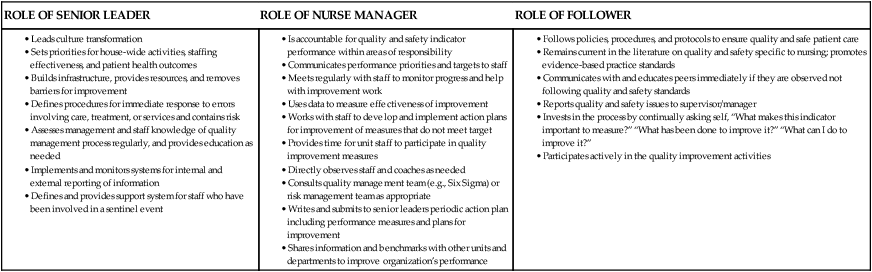

• Apply quality management principles to clinical situations. • Use the six steps of the quality improvement process. • Practice using select quality improvement strategies to do the following: • Identify customer expectations. • Diagram clinical procedures. • Develop standards and outcomes. • Incorporate roles of leaders, managers, and followers to create a quality management culture of continuous readiness. • Apply risk management strategies to an agency’s quality management program. Healthcare agencies and health professionals strive to provide the highest quality, safest, most efficient, and cost-effective care possible. The philosophy of quality management and the process of quality improvement need to shape the entire healthcare culture and provide specific skills for assessment, measurement, and evaluation of patient care. The goal of an organization committed to quality care is a comprehensive, systematic approach that prevents errors or identifies and corrects errors so that adverse events are decreased and safety and quality outcomes are maximized. Leadership must acknowledge safety shortcomings and allocate resources at the patient care and unit levels to identify and reduce risks (Pronovost, Rosenstein, et al., 2008). Quality management and risk management are focused on optimizing patient outcomes and emphasize the prevention of patient care problems and the mitigation of adverse events. Hospital leaders, including nurses, must sharpen their expertise in healthcare quality and patient safety, and staff at all levels must be empowered to act on nursing performance data (Kurtzman & Jennings, 2008). Healthcare systems that demand quality recognize that survival and competitiveness are built on improved patient outcomes. Success depends on a philosophy that permeates the organization and values a continuous process of improvement. It is essential to integrate patient safety and risk management into broader quality initiatives. Nurses must be prepared to continuously improve the quality and safety of healthcare systems within which they work and must focus on the six competencies identified by Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN): patient-centered care, teamwork and collaboration, evidence-based practice, quality improvement, safety, and informatics (Cronenwett et al., 2007). Quality necessitates maintaining safety in patient care, with a continual focus on clinical excellence from the entire multidisciplinary team. Patient safety is a key component of quality improvement and clinical governance. Moreover, the prevention of adverse events is paramount to improved patient outcomes. In this chapter, quality management refers to a philosophy that defines a healthcare culture emphasizing customer satisfaction, innovation, and employee involvement. Similarly, quality improvement refers to an ongoing process of innovation, prevention of error, and staff development that is used by institutions that adopt the quality management philosophy. Nurses maintain a unique role in quality management and quality improvement because of the amount of direct patient care provided at the bedside and because they have an understanding of the day-to-day issues and “real world” nursing involved in delivery of care. Involvement of nurses in patient care improvement efforts (e.g., patient flow problems, safe delivery of care during low staffing or high census and high acuity times, communication problems associated with complex patients, improving medication safety) can not only promote quality and safety of patient care but also positively affect job satisfaction and improve the work environment (Hall, Moore, & Barnsteiner, 2008). Non-healthcare industries have excelled in focusing on process improvement as part of their core operating strategies. Numerous business management philosophies have been expanded and modified for use in healthcare organizations. For example, Six Sigma, a data-driven approach targeting a nearly error-free environment, empowers employees to improve processes and outcomes. As healthcare organizations “go lean,” nurses are challenged to eliminate unnecessary steps and reduce wasted processes (saving time and money) to improve quality and the patient experience (de Koning, Verver, van den Heuvel, Bisgaard, & Does, 2006). To achieve this, Six Sigma uses a five-step methodology known as DMAIC, which stands for define opportunities, measure performance, analyze opportunity, improve performance, and control performance to improve existing processes. Within healthcare systems, QI combines the assessment of structure (e.g., adequacy of staffing, effectiveness of computerized charting, availability of unit-based medication delivery systems), process (e.g., timeliness and thoroughness of documentation, adherence to critical pathways or care maps), and outcome (e.g., patient falls, hospital-acquired infection rates, patient satisfaction) standards. These three factors are usually considered interrelated, and research has been conducted to determine the characteristics of effective structures and processes that would result in better outcomes. The Literature Perspective on p. 392 expands the classic Donabedian model of the structure, process, and outcome framework in promoting quality in healthcare organizations. Recognizing the relationship between quality patient care and nursing excellence, the American Academy of Nursing undertook a study that resulted in the distinction known as Magnet™. The American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC) created a process called the Magnet Recognition Program®. The term Magnet™ hospital was chosen to describe a hospital that attracts and retains nurses even in times of nursing shortages. Magnet™ hospital research has examined the characteristics of hospital systems that impede or facilitate professional practice in nursing and also promote quality patient outcomes. Common organizational characteristics of Magnet™ hospitals include structure factors (e.g., decentralized organizational structure, participative management style, and influential nurse executives) and process factors (e.g., professional autonomy and decision making, ongoing professional development/education). Organizations that have not pursued Magnet™ status can implement strategies (e.g., introducing a clinical ladder program, facilitating professional certification, assisting with evidence-based projects, enhancing the new graduate nurse orientation program) to promote a professional practice environment for staff nurses and improve organizational outcomes (Lacey et al., 2008). The combination of QI ideas from theory and research is sometimes referred to as total quality management (TQM) or, more simply, quality management (QM). The basic principles of QM are summarized in Box 20-1 and are developed further in the next section of this chapter. Leaders, managers, and followers must be committed to QI. Top-level leaders and managers retain the ultimate responsibility for QM but must involve the entire organization in the QI process. Although some healthcare organizations have achieved significant QI results without systemwide support, total organizational involvement is necessary for a culture transformation. If all members of the healthcare team are to be actively involved in QI, clear delineation of roles within a nonthreatening environment must be established (Table 20-1). TABLE 20-1 ROLES/RESPONSIBILITIES IN QUALITY IMPROVEMENT PLAN To work effectively in a democratic, quality-focused corporate environment, nurses and other healthcare workers must accept QI as an integral part of their role. Nurses have a direct impact on patient safety and healthcare outcomes (Kurtzman & Jennings, 2008). Nursing must be recognized and empowered to mobilize performance improvement knowledge and practice measures throughout the organization. When a separate department controls quality activities, healthcare managers and workers often relinquish responsibility and commitment for quality control to these quality specialists. Employees working in an organizational culture that values quality freely make suggestions for improvement and innovation in patient care. Exercise 20-1 may help nurses make QI suggestions. Communication should flow freely within the organization. When healthcare professionals understand each other’s roles and can effectively communicate and work together, patients are more likely to receive safe, quality care (Hall et al., 2008). Because QM stresses improving the system, detection of employees’ errors is not stressed; and if errors occur, re-education of staff is emphasized rather than imposition of punitive measures. When patient safety indicators are used to examine hospital performance, the focus of error analysis shifts from the individual provider to the level of the healthcare system (Glance, Li, Osler, Mukamel, & Dick, 2008). Every nurse and healthcare agency has internal and external customers. Internal customers are people or units within an organization who receive products or services. A nurse working on a hospital unit could describe patients, nurses on the other shifts, and other hospital departments as internal customers. External customers are people or groups outside the organization who receive products or services. For nurses, these external customers may include patients’ families, physicians, managed care organizations, and the community at large. Some customers (e.g., physicians, patient families) could be either internal or external customers depending on the actual care environment. Managers and staff nurses can use Exercise 20-2 to identify their internal and external customers. Public reporting of quality and risk data is changing the way customers make decisions about health care and is intended to improve care through easily accessed information. For example, Hospital Compare (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2009) allows customers to (1) find information on how well hospitals care for patients with certain medical conditions or surgical procedures and (2) access patient survey results about the quality of care received during a recent hospital stay. This information allows customers to compare the quality of care hospitals provide. Hospital Compare was created through the efforts of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS), and other members of the Hospital Quality Alliance (HQA). The information on this website comes from hospitals that have agreed to submit quality information for Hospital Compare to make public. QI focuses on outcomes. Patient outcomes are statements that describe the results of health care. They are specific and measurable and describe patients’ behavior. Outcome statements may be based on patients’ needs, ethical and legal standards of practice, or other standardized data systems. Healthcare organizations that implement nursing-sensitive performance measures value nurses and have a strong commitment to patients and a goal to outperform competitors (Kurtzman & Jennings, 2008). The QI process is a structured series of steps designed to plan, implement, and evaluate changes in healthcare activities. Many models of the QI process exist, but most parallel the nursing process and all contain steps similar to those listed in Box 20-2. The six steps can easily be applied to clinical situations. In the following example, staff at a community clinic use the QI process to handle patient complaints about excessive wait times. The QI process begins with the selection of a clinical activity for review. Theoretically, any and all aspects of clinical care could be improved through the QI process. However, QI efforts should be concentrated on changes to patient care that will have the greatest effect. To determine which clinical activities are most important, nurse managers or staff nurses may interview or survey patients about their healthcare experiences or may review unmet quality standards. The results of the research study in the Research Perspective on p. 396 identify prevention of errors during hand-off.

Managing Quality and Risk

Introduction

Quality Management in Health Care

Evolution of Quality Management

Quality Management Principles

Involvement

Goal

Customers

Focus

The Quality Improvement Process

Identify Consumers’ Needs

Managing Quality and Risk

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access