General health assessment

Physical assessment of the cardiovascular system

Heart sounds

Diagnostic testing

CASE STUDY

CASE STUDY

♦ How would you explain the purpose of the cardiac catheterization to Mr. H?

♦ What allergies would you ask Mr. H about prior to the procedure?

♦ What feelings should Mr. H report to the nurses during the procedure?

♦ Why is bed rest important after the catheterization?

tissue demands and can alter flow to meet the demands of the body. This chapter will review the assessment of the cardiovascular system as it pertains to tissue perfusion and cell oxygenation.

Perfusion through the cardiovascular network is a closed system that responds to changes in pressure.

Perfusion through the cardiovascular network is a closed system that responds to changes in pressure. GENERAL ASSESSMENT

GENERAL ASSESSMENT ASSESSMENT OF THE CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM

ASSESSMENT OF THE CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM

♦ Heart disease—Acute, chronic, or congenital heart problems, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, heart murmurs, rheumatic fever, or varicose veins

♦ Lifestyle—Occupation, hobbies, sleep habits, stressors, exercise, smoking, and alcohol intake

♦ Medications—Cardiac medications, antihypertensives, over-thecounter medications, oral contraceptives, herbal remedies, and nutritional supplements

♦ Nutritional habits—Caloric intake, fat, salt, and caffeine consumption

♦ Chest pain—Including arm, shoulder, and neck pain, and epigastric discomfort, as well as timing of the pain to activities

♦ Pain in the extremities on exertion—Intermittent claudication is relieved by rest, and heaviness in the extremities caused by varicose veins is relieved by rest and elevation.

♦ Dyspnea on exertion or with ordinary activities—Note the timing, the precipitating activity, and the alleviating factors.

♦ Orthopnea or difficulty breathing when recumbent—Note the timing of the orthopnea, including paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (PND). Ask about the number of pillows the patient uses when sleeping.

♦ Palpitations (awareness of heart beating)—Note any precipitating factors like caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, sugar, or stress. Also ask about awareness of skipped beats.

♦ Edema of the extremities—Note location of unilateral or bilateral swelling, any discoloration of the extremities, presence of ulcerations, and time during the day when the edema is noticeable.

♦ Episodes of dizziness or fainting—These may indicate cardiac arrhythmias, postural hypotension, or a vasovagal response.

and quiet. Start by assessing the skin and mucus membranes: color, lesions, ulcers, pigmentation changes, temperature, and hair distribution on the extremities. Patients with venous insufficiency may have brownish pigmentation or ulcers on the lower extremities. Those with arterial insufficiency may present with reddened, cool, or swollen extremities that are hairless. Check the nail beds for clubbing, a symptom of central cyanosis.

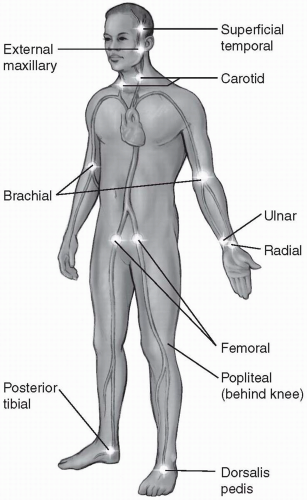

than 1 second after tissue compression), and the affected extremity starts to blanch when elevated above the heart for 1 to 2 minutes. When patients have venous insufficiency of the extremities, the pulses are present but may be difficult to palpate due to peripheral edema.

When a pulse is irregular, note the type of irregularity: regularly irregular (e.g., beat, beat, pause, beat, beat, pause), irregular with respiration (e.g., an increasing rate with inspiration and decreasing rate with expiration), or totally irregular.

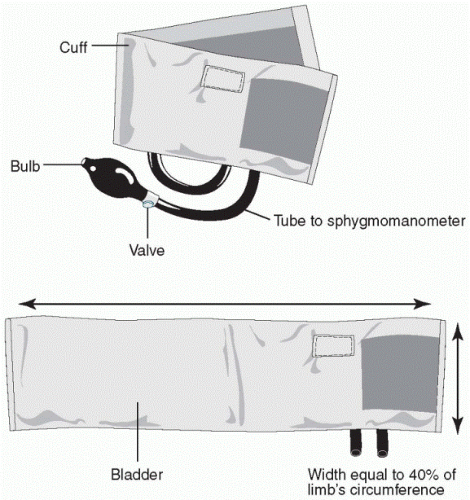

When a pulse is irregular, note the type of irregularity: regularly irregular (e.g., beat, beat, pause, beat, beat, pause), irregular with respiration (e.g., an increasing rate with inspiration and decreasing rate with expiration), or totally irregular. When hypertension is suspected, the blood pressure should be repeated on three separate occasions.

When hypertension is suspected, the blood pressure should be repeated on three separate occasions. Dehydration, hypovolemia, and certain antihypertensive medications are common causes of postural hypotension.

Dehydration, hypovolemia, and certain antihypertensive medications are common causes of postural hypotension.Table 6-1 Measuring Blood Pressure | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Causes of pulsus paradoxus include pericardial tamponade, pulmonary hypertension, and restrictive pericarditis.

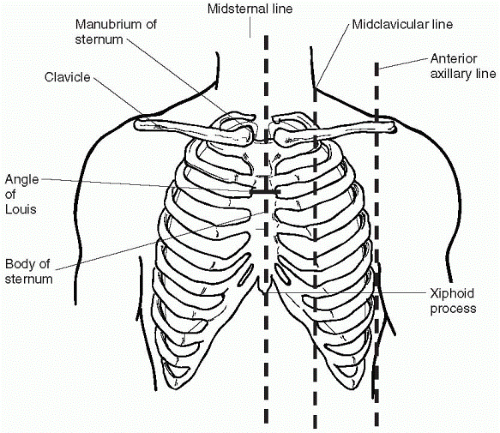

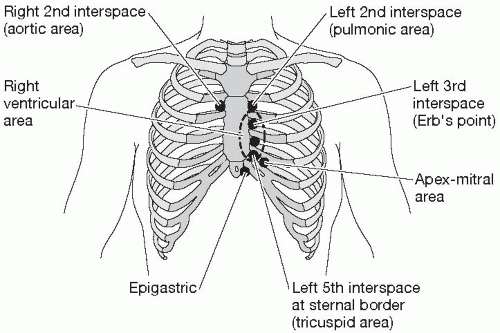

Causes of pulsus paradoxus include pericardial tamponade, pulmonary hypertension, and restrictive pericarditis. The landmarks for both cardiac and respiratory assessments are established by the anatomy of the thorax: the midsternal line, the midclavicular line, the sternal notch, the midscapular line, the midaxillary line, and the intercostal spaces between the ribs. The examination of the chest follows three steps: inspection, palpation, and auscultation.

The landmarks for both cardiac and respiratory assessments are established by the anatomy of the thorax: the midsternal line, the midclavicular line, the sternal notch, the midscapular line, the midaxillary line, and the intercostal spaces between the ribs. The examination of the chest follows three steps: inspection, palpation, and auscultation.

|

Take care to drape female patients as much as possible while allowing for adequate visualization of the thorax during assessment.

Take care to drape female patients as much as possible while allowing for adequate visualization of the thorax during assessment.

Position the patient in a supine position with the head of the bed at a 30° angle and turn the patient’s head slightly away from the side being inspected.

Use oblique lighting and observe the neck for the pulsation of the jugular vein on either side of the neck. It is usually above the sternal notch or just posterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Find the highest point up the neck where the jugular venous pulsation is visible.

Measure from the sternal angle (the connection of the second ribs to the sternum and manubrium) to this level using a vertical ruler and a horizontal reference point to the highest point of jugular venous pulsation (see Figure 6-5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree