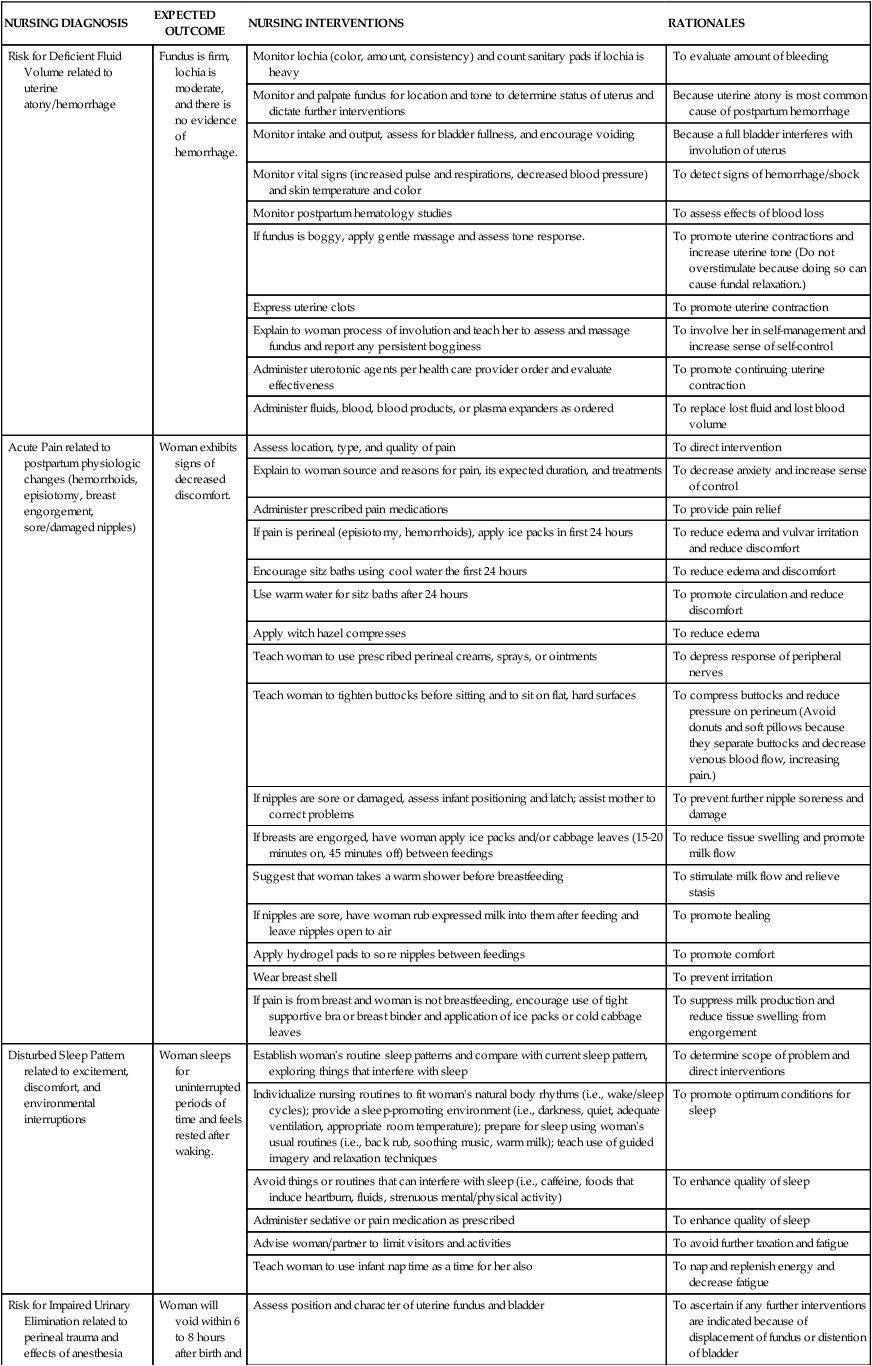

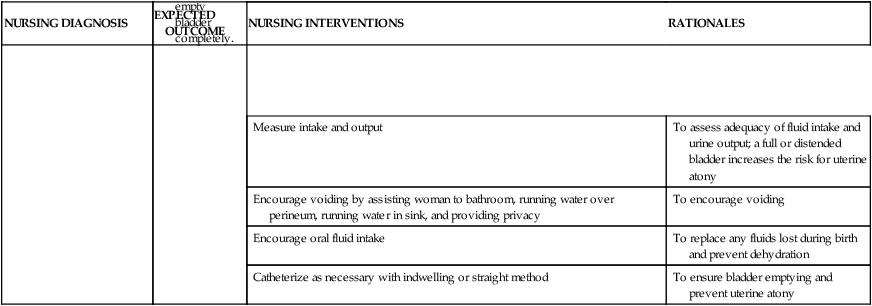

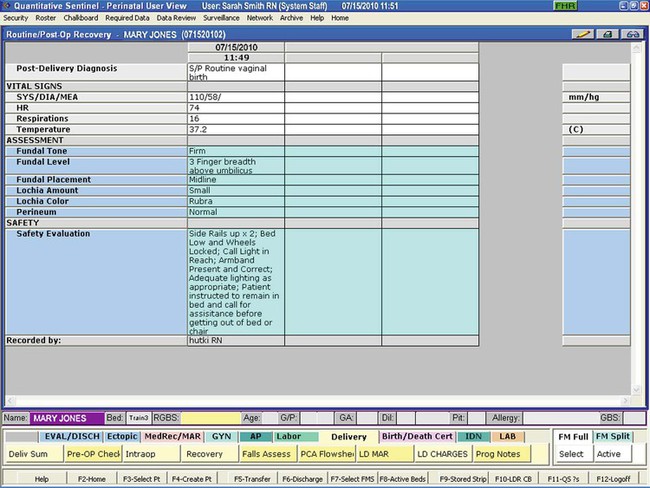

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Describe components of a systematic postpartum assessment. • Recognize signs of potential complications in the postpartum woman. • Identify common selection criteria for safe early postpartum discharge. • Formulate a nursing care plan for a woman in the postpartum period. • Explain the influence of cultural beliefs and practices on postpartum care. • Identify psychosocial needs of the woman in the early postpartum period. • Prepare a plan for postpartum teaching for self-management. • Describe the nurse’s role in these postpartum follow-up strategies: home visits, telephone follow-up, warm lines and help lines, support groups, and referrals to community resources. In preparing the transfer report, the recovery nurse uses information from the records of admission, labor and birth, and recovery (Fig. 19-1). Information communicated to the postpartum nurse includes identity of the health care provider; gravidity and parity; age; anesthetic used; any medications given; duration of labor and time of rupture of membranes; whether labor was induced or augmented; type of birth and repair; blood type and Rh status; group B streptococcus status; status of rubella immunity; human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B, and syphilis serology test results; other infections identified during pregnancy (e.g., chlamydia, gonorrhea) and whether these were treated; intravenous infusion of any fluids; physiologic status since birth; description of fundus, lochia, bladder, and perineum; sex and weight of infant; time of birth; name of pediatric care provider; chosen method of feeding; any abnormalities noted; and assessment of initial parent-infant interaction. Most of this information is also communicated to the nurse on the mother/baby unit or the nursing staff in the newborn nursery if the infant is transferred to that unit. In addition, specific information should be provided regarding the infant’s Apgar scores (see Chapter 23), weight, voiding, and stooling and whether fed since birth. Nursing interventions that have been completed (e.g., eye prophylaxis and vitamin K injection) and identification procedures (e.g., footprints, armbands) must be recorded. From their initial contact with the postpartum woman, nurses prepare the new mother for the time when she will return home. Planning for discharge begins with the first interaction between the nurse, the woman, and her family and continues until they leave the hospital or birthing facility (Fig. 19-2). Women who give birth in birthing centers may be discharged within a few hours, after the woman’s and infant’s conditions are stable. Mothers and newborns who are at low risk for complications may be discharged from the hospital within 24 to 36 hours after vaginal birth. This short time frame is often called early postpartum discharge, shortened hospital stay, or 1-day maternity stay. Early discharge was popular in the late 1980s and early 1990s, but concerns related to the health and well-being of mothers and newborns led to legislation promoting longer hospital stays. The passage of the Newborns’ and Mothers’ Health Protection Act of 1996 provided minimum federal standards for health plan coverage for mothers and their newborns (AAP Committee on Fetus and Newborn, 2010). Under this Act all health plans are required to allow the new mother and newborn to remain in the hospital for a minimum of 48 hours after an uncomplicated vaginal birth and for 96 hours after a cesarean birth, unless the attending provider in consultation with the mother decides on early discharge. The AAP (2010) recommends that the hospital stay for a mother with a healthy term newborn should be of sufficient length to identify early problems and determine that the mother and family are prepared and able to care for the neonate at home. The health of the mother and her newborn should be stable; the mother should be able and confident to provide care for her infant; there should be adequate support systems in place and access to follow-up care (AAP Committee on Fetus and Newborn, 2010). It is essential that nurses consider the individual needs of the woman and her newborn and provide care that is coordinated to meet these needs to provide timely physiologic interventions and treatment to prevent morbidity and hospital readmission. Hospital-based maternity nurses continue to play invaluable roles as caregivers, teachers, and advocates for mothers, newborns, and families in developing and implementing effective home-care strategies. Postpartum order sets and maternal-newborn teaching checklists can be used to accomplish patient care tasks and educational outcomes. With coordination, clinical care and education can be planned and provided throughout pregnancy, during the hospital stay, and in the home after discharge to promote and support the family’s continued well-being (see Evidence-Based Practice box). The nursing plan of care includes both the postpartum woman and her infant. It is also family centered, considering the needs and concerns of the family and focusing on family unity (Waller-Wise, 2012). Although in some hospitals the nursery nurse retains primary responsibility for the infant, most perinatal settings use the couplet or mother/baby model of care (AWHONN, 2010). Nurses in these settings have been educated in both mother and infant care and function as primary nurses for both mother and infant, even if the infant is kept in the nursery. This approach is a variation of rooming-in, in which the mother and infant room together and mother and nurse share the care of the infant. The organization of the mother’s care must take the newborn’s feeding and care needs into consideration. Ongoing assessments are performed throughout hospitalization. In addition to vital signs, physical assessment of the postpartum woman focuses on evaluation of the breasts, uterine fundus, lochia, perineum, bladder and bowel function, vital signs, and legs (Table 19-1). TABLE 19-1 POSTPARTUM ASSESSMENT AND SIGNS OF POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS *Homans’ sign may or may not be included in routine postpartum assessments; there is concern about its limited sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing venous thromboembolism. Based on the available data (e.g., medical record) and assessment findings, the nurse plans with the woman which nursing measures are appropriate and which are to be given priority. The nursing plan of care includes periodic assessments to detect deviations from normal physical changes, measures to relieve discomfort or pain, safety measures to prevent injury or infection, and teaching and counseling measures designed to promote the woman’s feelings of competence in self-management and newborn care. The spouse or partner, and other family members who are present can be included in the teaching. The nurse evaluates continuously and is ready to change the plan if indicated. Almost all hospitals use standardized care plans as a base. Nurses individualize care of the postpartum woman and neonate according to their specific needs (see Nursing Care Plan). Signs of potential problems that may be identified during the assessment process are listed in Table 19-1. Nurses discuss infant security precautions with the mother and her family because infant abductions are an ongoing concern. Between 1983 and 2012, 130 infants were abducted from health care facilities in the United States; most (58%) of the babies were taken from the mother’s room (National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, 2012). The Joint Commission (1999) calls for hospitals to have a management plan to prevent infant abductions. Such a plan might include security devices such as access control to the unit, closed-circuit television, computer monitoring systems, and electronic infant security systems in which tamper-proof tags are placed on the neonate immediately after birth and removed at the time of hospital discharge. The mother should be taught to check the identity of any person who comes to remove the baby from her room. Hospital personnel usually wear picture identification badges. On some units all staff members wear matching scrubs or special badges that are unique to the perinatal unit. As a rule the baby is never carried in a staff member’s arms between the mother’s room and the nursery but rather is always wheeled in a bassinet, which also contains baby care supplies. Patients and nurses must work together to ensure the safety of newborns in the hospital environment (Vincent, 2009). Perineal lacerations and episiotomies can increase the risk of infection as a result of interruption in skin integrity. Proper perineal care helps prevent infection in the genitourinary area and aids the healing process. Educating the woman to wipe from front to back (urethra to anus) after voiding or defecating is a simple first step. In many hospitals a squeeze bottle filled with warm water or an antiseptic solution is used after each voiding to cleanse the perineal area. The woman should change her perineal pad from front to back each time she voids or defecates and wash her hands thoroughly before and after doing so (Box 19-1).

Nursing Care of the Family During the Postpartum Period

Transfer from the Recovery Area

Planning for Discharge

Criteria for Discharge

Care Management—Physical Needs

Ongoing Physical Assessment

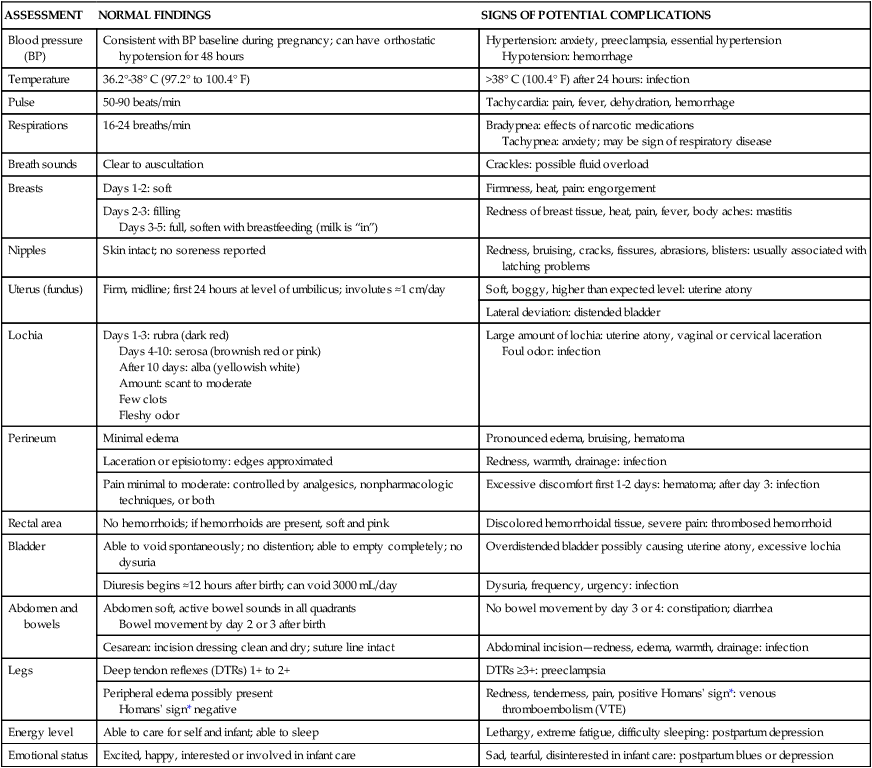

ASSESSMENT

NORMAL FINDINGS

SIGNS OF POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS

Blood pressure (BP)

Consistent with BP baseline during pregnancy; can have orthostatic hypotension for 48 hours

Hypertension: anxiety, preeclampsia, essential hypertension

Hypotension: hemorrhage

Temperature

36.2°-38° C (97.2° to 100.4° F)

>38° C (100.4° F) after 24 hours: infection

Pulse

50-90 beats/min

Tachycardia: pain, fever, dehydration, hemorrhage

Respirations

16-24 breaths/min

Bradypnea: effects of narcotic medications

Tachypnea: anxiety; may be sign of respiratory disease

Breath sounds

Clear to auscultation

Crackles: possible fluid overload

Breasts

Days 1-2: soft

Firmness, heat, pain: engorgement

Days 2-3: filling

Days 3-5: full, soften with breastfeeding (milk is “in”)

Redness of breast tissue, heat, pain, fever, body aches: mastitis

Nipples

Skin intact; no soreness reported

Redness, bruising, cracks, fissures, abrasions, blisters: usually associated with latching problems

Uterus (fundus)

Firm, midline; first 24 hours at level of umbilicus; involutes ≈1 cm/day

Soft, boggy, higher than expected level: uterine atony

Lateral deviation: distended bladder

Lochia

Days 1-3: rubra (dark red)

Days 4-10: serosa (brownish red or pink)

After 10 days: alba (yellowish white)

Amount: scant to moderate

Few clots

Fleshy odor

Large amount of lochia: uterine atony, vaginal or cervical laceration

Foul odor: infection

Perineum

Minimal edema

Pronounced edema, bruising, hematoma

Laceration or episiotomy: edges approximated

Redness, warmth, drainage: infection

Pain minimal to moderate: controlled by analgesics, nonpharmacologic techniques, or both

Excessive discomfort first 1-2 days: hematoma; after day 3: infection

Rectal area

No hemorrhoids; if hemorrhoids are present, soft and pink

Discolored hemorrhoidal tissue, severe pain: thrombosed hemorrhoid

Bladder

Able to void spontaneously; no distention; able to empty completely; no dysuria

Overdistended bladder possibly causing uterine atony, excessive lochia

Diuresis begins ≈12 hours after birth; can void 3000 mL/day

Dysuria, frequency, urgency: infection

Abdomen and bowels

Abdomen soft, active bowel sounds in all quadrants

Bowel movement by day 2 or 3 after birth

No bowel movement by day 3 or 4: constipation; diarrhea

Cesarean: incision dressing clean and dry; suture line intact

Abdominal incision—redness, edema, warmth, drainage: infection

Legs

Deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) 1+ to 2+

DTRs ≥3+: preeclampsia

Peripheral edema possibly present

Homans’ sign* negative

Redness, tenderness, pain, positive Homans’ sign*: venous thromboembolism (VTE)

Energy level

Able to care for self and infant; able to sleep

Lethargy, extreme fatigue, difficulty sleeping: postpartum depression

Emotional status

Excited, happy, interested or involved in infant care

Sad, tearful, disinterested in infant care: postpartum blues or depression

Nursing Interventions

Prevention of Infection

Nursing Care of the Family During the Postpartum Period

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access