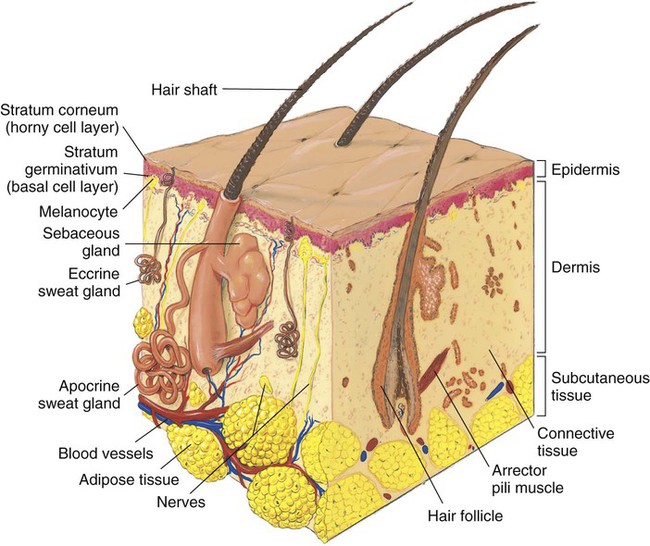

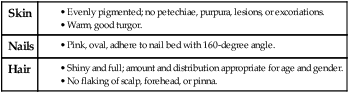

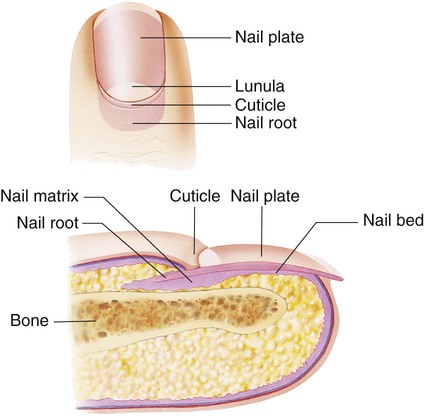

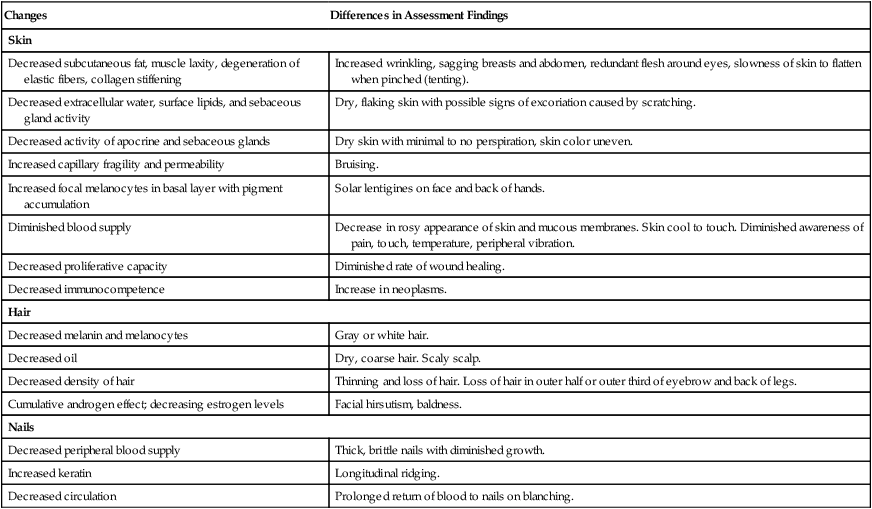

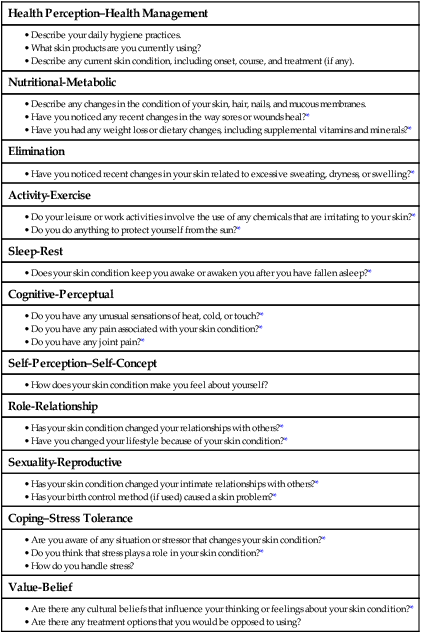

1. Describe the structures and functions of the integumentary system. 2. Link the age-related changes in the integumentary system to differences in assessment findings. 3. Select the significant subjective and objective data related to the integumentary system that should be obtained from a patient. 4. Describe specific assessments to be made during the physical examination of the skin and the appendages. 5. Compare and contrast the critical components for describing primary and secondary lesions. 6. Select appropriate techniques to use in the physical assessment of the integumentary system. 7. Specify the structural and assessment differences in light- and dark-skinned individuals. 8. Differentiate normal from common abnormal findings of a physical assessment of the integumentary system. 9. Describe the purpose, significance of results, and nursing responsibilities related to diagnostic studies of the integumentary system. The integumentary system is the largest body organ and is composed of the skin, hair, nails, and glands. The skin is further divided into two layers: the epidermis and the dermis. The subcutaneous tissue is immediately under the dermis (Fig. 23-1). Melanocytes are contained in the deep, basal layer (stratum germinativum) of the epidermis. They contain melanin, a pigment that gives color to the skin and hair and protects the body from damaging ultraviolet (UV) sunlight. Sunlight and hormones stimulate the melanosome (within the melanocyte) to increase the production of melanin.1 The wide range of skin color is caused by the amount of melanin produced; more melanin results in darker skin color.2 Hair grows on most of the body except for the lips, the palms of the hands, and the soles of the feet.3 The color of the hair is a result of heredity and is determined by the type and amount of melanin in the hair shaft. Hair grows approximately 1 cm per month. On average 100 hairs are lost each day. The rate of growth is not affected by cutting.2 When lost hair is not replaced, baldness results. The absence of hair may be related to disease, treatment, or heredity. Nails grow from the matrix. The nail matrix is located at the proximal area of the nail plate. The matrix is commonly called the lunula, which is the white crescent-shaped area visible through the nail plate (Fig. 23-2). The nail bed that is under the nail matrix and nail plate is normally pink and contains blood vessels. The nail plate adheres to and is supported by the nail bed. The cuticle is part of the skin that extends a small distance on the nail plate before being shed (like the stratum corneum). The nail root is bordered by the cuticle and hidden by a fold of skin. Fingernails grow at a rate of 0.7 to 0.84 mm per week, with toenail growth 30% to 50% slower. Nails can be injured by direct trauma. A lost fingernail usually regenerates in 3 to 6 months, whereas a lost toenail may require 12 months or longer for regeneration. Nail growth may vary according to the person’s age and health. Nail color ranges from pink to yellow or brown depending on skin color. Pigmented longitudinal bands (melanonychia striata) may commonly occur in the nail bed in approximately 90% or more of all people with dark skin (Fig. 23-3). Many skin changes are associated with aging. Although many changes are not serious except for their cosmetic value, others are more serious and need careful evaluation. Age-related changes of the integumentary system and differences in assessment findings are listed in Table 23-1. TABLE 23-1 GERONTOLOGIC ASSESSMENT DIFFERENCES Chronic UV exposure is the major contributor to the photoaging and wrinkling of skin.4 Sun damage to the skin is cumulative (Fig. 23-4). The wrinkling of sun-exposed areas such as the face and hands is more marked than that of a sun-shielded area such as the buttocks. Poor nutrition, with decreased intake of protein, calories, and vitamins, also contributes to aging of the skin. With aging, collagen fibers stiffen, elastic fibers degenerate, and the amount of subcutaneous tissue decreases. These changes, with the added effects of gravity, lead to wrinkling. The visible effects of aging on the skin and hair may have a profound psychologic effect. A youthful look may be tied to a person’s self-image. Although fine wrinkling of the skin, thinning hair, and brittle nails are normal changes with aging, they may result in an altered self-image.5 A general assessment of the skin begins at the initial contact with the patient and continues throughout the examination. Specific areas of the skin are assessed during the examination of other body systems unless the chief complaint is a dermatologic problem. Record a general statement about the skin’s physical condition (Table 23-2). In addition, ask the health history questions presented in Table 23-3 when a skin problem is noted. TABLE 23-3 HEALTH HISTORY

Nursing Assessment

Integumentary System

Structures and Functions of Skin and Appendages

Structures

Epidermis.

Skin Appendages.

Gerontologic Considerations

Effects of Aging on Integumentary System

Integumentary System

Changes

Differences in Assessment Findings

Skin

Decreased subcutaneous fat, muscle laxity, degeneration of elastic fibers, collagen stiffening

Increased wrinkling, sagging breasts and abdomen, redundant flesh around eyes, slowness of skin to flatten when pinched (tenting).

Decreased extracellular water, surface lipids, and sebaceous gland activity

Dry, flaking skin with possible signs of excoriation caused by scratching.

Decreased activity of apocrine and sebaceous glands

Dry skin with minimal to no perspiration, skin color uneven.

Increased capillary fragility and permeability

Bruising.

Increased focal melanocytes in basal layer with pigment accumulation

Solar lentigines on face and back of hands.

Diminished blood supply

Decrease in rosy appearance of skin and mucous membranes. Skin cool to touch. Diminished awareness of pain, touch, temperature, peripheral vibration.

Decreased proliferative capacity

Diminished rate of wound healing.

Decreased immunocompetence

Increase in neoplasms.

Hair

Decreased melanin and melanocytes

Gray or white hair.

Decreased oil

Dry, coarse hair. Scaly scalp.

Decreased density of hair

Thinning and loss of hair. Loss of hair in outer half or outer third of eyebrow and back of legs.

Cumulative androgen effect; decreasing estrogen levels

Facial hirsutism, baldness.

Nails

Decreased peripheral blood supply

Thick, brittle nails with diminished growth.

Increased keratin

Longitudinal ridging.

Decreased circulation

Prolonged return of blood to nails on blanching.

Assessment of Integumentary System

Integumentary System

Health Perception–Health Management

Nutritional-Metabolic

Elimination

Activity-Exercise

Sleep-Rest

Cognitive-Perceptual

Self-Perception–Self-Concept

Role-Relationship

Sexuality-Reproductive

Coping–Stress Tolerance

Value-Belief

Nursing Assessment: Integumentary System

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access