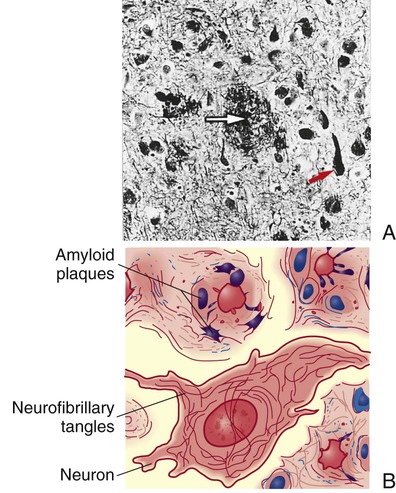

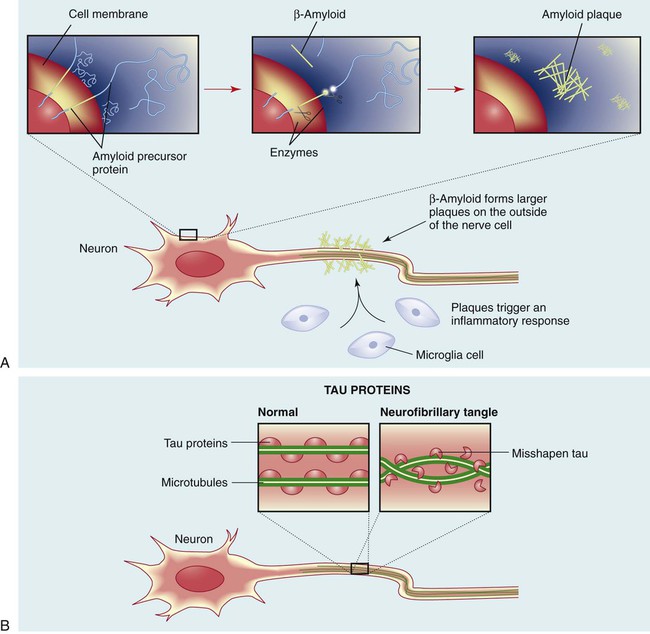

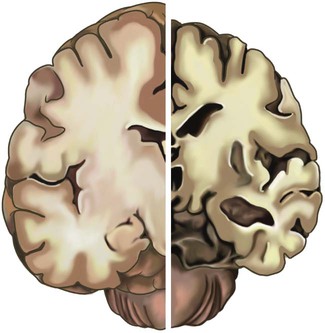

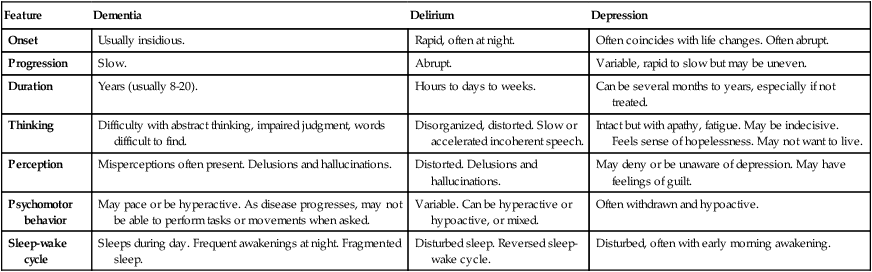

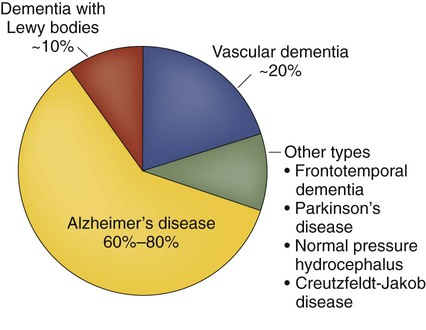

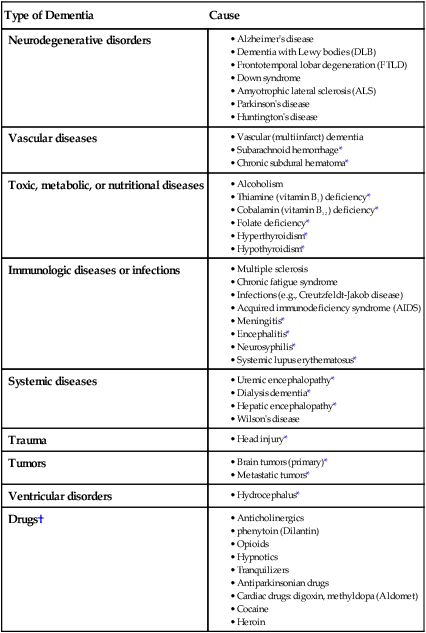

1. Define dementia and describe its impact on society. 2. Compare and contrast different etiologies of dementia. 3. Describe the clinical manifestations, diagnostic studies, and collaborative management of dementia. 4. Describe the clinical manifestations of mild cognitive impairment. 5. Describe the clinical manifestations, diagnostic studies, and collaborative management of Alzheimer’s disease. 6. Describe the nursing management of the patient with Alzheimer’s disease. 7. Differentiate among other neurodegenerative disorders associated with dementia, including dementia with Lewy bodies, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, and normal pressure hydrocephalus. 8. Describe the etiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, diagnostic studies, and collaborative management of delirium. The three most common cognitive problems in adults are dementia, delirium (acute confusion), and depression (Table 60-1). Although this chapter focuses on dementia and delirium, depression is often associated with these conditions. TABLE 60-1 COMPARISON OF DEMENTIA, DELIRIUM, AND DEPRESSION Fifteen percent of older Americans have dementia. As the average life span increases, the number of those affected with dementia is growing. There are about 100 causes of dementia, with about 60% to 80% of the patients with dementia having a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Fig. 60-1). In the United States, about half of all patients in long-term care facilities have AD or a related dementia.1 eTABLE 60-1 MINI-MENTAL STATE EXAMINATION (MMSE) Orientation to Time “What is the date?” Registration “Listen carefully, I am going to say three words. You say them back after I stop. Ready? Here they are . . . HOUSE (pause), CAR (pause), LAKE (pause). Now repeat those words back to me.” (Repeat up to five times, but score only the first trial.) Naming “What is this?” (Point to a pencil or pen.) Reading “Please read this and do what it says.” (Show examinee the words CLOSE YOUR EYES on the stimulus form.) Reproduced by special permission of the Publisher, Psychological Assessment Resource, Inc., 16204 North Florida Avenue, Lutz, Fla. 33549, from the Mini-Mental State Examination, by Marshal Folstein and Susan Folstein, Copyright 1975, 1998, 2001 by Mini-Mental, LLC, Inc. Published 2001 by Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. Further reproduction is prohibited without permission from PAR, Inc. The MMSE can be purchased from PAR, Inc., by calling 813-968-3003. Dementia is due to both treatable and nontreatable conditions (Table 60-2). The two most common causes of dementia are neurodegenerative conditions (e.g., AD) and vascular disorders. Dementia is sometimes caused by conditions that may initially be reversible (see Table 60-2). However, with prolonged exposure or disease, irreversible changes may occur. TABLE 60-2 †These are examples of drugs that may cause cognitive impairment that is potentially reversible. Vascular conditions are the second most common cause of dementia.1 Vascular dementia, also called multiinfarct dementia, is loss of cognitive function resulting from ischemic or hemorrhagic brain lesions caused by cardiovascular disease. This type of dementia is the result of decreased blood supply from narrowing and blocking of arteries that supply the brain. Vascular dementia may be caused by a single stroke (infarct) or by multiple strokes. The greatest risk factor for dementia is aging, although it is not a normal part of aging. Family history is also an important risk factor, since those with a first-degree relative with dementia are more likely to develop the disease. Those who have more than one first-degree relative with dementia are even at higher risk of developing the disease.1 Other risk factors for dementia are diabetes mellitus, obesity, smoking, cardiac dysrhythmias (e.g., atrial fibrillation), hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and coronary artery disease. Genetic factors (discussed on pp. 1446-1447) also contribute to the risk of dementia. Diabetes dramatically increases a person’s risk of developing AD or other types of dementia. Diabetes can contribute to dementia in several ways. Insulin resistance, which causes high blood glucose and in some cases leads to type 2 diabetes, may interfere with the body’s ability to break down amyloid, a protein that forms brain plaques in AD. High blood glucose also produces oxygen-containing molecules that can damage cells, in a process known as oxidative stress. In addition, high blood glucose along with high cholesterol has a role in atherosclerosis, which contributes to vascular dementia.2 Diabetes may contribute to poor memory and diminished mental function in various other ways. The disease causes microangiopathy, which damages small blood vessels throughout the body. Ongoing damage to blood vessels in the brain may be one reason why people with diabetes are at a higher risk of cognitive problems as they grow older. 