Mood Disorders

Mood disorders encompass a large group of disorders in which pathological mood and related disturbances dominate the clinical picture. Previously referred to as affective disorders, the term mood disorders is preferred because it refers to sustained emotional states, not merely the external or affective expression of a transitory emotional state.

Learning objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Briefly describe the historical perspective of mood disorders.

Explain the following theories of mood disorders: genetic, biochemical, biologic, psychodynamic, behavioral, cognitive, and life events and environmental.

Recognize the primary risk factors for developing mood disorders.

Differentiate among the clinical symptoms of major depressive disorder, bipolar I disorder, and bipolar II disorder.

Articulate the rationale for the use of the diagnosis mood disorder due to a general medical condition.

Compare and contrast the clinical symptoms of dysthymic disorder, cyclothymic disorder, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, and mood disorder with postpartum onset.

Articulate the rationale for each of the following modes of treatment for mood disorders: medication management, somatic therapy, interactive therapy, and complementary and alternative therapy.

Formulate an education guide for clients with a mood disorder.

Construct a sample plan of care for an individual exhibiting clinical symptoms of major depressive disorder.

Key Terms

Affective disorders

Anaclitic depression

Anergia

Anhedonia

Apathy

Asthenia

Bipolar disorder

Depressive disorders

Dysthymia

Elation

Endogenous depression

Euphoria

Hypomania

Mania

Poverty of speech content

Psychomotor agitation

Psychomotor retardation

Rapid-cycling

Residual symptoms

Mood disorders (previously referred to as affective disorders) encompass a large group of disorders involving pathological mood and related disturbances. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) divides mood disorders into two main categories: depressive disorders and bipolar disorders (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000). Mood disorders are one of the most commonly occurring psychiatric–mental health disorders. Only alcoholism and phobias are more common. Mood disorders impose an enormous burden on the individual, the family, and society as a whole (Grant & Morrison, 2001; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH, 2005) and the National Association for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD, 2005), have released the following statistics regarding the prevalence of mood disorders affecting American adults 18 years of age or older in any given year. Approximately 18.8 million adults (or 9.5% of the U.S. population) experience depressive disorders. Furthermore, major depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide. It affects approximately 9.9 million adults (or about 5.0 percent of the U.S. population). Nearly twice as many women (6.5 %) as men (3.3 %) suffer from a major depressive disorder. Statistics also reveal that more than 2.3 million adults (or about 1.2 % of the U.S. population) are diagnosed with bipolar disorder (BPD). Men and women are equally likely to develop BPD. By the year 2020, mood disorders are estimated to be the second most important cause of disability worldwide.

The direct costs of treatment for a major mood disorder, combined with the direct costs from lost productivity, are significant and have been estimated to account for approximately $12 billion to $16 billion per year in the United States. Indirect cost, including mortality, work absenteeism, and disability, have been estimated to exceed $32 billion per year (Grant & Morrison, 2001).

Mood disorders can occur in any age group. Infants may exhibit signs of anaclitic depression (withdrawal, nonresponsiveness, depression, and vulnerability to physical illness) or failure to thrive when separated from their mothers. School-aged children may experience a mood disorder along with anxiety, exhibiting behaviors such as hyperactivity, school phobia, or excessive clinging to parents. Adolescents experiencing depression may exhibit poor academic performance; abuse substances; display antisocial behavior, sexual promiscuity, truancy, or running-away behavior; or attempt suicide (for more information, see Chapters 29 and 31).

Although mood disorders are less common in the older adult than in younger individuals, symptoms of depression are present in approximately 15% to 25% of all older-community residents (ie, age 60 years and older), particularly those living in long-term care facilities. In recent years, marked progress has been made in the diagnosis and treatment of mood disorders in nursing home residents. In 1987, only 10% of nursing home residents were receiving antidepressant medication for clinical symptoms of mood disorders. By 1999, 25% of all residents were receiving antidepressants as a result of more comprehensive assessments and better diagnosis of mood disorders (Katz, Streim, Parmelee, & Datto, 2001).

Despite the high prevalence of major mood disorders in clients of all ages, these disorders are commonly under-diagnosed and under-treated by primary care and other non-psychiatric practitioners, the individuals who are most likely to see clients initially. For example, the incidence of a major mood disorder in primary care clients is approximately 10%, suggesting that clinical symptoms may go undiagnosed or untreated (Sadock & Sadock, 2003). In addition, the social stigma attached to mood disorders contributes to this rate of under-diagnosis and under-treatment. Clients may resist seeking treatment or the practitioner may be reluctant to formally diagnose mood disorders. In addition, poor adherence by clients to long-term treatment of a chronic mood disorder, and client reluctance to reveal the presence of a mood disorder when applying for a driver’s license, seeking employment, or seeking security clearance also plays a role in under-diagnosis and under-treatment.

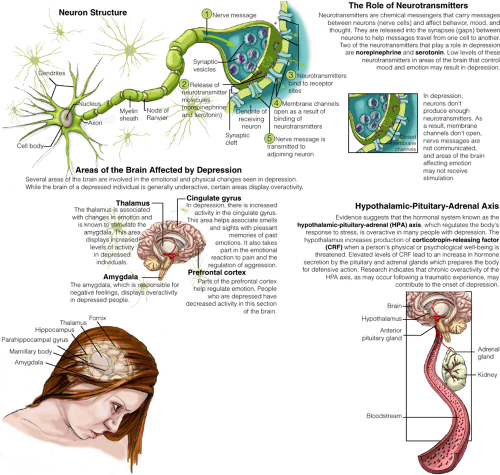

Despite the tendency to underestimate the importance and prevalence of mood disorders, their devastating effects on people’s work and personal lives are better understood now than they have been in the past. Researchers are exploring more fully the biologic basis of mood disorders, such as the role of neurotransmitters and neuroendocrine regulation. The data reported are most consistent with the hypothesis that mood disorders are associated with varied impairments

in the regulation of norepinephrine and serotonin (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

in the regulation of norepinephrine and serotonin (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

This chapter discusses the historical perspective of mood disorders, the theories of mood disorders, including the primary risk factors for developing mood disorders, and clinical symptoms and diagnostic characteristics of the major mood disorders diagnosed. Using the nursing process, the chapter presents information about important areas for assessment, and key intervention strategies when providing care for a client with a mood disorder.

Historical Perspective of Mood Disorders

Few disorders throughout history have been described with such consistency as mood disorders. Symptoms that characterize the disorders can be found in medical literature throughout the centuries from the ancient Greeks to the present era. As early as the 4th and 5th centuries BC, the term melancholia was used by ancient Greeks to describe the dark mood of depression. Hippocrates used the term melancholia to describe depression and mania to describe mental disturbances in clients. During the 2nd century AD, Arteaeus of Cappadocia described cyclothymia as a form of mental disease with alternating periods of depression and mania. For centuries, melancholia and cyclothymia were regarded to be separate disease entities rather than diverse expressions of mood disorders. By 1880, four categories of mood disorders existed: mania, melancholia, monomania, and dipsomania. In 1882, a German psychiatrist, Karl Kahlbaum described melancholia and mania as a continuum of the same illness. In 1899, Emil Kraepelin, another psychiatrist, reinforced Kahlbaum’s theory about the continuum of depression. Kraepelin introduced the category of manic-depressive psychosis, citing most of the criteria now used to establish the diagnosis of bipolar I disorder. He also introduced the category of involutional melancholia, now viewed as a mood disorder that occurs in late adulthood (Emental-health.com, 2005a, 2005b; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Etiology of Mood Disorders

In the past, causes of a mood disorder were classified as genetic, biochemical, and environmental. In addition, several medical illnesses are highly correlated with mood disorders. Moreover, individuals of any age may experience changes in mood or affect as an adverse effect of medication. However, older adults are more likely than younger adults to experience medication-related mood disorders. Risk factors for the development of mood disorders have been identified as clinical practice guidelines for primary care practitioners. These are highlighted in Box 21-1. In addition, several theories about mood disorders have been postulated.

Box 21.1: Risk Factors for Mood Disorders

The following risk factors for mood disorders have been established as clinical practice guidelines for primary care practitioners.

Prior episodes of depression

Family history of depressive disorders

Prior suicide attempts

Female gender

Age of onset younger than 40 years

Postpartum period

Medical comorbidity associated with a high risk of depression

Lack of social support

Stressful life events

Current alcohol or substance abuse or use of medication associated with a high risk of depression

Presence of anxiety, eating disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, somatization disorder, personality disorder, grief, adjustment reactions. Depression may coexist with other psychiatric conditions.

Genetic Theory

According to statistics from the National Institute of Mental Health (2005), studies involving adoptees revealed higher correlations of mood disorders between depressed adoptees and biologic parents than adoptive parents. Studies of twins have shown that if an identical twin develops a mood disorder, the other twin has a 70% chance of developing the disorder, too. The risk decreases to about 15% with siblings, parents, or children of the person with the mood disorder. Grandparents, aunts, or uncles have about a 7% chance of developing a mood disorder.

Theorists believe that a dominant gene may influence or predispose a person to react more readily to experiences of loss or grief, thus manifesting symptoms

of a mood disorder. For example, Medina (1995) discusses the history of BPD (previously referred to as manic-depressive disorder) research since 1987. He cites the various pseudogenetic studies dealing with the linkage between human genes and human behaviors. “No gene for bipolar disorder has been isolated….There is strong disagreement as to the number of genes actually involved in the disease. The ups and downs of the published literature illustrate the enormous problems researchers encounter attempting to describe human behavior in terms of genetic sequence” (p. 30).

of a mood disorder. For example, Medina (1995) discusses the history of BPD (previously referred to as manic-depressive disorder) research since 1987. He cites the various pseudogenetic studies dealing with the linkage between human genes and human behaviors. “No gene for bipolar disorder has been isolated….There is strong disagreement as to the number of genes actually involved in the disease. The ups and downs of the published literature illustrate the enormous problems researchers encounter attempting to describe human behavior in terms of genetic sequence” (p. 30).

Biochemical Theory

Biogenic amines, or chemical compounds known as norepinephrine and serotonin, have been shown to regulate mood and to control drives such as hunger, sex, and thirst. Increased amounts of these neurotransmitters at receptor sites in the brain cause an elevation in mood, whereas decreased amounts can lead to depression. Although norepinephrine and serotonin are the biogenic amines most often associated with the development of a mood disorder, dopamine has also been theorized to play a role (Figure 21-1). As with norepinephrine and serotonin, dopamine activity may be reduced in depressed mood and increased in mania, the two phases of BPD. These explanations are termed the biogenic amine hypothesis (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Neuroendocrine Regulation

High levels of the hormone cortisol have been observed in persons with clinical symptoms of a mood disorder. Normally, cortisol levels peak in the early morning, level off during the day, and reach the lowest point in the evening. Cortisol peaks earlier in persons with a depressed mood and remains high all day.

Mood is also affected by the thyroid gland. Approximately 5% to 10% of clients with abnormally low levels of thyroid hormones may suffer from a chronic mood disorder. Clients with a mild, symptom-free form of hypothyroidism may be more vulnerable to depressed mood than the average person (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Research studies continue to focus on neuroendocrine abnormalities described in clients with mood disorders. These abnormalities include decreased nocturnal secretion of melatonin; decreased levels of prolactin, follicle-stimulating hormone, testosterone, and somatostatin; and sleep-induced stimulation of growth hormone (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Biologic Theory

It has long been believed that there is a biologic relationship between various medical conditions (eg, pain or cardiovascular disease in women) and depression. Following is a brief summary of theories regarding the biologic connections between depression and certain medical conditions.

Neurodegenerative Diseases

A variety of neurodegenerative diseases are associated with depressive manifestations. Depression is the most common psychiatric symptom encountered in clients who have Alzheimer’s disease, affecting approximately 25% to 50% of the clients. The relationship between dementia and depression is complex. Some clients become depressed because they are aware of the prognosis of their diagnosis; whereas other clients are depressed due to degenerative changes in the neural system. Depression is also estimated to afflict 40% to 50% of individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Postmortem examinations have revealed low levels of norepinephrine and serotonin due to degeneration of both frontocortical circuits and the brainstem regions. Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a third neurodegenerative disorder commonly associated with depressive symptoms. Degenerative effects of widespread areas of the brain, as in stroke, are believed to be the cause of neuropsychiatric symptoms. Various studies have indicated that approximately 25.7 % of clients with MS had the diagnosis of major depression; 30% of individuals studied had contemplated suicide; and more than 6% had attempted suicide (Feinstein, 2002; Patten, Beck, & Williams, 2003).

Immunotherapy

Depression is linked biologically to the use of immunotherapeutic agents in the treatment of certain diseases. Research by Dantzer and Kelley revealed that about one third of clients who receive cytokine therapy develop depression. Symptoms of depression began within days to weeks of therapy and disappeared when the treatment ended (Stong, 2004).

Pancreatic tumors release high levels of cytokine. Research findings revealed that clients with pancreatic tumors exhibited clinical symptoms of depression whereas other cancer clients were not depressed. Additionally, cancer drugs such as procarbazine inhibit dopamine beta-hydroxylase, while vincristine and vinblastine decrease conversion of dopamine to

norepinephrine. Higher depression rates have also been reported in clients who receive tamoxifen and interferon-alpha (MacNeil, 2005).

norepinephrine. Higher depression rates have also been reported in clients who receive tamoxifen and interferon-alpha (MacNeil, 2005).

Medical Conditions

Studies describe the relationship between depression and certain medical conditions. In clients with chronic inflammation, such as occurs with coronary heart disease or type 2 diabetes mellitus, the prevalence of depression increases between 12% and 30% (Stong, 2004). Hypotheses vary regarding the physiologic basis for the higher incidence of depression in people with diabetes. Barden (2004) discusses the implication of increased activity within the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis as one characteristic of depression. Such activity has also been seen as a factor in maintaining glycemic balance. The effects of the

increased HPA activity in both diabetes and depression may partly explain the link between the two. Box 21-2 lists medications and medical illnesses that are highly correlated with the development of depression.

increased HPA activity in both diabetes and depression may partly explain the link between the two. Box 21-2 lists medications and medical illnesses that are highly correlated with the development of depression.

Box 21.2: Medications and Medical Illnesses Correlated With Depression

Medications

Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: opioids, ibuprofen, and indomethacin

Antimicrobials: sulfonamides and isoniazide

Antineoplastic agents: asparaginase and tamoxifen

Antiparkinson agents: levodopa and amantadine

Cardiac medications and antihypertensives: digoxin, procainamide, reserpine, propranolol, methyldopa, clonidine, guanethidine, and hydralazine

Central nervous system agents: alcohol, benzodiazepines, meprobamate, flurazepam, haloperidol, barbiturates, and fluphenazine

Histamine blockers: cimetidine and ranitidine

Hormonal agents: corticosteroids, estrogen, and progesterone

Medical Illnesses

Central nervous system: Parkinson’s disease, strokes, tumors, hematoma, neurosyphilis, and normal pressure hydrocephalus

Nutritional deficiencies: folate or B12, pernicious anemia, and iron deficiency

Cardiovascular disturbances: congestive heart failure and subacute bacterial endocarditis

Metabolic and endocrine disorders: diabetes, hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism, hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia, parathyroid disorders, adrenal diseases, hepatic or renal disease and premenstrual syndrome

Fluid and electrolyte disturbances: hypercalcemia, hypokalemia, and hyponatremia

Infections: meningitis, viral pneumonia, hepatitis, and urinary tract infections

Miscellaneous: rheumatoid arthritis, cancer (particularly of the pancreas or intestinal tract), tuberculosis, tertiary syphilis, and fibromyalgia

Pain

The association between depression and pain is very high. It has been hypothesized that not all pain is linked to an identifiable medical condition such as arthritis or fibromyalgia, but rather it can be biologic in origin (eg, undetected cellular changes) and create a vicious circle in which the pain leads to psychomotor agitation, agitation leads to irritability, irritability leads to aggression, and aggression leads to depression and more pain, often resulting in disability (Finn, 2004).

Psychodynamic Theory

The psychodynamic theory of depression, based on the work of Sigmund Freud, Karl Abraham, Melanie Klein, and others, begins with the observation that bereavement normally produces symptoms resembling a mood disorder. That is, people with a depressed mood are like mourners who do not make a realistic adjustment to living without the loved person. In childhood, they are bereft of a parent or other loved person, usually the result of the absence or withdrawal of affection. Any loss or disappointment later in life reactivates a delayed grief reaction that is accompanied by self criticism, guilt, and anger turned inward. Because the source and object of the grief are unconscious (from childhood), symptoms are not resolved, but rather persist and return later in life (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Additionally, several theorists, such as Karl Abraham, Bertram Lewin, and Melanie Klein, have attempted to explain the psychodynamic factors of mania. Manic episodes are viewed as a defense reaction against underlying depression due to the client’s inability to tolerate a developmental tragedy, such as the loss of a parent. These episodes also may be the result of a tyrannical superego, producing intolerable self-criticism that is replaced by euphoric self-satisfaction, or an ego overwhelmed by pleasurable impulses such as sex or by feared impulses such as aggression (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Behavioral Theory: Learned Helplessness

Behavioral theorists regard mood disorders as a form of acquired or learned behavior. For one reason or

another, people who receive little positive reinforcement for their activity become withdrawn, overwhelmed, and passive, giving up hope and shunning responsibility. This, in turn, leads to a perception that things are beyond their control. This perception promotes feelings of helplessness and hopelessness, both hallmarks of depressed states. Behaviorists who subscribe to this theory believe that a client’s depressed mood could improve if the client develops a sense of control and mastery of the environment (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

another, people who receive little positive reinforcement for their activity become withdrawn, overwhelmed, and passive, giving up hope and shunning responsibility. This, in turn, leads to a perception that things are beyond their control. This perception promotes feelings of helplessness and hopelessness, both hallmarks of depressed states. Behaviorists who subscribe to this theory believe that a client’s depressed mood could improve if the client develops a sense of control and mastery of the environment (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Cognitive Theory

Cognitive or cognitive-behavioral theorists believe that thoughts are maintained by reinforcement, thus contributing to a mood disorder. People with a depressed mood are convinced that they are worthless, that the world is hostile, that the future offers no hope, and that every accidental misfortune is a judgment of them. Such reactions are the result of assumptions learned early in life and brought into play by disappointment, loss, or rejection. For example, a young child may be told by one parent that the child is not athletic enough to play basketball in grade school. As the child approaches high school, he may assume that he lacks talent and, although he would like to play basketball, he does not try out for the team. Cognitive distortions or self-defeating thoughts become part of a destructive cycle in which the individual exhibits apathy, sadness, and social withdrawal (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Life Events and Environmental Theory

Complex etiology based on interacting contributions from life events and the environment may ultimately result in clinical symptoms of depression. For example, stressful life events such as the loss of a parent or spouse, financial hardship, illness, perceived or real failure, and midlife crises are all examples of factors contributing to the development of a mood disorder. Certain populations of people including the poor, single persons, or working mothers with young children seem to be more susceptible than others to stressful events and the development of mood disorders. The life event most often associated with the development of a mood disorder is the loss of a parent before the age of 11 years. The environmental stressor most often associated with an episode of depressed mood is loss of a spouse. Additionally, dramatic changes in one’s life can trigger depressive episodes. For instance, relocation, loss or change of employment, and retirement can all produce symptoms that may or may not be temporary. Some theorists believe that early life events such as abuse and neglect experienced by a client results in a long-lasting change in the brain’s biology, affecting the functional states of neurotransmitters and intraneuronal signaling systems (Gillespie & Nemeroff, 2005; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Clinical Symptoms and Diagnostic Characteristics of Depressive Disorders

The clinical symptoms of depressive disorders, one of the two major types of mood disorders, have been categorized in many ways. One method is by placing depressive behaviors on a continuum from mild or transitory depression to severe depression. Mild depression is exhibited by affective symptoms of sadness or “the blues”—an appropriate response to stress. The person who experiences such depression may be less responsive to the environment and may complain of physical discomfort. However, the person usually recovers within a short period. For example, a person may become disappointed when told that he or she was not chosen as a representative to a conference that the person hoped to attend. During this time, the person may be unable to concentrate, may communicate less with coworkers, may appear less productive than normal, and may isolate him- or herself at work and at home.

Clinical symptoms of moderate depression (dysthymia) are less severe than those experienced in a major depressive disorder and do not include psychotic features; e.g., individuals with dysthymia usually complain that they have always been depressed. They verbalize feelings of guilt, inadequacy, and irritability. They exhibit a lack of interest and lack of productivity. Persons with severe depression exhibit psychotic symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations.

Major depressive disorders are referred to as endogenous depression when the depressed mood appears to develop from within a client, and no apparent cause or external precipitating factor is identified. Depression caused by a biochemical imbalance is such an example.

Clinical Symptoms and Diagnostic Characteristics/Major Depressive Disorder

Clinical Symptoms

Depressed mood

Significant loss of interest or pleasure

Marked changes in weight or significant increase or decrease in appetite

Insomnia or hypersomnia

Psychomotor agitation or retardation

Fatigue or loss of energy

Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt

Reduced ability to concentrate or think, or indecisiveness

Recurrent thoughts of death, suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, or plan for committing suicide

Diagnostic Characteristics

Evidence of at least five clinical symptoms in conjunction with depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure

Symptoms occurring most of the day and nearly every day during the same 2-week period representing an actual change in person’s previous level of functioning

Significant distress or marked impairment in person’s functioning, such as in social or occupational areas

Symptoms not related to a medical condition or use of a substance

The DSM-IV-TR categorizes depressive disorders as major depressive disorder; dysthymic disorder; and depressive disorder, not otherwise specified (NOS). The DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for prepubertal, adolescent, and adult depression are identical. Information regarding childhood and adolescent depression is provided in Chapter 29. Late-life depression is discussed in Chapter 30.

Major Depressive Disorder

According to NIMH (2005) major depressive disorder has been identified as the fourth leading cause of worldwide disease in 1990, causing more disability than either ischemic heart disease or cerebral vascular disease. According to the DSM-IV-TR, persons with a major depressive disorder do not experience momentary shifts from one unpleasant mood to another. During a 2-week period, the individual exhibits five or more of the nine clinical symptoms of a major depressive episode in conjunction with a depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure (see the accompanying Clinical Symptoms and Diagnostic Characteristics box). The clinical symptoms interfere with social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. Symptoms are not due to effects of a substance, nor are they caused by a general medical condition. See Clinical Example 21-1.

Clinical Example 21.1: The Client With Major Depressive Disorder

AS, a 25-year-old professional basketball player, complained of fatigue during practice. He had a few episodes of vertigo the previous week and also stated that he could not remember the different plays the coach recently designed. The team physician examined AS. During the examination, AS revealed that he did not enjoy playing basketball anymore, had no interest in socializing with his peers or fiancée, and felt as if he “didn’t belong” or fit in with other members of the team. The physician noted that despite no physiologic reason for a weight loss, AS had lost 15 pounds since his last physical examination. AS described a lack of appetite for approximately 2 weeks. The team physician was able to determine that AS was exhibiting clinical symptoms of major depressive disorder without psychotic features or suicidal ideation and subsequently prescribed an antidepressant medication and supportive psychotherapy.

Major depressive disorder may be coded as mild, moderate, or severe; with or without psychotic features; and as in partial or full remission. Reference also is made to identify it as a single or recurrent episode. The specifier “with seasonal pattern” can be applied to the pattern of major depressive episodes if the clinical symptoms occur at characteristic times of the year. For example, most episodes begin in fall or winter and

remit in the spring, although some clients experience it during the summer. Clinicians often refer to this type of mood disorder with seasonal pattern as seasonal affective disorder (SAD). The prevalence of SAD is approximately 7.8% of the U.S. population. This disorder is nearly twice as prevalent in women (10.4%) as in men (5.3%) and usually occurs in women between the ages of 20 and 40 years. Individuals who live in areas where seasonal changes occur are more prone to the development of SAD (eg, Vermont, 16%; Montana, 14%; and North Dakota, 14%). The prevalence of SAD across southern states is approximately 6.7%, suggesting that it is relatively common in the southern U.S. (Stong, 2005).

remit in the spring, although some clients experience it during the summer. Clinicians often refer to this type of mood disorder with seasonal pattern as seasonal affective disorder (SAD). The prevalence of SAD is approximately 7.8% of the U.S. population. This disorder is nearly twice as prevalent in women (10.4%) as in men (5.3%) and usually occurs in women between the ages of 20 and 40 years. Individuals who live in areas where seasonal changes occur are more prone to the development of SAD (eg, Vermont, 16%; Montana, 14%; and North Dakota, 14%). The prevalence of SAD across southern states is approximately 6.7%, suggesting that it is relatively common in the southern U.S. (Stong, 2005).

Dysthymic Disorder

The client with the diagnosis of dysthymic disorder typically exhibits symptoms that are similar to those of major depressive disorder or severe depression. However, they are not as severe and do not include symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations, impaired communication, or incoherence. Clinical symptoms usually persist for 2 years or more and may occur continuously or intermittently with normal mood swings for a few days or weeks. Persons who develop dysthymic disorder are usually overly sensitive, often have intense guilt feelings, and may experience chronic anxiety. Dysthymic disorder affects approximately 5.4% of the U.S. population age 18 years and older (or 10.9 million adults) during their lifetime. Dysthymic disorder often begins in childhood, adolescence, or early adulthood (NIMH, 2005).

According to DSM-IV-TR criteria, the individual, while depressed, must exhibit two or more of six clinical symptoms of a major depressive episode, including poor appetite or overeating, insomnia or hypersomnia, low energy or fatigue, low self-esteem, poor concentration or difficulty making decisions, and feelings of hopelessness. Clinical symptoms interfere with functioning and are not caused by a medical condition or the physiologic effects of a substance.

Depressive Disorder, Not Otherwise Specified

The diagnosis of depressive disorder, NOS, is used to identify disorders with depressive features that do not meet the criteria for major depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder, adjustment disorder with depressed mood, or adjustment disorder with mixed anxiety and depressed mood (see Chapter 29 for more information on adjustment disorders).

Clinical Symptoms and Diagnostic Characteristics of Bipolar Disorder

Various descriptive terms are used to describe the labile affect or mood changes of clients with the diagnosis of bipolar disorder. These terms include:

Euphoria, an exaggerated feeling of physical and emotional well-being

Elation, a state of extreme happiness, delight, or excitability

Hypomania, a psychopathological state and abnormality of mood falling somewhere between normal euphoria and mania, characterized by unrealistic optimism, pressure of speech and activity, and a decreased need for sleep (some clients show an increase in creativity during hypomanic states, whereas others show poor judgment, irritability, and irascibility). Individuals with hypomania are able to function socially, academically, and occupationally although their behavior is significantly different from their baseline.

Mania, a state characterized by excessive elation, inflated self-esteem, and grandiosity

Rapid-cycling, a state characterized by the occurrence of four or more mood episodes during the previous 12 months; a course modifier for the differential diagnosis of BPD

These changes may be placed on a continuum, from mild to severe, the same as those of depressive behaviors.

The client with mania generally exhibits hyperactivity, agitation, irritability, and accelerated thinking and speaking. Behaviors may include pathological gambling, a tendency to disrobe in public places, wearing excessive attire and jewelry of bright colors in unusual combinations, and inattention to detail (Figure 21-2). The client may be preoccupied with religious, sexual, financial, political, or persecutory thoughts that can develop into complex delusional systems. Flight of ideas, as well as other psychotic symptoms discussed in Chapter 9, may persist (Sadock & Sadock, 2003; Shahrokh & Hales, 2003).

BPD is generally underdiagnosed because of under-recognition of manic and hypomanic episodes. The complex nature of BPD makes an accurate differential

diagnosis a challenge, even for experienced clinicians. Although many clients present to a health care provider within 1 year of symptom onset, there is usually a 5- to 10-year delay from symptom onset to formal diagnosis. Many clients report that they have not been correctly diagnosed until they were seen by three or more health care professionals (St. John, 2005).

diagnosis a challenge, even for experienced clinicians. Although many clients present to a health care provider within 1 year of symptom onset, there is usually a 5- to 10-year delay from symptom onset to formal diagnosis. Many clients report that they have not been correctly diagnosed until they were seen by three or more health care professionals (St. John, 2005).

As noted earlier, BPD affects approximately 2.3 million American adults (or about 1.2%) age 18 years and older in a given year. Men and women are equally likely to develop BPD. The average age of onset is in the early twenties (NIMH, 2005). The clinical presentation of BPD in children and adolescents is often different from that seen in adults. Moods in children and adolescents tend to be more irritable than euphoric. In addition, adolescents often have greater difficulty with mood liability, explosive outbursts of anger followed by remorse, and prolonged emotional response to stimuli. They often perform poorly academically and exhibit abrupt switches between good and bad behavior. Mania in adolescents is commonly misdiagnosed as antisocial personality disorder (see Chapter 24) or schizophrenia (see Chapter 22). Although BPD is less common with increasing age, the first episode can occur in older adults. The estimated prevalence of mania in elders is 5% to 19%. The mortality rate for untreated BPD is higher than for most types of heart disease and some types of cancer (St. John, 2005).

The category of BPD includes bipolar I disorder; bipolar II disorder; cyclothymic disorder; and BPD, NOS. BPD, NOS, is used to code disorders with features of BPD when these features do not meet the criteria for any specific BPD. Bipolar I, bipolar II, and cyclothymic disorders are discussed in the following sections.

Bipolar I Disorder

Bipolar I disorder occurs less commonly than major depressive disorder with a lifetime prevalence of about 1%, similar to the statistics for schizophrenia (Sadock & Sadock, 2003). It is characterized by one or more manic or mixed episodes in which the individual experiences rapidly alternating moods accompanied by symptoms of a manic mood and a major depressive episode. The specifier single manic episode is used when a client experiences the first manic episode. The specifier recurrent episode

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access