Assessment of the Respiratory System

TERMS

pulmonary function tests

arterial blood gas

oxygen saturation level

brochoscopy

QUICK LOOK AT THE CHAPTER AHEAD

Assessment of the respiratory system combines knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of the respiratory tract with data from the patient’s assessment.

General health history and specific history of respiratory functioning and/or current problem

Symptoms—Cough, secretions, dyspnea, pain

Physical assessment—Anatomic landmarks, breath sounds

Diagnostic testing—Pulmonary volumes, capacities, blood gases, radiologic procedures, laboratory tests

CASE STUDY

CASE STUDYMr. Z, a 58-year-old man, arrives at the emergency department because his wife states that he “can’t catch his breath.” Mr. Z is sitting in the chair beside the stretcher with his elbows propped on the arms of the chair. His wife is standing beside him, rubbing his arm. At first glance, he is working hard at breathing, with his shoulders stiff and high, his lips pursed on exhalation. His color is somewhat dusky, especially around the mouth. The nurse takes his vital signs and finds that his temperature is 100.8°F, his heart rate is 94 beats per minute, his respiratory rate is 32 breaths per minute, and his blood pressure is 168/92 mmHg. Using the pulse oximeter, the nurse measures the oxygen saturation (Sao2) at 88%. A round chest circumference and rib retraction are noted on chest examination. Listening with the stethoscope, the nurse notes distant breath sounds with expiratory wheezes throughout his lung fields and rhonchi in his right lung. Breath sounds are absent at the base of the right lung.

Taking a history from his wife, the nurse finds that Mr. Z has smoked two packs of cigarettes a day for 35 years. He has had “trouble catching his breath for several years,” but 2 weeks ago he had a cold, and now he can “hardly sleep because he can’t breathe.” He has no known allergies and takes atenolol, a beta-blocker, for his high blood pressure and pioglitazone for diabetes. A colleague suggests that Mr. Z be put on the stretcher and given oxygen via nasal prongs.

Important Questions to Ask

Why is Mr. Z sitting in the chair, and should he be lying on a stretcher?

What should be considered before starting oxygen therapy?

What changes might be seen on an arterial blood gas, given Mr. Z’s smoking history and oxygen saturation?

What anatomic changes cause wheezes?

What side effect of beta-blockers is making Mr. Z’s breathing more difficult?

To gain an accurate picture of a patient’s respiratory functioning, the nurse must combine knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of the respiratory tract with data from the patient’s assessment. Every patient has a

unique combination of previous medical history, current symptoms, life-style and behavior patterns, and genetic history. The goal is to gather data from the patient’s history, physical assessment, and diagnostic testing to compile a complete picture of the patient’s respiratory functioning.

unique combination of previous medical history, current symptoms, life-style and behavior patterns, and genetic history. The goal is to gather data from the patient’s history, physical assessment, and diagnostic testing to compile a complete picture of the patient’s respiratory functioning.

THE PATIENT HISTORY

THE PATIENT HISTORYMany aspects of an individual’s life impact the functioning of the respiratory system. To gather the necessary information, the nurse must begin by taking a thorough history. Gathering an accurate database provides the nurse with the information that will direct the physical assessment and guide the planning of appropriate interventions. Possible sources of information include the patient, his family or significant others, the patient’s appearance and posture, and the medical record(s).

Begin the process of taking a health history with general questions. The nurse might ask the following questions to start the assessment:

What brings you to seek health care at this visit?

What is your major problem today?

How long have you had this problem?

What makes it better or worse?

What have you tried to make it better?

How does it affect your normal daily activities?

The assessment should also include demographic data, such as age, gender, and race. Aging not only affects the functioning of the respiratory tract, but disorders such as emphysema also are more age specific. Gender can influence the incidence of certain diseases of the respiratory tract. For example, oral cancers are more common in men than in women. Race may affect such parameters as normal respiratory volumes. Caucasians have larger lung volumes than Native Americans or Asian Americans. The patient’s responses to these general questions will direct the questions in the remainder of the assessment.

Symptoms

Many respiratory problems begin with similar symptoms. Clarifying the nature of these symptoms narrows the possible problems and directs the remainder of the assessment and examination. Some common presentations

of respiratory problems include cough, sputum production, nasal secretions, dyspnea (difficult breathing), wheezing, and pain. Each presentation requires further questioning to ascertain the nature of the symptom and how it affects the patient’s functioning.

of respiratory problems include cough, sputum production, nasal secretions, dyspnea (difficult breathing), wheezing, and pain. Each presentation requires further questioning to ascertain the nature of the symptom and how it affects the patient’s functioning.

Cough

Coughing is a protective mechanism for clearing the airways. It also can be a reflexive response to irritating stimuli in the tracheobronchial tree or the larynx. The patient may describe the cough as coming in spurts (paroxysmal) or chronic, tickling, hacking, dry, or productive. Some questions might include the following:

How long has the patient had the cough?

Is the cough productive?

How would the patient describe the cough—hacking, dry, or coming in spurts?

Is the cough worse at certain times of the day or night?

Sputum

Asking a patient about sputum is an important part of the assessment. When the patient produces sputum, inquire about the daily frequency, timing during the day, and amount using a common measurement such as a teaspoon. It is important to note the color and consistency of the sputum. Specifically ask if there is blood in the sputum. If sputum production is a chronic problem, ask about recent changes in the amount and color.

Nasal Secretions

Allergies, rhinitis, infection, and irritants can cause excessive secretions. Allergies may cause thin, watery secretions and pale nasal mucosa. Infection may cause yellow to greenish secretions accompanied by reddened nasal mucosa. Some further questions might include the following:

Does the patient have problems with excessive nasal secretions?

What do the secretions look like?

Do they increase at certain times of the year?

Do plants or animals affect the amount of secretions?

Do certain “triggers,” such as pollen, dust, or food additives, make the secretions begin or increase?

Allergies, rhinitis, infection, and irritants can cause excessive secretions.

Allergies, rhinitis, infection, and irritants can cause excessive secretions.Dyspnea

Patients do not usually come in complaining of “dyspnea,” but they may describe difficulty breathing in a variety of ways. A patient may describe difficulty “catching my breath” or “I can’t seem to get enough air.” What is significant is not only the patient’s perception of the effort but also his or her tolerance for the symptom. The term dyspnea is used to describe the symptom of breathlessness and is a common presentation of respiratory problems. Dyspnea is a subjective symptom and varies from person to person. It can be graded as to its impact on the patient’s functioning using a dyspnea scale (see Table 2-1). The nurse should ask about fatigue and level of activity to gather information about activity tolerance as it relates to the dyspnea. Also note dyspnea that occurs when lying down (orthopnea) and note how many pillows the patient uses at night (“three-pillow orthopnea”).

Some more specific questions might include the following:

Was the onset abrupt or gradual?

What relieves the dyspnea—medication, cessation of activity, or change of position?

Is the breathing rapid, labored, or noisy?

Is the patient assuming certain positions to make the breathing easier, such as sitting upright (orthopnea)?

In observing the patient, is he using accessory muscles in the shoulders, neck, or abdomen to make the breathing easier?

Is breathing more difficult at certain times of the day or night?

Does shortness of breath awaken the patient at night (paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea)?

Does the patient appear anxious?

Is he gasping for breath?

Are there any signs of cyanosis (bluish-gray tinge) or pallor of the lips, mucosal lining of the mouth, inner eyelid, skin, or nail beds?

Table 2-1 Dyspnea Scale | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Dyspnea is a common presentation of respiratory problems, but it is a subjective symptom, varying from person to person.

Dyspnea is a common presentation of respiratory problems, but it is a subjective symptom, varying from person to person.Wheezing

Wheezing is a common symptom described as difficulty breathing or “catching my breath.” Wheezing is caused by airways that are constricted by swelling, secretions, or bronchoconstriction, and exhalation requires more effort. Ask the patient about when the wheezing occurs, what makes him or her wheeze, whether others can hear the wheezing, and what makes the wheezing better.

Pain

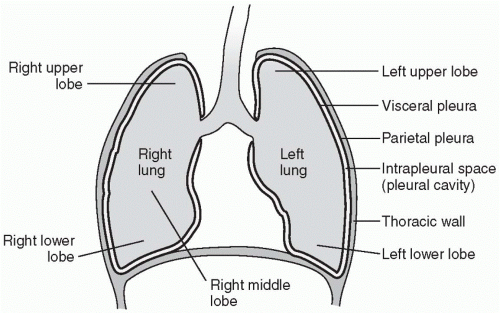

Any pain associated with breathing needs to be assessed as to location and timing in the respiratory cycle. Although lung tissue is insensitive to pain, the parietal pleura, the intercostal muscles, the connections between cartilage and bone in the thoracic cage, and the tracheobronchial tree can elicit pain. Pleuritic pain, pain caused by inflammation of the pleural membranes, is usually catching in nature and produced by movement of the thoracic cage. It is commonly unilateral and brought on by deep inspiration. Intercostal pain is transient in nature and worse during coughing. Costochondral pain occurs at the connection of the ribs and cartilage and can be elicited with pressure on the area. When assessing pain, nurses should differentiate between respiratory pain and

other pain that may be cardiac or gastrointestinal in origin. Further questions to the patient might include the following:

other pain that may be cardiac or gastrointestinal in origin. Further questions to the patient might include the following:

How would you rate the pain on a scale of 0 to 10?

