Disorders of the lower respiratory tract such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and respiratory failure

Findings on assessment

Diagnostic tests for specific respiratory disorders

Collaborative treatment strategies for particular disorders to maximize ventilation and oxygenation

CASE STUDY

CASE STUDY

♦ What physiologic changes cause wheezing?

♦ Why is her PEFR decreased during an asthma attack?

♦ What could have caused this asthma attack?

RESPIRATORY TRACT DEFENSES

RESPIRATORY TRACT DEFENSESinspired air and protection of the respiratory tract, as well as humidification and temperature regulation. The first line of defense is air filtration in the nose. The nasal hairs and mucus trap many foreign particles. Obviously, mouth breathing circumvents this system and reduces its effectiveness. The sneezing reflex is initiated in the nose when irritation or particles stimulate the trigeminal nerve. The cough reflex also assists in expelling particles or mucus that is occluding or irritating the airways.

Cilia are small hairs that line the respiratory tract and constantly beat to move particles and mucus up the respiratory passages to where they can be expelled by coughing, sneezing, or swallowing.

Cilia are small hairs that line the respiratory tract and constantly beat to move particles and mucus up the respiratory passages to where they can be expelled by coughing, sneezing, or swallowing. The nurse’s role in treating patients with respiratory disorders is to maintain the patient’s oxygenation by optimizing ventilation, diffusion, and perfusion.

The nurse’s role in treating patients with respiratory disorders is to maintain the patient’s oxygenation by optimizing ventilation, diffusion, and perfusion.or malignancy. The nurse’s role in treating patients with respiratory disorders is to maintain the patient’s oxygenation by optimizing ventilation, diffusion, and perfusion. Nursing care of patients with respiratory disorders requires the following:

♦ Understanding normal respiratory anatomy and physiology

♦ Distinguishing between different disorders of the upper and lower airways

♦ Assessment of the patient based on the knowledge of different signs and symptoms of respiratory disorders and their impact on the patient’s functioning

♦ Developing nursing and collaborative care plans with appropriate long- and short-term goals with the patient

♦ Implementing the principles of oxygenation into the care plans

♦ Evaluating the effectiveness of the interventions

♦ Revising the treatment plan as necessary

DISORDERS OF THE UPPER AIRWAYS

DISORDERS OF THE UPPER AIRWAYSNovember and March, with most adults having two to three colds per year. The usual incubation period for acute rhinitis is 1 to 4 days after exposure to droplets containing the virus.

The most frequent infection in human beings is acute rhinitis.

The most frequent infection in human beings is acute rhinitis. The usual incubation period for acute rhinitis is 1 to 4 days after exposure to droplets containing the virus.

The usual incubation period for acute rhinitis is 1 to 4 days after exposure to droplets containing the virus.Table 3-1 Symptoms of the Common Cold | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The patient’s temperature and white blood cell count usually remain normal with a cold but may be elevated with a bacterial infection.

The patient’s temperature and white blood cell count usually remain normal with a cold but may be elevated with a bacterial infection. Elderly patients and those with chronic respiratory disease are particularly prone to complications from the common cold, including sinusitis, bronchitis, and pneumonia.

Elderly patients and those with chronic respiratory disease are particularly prone to complications from the common cold, including sinusitis, bronchitis, and pneumonia.include sinusitis, drugs such as birth control pills and antihypertensives, as well as smoke and seasonal allergies.

Table 3-2 How to Obtain a Throat Culture | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

♦ Ensure adequate fluid intake (at least 2500 mL/day or one half the body weight in pounds equals the total ounces per day).

♦ Avoid dairy products that may thicken secretions.

♦ Humidify the air with a vaporizer, and use saline nasal drops to maintain moist nasal mucus membranes.

♦ Allow adequate rest.

♦ Use over-the-counter medications such as antihistamines (chlorpheniramine or pseudoephedrine) to decrease nasal discharge.

Acute rhinitis is a self-limiting condition that usually resolves in 7 to 10 days.

Acute rhinitis is a self-limiting condition that usually resolves in 7 to 10 days.Table 3-3 Cold Prevention | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Rhinitis medicamentosa is rebound nasal congestion after prolonged antihistamine use.

