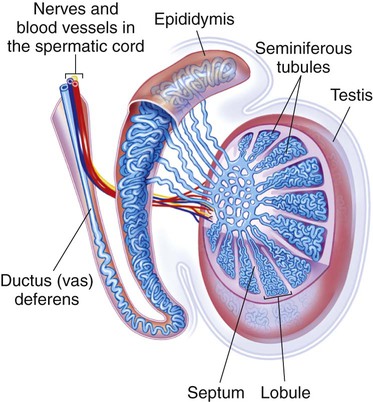

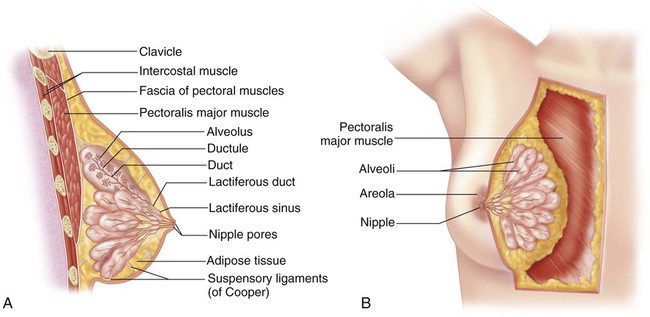

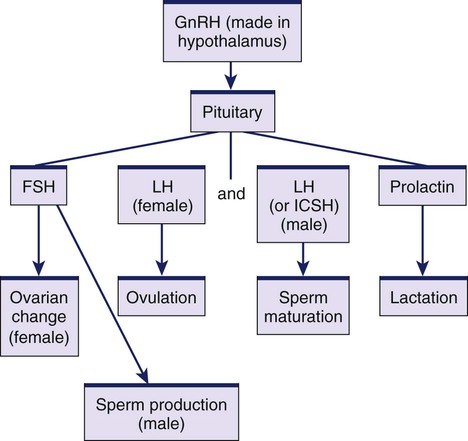

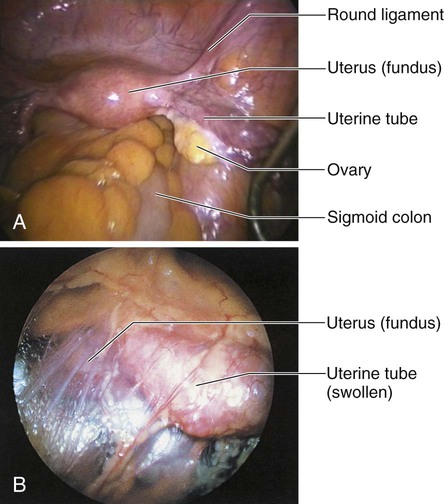

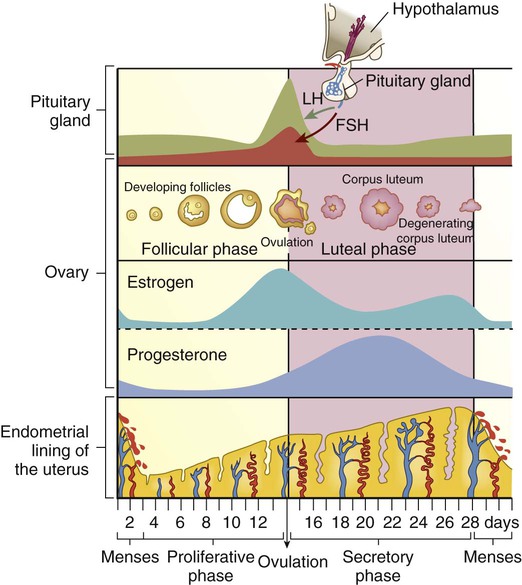

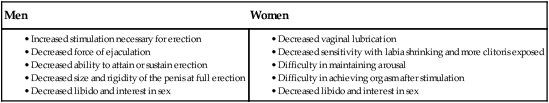

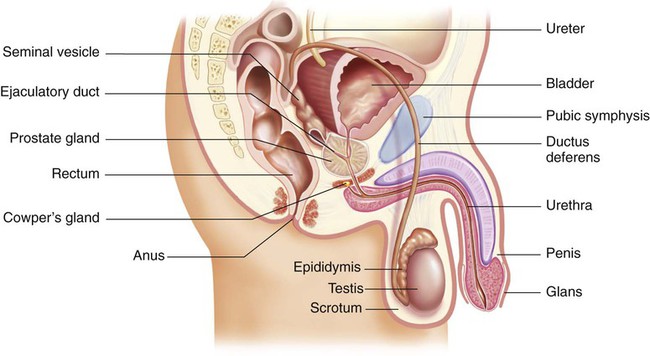

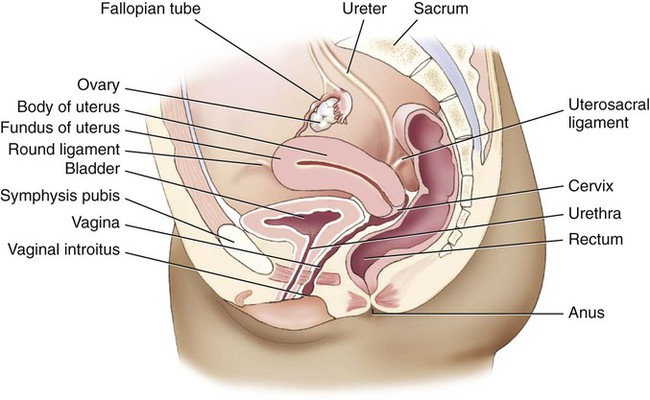

Chapter 51 1. Describe the structures and functions of the male and female reproductive systems. 2. Summarize the functions of the major hormones essential for the functioning of the male and female reproductive systems. 3. Explain the physiologic changes during the stages of sexual response for both a man and a woman. 4. Link the age-related changes of the male and female reproductive systems to the differences in assessment findings. 5. Select the significant subjective and objective data related to the male and female reproductive systems and information about sexual function that should be obtained from a patient. 6. Select the appropriate techniques to use in the physical assessment of the male and female reproductive systems. 7. Differentiate normal from common abnormal findings of a physical assessment of the male and female reproductive systems. 8. Describe the purpose, significance of results, and nursing responsibilities related to diagnostic studies of the male and female reproductive systems. The three primary roles of the male reproductive system are (1) production and transportation of sperm, (2) deposition of sperm in the female reproductive tract, and (3) secretion of hormones. The primary reproductive organs in the male are the testes. Secondary reproductive organs include ducts (epididymis, ductus deferens, ejaculatory duct, and urethra), sex glands (prostate gland, Cowper’s glands, and seminal vesicles), and the external genitalia (scrotum and penis)1 (Fig. 51-1). The epididymis is a comma-shaped structure located on the posterosuperior aspect of each testis within the scrotum (see Figs. 51-1 and 51-2). It is a very long, tightly coiled structure that measures about 20 ft in length.1 The epididymis transports the sperm as they mature. Sperm exit the epididymis through a long, thick tube known as the ductus deferens. The ductus deferens (also known as the vas deferens) is continuous with the epididymis within the scrotal sac. It travels upward through the scrotum and continues through the inguinal ring into the abdominal cavity. The spermatic cord is composed of a connective tissue sheath that encloses the ductus deferens, arteries, veins, nerves, and lymph vessels as it ascends up through the inguinal canal (see Fig. 51-2). In the abdominal cavity, the ductus deferens travels up, over, and behind the bladder. Posterior to the bladder the ductus deferens joins the seminal vesicle to form the ejaculatory duct (see Fig. 51-1). The ovaries are located on either side of the uterus, just behind and below the fallopian (uterine) tubes (Fig. 51-3). The almond-shaped ovaries are firm and solid, approximately 0.6 in (1.5 cm) wide and 1.2 in (3 cm) long. Their functions include ovulation and secretion of the two major reproductive hormones, estrogen and progesterone. The uterus is a pear-shaped, hollow, muscular organ (see Fig. 51-3). It is located between the bladder and the rectum. In the mature nulliparous (never pregnant) woman, the uterus is approximately 2.4 to 3.2 in (6 to 8 cm) long and 1.6 in (4 cm) wide. The uterine walls consist of an outer serosal layer, the perimetrium; a middle muscular layer, the myometrium; and an inner mucosal layer, the endometrium. The uterus consists of the fundus, body (or corpus), and cervix (see Fig. 51-3). The body makes up about 80% of the uterus and connects with the cervix at the isthmus, or neck. The cervix is the lower portion of the uterus that projects into the anterior wall of the vaginal canal. It makes up about 15% to 20% of the uterus in the nulliparous female. The cervix consists of the ectocervix, the outer portion that protrudes into the vagina, and the endocervix, the canal in the opening of the cervix. The ectocervix is covered with squamous epithelial cells, which give it a smooth, pinkish appearance. The endocervix contains a lining of columnar epithelial cells, which give it a rough, reddened appearance. The junction at which the two types of epithelial cells meet is termed the squamocolumnar junction and contains the optimal types of cells needed for an accurate Papanicolaou (Pap) test to screen for malignancies. The external portion of the female reproductive system (Fig. 51-4), commonly called the vulva, consists of the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, urethral meatus, Skene’s glands, vaginal introitus (opening), and Bartholin’s glands. Ducts of the Skene’s glands lie alongside the urinary meatus and are thought to help lubricate the urinary meatus.2 The Bartholin’s glands, located at the posterior and lateral aspects of the vaginal orifice, secrete a thin, mucoid material believed to contribute slightly to lubrication during sexual intercourse. These glands are not usually palpable unless sebaceous-like cysts form or they are swollen in the presence of an infection, such as a sexually transmitted infection (STI). The breasts extend from the second to the sixth ribs, with the tail reaching the axilla (Fig. 51-5). The fully mature breast is dome shaped and contains a pigmented center termed the areola. The areolar region contains Montgomery’s tubercles, which are similar to sebaceous glands and assist in lubricating the nipple. During lactation, the alveoli secrete milk. The milk then flows into a ductal system and is transported to the lactiferous sinuses. The nipple contains 15 to 20 tiny openings through which the milk flows during breastfeeding. The fibrous and fatty tissue that supports and separates the channels of the mammary duct system is primarily responsible for the varying sizes and shapes of the breasts in different individuals. The breast has a rich lymphatic network that drains into axillary and clavicular channels (see Fig. 52-5). Superficial lymph nodes are located in the axilla and are accessible to examination. This system is often responsible for the metastasis of a malignant tumor from the breast to other parts of the body. The hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and gonads secrete numerous hormones (Fig. 51-6). (Endocrine hormones are discussed in Chapter 48.) These hormones regulate the processes of ovulation, spermatogenesis (formation of sperm), and fertilization and the formation and function of the secondary sex characteristics. The hypothalamus secretes gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which stimulates the anterior pituitary gland to secrete its hormones, including FSH and LH. LH in males is sometimes called interstitial cell–stimulating hormone (ICSH). The gonadal hormones are estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone. In women, FSH production by the anterior pituitary stimulates the growth and maturity of the ovarian follicles necessary for ovulation.3 The mature follicle produces estrogen, which in turn suppresses the release of FSH. Another hormone, inhibin, is also secreted by the ovarian follicle and inhibits both GnRH and FSH secretion. In men, FSH stimulates the seminiferous tubules to produce sperm. The circulating levels of gonadal hormones are controlled primarily by a negative feedback process. Receptors within the hypothalamus and pituitary are sensitive to the circulating blood levels of the hormones (Table 51-1). Increased levels of hormones stimulate a hypothalamic response to decrease the high circulating levels. Likewise, low circulating levels provoke a hypothalamic response that increases the low circulating levels. For example, if the circulating level of testosterone in men is low, the hypothalamus is stimulated to secrete GnRH. This triggers the anterior pituitary to secrete greater amounts of FSH and LH, which in turn causes an increase in the production of testosterone. The high level of testosterone signals a decrease in the production of GnRH and thus of FSH and LH. TABLE 51-1 The major functions of the ovaries are ovulation and the secretion of hormones. These functions are accomplished during the normal menstrual cycle, a monthly process mediated by the hormonal activity of the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and ovaries. Menstruation occurs during each month in which an egg is not fertilized (Fig. 51-7). The endometrial cycle is divided into three phases labeled in relation to uterine and ovarian changes: (1) the proliferative, or follicular, phase; (2) the secretory, or luteal, phase; and (3) the menstrual, or ischemic, phase. The length of the menstrual cycle ranges from 21 to 35 days, with an average of 28 days.4 The menstrual cycle begins on the first day of menstruation, which usually lasts 4 to 6 days. Table 51-2 includes characteristics of the menstrual cycle and related teaching. During menstruation, estrogen and progesterone levels are low, but FSH levels begin to increase. During the follicular phase, a single follicle matures fully under the stimulation of FSH. (The mechanism that ensures that usually only one follicle reaches maturity is not known.) The mature follicle stimulates estrogen production, causing a negative feedback with resulting decreased FSH secretion. TABLE 51-2 PATIENT TEACHING GUIDE With ovulation and the resulting increased levels of progesterone, the luteal (or secretory) phase begins. If the corpus luteum regresses (when fertilization does not occur) and estrogen and progesterone levels fall, the endometrial lining can no longer be supported. As a result, the blood vessels contract, and tissue begins to slough (fall away). This sloughing results in the menses and the start of the menstrual phase.4 The sexual response is a complex interplay of psychologic and physiologic phenomena and is influenced by a number of variables (e.g., stress, illness). The changes that occur during sexual excitement are similar for men and women. Masters and Johnson described the sexual response in terms of the excitement, plateau, orgasmic, and resolution phases.5 With advancing age, changes occur in the male and female reproductive systems (Table 51-3). In women many of these changes are related to the altered estrogen production that is associated with menopause.6 A reduction in circulating estrogen along with an increase in androgens in postmenopausal women is associated with breast and genital atrophy, reduction in bone mass, and increased rate of atherosclerosis. Vaginal dryness may occur, which can lead to urogenital atrophy and changes in the composition of vaginal secretions. TABLE 51-3 GERONTOLOGIC ASSESSMENT DIFFERENCES A gradual testosterone decline in older men occurs. Manifestations of hormonal decline in men can be physical, psychologic, or sexual. Some of the changes include an increase in prostate size and a decrease in testosterone level, sperm production, muscle tone of the scrotum, and size and firmness of the testicles. Erectile dysfunction and sexual dysfunction occur in some men as a result of these changes.7 Rubella is of primary concern to women of childbearing age. If rubella occurs during the first 3 months of pregnancy, the possibility of congenital anomalies is increased. For this reason, you should encourage immunization for all women of childbearing age who have not been immunized for rubella or have not already had the disease. (Rubella immunity can be determined by antibody titers.) However, women should not be immunized if they are already pregnant.8 Advise women not to conceive for at least 3 months after immunization.

Nursing Assessment

Reproductive System

Structures and Functions of Male and Female Reproductive Systems

Male Reproductive System

Ducts.

Female Reproductive System

Pelvic Organs

Ovaries.

Uterus.

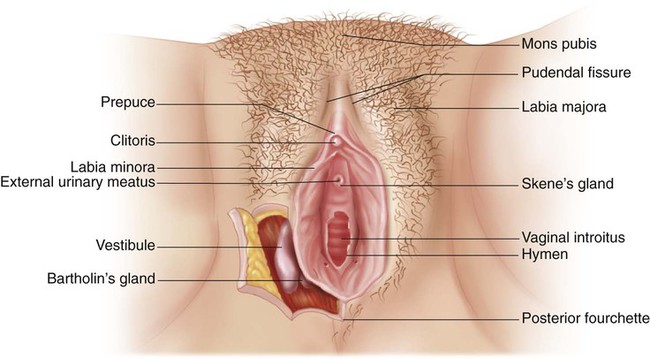

External Genitalia.

Breasts.

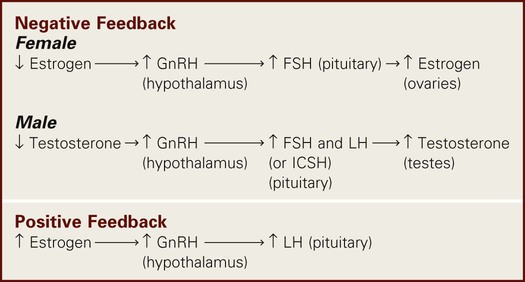

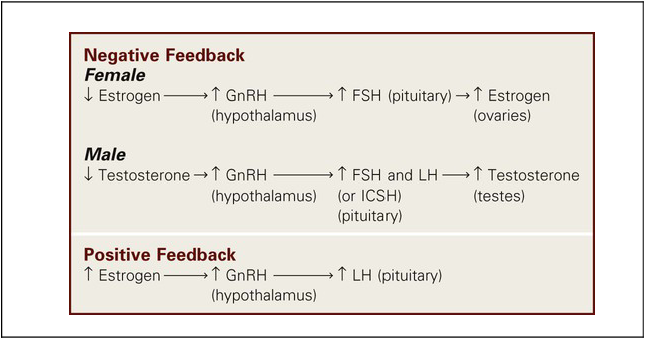

Neuroendocrine Regulation of Reproductive System

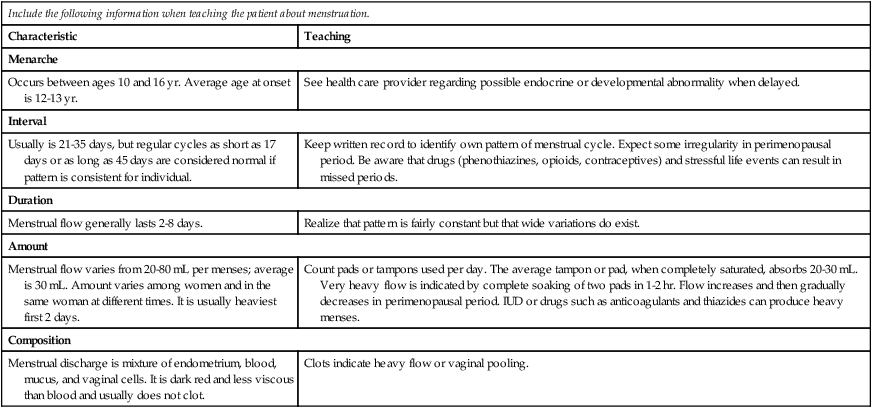

Menstrual Cycle

Characteristics of Menstruation

Include the following information when teaching the patient about menstruation.

Characteristic

Teaching

Menarche

Occurs between ages 10 and 16 yr. Average age at onset is 12-13 yr.

See health care provider regarding possible endocrine or developmental abnormality when delayed.

Interval

Usually is 21-35 days, but regular cycles as short as 17 days or as long as 45 days are considered normal if pattern is consistent for individual.

Keep written record to identify own pattern of menstrual cycle. Expect some irregularity in perimenopausal period. Be aware that drugs (phenothiazines, opioids, contraceptives) and stressful life events can result in missed periods.

Duration

Menstrual flow generally lasts 2-8 days.

Realize that pattern is fairly constant but that wide variations do exist.

Amount

Menstrual flow varies from 20-80 mL per menses; average is 30 mL. Amount varies among women and in the same woman at different times. It is usually heaviest first 2 days.

Count pads or tampons used per day. The average tampon or pad, when completely saturated, absorbs 20-30 mL. Very heavy flow is indicated by complete soaking of two pads in 1-2 hr. Flow increases and then gradually decreases in perimenopausal period. IUD or drugs such as anticoagulants and thiazides can produce heavy menses.

Composition

Menstrual discharge is mixture of endometrium, blood, mucus, and vaginal cells. It is dark red and less viscous than blood and usually does not clot.

Clots indicate heavy flow or vaginal pooling.

Phases of Sexual Response

Gerontologic Considerations

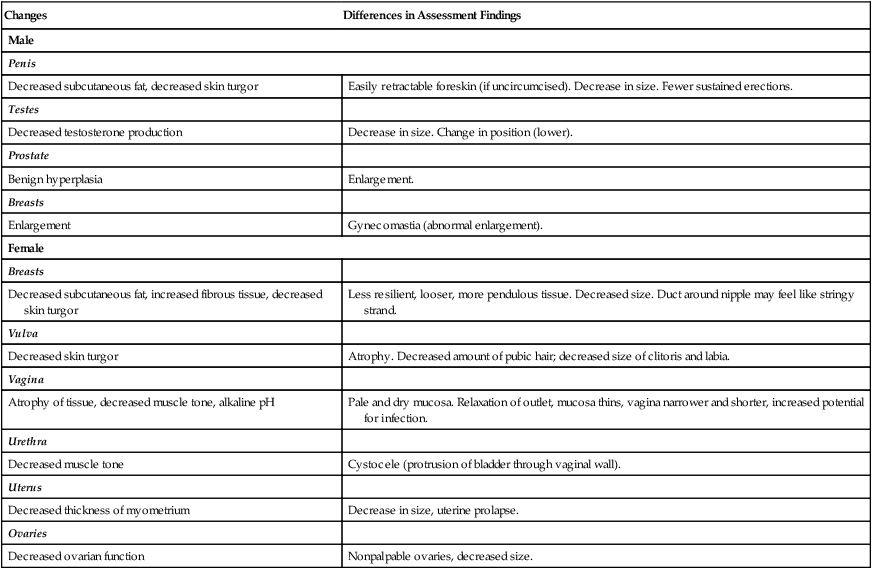

Effects of Aging on Reproductive Systems

Reproductive Systems

Changes

Differences in Assessment Findings

Male

Penis

Decreased subcutaneous fat, decreased skin turgor

Easily retractable foreskin (if uncircumcised). Decrease in size. Fewer sustained erections.

Testes

Decreased testosterone production

Decrease in size. Change in position (lower).

Prostate

Benign hyperplasia

Enlargement.

Breasts

Enlargement

Gynecomastia (abnormal enlargement).

Female

Breasts

Decreased subcutaneous fat, increased fibrous tissue, decreased skin turgor

Less resilient, looser, more pendulous tissue. Decreased size. Duct around nipple may feel like stringy strand.

Vulva

Decreased skin turgor

Atrophy. Decreased amount of pubic hair; decreased size of clitoris and labia.

Vagina

Atrophy of tissue, decreased muscle tone, alkaline pH

Pale and dry mucosa. Relaxation of outlet, mucosa thins, vagina narrower and shorter, increased potential for infection.

Urethra

Decreased muscle tone

Cystocele (protrusion of bladder through vaginal wall).

Uterus

Decreased thickness of myometrium

Decrease in size, uterine prolapse.

Ovaries

Decreased ovarian function

Nonpalpable ovaries, decreased size.

Assessment of Male and Female Reproductive Systems

Subjective Data

Important Health Information.

Past Health History.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nursing Assessment: Reproductive System

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access