Where is the pain located—beneath the sternum, in the gastric area, or in the shoulder? Does it move to another area?

What is the nature of the pain— stabbing, burning, or aching?

When does the pain occur during breathing?

Does coughing make the pain worse?

Can you point to the area where you feel the pain?

Is the pain constant, transient, or catching in nature?

How long does the pain last?

Do certain activities or movements bring on the pain, and does stopping the activity relieve the pain?

Costochondral pain occurs at the connection of the ribs and cartilage and can be elicited with pressure on the area.

Costochondral pain occurs at the connection of the ribs and cartilage and can be elicited with pressure on the area.Prior Medical History

The patient’s prior medical history contains important clues when assessing the respiratory system. A thorough listing of previous illnesses, surgeries, and their respective dates should be recorded. Questions should include the presence of general conditions, such as hypertension, heart disease, and diabetes. Systemic symptoms such as weight loss, night sweats, and fatigue provide valuable information.

Take the time to list all the medications the patient is taking: prescription, nonprescription, herbal remedies, and nutritional supplements. Nurses should obtain a detailed history of all medications for breathing problems including the method of administration and schedule or symptoms that initiate the use of as-needed medications. For example, if a patient with asthma uses an inhaler, it would be important to note if the medication is

used for relief of particular symptoms (as needed) or on a scheduled basis. Also note the frequency of as-needed medications and for what symptoms the patient decides to use these mediations. Nonprescription medications taken for breathing difficulties may include antihistamines, decongestants, nasal sprays, cough and allergy medications, inhalants, herbs, vitamins, and home remedies.

used for relief of particular symptoms (as needed) or on a scheduled basis. Also note the frequency of as-needed medications and for what symptoms the patient decides to use these mediations. Nonprescription medications taken for breathing difficulties may include antihistamines, decongestants, nasal sprays, cough and allergy medications, inhalants, herbs, vitamins, and home remedies.

If the patient has a history of asthma, the nurse should inquire about gastroesophageal reflux disease, heartburn, and indigestion.

If the patient has a history of asthma, the nurse should inquire about gastroesophageal reflux disease, heartburn, and indigestion.Specific patient responses about respiratory symptoms provide details that can direct further questioning and examination. The patient should be asked about any history of asthma, bronchitis, pneumonia, sinusitis, tuberculosis (TB), allergies, or frequent colds during the assessment. Further clarification should be obtained about allergic conditions, such as asthma, eczema, and hay fever, as well as specific allergies to dust, mold, pollen, animal dander, foods, trees, or grass. If the patient has a history of asthma, the nurse should inquire about gastroesophageal reflux disease, heartburn, and indigestion. Allergies also may be associated with asthma. Treatment for allergies, such as desensitization, should be listed with associated dates of treatment.

Any prior surgery to the upper or lower respiratory tract and the dates of surgery should be listed in the assessment. Family history of respiratory and other problems (e.g., emphysema, cystic fibrosis, lung cancer, and asthma) is important because there may be a genetic link in these conditions. The patient should be asked about recent travel and the countries that were visited, as TB is very common in Asian and Latin American countries. TB is also common among household members of an infected person, so it is important to ask about family illnesses. List the dates of the last chest radiograph, TB (Mantoux or PPD) test, vaccinations for influenza, tuberculosis, and pneumococcus, and pulmonary function tests, if appropriate.

One of the most important areas to cover in a respiratory assessment is the smoking history of the patient and his significant others. Questioning should include the use of any tobacco products, such as cigarettes, cigars, pipe tobacco, chewing tobacco, snuff, and marijuana products. Although a patient may state that he or she does not smoke, always ask

about smoking in the past. A nonjudgmental attitude about smoking should be maintained to minimize the patient’s guilt and encourage honesty. For cigarette smokers, the number of years the patient has been smoking should be ascertained and multiplied by the number of packs per day to obtain the number of “pack-years.”

about smoking in the past. A nonjudgmental attitude about smoking should be maintained to minimize the patient’s guilt and encourage honesty. For cigarette smokers, the number of years the patient has been smoking should be ascertained and multiplied by the number of packs per day to obtain the number of “pack-years.”