Rhinitis medicamentosa is rebound nasal congestion after prolonged antihistamine use.

♦ Symptoms last more than 7 days.

♦ Temperature exceeds 100.5°F.

♦ Nasal discharge becomes yellow to green or is accompanied by face pain or headache.

♦ The patient has frequently recurring colds.

In allergic rhinitis, inhaled substances (pollen, animal dander, or dust) cause a type I hypersensitivity reaction and the release of potent vasoactive and inflammatory substances by the mast cells in the nasal mucosa.

In allergic rhinitis, inhaled substances (pollen, animal dander, or dust) cause a type I hypersensitivity reaction and the release of potent vasoactive and inflammatory substances by the mast cells in the nasal mucosa. When assessing a patient with allergic rhinitis, ask the patient about occupation, smoke exposure, life stresses, alcoholic beverage intake, and drug exposure.

When assessing a patient with allergic rhinitis, ask the patient about occupation, smoke exposure, life stresses, alcoholic beverage intake, and drug exposure.control would indicate an allergic response. Identification of the allergen provides a direction for treatment.

Careful questioning of patients with allergic rhinitis may identify specific substances such as foods, food dyes, molds in cheese, wine, dried fruit, and some drugs that stimulate allergic responses.

Careful questioning of patients with allergic rhinitis may identify specific substances such as foods, food dyes, molds in cheese, wine, dried fruit, and some drugs that stimulate allergic responses.Table 3-4 Reducing Exposure to Pollen | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Table 3-5 Reducing Exposure to Allergens | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Antihistamines are the most frequently used treatment for allergic rhinitis.

Antihistamines are the most frequently used treatment for allergic rhinitis.patients about the treatment plan and possible side effects, and accommodating the patient’s schedule.

The desensitization process (immunotherapy) involves the subcutaneous injection of a known allergen in gradually increasing doses to increase the patient’s tolerance to the substance.

The desensitization process (immunotherapy) involves the subcutaneous injection of a known allergen in gradually increasing doses to increase the patient’s tolerance to the substance. The most common presenting symptom of sinusitis is facial pain and headache.

The most common presenting symptom of sinusitis is facial pain and headache.10 to 14 days, and topical vasoconstrictors such as phenylephrine for, at most, 7 days. It is important to teach the patient about finishing the entire course of antibiotics even if he or she is feeling better. This will prevent reinfection with resistant organisms.

Nosebleed, or epistaxis, occurs commonly and may result from trauma (including nasal fracture and nose picking), infections such as sinusitis and rhinitis, drying of the mucous membranes, bleeding disorders, malignancies of the nose or paranasal sinuses, hypertension, and some systemic infections such as scarlet fever.

Nosebleed, or epistaxis, occurs commonly and may result from trauma (including nasal fracture and nose picking), infections such as sinusitis and rhinitis, drying of the mucous membranes, bleeding disorders, malignancies of the nose or paranasal sinuses, hypertension, and some systemic infections such as scarlet fever.to be packed to apply direct pressure to the bleeding site. Chronic or recurrent nosebleeds may indicate a bleeding tendency and a need for further evaluation.

The most common benign growth in the nasal passage is a papilloma.

The most common benign growth in the nasal passage is a papilloma. Pharyngitis, or a sore throat, may cause pain, especially when swallowing, and tender lymph glands in the neck.

Pharyngitis, or a sore throat, may cause pain, especially when swallowing, and tender lymph glands in the neck.

♦ Chronic use of cigarettes

♦ Age over 40 years old

♦ Use of chewing tobacco

♦ Regular use of alcohol

because it can destroy the blood vessels in the jawbone. Salivary glands may also be destroyed by radiation therapy, predisposing the patient to a dry mouth (xerostomia), altered taste perceptions, accelerated tooth decay, difficulty chewing, swallowing, and speaking.

Salivary glands may also be destroyed by radiation therapy, predisposing the patient to a dry mouth (xerostomia), altered taste perceptions, accelerated tooth decay, difficulty chewing, swallowing, and speaking.

Salivary glands may also be destroyed by radiation therapy, predisposing the patient to a dry mouth (xerostomia), altered taste perceptions, accelerated tooth decay, difficulty chewing, swallowing, and speaking.

♦ Maintaining a patent airway

♦ Ensuring adequate nutrition

♦ Teaching patient about mouth care

♦ Controlling treatment side effects

♦ Providing alternative methods of communication

♦ Recognizing changes in body image and self-esteem that may occur after treatment

Hoarseness and unnatural diminution of the voice may also occur due to chronic overuse of the voice, exposure to inhaled irritants such as cigarette smoke or volatile gases, allergic reactions, or endotracheal intubation.

Hoarseness and unnatural diminution of the voice may also occur due to chronic overuse of the voice, exposure to inhaled irritants such as cigarette smoke or volatile gases, allergic reactions, or endotracheal intubation.Table 3-6 Care of the Mouth During Cancer Treatment | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Voice rest involves not only refraining from talking but also from whispering and heavy lifting, which strain the larynx.

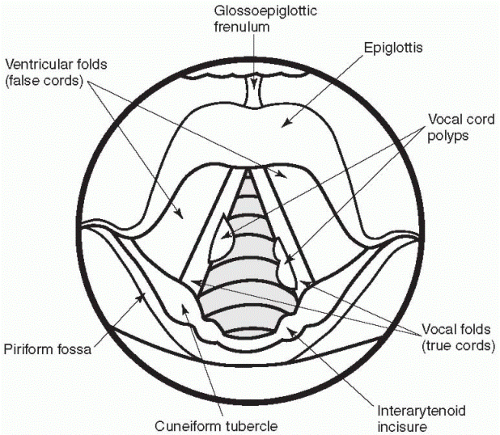

Voice rest involves not only refraining from talking but also from whispering and heavy lifting, which strain the larynx. Vocal cord polyps develop as a result of chronic voice abuse or inhalation of irritants such as cigarette smoke.

Vocal cord polyps develop as a result of chronic voice abuse or inhalation of irritants such as cigarette smoke.with a diminished or hoarse voice and possibly difficulty breathing and swallowing. Identification of the cause is vitally important to protect the airway.

Respiratory distress resulting from laryngeal trauma may require emergency intubation.

Respiratory distress resulting from laryngeal trauma may require emergency intubation.and packing may be inserted to stabilize the area. If there was not any displacement of the nasal bones, placement of a cast over the dorsum of the nose may protect it from further trauma.

wiring together of the upper and lower jawbones by a series of stainless steel wires and elastics.

Table 3-7 Warning Signs of Head and Neck Cancer | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

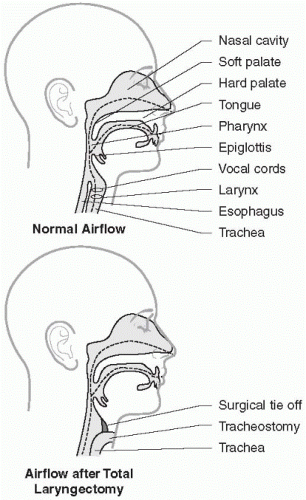

is made from the trachea to the anterior neck to maintain the airway. The pharynx is sutured to the esophagus to permit swallowing.

Figure 3-2 Altered airflow after total laryngectomy. |

DISORDERS OF THE LOWER RESPIRATORY TRACT

DISORDERS OF THE LOWER RESPIRATORY TRACTtherapist all contributing to the development of the best care plan for the patient. In this section, acute infections (influenza, acute bronchitis, pneumonia, and tuberculosis) will be reviewed first followed by diseases of chronic airflow limitation (asthma, chronic bronchitis, and emphysema), acute respiratory failure, adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), pulmonary vascular disorders (pulmonary embolus and pulmonary hypertension), pleural effusion, lung cancer, and chest trauma including pneumothorax. (Specific interventions to maintain oxygenation such as oxygen therapy, tracheostomy, mechanical ventilation, thoracentesis, and chest tube maintenance and endotracheal suctioning are reviewed in Chapter 5.)

Influenza may be a serious infection, particularly in those over 65 years of age, immunocompromised patients, and those with chronic lung and heart disease.

Influenza may be a serious infection, particularly in those over 65 years of age, immunocompromised patients, and those with chronic lung and heart disease.resolve spontaneously in 7 days. Secondary complications may develop after the acute infection and may be related to bacterial infections that may include sinusitis, otitis media (infection of the middle ear), bacterial pneumonia, and bronchitis. These secondary bacterial infections occur just as the patient is starting to feel better or when symptoms are prolonged after the normal influenza course.

Prolonged courses of influenza (greater than 2 weeks of symptoms) indicate the need for additional assessment, especially in the elderly or otherwise compromised patients.

Prolonged courses of influenza (greater than 2 weeks of symptoms) indicate the need for additional assessment, especially in the elderly or otherwise compromised patients. Acetaminophen is preferred over aspirin as an analgesic and antipyretic because of the risk of Reye’s syndrome, a rare complication of influenza that causes liver failure and encephalitis.

Acetaminophen is preferred over aspirin as an analgesic and antipyretic because of the risk of Reye’s syndrome, a rare complication of influenza that causes liver failure and encephalitis.influenza vaccine should not be given to individuals with an allergy to egg whites. Side effects to the vaccine are infrequent and include redness and tenderness at the vaccination site and, rarely, malaise and fever.

The influenza vaccine should not be given to individuals with an allergy to egg whites.

The influenza vaccine should not be given to individuals with an allergy to egg whites. The most common infective agents in acute bronchitis are Staphylococcus aureus, Pneumococcus, and Haemophilus influenza.

The most common infective agents in acute bronchitis are Staphylococcus aureus, Pneumococcus, and Haemophilus influenza. Symptoms of acute bronchitis include a productive cough, fever, malaise, substernal pain especially when coughing, and auscultatory crackles and wheezes.

Symptoms of acute bronchitis include a productive cough, fever, malaise, substernal pain especially when coughing, and auscultatory crackles and wheezes.excessive secretions need to be cleared from the lungs. Expectorants (such as guaifenesin) may be useful in relieving chest congestion. Cigarette smokers are encouraged to stop smoking, as this further irritates the lining of the bronchi.

Older adults with pneumonia may present with confusion and lethargy rather than fever and cough.

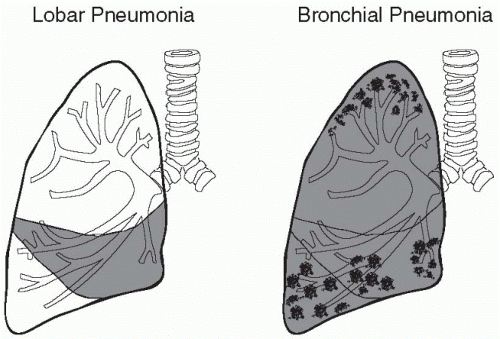

Older adults with pneumonia may present with confusion and lethargy rather than fever and cough.patterns: either lobar or bronchial pneumonia (see Figure 3-3). Lobar pneumonia is so named because a chest X-ray reveals inflammation of a lobe of the lung. Approximately 90% of all forms of lobar pneumonia are caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae. The symptoms of lobar pneumonia are rapid onset of malaise, chills, high fever, and leukocytosis (e.g., increased white blood cell count). Initially, the cough may produce watery sputum, and the breath sounds may be diminished due to congestion in the alveolar walls. Later, the sputum becomes rusty colored or purulent. Pleuritic pain, especially on deep respiratory movements, may be present.

Figure 3-3 Lobar and bronchial pneumonia. |

Bronchial pneumonia tends to be a disease of the very young, the very old, and the immunocompromised.

Bronchial pneumonia tends to be a disease of the very young, the very old, and the immunocompromised. Many different organisms can cause bronchial pneumonia, including the previously mentioned Streptococcus pneumoniae, as well as Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Many different organisms can cause bronchial pneumonia, including the previously mentioned Streptococcus pneumoniae, as well as Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.as well as Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nosocomial pneumonia is pneumonia that develops within 48 hours of admission to a healthcare facility.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree