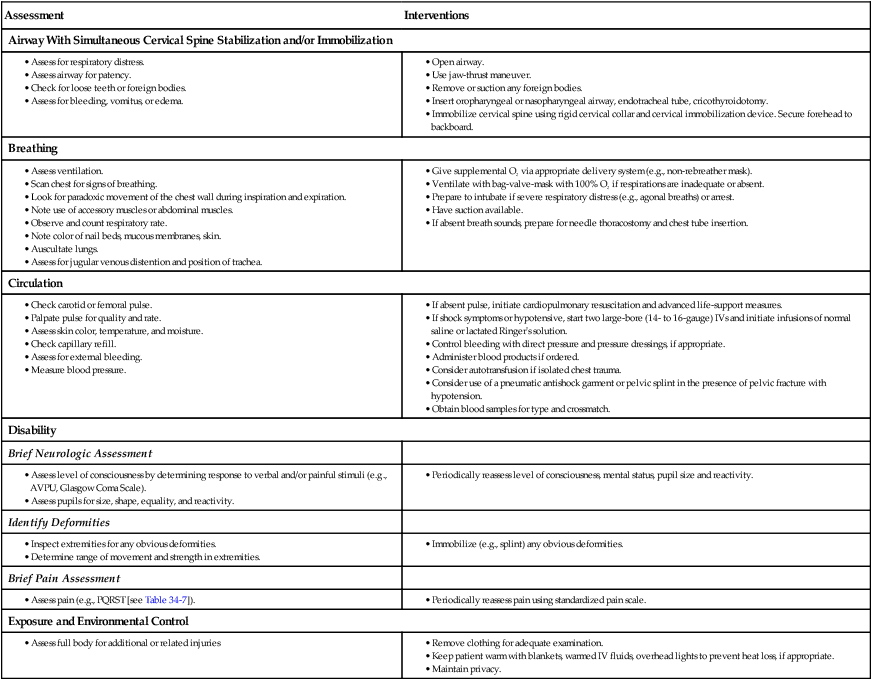

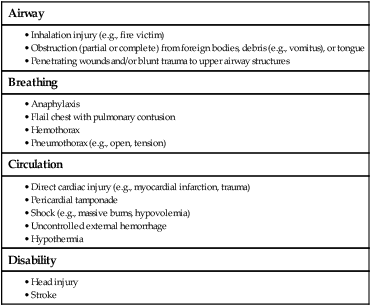

Primary Survey

Airway

Breathing

Circulation

Disability

A = Airway With Cervical Spine Stabilization and/or Immobilization.

C = Circulation.

D = Disability.

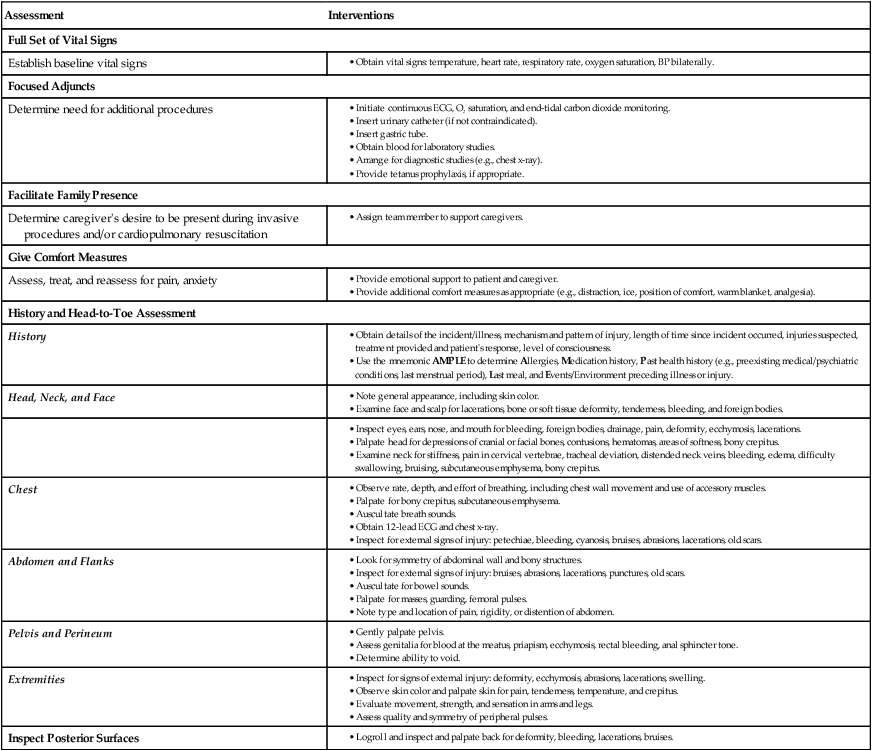

Secondary Survey

F = Full Set of Vital Signs, Focused Adjuncts, Facilitate Family Presence.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree