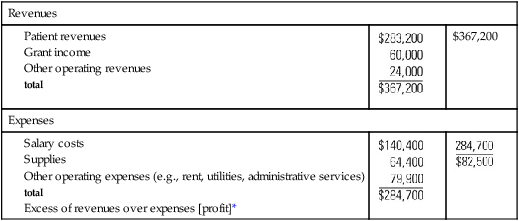

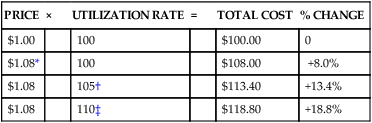

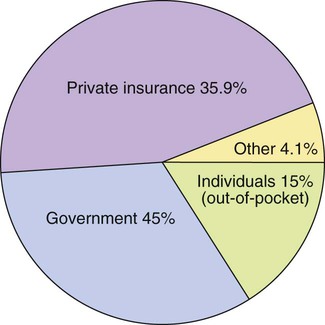

• Explain several major factors that are escalating the costs of health care. • Evaluate different reimbursement methods and their incentives to control costs. • Differentiate costs, charges, and revenue in relation to a specified unit of service, such as a visit, hospital stay, or procedure. • Value why all healthcare organizations must make a profit. • Give examples of cost considerations for nurses working in managed care environments. • Discuss the purpose of and relationships among the operating, cash, and capital budgets. • Explain the budgeting process. Healthcare costs in the United States continue to rise at a rate greater than general inflation. In 2009, for example, Americans spent $2.2 trillion for health care—approximately 16.2% of the gross domestic product (GDP). This equals $7026 per person. The health share of the GDP is projected to increase to 19.5% in 2017 (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], 2008). Yet millions of uninsured and underinsured Americans do not have access to basic healthcare services. With the exception of South Africa, the United States was the only industrialized nation where health care is viewed as a privilege rather than a right. The large portion of the GDP that is spent on health care poses problems to the economy in other ways, too. Funds are diverted from needed social programs such as childcare, housing, education, transportation, and the environment. The price of goods and services is increased, and therefore the country’s ability to compete in the international marketplace is compromised. The cost of providing health care to automobile manufacturing employees added from $1100 to $1500 to the cost of each of the 4.65 million vehicles General Motors sold in 2004 (Appleby & Carty, 2005). As the amount of the GDP devoted to healthcare expenses rises, the more vulnerable the healthcare industry is to external influences. This creates a major concern for an industry that already expresses concerns about being overregulated. Total healthcare costs are a function of the prices and the utilization rates of healthcare services (Costs = Price × Utilization) (Table 12-1). Price is the rate that healthcare providers set for the services they deliver, such as the hospital rate or physician fee. Utilization refers to the quantity or volume of services provided, such as diagnostic tests provided or number of patient visits. TABLE 12-1 RELATIONSHIP OF PRICE AND UTILIZATION RATES TO TOTAL HEALTHCARE COSTS Price inflation and administrative inefficiency are leading contributors to increasing prices for health services. In recent decades, rises in healthcare prices have dramatically outpaced general inflation. Examples of factors that stimulate price inflation are physician incomes that rise faster than average worker earnings and the high prices of prescription drugs, which are often 50% higher than prices in other nations (Bodenheimer & Grumbach, 2009). Administrative inefficiency or waste is primarily a result of the large numbers of clerical personnel whom organizations use to process reimbursement forms from multiple payers. U.S. hospitals spend an average of 20% of their budgets on billing administration alone! This single fact indicates why some hospital administrators advocate for the elimination of multiple payers. The way health care is financed contributes to rising costs. When health care is reimbursed by third-party payers, consumers are somewhat insulated from personally experiencing the direct effects of high healthcare costs. For example, the huge rise in consumer demand for prescription drugs since 1995 was fueled by low copayments for drugs required by most insurance companies (Heffler et al., 2004). As consumer out-of-pocket expenses for drugs increase, consumer demand should decrease. In most instances, however, consumers do not have many incentives to consider costs when choosing among providers or using services. In addition, the various methods of reimbursement have implications for how providers price and use services. Health care is paid for by four sources: government (45%); private insurance companies (35.9%); individuals (15%); and other, primarily philanthropy (4.1%) (Figure 12-1). Three fourths of the government funding is at the federal level. Federal programs include Medicare and health services for members of the military, veterans, American Indians, and federal prisoners. Medicare, the largest federal program, was established in 1965 and pays for care provided to people 65 years of age and older and some disabled individuals. Medicare Part A is an insurance plan for hospital, hospice, home health, and skilled nursing care that is paid for through Social Security taxes. Nursing home care that is mainly custodial is not covered. Medicare Part B is an optional insurance that covers physician services, medical equipment, and diagnostic tests. Part B is funded through federal taxes and monthly premiums paid by the recipients. Medicare does not cover outpatient medications, eye or hearing examinations, or dental services. The drug benefit plan, effective in 2006, has been viewed as beneficial but very difficult to understand. Four major payment methods are used for reimbursing healthcare providers: charges, cost-based reimbursement, flat-rate reimbursement, and capitated payments (Zelman, McCue, Millikan, & Glick, 2003). These methods are summarized in Box 12-1. Health-service researchers do not agree on the exact effects of these reimbursement methods on cost and quality. However, considering these effects is important because changes in payment systems have implications for how care is provided in healthcare organizations. Health care is a major public concern, and rapid changes are occurring in an attempt to reduce costs and improve the health and wellness of the nation. As shown in Box 12-2, strategies shaping the evolving healthcare delivery system include managed care; organized delivery systems (ODSs); and competition based on price, patient outcomes, and service quality. These strategies affect both the pricing and use of health services. Managed care is a health plan that brings together the delivery and financing function into one entity, in contrast with a traditional fee-for-service plan, in which insurers pay providers based on costs (Finkler & McHugh, 2007). A major goal of managed care is to decrease unnecessary services, thereby decreasing costs. Managed care also works to ensure timely and appropriate care. HMOs are a type of managed care system in which the primary physician serves as a gatekeeper who determines what services the patient uses. Because HMOs are paid on a capitated basis, it is to the HMO’s advantage to practice prevention and use ambulatory care rather than more expensive hospital care. In other forms of managed care, a non-physician case manager arranges and authorizes the services provided. Many insurance companies have used case managers for years. Nurses who work in home health and ambulatory settings often communicate with insurance company case managers to plan the care for specific patients. PPOs and point-of-service (POS) plans are other types of managed care plans that give the patient more options than traditional HMOs do for selecting providers and services. All private healthcare organizations must make a profit to survive. If expenses are greater than revenues, the organization experiences a loss. If revenues equal expenses, the organization breaks even. In both cases, nothing is left over to replace facilities and equipment, expand services, or pay for inflation costs. Some healthcare organizations can survive in the short run without making a profit because they use interest from investments to supplement revenues. The long-term viability of any private healthcare organization, however, depends on consistently making a profit. Box 12-3 presents a simplified example of an income statement from a neighborhood not-for-profit nursing center.

Managing Costs and Budgets

Introduction

What Escalates Healthcare Costs?

PRICE

×

UTILIZATION RATE

=

TOTAL COST

% CHANGE

$1.00

100

$100.00

0

$1.08*

100

$108.00

+8.0%

$1.08

105†

$113.40

+13.4%

$1.08

110‡

$118.80

+18.8%

How Is Health Care Financed?

Reimbursement Methods

The Changing Healthcare Economic Environment

Why Is Profit Necessary?

Managing Costs and Budgets

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access