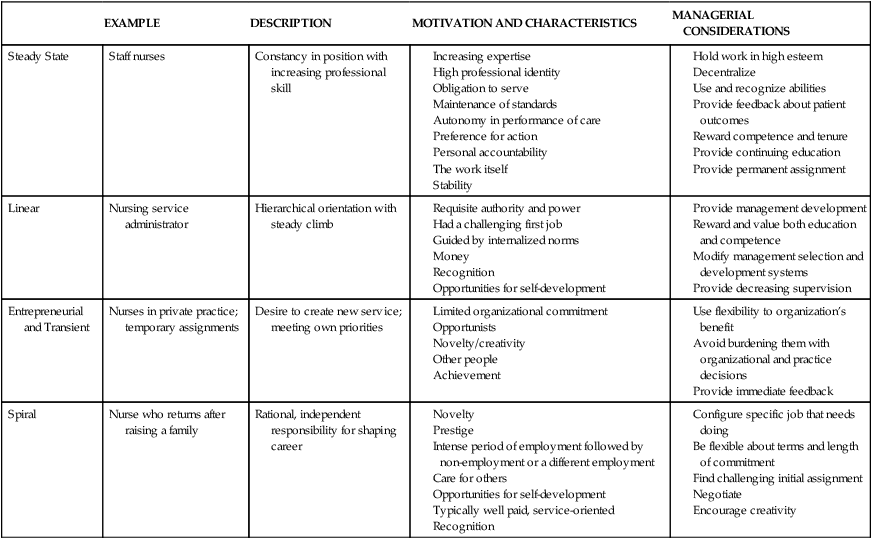

• Differentiate among career styles and how they influence career options. • Analyze person-position fit. • Develop a cover letter and résumé targeted for a specific position. • Analyze critical elements of an interview. • Describe a variety of professional development activities, including academic and continuing education programs. • Identify contributions you could make and benefits you could derive from active involvement in professional organizations. A career can be defined as progress throughout an individual’s professional life. It can be developed in numerous ways, but it begins with selecting positions that contribute to career goals. Because so many roles can be performed in the name of nursing, the driving force for a career option should be the same as the force that drives a decision about a particular position. That force is the fit between a person and the position or career path. There is a relationship between an individual and a position, and that same relational fit is exhibited in a career path (Figure 29-1). A good fit is built on strong, similar goals and tolerable (or growth-producing) differences. The whole of any work situation is composed of the two elements—person and position—interacting in an environment in which other elements influence both. The whole is symbolized by blending a person’s talents with a position’s expectations to create the productive whole. Analyzing positions and the required skills in light of individual talents can help applicants determine positions that fit with their strengths and define gaps to be addressed. When gaps occur, skills development might be needed to form a fit or the position may not be a good fit. Generations may view work, positions, and careers differently, yet many similarities exist across generations. For example, Deal (2007) reported that all generations prefer face-to-face coaching. Younger generations, however, sought more frequent feedback than did older generations. In addition, Deal reported that almost everyone surveyed wanted to learn and thought learning was important. The learning related to the work he or she needed to do, not to the generational group in which he or she was categorized. An important finding was related to the stereotype of younger generations wanting to learn everything via a computer; that was a wrong assumption. The key to applying these points about coaching and learning is that leaders and managers must listen to others to learn what others want and need. This strategy can apply to career development as well. Listening to what individuals tell others about their own interests and strengths can help them identify appropriate resources for personal and professional development and for creating effective networks. Speaking up and listening carefully are important skills that every nurse can use in being successful in a position and in pursuing a career path. Another way to think about career development is to consider the work of Citrin and Smith (2003), who studied “extraordinary” careers. They identified three broad categories of promise, momentum, and harvest. These terms suggest movement from early to late career. Thus, early in one’s career, the focus is on developing skills, establishing credentials, and socializing into the role. Mid-career, the focus often shifts to honing specific areas of expertise (the things by which we will be known) and being more aware of the fit of positions within the broad array of opportunities that will enhance some goal. Finally, in a later career stage, many individuals focus on the profession (the broad view of the work) and how to leave it better off as a result of being a member of the profession. This movement through nursing life is predicated on having a vision of a career as opposed to a series of jobs. Finally, the classic work of Friss (1989) provides another way to look at careers through considering styles (Table 29-1). Her view of four possible career styles describes one being no better than another; rather, each is different. Steady state (positional plateau) careers describe those individuals who select a role and stay in that role throughout the career. This type of career style is common in rural settings and for those individuals who commit their working life to a positional category such as staff nurse, clinic nurse, or nurse practitioner. The focus of this career style is to become increasingly competent in the role and clinical area. Linear careers are those that represent vertical movement in the organizational hierarchy. This movement often creates more organizational knowledge and a more diversified view of what comprises nursing. This movement is characterized by changes in title; for example, moving from staff nurse to nurse manager to director represents this kind of career style. Entrepreneurial and transient style is appealing to nurses who wish to “see the world” or have a creative bent. The final style, spiral, focuses on the movement in and out and up and down. For example, nurses who move from within an organization as a staff nurse to nurse manager at another organization, then move in that organization to a nursing director role, and later leave for another opportunity exemplify this style. TABLE 29-1 Data from Friss, L. (1989). Strategic management of nurses: A policy oriented approach. Owings Mills, MD: AUPHA Press. Being a professional holds both privileges and obligations. The legal privileges and expectations are codified in the state nursing practice acts, rules, and regulations. Because licensure is designed to provide the baseline (i.e., the minimum expectation), it does not identify or obligate any practitioner to function in a professional manner as defined by the profession itself. For example, no practice act identifies membership in a professional association or providing community/professional service as an expectation. Yet the profession, through various professional organizations, embraces the expectation that nurses will belong to professional associations and provide leadership in improving communities. For example, the Forces of Magnetism (www.nursecredentialing.org/Magnet/ProgramOverview/ForcesofMagnetism.aspx) identifies the expectation that nurses are involved in their community. The challenge, of course, is how to incorporate these activities into a busy, committed life! It often is those “additional” activities and interests that enrich a career and provide for invaluable insight into clinical and professional issues. Knowing what is important, what is valued, and the commitment needed forms the basis for understanding one’s self. Whether positions are plentiful or scare, knowing one’s self can focus the available work or selection process toward capitalizing on one’s strengths. Even assessing one’s strengths through a formal avenue (e.g., Strengths Finder 2.0 at www.strengthsfinder.com/113647/Homepage.aspx or Buckingham’s [2008] The Truth about You: Your Secret to Success) can provide insight. Therefore the beginning of creating a person/position fit is understanding the person involved. Throughout school and initial experiences in nursing, insight begins to evolve that helps each of us determine our preferences for our life work. It is not that some positions are valueless; rather, it is that some positions add more to what we want to be able to achieve in the long term than other positions. As an example, any position that offers educational compensation or flexible scheduling might work well for the short term if the goal is to return to school and complete advanced education for a specialized role. Being able to describe yourself from various perspectives is useful. First, knowing your strengths tells you what you bring to a position and what you can rely on. When you know your strengths, you can say what they are in a succinct manner and use them as a filter in reading position descriptions to find your fit and to learn the organizational language. An analysis of your competencies allows you to see what work needs to be done to meet required or desired standards and competencies. Finally, entering into such analyses can help you see the bigger picture of your career and how what you can learn from a particular position might contribute to your overall goals. The career styles described in Table 29-1 include the motivation and characteristics of each style. Seeing how your self-analysis fits with the descriptors in the third column may suggest how you see yourself approaching your career. The goal of all this work is to know yourself well so that your pursuit of a position or career path fits you and your strengths. Position assessment begins with understanding the basics of the organization and its vision and mission. Assessment also requires finding out specifics of the position, which may be available only through an interview. Bolles (2009) points out that most managers look first within the organization to promote someone rather than looking broadly at the talent available. This is in contrast to how many people seek jobs; they look broadly first. So, one key strategy to use is selecting an organization where you want to work, even if the position is not exactly the right one. The potential for inside connections and networking, in addition to knowledge about management styles in the organization and future position openings, can lead you to the position that is the right fit for you. Bolles (2009) also suggests that there are life-changing positions. These can best be described as changing positions and fields simultaneously (such as may occur with a spiral career style). For example, when a charge nurse in a critical care unit assumes the role of a chief nursing officer in a rural community hospital, a major shift has occurred. Nurses who follow a spiral career path, especially if they are second-degree students (meaning they have a degree in another field and then enter nursing), may also experience this phenomenon. These individuals may have worked in another field and now are pursuing their hearts. They may have become bored with a career that had few interactions with people, or they may have studied in fields such as science and realized that the best application of knowledge could occur in patient care. Because of prior career successes, these individuals may craft career patterns that appear very different from the majority of the profession: they are using talents from two fields and are trying to capitalize on both. Table 29-2 defines six key aspects of creating and managing a career. Although each aspect is important, one aspect that can be most useful to consider is the “who”—the mentor you choose. That person can inspire new thinking and new opportunities and steer you to various roles and clinical areas. That person can also create connections for you and help guide decisions related to timing and context. Mentors might even be able to create opportunities for you to test new approaches to clinical care or to new aspects of a position you thought of as boring. TABLE 29-2 KEY ASPECTS OF CREATING AND MANAGING A CAREER Compile as many facts as possible for each of the ten categories identified in Table 29-3. Even if you have no entry for a specific category, retain the heading as a reminder and think about what you would like to be able to list there in the future. If you do not have regular access to a computer, at least keep the information on a CD or flash drive so that you do not need to recreate it the next time. This is your private data bank for information to list on a curriculum vitae or to select for a résumé. TABLE 29-3 A curriculum vitae (or CV) is the documentation of one’s professional life. It is designed to be all-inclusive of facts but not detailed. A curriculum vitae follows some designated flow of information reflective of the ten categories identified in Table 29-3. However, unlike the data collection stage, in which a category is retained even if no data appear, empty categories are not listed on a CV. Typically, a CV begins with your name and contact information. Your name should be most prominent (e.g., larger type size, bolded) and should be followed with contact information listed on separate lines. Your contact information should include address with zip code; phone numbers, designated by work, home, and cell; fax number; e-mail address; and, if you have one, a website address. If you include a website address, use an e-mail account with a professional name; avoid usernames that are overly casual such as “sweetiepie@domain.com” or those that provide personal information such as “crabbynurse@domain.com.” Center the contact information on the CV or place a dividing line under it to help a prospective employer quickly locate that information. Information in the body of the CV should be presented in reverse chronological order. This approach allows a prospective employer to find the most recent (and theoretically most relevant) information quickly. By drawing attention to your most recent accomplishments, the reader gains a sense of where you are in your career. The résumé is a better choice than a CV for advertising your skills and talents to a prospective employer. Because a résumé is brief (typically no more than two pages) and tailored to the position being sought, the information is pointed toward specific position requirements. Details and action words help the reader view you as accomplishing work. Verbs that relate to outcomes (produced, created) are most powerful. Fox (2006) suggested that the purpose of the résumé is to elaborate on what you said during an interview, but often the interviewer will have read your résumé as a basis for scheduling the interview. Either way, it is a good idea to arrive for an interview with a copy of your résumé as a reminder of your capabilities. Bringing a résumé to an interview is especially useful if you were asked previously to provide a CV. This additional work of applying your talents to the specific position in the résumé helps the interviewer see you as fitting in the organization.

Managing Your Career

A Framework

EXAMPLE

DESCRIPTION

MOTIVATION AND CHARACTERISTICS

MANAGERIAL

CONSIDERATIONS

Steady State

Staff nurses

Constancy in position with increasing professional skill

Linear

Nursing service administrator

Hierarchical orientation with steady climb

Entrepreneurial and Transient

Nurses in private practice; temporary assignments

Desire to create new service; meeting own priorities

Spiral

Nurse who returns after raising a family

Rational, independent responsibility for shaping career

Knowing Yourself

Knowing the Position

Career Development

Who

Mentor

What

Role and clinical options

When

“Timing is everything”; always open to opportunities; don’t leave in the middle of a critical project

Where

Local or not; inpatient or outpatient

How

Proactive; your search is your job

Why

Seeking challenge/testing out ideas

Career Marketing Strategies

Data Collection

TOPICS

FACTS NEEDED

1. Education

Name of school, address, phone numbers, website address, years of attendance, date of graduation, name of degree(s) received, minor earned, honors received (e.g., Dean’s List)

2. Continuing education

Dates attended, places, topics and any special outcomes, type and amount of credit earned

3. Experience

Dates of employment, title of position, name of employing agency, location and phone numbers, website address, name of chief executive officer, chief nursing officer, immediate supervisor, salary range, typical duties (role description)

4. Community/institutional service

Dates of service, name of committee/task force and the parent organization (e.g., name of hospital or professional organization), your role on the committee (e.g., chairperson, secretary, member), general description of committee’s functions, any unique accomplishments

5. Publications

Articles: author(s) name(s), year of publication, title, journal, volume, issue, pages; books: author(s), year of publication, title, location and name of publisher

6. Honors

Date, description of award, special factors related to award (e.g., competitive, communitywide, national)

7. Research

Date, title of research, role in research (e.g., principal investigator, co-investigator, team member), funded/unfunded

8. Speeches/presentations given

Date, title of speech presented, place, name of sponsoring organization, nature of the presentation (e.g., keynote, concurrent session), your honorarium

9. Workshops/conferences presented

Date, title of workshop/conference presented, place, name of sponsoring group and nature of the presentation, brief description of the activity, your honorarium

10. Certification

Initial date of certification, expiration date, certifying body, area/type of certification

Curriculum Vitae

Résumé

Managing Your Career

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access