# years smoking X # packs per day = # pack-years

If the patient has already quit using tobacco products, the date(s) should be noted. Also, ask the patient whether anyone in the home has exposed the patient to secondhand or passive smoke. There is increasing evidence that passive smoke exposure increases the risk of asthma in children and lung cancer in nonsmoking adults. Other sources of smoke exposure include wood stoves, kerosene heaters, and fireplaces.

There is increasing evidence that passive smoke exposure increases the risk of asthma in children and lung cancer in nonsmoking adults.

There is increasing evidence that passive smoke exposure increases the risk of asthma in children and lung cancer in nonsmoking adults.Reviewing the patient’s dietary history provides valuable information about their appetite, nutritional status, eating patterns, and food allergies. Measure and weigh the patient to obtain an accurate height and weight. Review his daily dietary and fluid intake. Patients with dyspnea tend to eat smaller meals because of difficulty catching their breath when eating. Chronic dyspnea may lead to inadequate food intake, increased calorie expenditure, weight loss, and nutritional deficiencies.

Food additives have been linked to allergies and asthma. Beer, wine, restaurant salads, and many processed fruits and vegetables contain sulfites as preservatives. Sulfites may produce allergic responses in sensitive individuals, such as sneezing, urticaria (hives), shortness of breath and wheezing, chest pain or tightness, and rhinitis (excessive clear mucus from nose or “runny nose”). Tartrazine, a component of the Food, Drug,

and Cosmetic Act (FD&C) Yellow No. 5, is a food additive that has been linked to allergic responses. This is a coloring agent used in many processed foods.

and Cosmetic Act (FD&C) Yellow No. 5, is a food additive that has been linked to allergic responses. This is a coloring agent used in many processed foods.

Ask about daily fluid intake. Adequate fluid intake (six 8-oz glasses per day) is necessary for liquefying and mobilizing secretions. The daily fluid requirements of a patient can be calculated by taking his or her weight in pounds, dividing the number in half, and changing the units of measurement to ounces. For example, a woman who weighs 150 pounds should have a daily fluid intake of 75 ounces. Caffeinated and alcoholic beverages have a mild diuretic effect and extra fluids are needed to compensate for this effect. The type, amount, and frequency of alcohol intake should be determined. Excessive alcohol intake has been associated with the increased incidence of head and neck cancers.

Occupational history requires careful questioning during the assessment. The patient’s job(s) and date(s) of employment should be listed. Exposure to industrial fumes, chemicals, and dust may damage the respiratory tract. Dust from coal, stone, silicone, and asbestos may cause toxic lung injury. The classic case of occupational dust exposure and resultant disease is coal dust and black lung disease. Other occupations that involve exposure to toxic substances are jobs in dry cleaning, beauty salons, insect control, farming, and painting. Hobbies such as furniture refinishing, model airplane building, and woodworking also may expose the patient to noxious fumes or particles.

The classic case of occupational dust exposure and resultant disease is coal dust and black lung disease.

The classic case of occupational dust exposure and resultant disease is coal dust and black lung disease.Finally, other sources of respiratory problems include pets (e.g., birds, cats), time spent in the armed forces (e.g., Agent Orange exposure, Gulf War syndrome), and exposure to certain farm products (e.g., moldy wheat and hay).

PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT OF THE RESPIRATORY TRACT

PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT OF THE RESPIRATORY TRACTAfter gathering data about the patient’s health history and his current symptoms, it is time to perform a physical assessment. Provide the patient with appropriate draping in a warm, well-lit room to make the patient more comfortable during the examination. The room should be private and quiet to facilitate hearing breath sounds. The physical

examination of the respiratory tract proceeds in an orderly manner with the following steps: inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation.

examination of the respiratory tract proceeds in an orderly manner with the following steps: inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation.

Provide the patient with appropriate draping in a warm, well-lit room to make the patient more comfortable during the examination. The room should be private and quiet to facilitate hearing breath sounds.

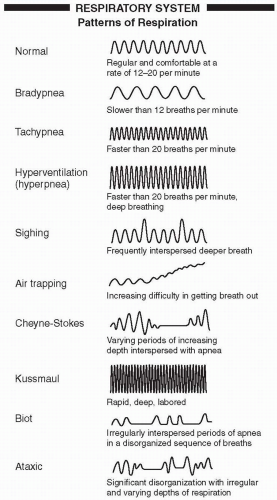

Provide the patient with appropriate draping in a warm, well-lit room to make the patient more comfortable during the examination. The room should be private and quiet to facilitate hearing breath sounds.The examination begins with a general inspection of the patient. Note the respiratory rate, rhythm, and depth. Assess the breathing pattern without the patient’s awareness so as not to make the patient self-conscious, altering the normal pattern. Count the respiratory rate for a full minute to assess the rate. The chest should move symmetrically and evenly during both inspiration and expiration. A normal respiratory rate ranges from 12 to 20 breaths per minute. A rate greater than 20 (tachypnea) may indicate hypoxemia (low serum oxygen levels), hypercapnia (high serum carbon dioxide levels), or anxiety. A low respiratory rate (less than 12 breaths per minute) is called bradypnea and may indicate central nervous system (CNS) depression, as seen with head injuries and drug overdoses. Other patterns of respiration are reviewed in Figure 2-1. As the patient breathes, the nurse should watch for the use of accessory muscles in the shoulders, neck, and abdomen or changes in posture that assist the patient in breathing. Normally, the muscles in the neck, shoulders, and abdomen are not needed for respiration, and their use indicates difficulty moving air through the respiratory passages.

A normal respiratory rate ranges from 12 to 20 breaths per minute.

A normal respiratory rate ranges from 12 to 20 breaths per minute. Normally, the muscles in the neck, shoulders, and abdomen are not needed for respiration, and their use indicates difficulty moving air through the respiratory passages.

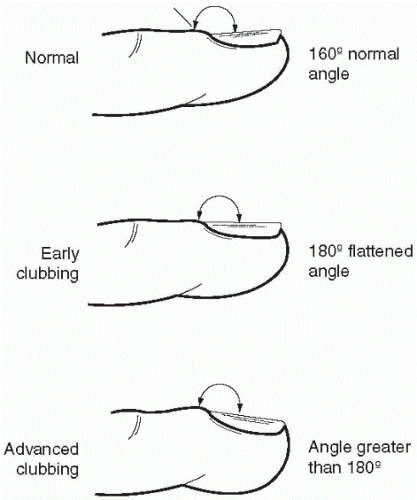

Normally, the muscles in the neck, shoulders, and abdomen are not needed for respiration, and their use indicates difficulty moving air through the respiratory passages.Check the lips, skin, and nail beds for signs of peripheral cyanosis, such as bluegray tinge or clubbing of the nails. Clubbing of the nails is a sign of long-term, impaired oxygenation. An increase in the angle between the nail bed and the digit is seen in clubbing (see Figure 2-2). Central cyanosis is better assessed by examining the mucous membranes inside the mouth and the inner

eyelid for pallor. Observe the face for nasal flaring and open-mouthed or pursed-lip breathing, which may indicate respiratory distress.

eyelid for pallor. Observe the face for nasal flaring and open-mouthed or pursed-lip breathing, which may indicate respiratory distress.

The breathing pattern should be assessed without the patient’s awareness so as not to make the patient self-conscious, altering the normal pattern.

The breathing pattern should be assessed without the patient’s awareness so as not to make the patient self-conscious, altering the normal pattern. Clubbing of the nails may be a sign of long-term, impaired oxygenation.

Clubbing of the nails may be a sign of long-term, impaired oxygenation.Nose and Sinuses

The nose and nostrils should be inspected, keeping in mind the underlying structures. The symmetry of the bony part of the nose (upper

third) and the cartilaginous part (lower two thirds) should be noted. The patient’s head should be tilted back 15° to 30°, and the position should be stabilized by putting a hand on the patient’s forehead to prevent sudden changes of position. Using a penlight and a nasal speculum, the interior of the nose, or nasal vestibule, should be inspected while not touching the septum, as it is very sensitive. The outermost portion should be skin with fine hairs followed by mucous membranes, which are normally pink and moist. The mucosa may be reddened during infection or pale during allergic reactions. The nasal septum should be inspected for deviation or perforation. The middle and lower turbinates should be visible as well. The third turbinate will not be visible because of its anatomic location. The patency of each side of the nose should be assessed by pressing on one nares to block airflow, asking the patient to inhale through the other nares, and repeating on the other side. An alcohol wipe or essence of peppermint is used to assess whether the sense of smell is intact while the patient closes his eyes and is asked to identify the smell. This determines whether the first cranial nerve, the olfactory nerve, is intact.

third) and the cartilaginous part (lower two thirds) should be noted. The patient’s head should be tilted back 15° to 30°, and the position should be stabilized by putting a hand on the patient’s forehead to prevent sudden changes of position. Using a penlight and a nasal speculum, the interior of the nose, or nasal vestibule, should be inspected while not touching the septum, as it is very sensitive. The outermost portion should be skin with fine hairs followed by mucous membranes, which are normally pink and moist. The mucosa may be reddened during infection or pale during allergic reactions. The nasal septum should be inspected for deviation or perforation. The middle and lower turbinates should be visible as well. The third turbinate will not be visible because of its anatomic location. The patency of each side of the nose should be assessed by pressing on one nares to block airflow, asking the patient to inhale through the other nares, and repeating on the other side. An alcohol wipe or essence of peppermint is used to assess whether the sense of smell is intact while the patient closes his eyes and is asked to identify the smell. This determines whether the first cranial nerve, the olfactory nerve, is intact.

Figure 2-2 Clubbing of the nails. |

The nasal septum is very sensitive—be careful not to touch it during the exam of the nasal vestibule.

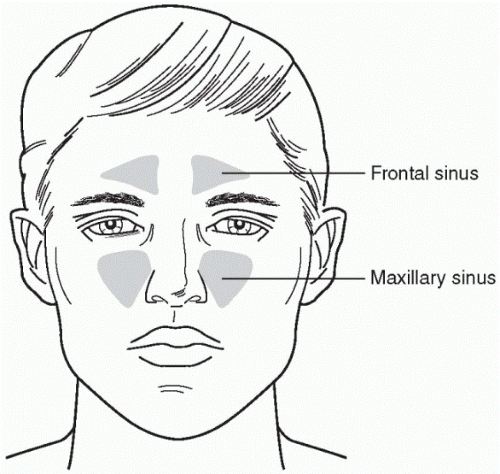

The nasal septum is very sensitive—be careful not to touch it during the exam of the nasal vestibule.Two of the four pairs of sinuses in the head, the frontal and the maxillary, are accessible for examination (see Figure 2-3). Swelling and tenderness over these sinuses is checked by palpating the area. Using the thumbs, the nurse should press firmly but gently up on the cheekbones to assess the maxillary sinuses and up on the brow bone to assess the frontal sinuses. Pain or tenderness in these areas may indicate infection (sinusitis).

Transillumination is another technique that may be used to assess the sinuses. It is an assessment technique used to evaluate the translucency of the sinuses using an outside light source. In a darkened room, a penlight is placed under the brow bone to assess the frontal sinus. A dim, red glow on the forehead indicates a normally air-filled frontal sinus. Lack of this glow may indicate a fluid or mucous-filled sinus. The same technique can be used to assess the maxillary sinuses. With the patient’s mouth opened and head tilted back, the light should be placed downward just under the inner aspect of the eye. A dim glow should be visible in the mouth on the hard palate. Although transillumination is not a definitive test, it may be

helpful in conjunction with other findings in the physical examination and history for deciding whether radiographs or computed tomography (CT scan) are needed.

helpful in conjunction with other findings in the physical examination and history for deciding whether radiographs or computed tomography (CT scan) are needed.

Mouth, Pharynx, Trachea, and Larynx

The examination begins by assessing the lips for cyanosis or pallor, sores, ulcers, cracks, or nodules. Look for signs of peripheral cyanosis on the lips that may indicate poor oxygenation. Sores or ulcers may be present with a herpes infection. Cracks in the corners of the mouth (cheilitis) may indicate nutritional deficiencies. The teeth, the quality of the dental hygiene, and the presence of dentures and other dental appliances should be noted. The patient should remove the dentures, if they are present. A penlight and tongue blade should be used to check the gums for soreness or redness that may indicate poorly fitting dentures, gingivitis, or aphthous ulcers (canker sores). Check the mucous membranes of the mouth for pallor. Because the tongue may interfere with a thorough examination, a dry 4 × 4 gauze should be used to hold the tongue and gently move it side to side to examine the mouth. The mucous membranes lining the oral cavity should be moist, and their color may vary from coral pink in light-skinned people to a brownish-pink tone in darker-skinned people. Any redness, especially along the gum line, white patches (leukoplakia), ulcerations, sores, or growths should be noted.

The mucous membranes lining the oral cavity should be moist, and their color may vary from coral pink in light-skinned people to a brownish-pink tone in darker-skinned people.

The mucous membranes lining the oral cavity should be moist, and their color may vary from coral pink in light-skinned people to a brownish-pink tone in darker-skinned people.The tongue should have pinkish papillae and be without redness or white patches. A shiny surface also is an abnormal finding on the tongue and may indicate nutritional deficiencies. With the tongue wrapped in gauze, the tongue should be moved side to side in order to examine the base of the tongue and the floor of the mouth. This is especially important for people at high risk for oral cancers, such as patients who smoke, have a history of high alcohol intake, and chew tobacco. Any redness, leukoplakia, or ulcerations should be noted.

The posterior oropharynx is visualized with a tongue blade and a penlight. While gently pressing on the middle of the tongue (not too far back, as this may cause gagging), the palate, uvula, tonsils, and posterior oropharynx should be inspected. The color and symmetry from one side to the other should be noted. Abnormal findings include swelling, exudate,

and ulceration. Enlargement of the tonsils is an abnormal finding in the adult, because tonsils should be small to nonexistent in adults. Push gently down on the tongue and have the patient say “ahhhh” or yawn to elevate the soft palate and allow visualization of the posterior oropharynx. Asymmetric elevation of the soft palate and the uvula indicates a problem with the 10th cranial nerve.

and ulceration. Enlargement of the tonsils is an abnormal finding in the adult, because tonsils should be small to nonexistent in adults. Push gently down on the tongue and have the patient say “ahhhh” or yawn to elevate the soft palate and allow visualization of the posterior oropharynx. Asymmetric elevation of the soft palate and the uvula indicates a problem with the 10th cranial nerve.

Asymmetric elevation of the soft palate and the uvula indicates a problem with the 10th cranial nerve.

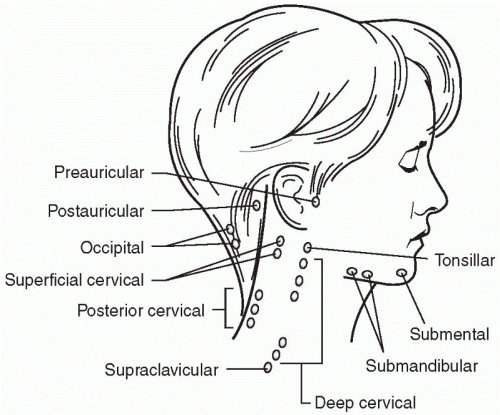

Asymmetric elevation of the soft palate and the uvula indicates a problem with the 10th cranial nerve.Inspect the neck for alignment, symmetry, nodules, or masses. Palpate the lymph nodes in the neck, assessing their size and mobility and whether they are tender (see Figure 2-4). Tender, enlarged lymph nodes usually indicate inflammation, whereas hard, fixed nodes may indicate malignancy. Palpate the trachea gently so as not to stimulate coughing or gagging. The thyroid cartilage (Adam’s apple) and the cricoid cartilage beneath it should be identified. The trachea should be uniform and midline, elevating smoothly during swallowing.

Palpate the trachea gently to prevent coughing or gagging.

Palpate the trachea gently to prevent coughing or gagging.Thorax and Lungs

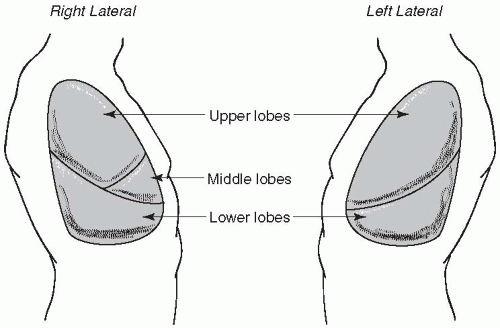

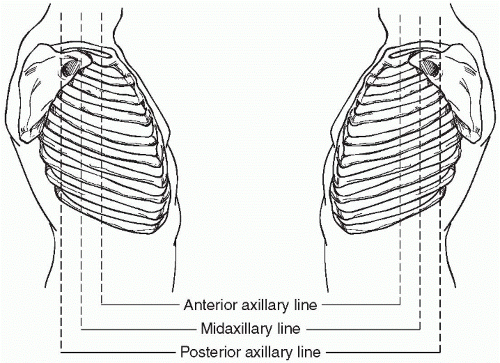

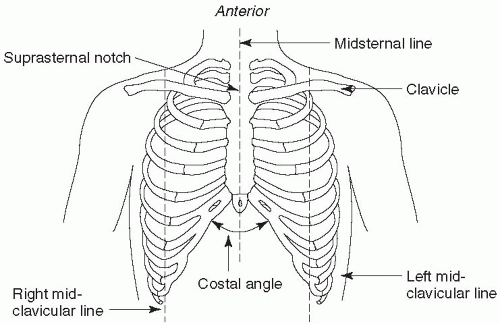

Anatomic landmarks on the thoracic cavity are useful for identifying organs within the thoracic cavity and for labeling abnormal findings (see Figures 2-5 through 2-8). The midsternal line is an imaginary line that runs vertically through the sternum. The midclavicular line runs vertically down the anterior chest wall beginning at the center of each clavicle. The anterior axillary line is another landmark that runs vertically along the anterior aspect of the chest at the anterior fold of the axilla. The posterior axillary line, which also starts at the axilla, extends vertically down the posterior chest. Also remember that each intercostal space is numbered by the rib just above it. Finally, the bases of the lungs are the lowest portions of the lungs. Anteriorly, the base of the lung refers to the lower portion of the lung beginning at the sixth intercostal space at the midclavicular line anteriorly, the eighth space laterally, and the 10th to 12th intercostal spaces posteriorly. The apex of the lung refers to the uppermost portion of the lung located above the clavicle anteriorly.

Each intercostal space is numbered by the rib just above it.

Each intercostal space is numbered by the rib just above it. Figure 2-5 Lateral landmarks of the thorax. |

Figure 2-7 Anterior landmarks of the thorax. |

The chest is examined by following the same stepwise examination: inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation. One side of the patient should be compared with the other side to assess physical symmetry and similarity of breath sounds.

The examination begins with the posterior chest, with the patient sitting with his arms folded across his chest. As the chest is uncovered,

take care to cover the unexamined areas, particularly on female patients. If the patient has difficulty sitting up, ask for assistance or roll the patient from side to side for the examination.

take care to cover the unexamined areas, particularly on female patients. If the patient has difficulty sitting up, ask for assistance or roll the patient from side to side for the examination.

The chest is examined by following the same stepwise examination: inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation.

The chest is examined by following the same stepwise examination: inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation.Inspection

Inspection of the chest begins with observing the patient’s breathing, watching for chest expansion, and the use of accessory muscles. The rate, rhythm, and regularity of the ventilations and the length of inspiration and expiration should be noted. Expiration is normally 1.5 times longer than inspiration. Prolonged expiration indicates narrowed airways or difficulty moving air out of the lungs (air trapping), as seen in emphysema. Slight retraction of the intercostal spaces is normal in thin people during quiet breathing, but any more than slight retraction indicates difficulty moving air, which may occur with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or an obstructed airway. Accessory muscles in the neck and shoulders normally are not used during breathing. The use of accessory muscles may indicate respiratory distress.

The use of accessory muscles in the neck and shoulders during breathing may indicate respiratory distress.

The use of accessory muscles in the neck and shoulders during breathing may indicate respiratory distress.A normal chest has a lateral (side-to-side) diameter, which is twice as large as the anteroposterior (front-to-back) diameter. The ratio of the lateral to anteroposterior (A-P) diameter may be increased in patients with emphysema or in infants. Some common abnormalities of the chest are seen in Figure 2-9.

♦ Barrel chest—Increased A-P diameter, giving the chest a rounded appearance with the sternum pulled out. The A-P diameter is normally increased with aging or in diseases such as emphysema.

♦ Funnel chest (pectus excavatum)—Congenital depression of the sternum that decreases the A-P diameter

A normal chest has a lateral (side-to-side) diameter, which is twice as large as the anteroposterior (front-to-back) diameter.

A normal chest has a lateral (side-to-side) diameter, which is twice as large as the anteroposterior (front-to-back) diameter.Palpation

Palpation of the thorax provides information about respiratory excursion, tender areas or masses on the chest, and the presence of tactile fremitus. Keeping the patient warm and draped, examine the posterior chest beginning with any areas that the patient reports as problematic. Palpate the chest wall gently with the palm of the hand. Note any painful areas and their anatomic location. Gentle palpation should not normally cause any pain. Note any crepitus, crackling feelings under the skin that indicate subcutaneous pockets of air. This is an abnormal condition but may occur around chest tube insertion sites.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree