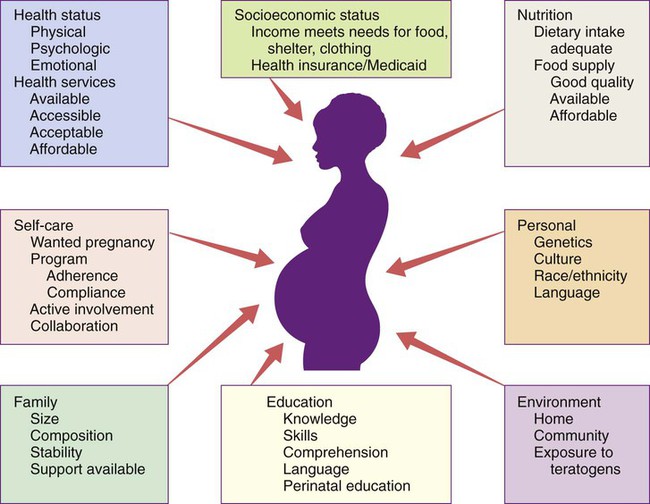

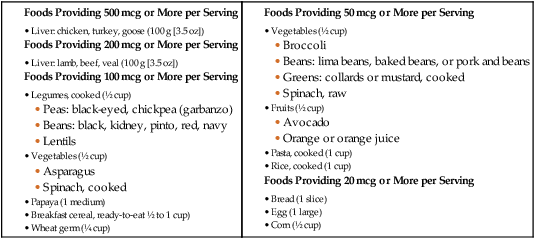

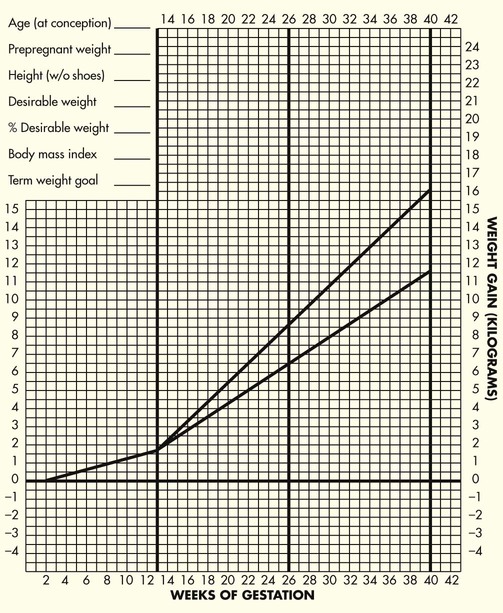

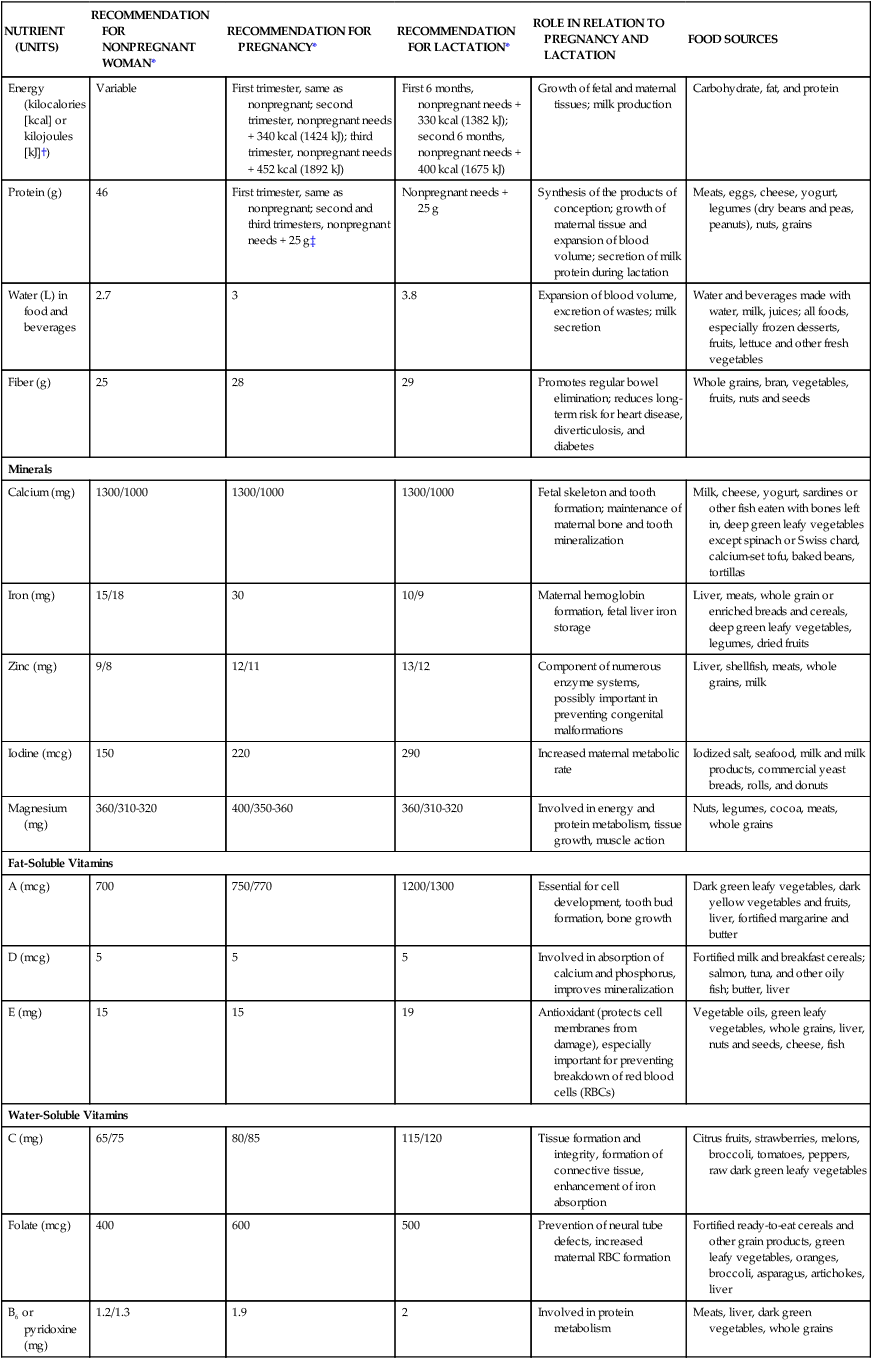

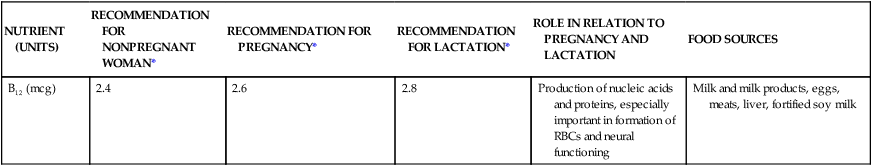

Chapter 9 On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Explain recommended maternal weight gain during pregnancy. • Compare the recommended level of intake of energy sources, protein, and key vitamins and minerals during pregnancy and lactation. • Give examples of the food sources that provide the nutrients required for optimal maternal nutrition during pregnancy and lactation. • Examine the role of nutrition supplements during pregnancy. • List five nutritional risk factors during pregnancy. • Compare the dietary needs of adolescent and mature pregnant women. • Analyze examples of eating patterns of women from two different ethnic or cultural backgrounds and identify potential dietary problems. Nutrition is one of the many factors that influence the outcome of pregnancy (Fig. 9-1). However, maternal nutritional status is an especially significant factor, both because it is potentially alterable and because good nutrition before and during pregnancy is an important preventive measure for a variety of problems. These problems include birth of low-birth-weight (LBW) (birth weight of 2500 g or less) and preterm infants. Evidence is growing that a mother’s nutrition and lifestyle affect the long-term health of her children. Thus the importance of good nutrition must be emphasized to all women of childbearing potential. Key components of nutrition care during the preconception period and pregnancy include (Harnisch, Harnisch, and Harnisch, 2012): • Nutrition assessment that includes appropriate weight for height and adequacy and quality of dietary intake and habits • Diagnosis of nutrition-related problems or risk factors such as diabetes, phenylketonuria (PKU), and obesity • Intervention based on an individual’s dietary goals and plan to promote appropriate weight gain, ingestion of a variety of foods, appropriate use of dietary supplements, and physical activity • Evaluation as an integral part of the nursing care provided to women during the preconception period and pregnancy, with referral to a nutritionist or dietitian as necessary The first trimester of pregnancy is a crucial one in terms of embryonic and fetal organ development. A healthful diet before conception is the best way to ensure that adequate nutrients are available for the developing fetus. Folate or folic acid intake is of particular concern in the periconception period. Folate is the form in which this vitamin is found naturally in foods, and folic acid is the form used in fortification of grain products and other foods and in vitamin supplements. Neural tube defects (failure in closure of the neural tube) are more common in infants of women with poor folic acid intake. Proper closure of the neural tube is required for normal formation of the spinal cord, and the neural tube begins to close within the first month of gestation, often before the woman realizes that she is pregnant (Box 9-1). • The uterine-placental-fetal unit. • Maternal blood volume and constituents: During pregnancy the total blood volume increases by about 40% to 50% over normal. The plasma volume increases by 50% in women in their first pregnancies and more than this in multifetal pregnancies. Although red blood cell (RBC) production also is stimulated, the expansion of RBC mass is not as great as that of plasma volume. Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) (www.iom.edu) have been established for the people of the United States and Canada and are updated regularly. The DRIs include recommendations for daily nutritional intakes that meet the needs of almost all (97% to 98%) of the healthy members of the population. They are divided into age, sex, and life-stage categories (e.g., infancy, pregnancy, and lactation), and they can be used as goals in planning the diets of individuals (Table 9-1). TABLE 9-1 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR DAILY INTAKES OF SELECTED NUTRIENTS DURING PREGNANCY AND LACTATION *When two values appear, separated by a diagonal slash, the first is for females younger than 19 years and the second is for those 19 to 50 years of age. †The international metric unit of energy measurement is the joule (J). 1 kcal = 4.184 kJ. ‡Add an additional 25 g in twin pregnancies. Data from Otten JJ, Helwig JP, Meyers LD, editors: Dietary reference intakes: the essential guide to nutrient requirements, Washington, DC, 2006, National Academies Press. in which the weight is in kilograms and height is in meters. Thus for a woman who weighed 51 kg before pregnancy and is 1.57 m tall: Prepregnant BMI can be classified into the following categories: less than 18.5, underweight or low; 18.5 to 24.9, normal; 25 to 29.9, overweight or high; and greater than 30, obese (www.nhlbisupport.com/bmi). The BMI can be calculated on this website (see also Box 3-6). For women with single fetuses, current recommendations are that women with normal BMI should gain 11.5 to 16 kg (25 to 35 lbs) during pregnancy (Fig. 9-2). Box 9-2 lists recommended weight gain for pregnancies with single fetuses, twin gestations, and multifetal (more than 2) gestations for women who are normal weight, underweight, and overweight. The recommended energy (kcal) intake corresponds to the recommended pattern of gain (see Table 9-1). There is no increment for the first trimester; an additional 340 kcal per day and 462 kcal per day over the prepregnant intake is recommended during the second and third trimester, respectively. These recommendations are most appropriate for singleton pregnancy and may need to be adjusted in multiple gestation. The amount of food providing the needed increase in energy is not large. The 340 additional kcal needed during the second trimester can be provided by one additional serving from any one of the following groups: milk, yogurt, or cheese (all skim milk products); fruits; vegetables; and bread, cereal, rice, or pasta. In the third trimester, an additional one third of a serving will provide the needed kcal. An obsession with thinness and dieting pervades the North American culture. Figure-conscious women may find it difficult to make the transition from guarding against weight gain before pregnancy to valuing weight gain during pregnancy. In counseling these women, the nurse can emphasize the positive effects of good nutrition as well as the adverse effects of maternal malnutrition (manifested by poor weight gain) on infant growth and development. This counseling includes information on the components of weight gain during pregnancy (Table 9-2) and the amount of this weight that will be lost at birth. Because lactation can help reduce maternal energy stores gradually, this also provides an opportunity to promote breastfeeding. TABLE 9-2 TISSUES CONTRIBUTING TO MATERNAL WEIGHT GAIN AT 40 WEEKS OF GESTATION In the United States, 20% of women who give birth are obese (www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/MaternalInfantHealth/PregComplications.htm). Pregnancy is not a time for a weight-reduction diet. Even overweight or obese pregnant women need to gain at least enough weight to equal the weight of the products of conception (fetus, placenta, and amniotic fluid). If they limit their energy intake to prevent weight gain, they may also excessively limit their intake of important nutrients. Moreover, dietary restriction results in catabolism of fat stores, which in turn augments the production of ketones. The long-term effects of mild ketonemia during pregnancy are not known, but ketonuria is associated with the occurrence of preterm labor. It should be stressed to obese women (and to all pregnant women) that the quality of the weight gain is important, with emphasis placed on the consumption of nutrient-dense foods and the avoidance of empty-calorie foods (see Critical Thinking Case Study). Weight gain is important, but pregnancy is not an excuse for uncontrolled dietary indulgence. The woman should place an emphasis on the quality of her food intake as she considers her needs and those of her fetus. Excessive weight gained during pregnancy may be difficult to lose after pregnancy, thus contributing to chronic overweight or obesity—an etiologic factor in a host of chronic diseases, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and arteriosclerotic heart disease. The woman who gains 18 kg or more is especially at risk (Box 9-3). Food energy intake and particularly intake of fat is likely to be high among pregnant women, especially low-income women (see Evidence-Based Practice box). • The rapid growth of the fetus • The enlargement of the uterus and its supporting structures, the mammary glands, and the placenta • The increase in the maternal circulating blood volume and the subsequent demand for increased amounts of plasma protein to maintain colloidal osmotic pressure Milk, meat, eggs, and cheese are complete protein foods with a high biologic value. Legumes (dried beans and peas), whole grains, and nuts are also valuable sources of protein. In addition, these protein-rich foods are a source of other nutrients such as calcium, iron, and B vitamins. Plant sources of protein often provide needed dietary fiber. The recommended daily food plan (Table 9-3) is a guide to the amounts of these foods that would supply the quantities of protein needed. The recommendations provide for only a modest increase in protein intake (25 g daily) over the prepregnant levels in adult women. TABLE 9-3 DAILY FOOD GUIDE FOR PREGNANCY AND LACTATION *These are approximate amounts based on a relatively sedentary lifestyle and should be individualized. Intake may have to be increased for women with a more active lifestyle or multiple gestation, those who are underweight before pregnancy, or those exhibiting poor gestational weight gain. Needs during lactation may also be greater than these recommendations. †Beans are also part of the vegetable group; avocados are also part of the fruit group, and nuts and seeds are part of the meat and beans group. The safety of caffeine use in pregnancy is an important consideration. Some investigators (e.g., Weng, Odouli, and Li, 2008) but not others (e.g., Pollack, Louis, Sundaram, et al., 2010) found that women who consume more than 200 mg of caffeine daily (equivalent to about 12 oz of coffee) may be at increased risk for miscarriage. Data also suggest that excess caffeine intake may contribute to IUGR. In their review, Jahanfar and Sharifah (2009) found that there is insufficient evidence to determine whether caffeine has any effect on pregnancy outcome. Although the evidence about caffeine is far from conclusive, the March of Dimes recommends a daily intake of no more than 200 mg of caffeine (March of Dimes, 2010). Caffeine is found not only in coffee but also in tea, some soft drinks, and chocolate (Table 9-4). TABLE 9-4 CAFFEINE CONTENT OF COMMON BEVERAGES AND FOODS

Maternal and Fetal Nutrition

Nutrient Needs before Conception

Nutrient Needs during Pregnancy

NUTRIENT (UNITS)

RECOMMENDATION FOR NONPREGNANT WOMAN*

RECOMMENDATION FOR PREGNANCY*

RECOMMENDATION FOR LACTATION*

ROLE IN RELATION TO PREGNANCY AND LACTATION

FOOD SOURCES

Energy (kilocalories [kcal] or kilojoules [kJ]†)

Variable

First trimester, same as nonpregnant; second trimester, nonpregnant needs + 340 kcal (1424 kJ); third trimester, nonpregnant needs + 452 kcal (1892 kJ)

First 6 months, nonpregnant needs + 330 kcal (1382 kJ); second 6 months, nonpregnant needs + 400 kcal (1675 kJ)

Growth of fetal and maternal tissues; milk production

Carbohydrate, fat, and protein

Protein (g)

46

First trimester, same as nonpregnant; second and third trimesters, nonpregnant needs + 25 g‡

Nonpregnant needs + 25 g

Synthesis of the products of conception; growth of maternal tissue and expansion of blood volume; secretion of milk protein during lactation

Meats, eggs, cheese, yogurt, legumes (dry beans and peas, peanuts), nuts, grains

Water (L) in food and beverages

2.7

3

3.8

Expansion of blood volume, excretion of wastes; milk secretion

Water and beverages made with water, milk, juices; all foods, especially frozen desserts, fruits, lettuce and other fresh vegetables

Fiber (g)

25

28

29

Promotes regular bowel elimination; reduces long-term risk for heart disease, diverticulosis, and diabetes

Whole grains, bran, vegetables, fruits, nuts and seeds

Minerals

Calcium (mg)

1300/1000

1300/1000

1300/1000

Fetal skeleton and tooth formation; maintenance of maternal bone and tooth mineralization

Milk, cheese, yogurt, sardines or other fish eaten with bones left in, deep green leafy vegetables except spinach or Swiss chard, calcium-set tofu, baked beans, tortillas

Iron (mg)

15/18

30

10/9

Maternal hemoglobin formation, fetal liver iron storage

Liver, meats, whole grain or enriched breads and cereals, deep green leafy vegetables, legumes, dried fruits

Zinc (mg)

9/8

12/11

13/12

Component of numerous enzyme systems, possibly important in preventing congenital malformations

Liver, shellfish, meats, whole grains, milk

Iodine (mcg)

150

220

290

Increased maternal metabolic rate

Iodized salt, seafood, milk and milk products, commercial yeast breads, rolls, and donuts

Magnesium (mg)

360/310-320

400/350-360

360/310-320

Involved in energy and protein metabolism, tissue growth, muscle action

Nuts, legumes, cocoa, meats, whole grains

Fat-Soluble Vitamins

A (mcg)

700

750/770

1200/1300

Essential for cell development, tooth bud formation, bone growth

Dark green leafy vegetables, dark yellow vegetables and fruits, liver, fortified margarine and butter

D (mcg)

5

5

5

Involved in absorption of calcium and phosphorus, improves mineralization

Fortified milk and breakfast cereals; salmon, tuna, and other oily fish; butter, liver

E (mg)

15

15

19

Antioxidant (protects cell membranes from damage), especially important for preventing breakdown of red blood cells (RBCs)

Vegetable oils, green leafy vegetables, whole grains, liver, nuts and seeds, cheese, fish

Water-Soluble Vitamins

C (mg)

65/75

80/85

115/120

Tissue formation and integrity, formation of connective tissue, enhancement of iron absorption

Citrus fruits, strawberries, melons, broccoli, tomatoes, peppers, raw dark green leafy vegetables

Folate (mcg)

400

600

500

Prevention of neural tube defects, increased maternal RBC formation

Fortified ready-to-eat cereals and other grain products, green leafy vegetables, oranges, broccoli, asparagus, artichokes, liver

B6 or pyridoxine (mg)

1.2/1.3

1.9

2

Involved in protein metabolism

Meats, liver, dark green vegetables, whole grains

B12 (mcg)

2.4

2.6

2.8

Production of nucleic acids and proteins, especially important in formation of RBCs and neural functioning

Milk and milk products, eggs, meats, liver, fortified soy milk

Energy Needs

Weight Gain

Pattern of Weight Gain

Hazards of Restricting Adequate Weight Gain

TISSUE

KILOGRAMS

POUNDS

Fetus

3.2-3.9

7-8.5

Placenta

0.9-1.1

2-2.5

Amniotic fluid

0.9

2

Increase in uterine tissue

0.9

2

Breast tissue

0.5-1.8

1-4

Increased blood volume

1.8-2.3

4-5

Increased tissue fluid

1.4-2.3

3-5

Increased stores (fat)

1.8-2.7

4-6

Excessive Weight Gain

Protein

FOOD GROUP

DAILY AMOUNT OF FOOD RECOMMENDED FOR WOMEN*

SERVING SIZE

Grains

6- to 8-ounce equivalents

At least half of grain servings should be whole grains. Whole grains are those that contain the entire grain kernel (bran, germ, endosperm) (e.g., whole wheat or cornmeal, oatmeal, and brown rice).

Refined grains have been milled to remove the bran and germ (e.g., white flour, white bread, degermed cornmeal, white rice, and corn or flour tortillas).

1-ounce equivalent = 1 slice bread, 1 cup ready-to-eat cereal, or ½ cup cooked rice or pasta or cooked cereal

Vegetables

Vary the vegetables consumed to take advantage of the different nutrients they offer

2½ to 3 cups

Weekly intake should include at least the following: 3 cups dark green vegetables (e.g., spinach or greens, broccoli, bok choy, romaine lettuce); 2 cups orange vegetables (e.g., carrots; acorn, butternut, or Hubbard squash; sweet potatoes); 3 cups dry beans or peas (e.g., black, navy, or kidney beans; chickpeas; black-eyed peas; split peas; lentils; soybeans; tofu); 3 cups starchy vegetables (corn, green peas, potatoes); and 6½ cups of other vegetables (e.g., artichokes, asparagus, bean sprouts, green beans, cauliflower, cucumber, tomatoes, iceberg or head lettuce).

1 cup = 2 cups raw leafy greens; 1 cup of other vegetables, raw or cooked; or 1 cup of vegetable juice

Fruits

2 cups

1 cup = 1 cup raw, frozen, or canned fruit; 1 cup 100% juice; or ½ cup dried fruit

Milk, yogurt, and cheese (milk group)

3 cups

Most milk group choices should be fat free or low fat.

1 cup = 1 cup milk or yogurt; 1½ ounces natural cheese; 2 ounces processed cheese (e.g., American); 2 cups cottage cheese; 1½ cups ice cream (choose fat-free or low-fat most often)

Meat, poultry, fish, dry beans, eggs, and nuts (meat and beans† groups)

5½- to 6½-ounce equivalents

Most meat and poultry choices should be lean or low fat. Fish, nuts, and seeds contain healthy oils, so choose these foods frequently instead of meat or poultry.

1 ounce-equivalent = 1 ounce (30 g) meat, poultry, or fish; ¼ cup cooked dried beans†; 1 egg; 1 tablespoon (15 mL) peanut butter; ½ ounce nuts or seeds

Oils

6 teaspoons (30 mL)

Choose oils rather than solid fats. Solid fats are fats that are solid at room temperature, such as butter, shortening, stick margarine, and pork, chicken, or beef fat. Read the label: choose products with no trans fats, limit intake of saturated fats, and choose oils high in monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats.

1 teaspoon = 1 teaspoon liquid oil (e.g., olive, canola, sunflower, safflower, peanut, soybean, cottonseed) or soft margarine (tub or squeeze bottle); 1 tablespoon mayonnaise or Italian salad dressing; ¾ tablespoon Thousand Island salad dressing; 8 large olives; ⅙ medium avocado; ⅓ ounce dry roasted peanuts, mixed nuts, cashews, sunflower seeds†

Fluids

BEVERAGE OR FOOD

CAFFEINE (MG)

Coffee (8 oz [240 mL])

95

Espresso (1 oz [30 mL])

64

Tea, black, brewed (8 oz [240 mL])

47

Tea, ready-to-drink, with lemon (12 oz [360 mL])

7

Tea, green, brewed (8 oz [240 mL])

50

Tea, white, brewed (8 oz [240 mL])

35

Energy drink, Rockstar (8 oz [240 mL])

79

Energy drink, Red Bull (8.4 oz [250 mL])

77

Energy drink, Vault (8 oz [250 mL])

68

Energy drink, AMP (8 oz [240 mL])

74

Cola beverage, regular (12 oz [360 mL])

29

Hot chocolate, homemade or from mix (8 oz [240 mL])

5

Dark chocolate bar (1 oz [30 g])

23

Candy bar, milk chocolate with almonds (1.5 oz [45 g])

7 ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Maternal and Fetal Nutrition

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access