2 Head trauma is also a risk factor for dementia. Professional football players and military veterans who had traumatic brain injury or posttraumatic stress disorder have an increased risk for AD and other types of dementia.3,4 Depression is often mistaken for dementia in older adults, and, conversely, dementia for depression. Manifestations of depression (especially in the older adult) include sadness, difficulty thinking and concentrating, fatigue, apathy, feelings of despair, and inactivity. When the depression is severe, poor concentration and attention may result, causing memory and functional impairment. When dementia and depression occur together (as happens in many patients with dementia), the intellectual deterioration can be extreme. Depression, alone or in combination with dementia, is treatable. The challenge is to make an accurate and early assessment and diagnosis (see Table 60-1). Other clinical manifestations of dementia are discussed in the section on clinical manifestations of AD on pp. 1447-1448. The diagnosis of dementia is focused on determining the cause (e.g., reversible versus irreversible factors). An important first step is a thorough medical, neurologic, and psychologic history. A thorough physical examination is performed to rule out other potential medical conditions. Screening for cobalamin (vitamin B12) deficiency and hypothyroidism is often performed. Based on patient history, testing for neurosyphilis (see Chapter 59) may be performed. In many ways, management of the patient with dementia is similar to management of the patient with AD (described later in this chapter). One form of dementia, vascular dementia, can often be prevented. Preventive measures include treatment of risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, smoking, hypercholesterolemia, and cardiac dysrhythmias. (Stroke is discussed in Chapter 58.) Drugs that are used for patients with AD are also useful in patients with vascular dementia. Drug therapy is discussed on p. 1452 later in this chapter. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a chronic, progressive, degenerative disease of the brain. It is the most common form of dementia, accounting for 60% to 80% of all cases of dementia.1 AD is named after Alois Alzheimer, a German physician who in 1906 described changes in the brain tissue of a 55-year-old woman who had died of an unusual mental illness. Approximately 5.2 million Americans suffer from AD. It is estimated that 11% of people age 65 and older, and nearly one third of those over age 85, have AD. Ultimately the disease is fatal, with death typically occurring 4 to 8 years after diagnosis, although some patients live for 20 years. AD is the sixth leading cause of death in the United States.1 It is the only cause of death among the top 10 in United States that cannot be prevented or cured, or its progression even slowed. The burden of care for the patient with AD on the family, caregivers, and society is staggering. AD has often been referred to as the “long good-bye” or “death in slow motion.” The incidence of AD is slightly higher in African Americans and Hispanic Americans than in whites. AD has been associated with lower socioeconomic status and education level and poor access to health care. Women are more likely than men to develop AD, primarily because they live longer (see the Gender Differences box). The exact etiology of AD is unknown, but is likely a combination of genetic and environmental factors. AD is not a normal part of aging, but as with other forms of dementia, age is the most important risk factor for developing AD. Only a small percentage of people younger than 60 years old develop AD. When AD develops in someone younger than 60 years old, it is referred to as early-onset AD. AD that becomes evident in individuals more than 60 years old is called late-onset AD (see the Genetics in Clinical Practice box). Characteristic findings of AD relate to changes in the brain’s structure and function: (1) amyloid plaques, (2) neurofibrillary tangles, (3) loss of connections between neurons, and (4) neuron death. Fig. 60-2 shows the pathologic changes in AD. β-Amyloid is cleaved from amyloid precursor protein (APP), which is associated with the cell membrane (Fig. 60-3). The normal function of APP is unknown. In AD, plaques develop first in areas of the brain used for memory and cognitive function, including the hippocampus (a structure that is important in forming and storing short-term memories). Eventually AD attacks the cerebral cortex, especially the areas responsible for language and reasoning. Neurofibrillary tangles are abnormal collections of twisted protein threads inside nerve cells. The main component of these structures is a protein called tau. Tau proteins in the central nervous system (CNS) are involved in providing support for intracellular structure through their support of microtubules. Tau proteins hold the microtubules together like railroad ties hold railroad tracks together. In AD the tau protein is altered, and as a result, the microtubules twist together in a helical fashion (see Fig. 60-3). This ultimately forms the neurofibrillary tangles found in the neurons of persons with AD. The other feature of AD is the loss of connections between neurons and neuron death. These processes result in structural damage. Affected parts of the brain begin to shrink in a process called brain atrophy. By the final stage of AD, brain tissue has shrunk significantly (Fig. 60-4).

Nursing Management

Alzheimer’s Disease, Dementia, and Delirium

Feature

Dementia

Delirium

Depression

Onset

Usually insidious.

Rapid, often at night.

Often coincides with life changes. Often abrupt.

Progression

Slow.

Abrupt.

Variable, rapid to slow but may be uneven.

Duration

Years (usually 8-20).

Hours to days to weeks.

Can be several months to years, especially if not treated.

Thinking

Difficulty with abstract thinking, impaired judgment, words difficult to find.

Disorganized, distorted. Slow or accelerated incoherent speech.

Intact but with apathy, fatigue. May be indecisive. Feels sense of hopelessness. May not want to live.

Perception

Misperceptions often present. Delusions and hallucinations.

Distorted. Delusions and hallucinations.

May deny or be unaware of depression. May have feelings of guilt.

Psychomotor behavior

May pace or be hyperactive. As disease progresses, may not be able to perform tasks or movements when asked.

Variable. Can be hyperactive or hypoactive, or mixed.

Often withdrawn and hypoactive.

Sleep-wake cycle

Sleeps during day. Frequent awakenings at night. Fragmented sleep.

Disturbed sleep. Reversed sleep-wake cycle.

Disturbed, often with early morning awakening.

Dementia

MMSE Sample Items

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Type of Dementia

Cause

Neurodegenerative disorders

Vascular diseases

Toxic, metabolic, or nutritional diseases

Immunologic diseases or infections

Systemic diseases

Trauma

Tumors

Ventricular disorders

Drugs†

Risk Factors.

Clinical Manifestations

Diagnostic Studies

Nursing and Collaborative Management Dementia

Alzheimer’s Disease

Etiology and Pathophysiology

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nursing Management: Alzheimer’s Disease, Dementia, and Delirium

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access