Legal Context for Community/Public Health Nursing Practice

Susan Wozenski*

Focus Questions

How are basic legal issues relevant to community/public health nursing practice?

What are the sources and purposes of public health law?

Key Terms

Abandonment

Accountability

Administrative law

Agent

Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

Block grant funding

Case law

Civil laws

Civil Rights Acts

Claims-made policy

Compilation of Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA)

Contract

Criminal law

Defendant

Expert witness

General witness

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)

Informed consent

Judicial or common law

Lobbyist

Malpractice

Medical durable power of attorney

Negligence

Nurse Practice Acts

Occurrence policy

Plaintiff

Public health law

Public Health Services Act

Respondeat superior and vicarious liability

Social Security Act

Standard of care

Statute of limitations

Statutory law

Tail coverage

Tort law

Public health law

Public health law includes all laws that have a significant impact on the health of defined populations. These laws originate from multiple sources, including the U.S. Constitution, state constitutions, treaties, statutes, legislative rulings, governmental agency rules and regulations, judicial rulings, case law, and public policies. Public health law shapes public health practice through the numerous sources of law and disciplines of legal practice. Public health law also addresses the power and responsibility of government to protect the health of the population and defines the limits on the power of government to constrain the rights of individuals (Goodman et al., 2006).

Under the authority of the U.S. Constitution, federal public health law exists to promote the general welfare of society. Because states retain those powers not delegated to the federal government, much of public health law remains under state jurisdiction. As a result, there is significant variation among states regarding specific public health laws. Local jurisdictions, such as counties, cities, or townships, receive their authority from the state to enact public health laws.

Statutory law is enacted through the legislative branch of government. Laws of the legislative branches of the federal and state governments are called statutes. Similar laws of local governments are usually called ordinances. Statutes often authorize new health initiatives and appropriate tax funds to implement the law. Community/public health nurses can influence the political process by lobbying legislators and officials for or against specific statutes and ordinances.

Administrative law consists of orders, rules, and regulations promulgated by the administrative branches of governments. For example, the state board of nursing is the administrative body that regulates the practice of nursing. Other examples of administrative bodies are the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and state and local health departments. Administrative law often details the policies and procedures necessary to implement statutes. Community/public health nurses can influence the development of administrative law by advocating for orders, rules, and regulations and commenting on proposed orders, rules, and regulations during periods for public review.

Judicial or common law, also referred to as case law, is developed through federal and state courts that resolve disputes in accordance with law. Courts interpret regulations and statutes, assess their validity and create common law when decisions are not controlled by regulations, statutes or constitutions. Generally, the case before the court is compared to the facts and law in previously decided cases to determine similarities and differences in the context of current community or professional standards.

There are three levels of federal and state courts. District courts conduct trials that assess the facts of a case and determine applicable law. Appeals courts review decisions of trial courts to determine if proper procedures were followed and if the laws were interpreted correctly. Supreme courts review appeals court decisions. State courts also review state laws to determine if they are in accord with the state or federal constitutions. Federal courts can determine the constitutionality of state and federal laws. Decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court are binding in all state and federal courts.

Public health laws have played a critical role in health promotion and disease prevention. Legal interventions such as quarantine and isolation helped to stem epidemics as early as the middle ages. In the 1905 landmark case Jacobson v Massachusetts, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Massachusetts’ authority to enforce a statutory requirement for smallpox vaccination. The decision established the constitutionality of state compulsory vaccination laws when they are necessary for public health or public safety. The court indicated that the freedom of the individual must sometimes be subordinated to the common welfare and is subject to the police power of the state.

Law has been instrumental in promoting the public’s health in many areas including improved childhood immunization rates, decreased environmental health hazards, decreased dental caries, improved motor vehicle safety and workplace safety. Legal strategies have recently been used to address emerging threats from severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and influenza. In 2000, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) initiated its Public Health Law Program to assist health care professionals and policy makers in 1) accelerating and strengthening responses to bioterrorism, public health emergencies and infectious diseases, 2) using legal strategies to address obesity and other chronic diseases, 3) enhancing injury prevention strategies, and 4) facilitating partnerships and mobilizing resources to achieve public health priorities (CDC Public Health Law Program, 2011).

Community/public health nurses and public health law

Official (government) health agencies often enforce laws in addition to providing health services; nurses working in these agencies are often part of that enforcement process. In this chapter, legal issues in community/public health nursing are broadly described, and the rights of the public and clients and the rights of nurses are discussed. It is important for nurses to be aware of the laws for which they will be held accountable. Federal laws and regulations apply to persons throughout the United States, whereas state and local laws apply within the respective state and local jurisdictions. For example, state or public agencies might be protected by limited immunity statutes, whereas private agencies might not be included in these statutory protections. Facts and legal issues of case law are used to evaluate potential liability and are constantly evolving. Community/public health nurses are responsible for understanding the federal and state laws related to their practice.

Sources of law

All laws that govern society are designed to maintain order and to inform those who are accountable to the law of the expected behavior and of behavior that will not be allowed. Laws are written to carry out the wishes of the majority and to protect the rights of the minority. Laws and policies are made by legislators, as well as administrators, regulators, boards, and committees.

Environmental and public health issues are of special concern and interest to communities. Laws in these areas are usually enacted by the legislative and administrative bodies of individual states. Federal lawmakers provide the guidelines or the “umbrella” laws. States must abide by federal laws and must avoid enacting state statutes that conflict with federal guidelines. Both state and federal courts write case law or common law, which reflects society’s current beliefs regarding what best serves public welfare. Sometimes the laws within which nurses must work lend themselves to varied interpretations. In these cases, nurses and the agencies where they work should seek the opinion of their state’s attorney general for clarification.

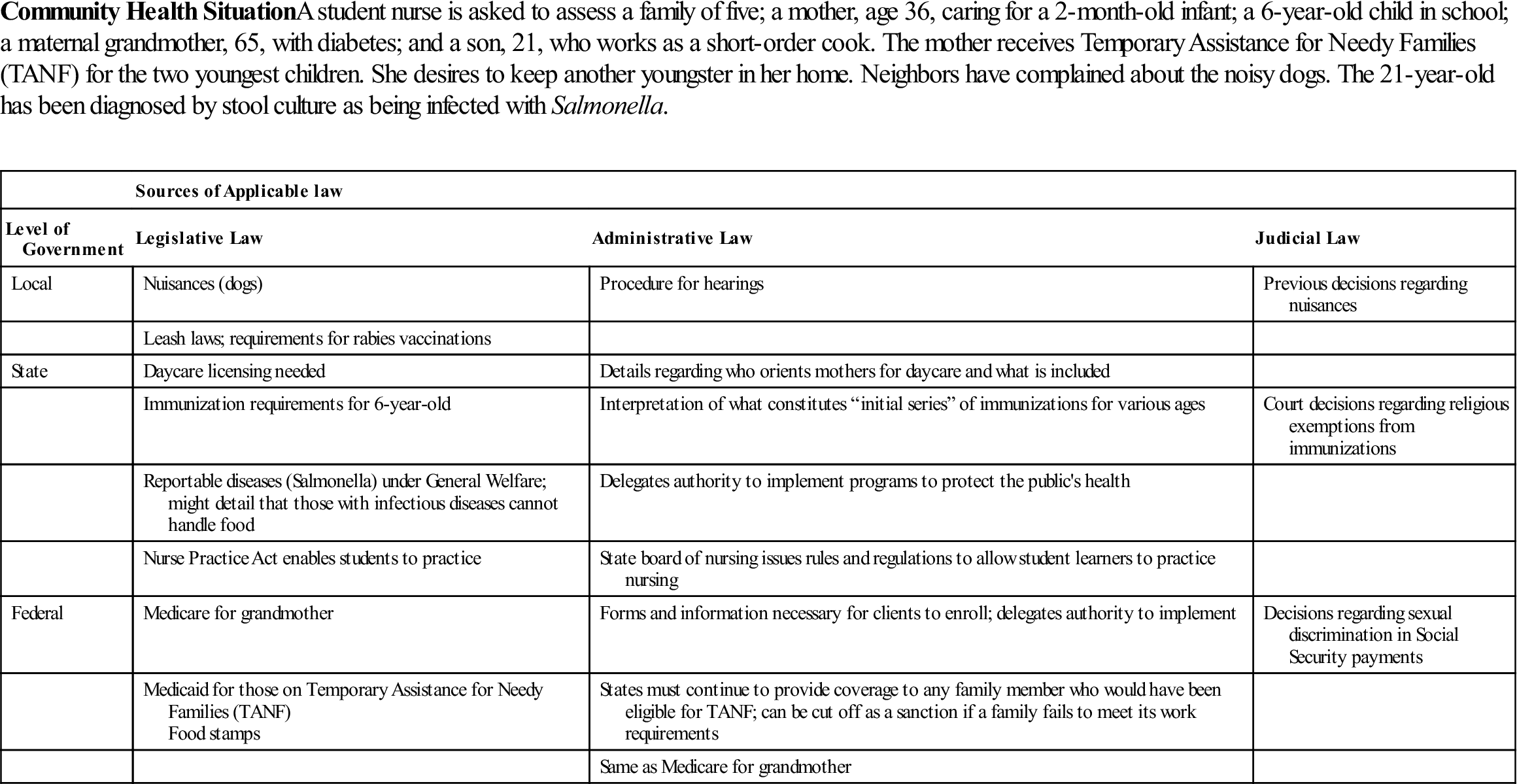

Rules, regulations, and statutes guide the community/public health nurse and are references with which the nurse must become familiar. A specific law cannot be read in isolation; a wider scope is needed to understand the nurse’s total legal responsibilities. For example, when communicable diseases are reported, both state and federal laws must be considered. Local ordinances and regulations also apply. Table 6-1 provides examples of public health law from all three levels of government that a community health nurse might encounter in caring for a family.

Table 6-1

Examples of Law Affecting Clients and Nursing Practice

| Community Health Situation |

| A student nurse is asked to assess a family of five; a mother, age 36, caring for a 2-month-old infant; a 6-year-old child in school; a maternal grandmother, 65, with diabetes; and a son, 21, who works as a short-order cook. The mother receives Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) for the two youngest children. She desires to keep another youngster in her home. Neighbors have complained about the noisy dogs. The 21-year-old has been diagnosed by stool culture as being infected with Salmonella. |

| Sources of Applicable law | |||

| Level of Government | Legislative Law | Administrative Law | Judicial Law |

| Local | Nuisances (dogs) | Procedure for hearings | Previous decisions regarding nuisances |

| Leash laws; requirements for rabies vaccinations | |||

| State | Daycare licensing needed | Details regarding who orients mothers for daycare and what is included | |

| Immunization requirements for 6-year-old | Interpretation of what constitutes “initial series” of immunizations for various ages | Court decisions regarding religious exemptions from immunizations | |

| Reportable diseases (Salmonella) under General Welfare; might detail that those with infectious diseases cannot handle food | Delegates authority to implement programs to protect the public’s health | ||

| Nurse Practice Act enables students to practice | State board of nursing issues rules and regulations to allow student learners to practice nursing | ||

| Federal | Medicare for grandmother | Forms and information necessary for clients to enroll; delegates authority to implement | Decisions regarding sexual discrimination in Social Security payments |

| Medicaid for those on Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Food stamps | States must continue to provide coverage to any family member who would have been eligible for TANF; can be cut off as a sanction if a family fails to meet its work requirements | ||

| Same as Medicare for grandmother | |||

Courtesy of Claudia M. Smith, PhD, MPH, RN-BC, former Assistant Professor, University of Maryland School of Nursing.

State and Local Statutes

There are many public health statutes enacted by state legislatures that are of concern to community/public health nurses. Statutes seek to protect the rights of both the health care provider and the consumer. Nurse Practice Acts are broad frameworks within which the legal scope of nursing practice is defined in each state. Community/public health nurses are accountable for working within this legal framework. Protection of professional practice includes avoiding compromising positions in which one is expected to practice outside the scope of nursing. Each state’s Nurse Practice Act is available on the Web as well as through employers, the state nurses’ association, and the state board of nursing.

Many states also have statutes defining malpractice actions against health care providers that pertain to community health nurses. These laws have a statute of limitations for malpractice actions that define a time frame within which a legal action must be brought. Often, the specific procedures for bringing a lawsuit against a health care provider are outlined within these malpractice statutes.

Balancing Client Rights Versus Public Health

State legislatures also enact statutes under health codes that describe laws for reporting communicable diseases, laws regarding school immunizations, and additional laws directed toward promoting health and reducing health risks in the community. An individual’s right to privacy may conflict with the public health duty to protect the general public.

Mandatory notifiable disease reporting protects the public’s health by facilitating the proper identification and follow-up of cases. Public health personnel ensure that infected individuals receive treatment; trace contacts who need vaccines, treatment, quarantine or education; investigate outbreaks; address environmental health hazards; and close facilities where spread has occurred. States periodically update their lists of mandatorily reportable diseases so it is essential to be up-to-date on your state’s legislation and regulations. The regulations that govern mandatorily reportable diseases include limits on permissible disclosures that vary from state to state. To become familiar with the relevant state and local reporting and notification requirements for disclosing otherwise confidential information, check your state and local health departments’ websites.

There are special circumstances surrounding the handling of contacts of persons with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). All clinicians are required by state law to report cases of AIDS to the local health departments. Some states require HIV infection case reporting to the state health department. Most states hold the information strictly confidential, which means that health departments are not allowed to contact sexual partners or close contacts without the permission of the infected person. Some states permit the disclosure of HIV/AIDS to certain close contacts under certain conditions. The National HIV/AIDS Clinicians’ Consultation Center maintains an updated compendium of state HIV testing laws that can assist you in becoming knowledgeable about your state’s laws (National HIV/AIDS Clinicians’ Consultation Center, 2011).

Health Records

The records required to be kept by health care providers are usually described within a state’s health code. State mandatory reporting laws usually address actions to be taken in reporting child abuse or neglect and the penalties associated with failure to report known or suspected cases of child abuse. A summary of the statutes in all 50 states mandating persons to report child abuse and neglect is available at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2011) Child Welfare Information Gateway at http://www.childwelfare.gov/systemwide/ laws_policies/state/. A growing number of states have enacted confidential communications protection for sexual abuse acts. Immunity from legal action is afforded to health care providers who, in good faith, report suspected abuse of a client to a legal authority. Statutes also define penalties for not reporting known cases of abuse.

Statutes affording protection for privileged communication of confidential information might, but do not always, include the community/public health nurse. It is important for nurses to be aware of the scope of protection in their states. In a number of states, nurse–client communications do not have the privilege of confidentiality.

Community/public health nurses must be aware of the state’s laws pertaining to family privacy matters, such as abortion, distribution of contraceptives to minors, and family violence. Their clients might seek advice on these matters and their community/public health nurse should be able to advise them. Community/public health nurses might also be asked to explain a living will statute, if one exists in their state, and the uses of a durable power of attorney (see Chapter 28). Statutes that require specific behaviors, such as the procedures for pronouncing a client dead or reporting abuse, vary among states. The board of nursing can clarify the specific expectations of community/public health nurses in that state.

Federal Statutes

Federal statutes are important to the practice of community/public health nurses. The Public Health Service and the CDC were created by Congress to coordinate the collection, sharing, and analysis of data from all of the states and the U.S. territories on certain diseases to protect the health of individuals and communities. Guidelines for dealing with legal issues pertaining to reporting requirements, such as the importance of maintaining confidentiality, are issued by the CDC. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) also provides guidelines for safe and healthy work environments.

In August of 1996, Congress passed the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Enforcement of HIPAA privacy regulations began in April 2003. HIPAA provides clients with greater control over their personal health information (e.g., a client’s condition, care, and payments for health care). HIPAA protects confidentiality by defining what privacy rights clients have, who should have access to client information, how data should be stored by providers, what constitutes the client’s right to confidentiality, and what constitutes inappropriate access to health records. Confidentiality concerns how records should be protected, and security involves measures the nurse and others must take to ensure privacy and confidentiality (Frank-Stromborg & Ganschow, 2002). Providers of care must notify clients of their privacy policy and make a good faith effort to obtain a written acknowledgment of this notification. It is the nurse’s responsibility to protect client confidentiality. Nurses need to understand both the federal HIPAA regulations and the state laws that are enacted to enforce those regulations, as well as any changes or updates to either of these. Employers affected by HIPAA are responsible for ensuring that the nurses they employ comply with the regulations.

Another example of a federal statute that must be understood by community/public health nurses is the Social Security Act and its amendments. The Medicare and Medicaid programs were enacted as amendments to Social Security and the parameters of these programs should be understood by community/public health nurses to best assist their clients (see Chapter 4). Community health clients who are eligible for either Medicaid or Services for Children with Special Health Care Needs should also be made aware of the Early and Periodic Screening Diagnosis and Treatment (EPSDT) Program. These programs are discussed in detail in Chapter 27.

In March of 2010, Congress passed the Compilation of Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), which mandates comprehensive health insurance reforms, the majority of which will be implemented by 2014. The law includes 1) new consumer protections such as prohibiting the denial of coverage for children based on preexisting conditions and eliminating lifetime limits on insurance coverage; 2) provisions for improving quality and lowering cost, such as providing free preventive care for specified screening and reducing fraud and waste in Medicare, Medicaid, and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP); 3) strategies for increasing access to affordable care such as extending coverage to age 26 for young adults on their parents’ plans, providing access to insurance for adults with preexisting conditions, rebuilding the primary care workforce, and expanding community health centers’ services; 4) provisions for holding insurance companies accountable, such as reducing premiums and strengthening Medicare Advantage; and 5) adding expanded consumer protections such as prohibiting discrimination and allowing participants in clinical trials to maintain their insurance (HealthCare.gov, 2011).

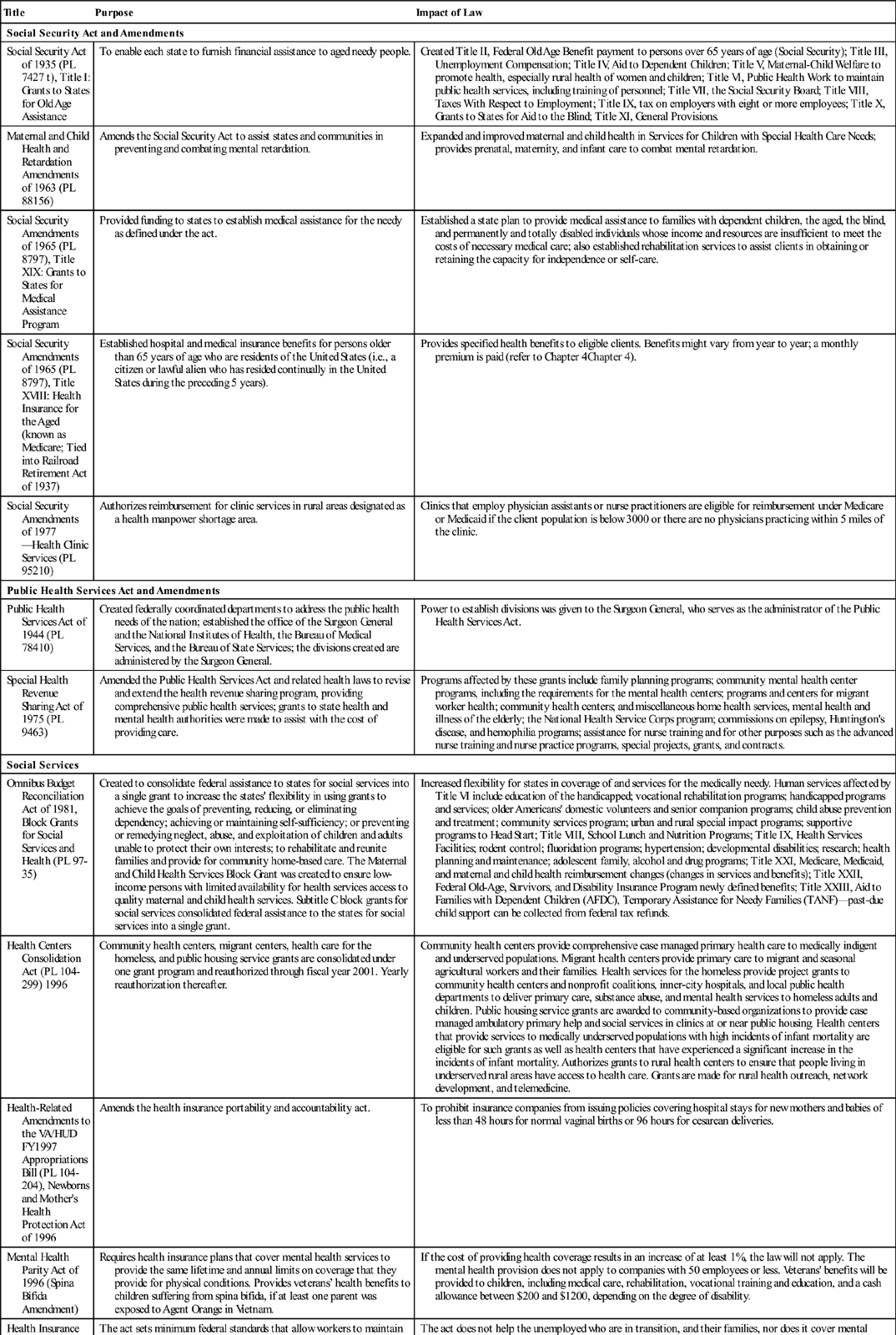

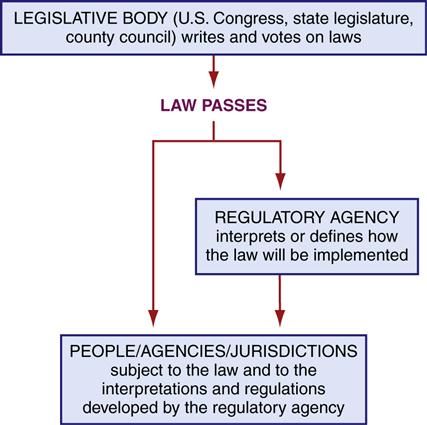

Without an adequate knowledge base or understanding of federally enacted programs, community health nurses will neglect to inform qualified clients of existing federal programs. Other examples of federal statutory law are included in Table 6-2.

Table 6-2

Federal Legislation that Influences Public Health

| Title | Purpose | Impact of Law |

| Social Security Act and Amendments | ||

| Social Security Act of 1935 (PL 7427 t), Title I: Grants to States for Old Age Assistance | To enable each state to furnish financial assistance to aged needy people. | Created Title II, Federal Old Age Benefit payment to persons over 65 years of age (Social Security); Title III, Unemployment Compensation; Title IV, Aid to Dependent Children; Title V, Maternal-Child Welfare to promote health, especially rural health of women and children; Title VI, Public Health Work to maintain public health services, including training of personnel; Title VII, the Social Security Board; Title VIII, Taxes With Respect to Employment; Title IX, tax on employers with eight or more employees; Title X, Grants to States for Aid to the Blind; Title XI, General Provisions. |

| Maternal and Child Health and Retardation Amendments of 1963 (PL 88156) | Amends the Social Security Act to assist states and communities in preventing and combating mental retardation. | Expanded and improved maternal and child health in Services for Children with Special Health Care Needs; provides prenatal, maternity, and infant care to combat mental retardation. |

| Social Security Amendments of 1965 (PL 8797), Title XIX: Grants to States for Medical Assistance Program | Provided funding to states to establish medical assistance for the needy as defined under the act. | Established a state plan to provide medical assistance to families with dependent children, the aged, the blind, and permanently and totally disabled individuals whose income and resources are insufficient to meet the costs of necessary medical care; also established rehabilitation services to assist clients in obtaining or retaining the capacity for independence or self-care. |

| Social Security Amendments of 1965 (PL 8797), Title XVIII: Health Insurance for the Aged (known as Medicare; Tied into Railroad Retirement Act of 1937) | Established hospital and medical insurance benefits for persons older than 65 years of age who are residents of the United States (i.e., a citizen or lawful alien who has resided continually in the United States during the preceding 5 years). | Provides specified health benefits to eligible clients. Benefits might vary from year to year; a monthly premium is paid (refer to Chapter 4). |

| Social Security Amendments of 1977—Health Clinic Services (PL 95210) | Authorizes reimbursement for clinic services in rural areas designated as a health manpower shortage area. | Clinics that employ physician assistants or nurse practitioners are eligible for reimbursement under Medicare or Medicaid if the client population is below 3000 or there are no physicians practicing within 5 miles of the clinic. |

| Public Health Services Act and Amendments | ||

| Public Health Services Act of 1944 (PL 78410) | Created federally coordinated departments to address the public health needs of the nation; established the office of the Surgeon General and the National Institutes of Health, the Bureau of Medical Services, and the Bureau of State Services; the divisions created are administered by the Surgeon General. | Power to establish divisions was given to the Surgeon General, who serves as the administrator of the Public Health Services Act. |

| Special Health Revenue Sharing Act of 1975 (PL 9463) | Amended the Public Health Services Act and related health laws to revise and extend the health revenue sharing program, providing comprehensive public health services; grants to state health and mental health authorities were made to assist with the cost of providing care. | Programs affected by these grants include family planning programs; community mental health center programs, including the requirements for the mental health centers; programs and centers for migrant worker health; community health centers; and miscellaneous home health services, mental health and illness of the elderly; the National Health Service Corps program; commissions on epilepsy, Huntington’s disease, and hemophilia programs; assistance for nurse training and for other purposes such as the advanced nurse training and nurse practice programs, special projects, grants, and contracts. |

| Social Services | ||

| Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981, Block Grants for Social Services and Health (PL 97-35) | Created to consolidate federal assistance to states for social services into a single grant to increase the states’ flexibility in using grants to achieve the goals of preventing, reducing, or eliminating dependency; achieving or maintaining self-sufficiency; or preventing or remedying neglect, abuse, and exploitation of children and adults unable to protect their own interests; to rehabilitate and reunite families and provide for community home-based care. The Maternal and Child Health Services Block Grant was created to ensure low-income persons with limited availability for health services access to quality maternal and child health services. Subtitle C block grants for social services consolidated federal assistance to the states for social services into a single grant. | Increased flexibility for states in coverage of and services for the medically needy. Human services affected by Title VI include education of the handicapped; vocational rehabilitation programs; handicapped programs and services; older Americans’ domestic volunteers and senior companion programs; child abuse prevention and treatment; community services program; urban and rural special impact programs; supportive programs to Head Start; Title VIII, School Lunch and Nutrition Programs; Title IX, Health Services Facilities; rodent control; fluoridation programs; hypertension; developmental disabilities; research; health planning and maintenance; adolescent family, alcohol and drug programs; Title XXI, Medicare, Medicaid, and maternal and child health reimbursement changes (changes in services and benefits); Title XXII, Federal Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance Program newly defined benefits; Title XXIII, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)—past-due child support can be collected from federal tax refunds. |

| Health Centers Consolidation Act (PL 104-299) 1996 | Community health centers, migrant centers, health care for the homeless, and public housing service grants are consolidated under one grant program and reauthorized through fiscal year 2001. Yearly reauthorization thereafter. | Community health centers provide comprehensive case managed primary health care to medically indigent and underserved populations. Migrant health centers provide primary care to migrant and seasonal agricultural workers and their families. Health services for the homeless provide project grants to community health centers and nonprofit coalitions, inner-city hospitals, and local public health departments to deliver primary care, substance abuse, and mental health services to homeless adults and children. Public housing service grants are awarded to community-based organizations to provide case managed ambulatory primary help and social services in clinics at or near public housing. Health centers that provide services to medically underserved populations with high incidents of infant mortality are eligible for such grants as well as health centers that have experienced a significant increase in the incidents of infant mortality. Authorizes grants to rural health centers to ensure that people living in underserved rural areas have access to health care. Grants are made for rural health outreach, network development, and telemedicine. |

| Health-Related Amendments to the VA/HUD FY1997 Appropriations Bill (PL 104-204), Newborns and Mother’s Health Protection Act of 1996 | Amends the health insurance portability and accountability act. | To prohibit insurance companies from issuing policies covering hospital stays for new mothers and babies of less than 48 hours for normal vaginal births or 96 hours for cesarean deliveries. |

| Mental Health Parity Act of 1996 (Spina Bifida Amendment) | Requires health insurance plans that cover mental health services to provide the same lifetime and annual limits on coverage that they provide for physical conditions. Provides veterans’ health benefits to children suffering from spina bifida, if at least one parent was exposed to Agent Orange in Vietnam. | If the cost of providing health coverage results in an increase of at least 1%, the law will not apply. The mental health provision does not apply to companies with 50 employees or less. Veterans’ benefits will be provided to children, including medical care, rehabilitation, vocational training and education, and a cash allowance between $200 and $1200, depending on the degree of disability. |

| Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (PL 104-191) (HIPAA) | The act sets minimum federal standards that allow workers to maintain their insurance coverage if they lose or leave their jobs. Medical savings accounts can be established, allowing workers with high-deductible insurance plans to set up tax-deductible savings accounts to use for medical expenses; increases the amount self-employed workers can deduct from their income taxes; gives tax breaks for long-term care insurance; and allows the chronically or terminally ill to collect benefits on their life insurance policy before death without a tax penalty. Also makes it a crime to transfer personal assets to relatives and friends, nursing homes, or others in order to qualify for Medicaid. | The act does not help the unemployed who are in transition, and their families, nor does it cover mental health. Group health plans are prohibited from discriminating against workers based on their health status or medical history. Limits to 12 months the period of time by which group health plans might exclude coverage of a preexisting medical condition (i.e., those conditions diagnosed or treated within 6 months from enrolling in a plan). Newborns and adopted children are exempted from the 12-month waiting period for preexisting conditions. A medical condition is covered within 30 days of birth, and adopted children are covered within 30 days of adoption or placement for adoption. Pregnancy is no longer considered a preexisting condition from the 12-month waiting period. Workers who were covered by group health plans are immediately eligible for coverage at a new job as long as the new employer provides health insurance to its employees. The new law does not restrict employers from imposing a waiting period for new employees to obtain health insurance, usually 3 months. However, during this period, the employee will be considered continuously covered. Requires insurers to offer individual coverage to people who lose or change jobs if the new employer does not offer health insurance to its employees. Guarantees the renewal of group and individual health insurance policies except in cases of fraud and nonpayment of premiums. |

| Provides protection for client privacy and confidentiality of medical information. Greater security over medical records and sharing of information is required. | Hospitals and other health care organizations must designate a privacy officer, provide education on HIPAA to employees regarding security of records, adopt written privacy procedures, and obtain consent from clients for most disclosures of protected health information. A minimum amount of information necessary may only be provided under HIPAA and only those with a need to know client information may access client information without consent. | |

| Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) (1996 PL 104-235) | The community-based family resources program was funded in 1997. Each state has a child’s trust fund that uses this money to make local grants for child abuse prevention programs. Child abuse prevention and treatment are the focus of this law. | Maintains a federal role in funding research, technical assistance, data collection, and information dissemination on child abuse treatment and prevention. A number of new protections for children, such as limiting delays and termination of parental rights, filing of false reports, and lack of public oversight of child protection, are also included. The act repeats the temporary child care and nursery’s program and the McKinney Family Support Center by consolidating their activities. The act also provides the Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) the ability to establish an office of child abuse and neglect. |

| The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PL 104-193) | Transformation of the welfare system, including provisions that relate to food stamps, child nutrition, child care, children’s Supplemental Security Income (SSI), child protection, child support enforcement, and immigrants. Referred to as welfare reform law, which ends 60 years of social welfare policy, completely removing many federal programs for poor families and children. | It is estimated that 2.6 million people were no longer able to rely on the federal programs previously relied upon before this welfare reform law. Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) funding was frozen through 2002 at the amount that the states received from the federal government the prior year for AFDC, emergency assistance, and jobs. TANF abolished AFDC, jobs, and emergency assistance grants (EAG) and replaced them with TANF in a block grant to the states. Under TANF, a fixed amount of federal funds is awarded to states each year regardless of need. The states must have a plan approved by HHS to determine their own eligibility requirements and the form the benefits will take. States can transfer up to 30% of TANF funds to the child care and development block grant and to the Title XX social security block grant (SSBG). Children’s SSI, which provides support to low-income children with severe mental or physical disabilities, received significant changes to the eligibility criteria. Children who lost their SSI benefits did not necessarily remain eligible for Medicaid, unless their family qualified on other criteria. All current and future legal immigrants are barred from receiving SSI and food stamps. Exempt immigrants include refugees, asylees, veterans, aliens on active duty, and immigrants who have worked 40 quarters. Future legal immigrants are barred from receiving TANF, Medicaid, and Title XX for 5 years after entering the country. All federal means tests benefits and the income of their sponsor family are deemed as part of their income when eligibility determinations are being made. Illegal or not qualified immigrants are barred from all federal public benefits, including retirement, welfare, disability, public and assisted housing, health, postsecondary education, unemployment benefits, and food assistance. Families who qualify for TANF no longer have a guaranteed legal right to child care. However, TANF prohibits states from penalizing parents of children under 6 year of age who are single and cannot find accessible child care. |

| Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (PL 105-33) | To expand access to health care by Medicare beneficiaries. | Provides direct Medicare reimbursement to advanced practice nurses, specifically nurse practitioners (NPs) and clinical nurse specialists (CNSs) practicing in any setting. |

| State Children’s Health Initiative Program (SCHIP) (2001) | To encourage health insurance coverage for children of needy families. | States that develop health insurance plans that provide health insurance coverage to the children of families with low incomes are provided matching federal funds to support these health plans. |

| Children’s Health Insurance Reauthorization Act (2009) | Expanded health care program to 4 million children and pregnant women, including legal immigrants without a waiting period. | |

| Compilation of Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010) (PL 111-148) | To mandate comprehensive health insurance reforms. | Designed to improve quality and affordable care for all Americans to improve access to public programs such as Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and maternal and child health services, to improve the quality and efficiency of health care, to prevent chronic disease and improve public health, to improve and increase the health care workforce, to increase transparency and program integrity, to improve access to innovative therapies, to establish a national voluntary insurance program for purchasing community living assistance services and support, and to institute revenue offsetting provisions. |

Data from the U.S. Code, Congressional and Administrative News. (1935, 1937, 1944, 1963, 1965, 1975, 1977, 1981). St. Paul, MN: West Publishers; Center for Community Change. (1996). Less money, fewer rules, more power to the state. The 104th Congress, Public Policy Department; U.S. Government Printing Office. HIPAA, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Retrieved February 8, 2012 from http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-104publ191/content_detail.html; andHealthCare.gov. (2011). Retrieved July 27, 2011 from http://www.healthcare.gov/law/introduction/index.html.

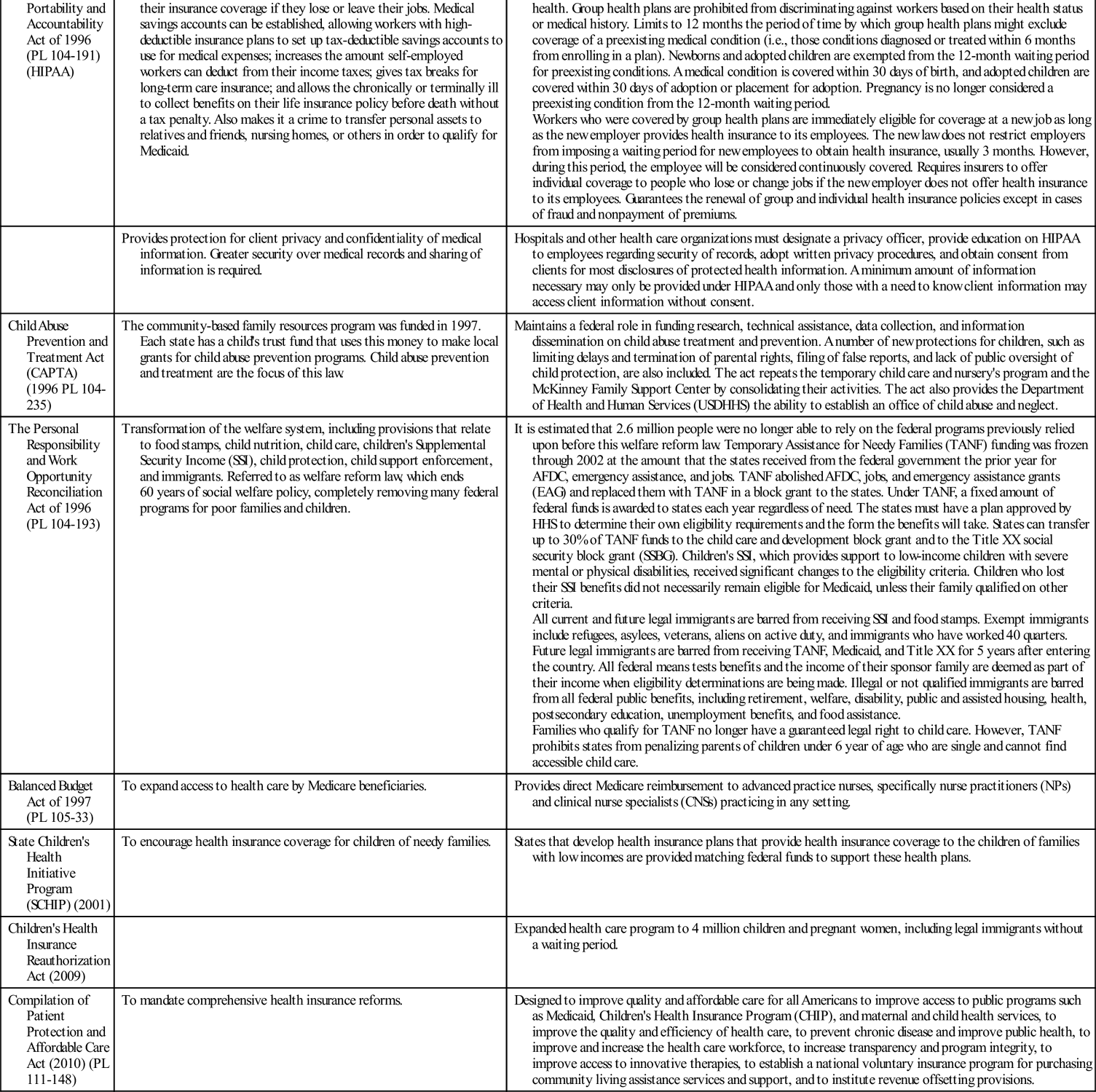

Administrative Rules and Regulations

Rules and regulations are established by administrative bodies of government, such as licensing boards and regulatory agencies. Administrative bodies, including state nursing boards and health departments, are composed of experts in the field who are considered to be better prepared than the average layperson to make decisions regarding the specific rules and regulations for safe practice. The authority to promulgate rules and regulations is delegated to the administrative body by the legislative branch of government—Congress for federal rules and regulations and state legislatures for state rules and regulations (Figure 6-1).

Often the rules and regulations enacted by the administrative body are intended to provide the details for implementation or clarification of a broader statute enacted by the legislature. As an example, the Nurse Practice Act in most states provides broad guidelines defining the scope of nursing practice. The more specific rules and regulations promulgated by the state nursing board provide necessary details to give guidance to nurses in the state. Administrative rules and regulations cannot conflict with the statute they seek to interpret, yet the details that the rules and regulations provide can be very powerful in defining the scope of practice of nursing in the state. Regulations also provide guidelines for how to work within the health care system (e.g., how to submit an application to receive Medicare or Medicaid and even who may apply).

Administrative lawmaking, the promulgation of rules and regulations, is usually preceded by notice of the proposed rule or regulation. Those who will be affected are given an opportunity to provide input. For example, because nurses are affected by the state board of nursing rules and regulations, they may provide input in writing or attend a hearing specifically held to discuss the proposed rule or regulation.

Administrative law bodies are often empowered to revoke or suspend professional licenses. Charges involving suspected violations of the Nurse Practice Act or of administrative rules or regulations, or other charges brought against a nurse related to professional practice, are heard and decided by the state board of nursing. The decision of the administrative rule-making body might be appealed to the state court system. If a community/public health nurse is asked to perform a procedure that she or he believes is beyond the scope of nursing practice, the nurse or supervisor can receive clarification by requesting a declaratory ruling from the state board of nursing.

Refusal to perform questionable duties until clarification is received should be considered reasonable and safe practice, not insubordination.

Examples of administrative rules and regulations that protect the public are those promulgated by OSHA. The occupational safety of workers is central to maintaining a healthy work force and employers must comply with the regulations that define a safe and healthy work environment. For example, employers of health care workers are required to provide protective equipment and conduct in-service education about universal precautions to prevent the spread of HIV and hepatitis B virus.

Judicial or Common Law

Common or judicial law is based on common usage, custom, and court rulings called case precedents. Case precedents are useful for interpretation of statutory language and for comparative purposes. The facts of a case at trial are compared with cases previously ruled on and evaluated for similarities and differences. Rulings may also be based upon the testimony of witnesses, external standards, and common sense. Case law reflects the changes in society’s views; cases might be overturned or overruled and, therefore, might not be safely relied on as the law in that state. Relying on the expertise of an attorney who practices in health care law is recommended when engaged in litigation.

The cases of most interest to community/public health nurses involve circumstances that can be applied to the practice of community/public health nursing. For example, court decisions might provide support for exemptions from immunizations based on a person’s religious beliefs or the parameters of obtaining informed consent when working in a community health setting. Nurses need to understand the specific facts of a case to safely assess their own situation or likelihood of liability. The Case Study in this chapter, which focuses on a nurse’s response to a child’s asthma attack in school, demonstrates liability risks for school nurses.

Roles that the community/public health nurse assumes become legally binding duties and must be undertaken responsibly. Some community/public health nurses might be required to perform laboratory tests such as phenylketonuria (PKU) testing. Failure to adequately inform a client or guardian or performing a test improperly might lead to litigation. Nursing judgments, such as the assessment of an individual’s condition and the documentation of signs and symptoms supporting the nursing inferences, might be critical in deciding the severity of the illness or describing adverse reactions to prescribed treatments. For example, when the nurse provides home health care to ill persons, blood pressure readings that are outside normal parameters must be reported to the physician or nurse practitioner in charge of the case. The community/public health nurse might be the only person who has direct contact with the community health client, which makes communication between the health department or home care agency, physician or other members of the health care team, and the community/public health nurse critical. The importance of accurate and timely communication has been tested in many legal cases involving nurses.

Liability issues in health care have changed significantly over the past 50 years. In the earliest cases, nurses were considered employees of physicians, hospitals, health departments, etc., which were responsible for the actions of their employees, not as a professional group with its own standards and accountability. The defense strategies of respondeat superior and vicarious liability (i.e., being responsible for another’s actions) transferred liability from the nurse to the physician or the health department or hospital; nurses were not viewed as responsible for their actions or inactions. Now courts recognize the independent status of nurses as professionals and hold nurses individually accountable for their professional actions.

Supervisory liability is one of the few instances in which vicarious liability occurs in current case law. As a supervisor of nurses, nurse’s aides, or licensed practical nurses in an agency, a community/public health nurse must not delegate tasks to these workers that are beyond the scope of their knowledge base or the legal scope of their practice. If a person the community/public health nurse supervises harms a client while providing care, the community/public health nurse’s professional judgment when delegating such tasks will be assessed to determine whether the nurse’s action was reasonable. Most common law issues in nursing involve the torts of negligence or malpractice, which are discussed in this chapter’s section on civil laws.

Community/public health nurses might find themselves involved in the court process in one of several roles. As a defendant, the nurse stands accused of causing harm to another; as an expert witness, the nurse testifies as to the standard of care in community/public health nursing; and as a general witness, the nurse testifies regarding the specific facts at issue in a given case. Community/public health nurses currently enjoy greater autonomy than many other nurses, which makes professional accountability even more critical. Court cases relating to the practice of community/public health nursing will most likely increase as a result of the shortened length of patient stays in acute care facilities, which translates into increasingly complex care being delivered to these patients, and more care being delivered in community settings.

Attorney General’s Opinions

In many states, the attorney general is the official legal counselor for public agencies, including health departments. Questions pertaining to the legality of procedures or the scope of nursing practice within the state can be clarified with the attorney general. The state attorney general provides both informal and formal opinions. If the legal issue is of such concern that the nurse or agency believes the liability risks are great, a formal written opinion should be requested.

The state attorney general’s opinions provide guidelines based on both statutory and common law interpretations. The attorney general’s office evaluates the written law, including its legislative history, and provides an opinion as to how the law should be applied. If a legal issue arises and the community/public health nurse has an attorney general’s written opinion offering an interpretation of a particular issue or statute, the court will most likely view the nurse or the agency as having acted reasonably and responsibly in seeking clarification of what is appropriate. If the nursing action conforms with the attorney general’s opinion, the court will usually consider this favorably on behalf of the nurse or agency named as a defendant in a lawsuit.

The basic underlying principle is that a nurse should be able to rely on the professional advice of legal counsel. An attorney general’s opinion might differ from a second opinion from the same office or an opinion from another attorney at a later date. Highly controversial issues, such as abortion and contraception for adolescents, may be influenced by political concerns and may receive differing interpretations by different individuals in the same office at different times.

Contracts

A contract is an agreement between two persons who have the legal capacity and are competent to join into a binding agreement that is recognized under the law. Contracts protect the rights of both clients and nurses. Community/public health nurses must be aware that promises made to clients that are meant to be reassurances might be interpreted by clients as binding promises of outcomes. It is best to avoid making promises about things that are outside one’s control. There are situations in community/public health nursing in which a formal contractual agreement is necessary. If one agency agrees to provide services to another agency, it is wise to have the understanding in writing. The purpose of a written contract is to provide evidence of what the parties are mutually agreeing to do.

Employment contracts are an important issue for all nurses. The customary practice in nursing has been to hire a nurse without a written contract. In this situation, the policies and procedures describing the duties and responsibilities of the community/public health nurse are often the agency’s legally binding employment agreement. If an employment agreement specifies duties that are beyond the scope of nursing practice in the state, nurses should not provide these services. The fact that an agency might require a community/public health nurse to perform a procedure will not protect the nurse as an individual if this practice is found to be outside the scope of nursing as defined by the state’s Nurse Practice Act. The law will overrule any agency policy or procedure. In a Texas case, a nurse testified that she was following the physician’s direction and the agency’s policy. The court ruled that the state’s Nurse Practice Act was the rule of law the nurse should be following. The fact that she relied on what the physician or her employer told her to do was an insufficient defense (Lunsford v Board of Nurse Examiners, 1983). Nurses who question whether they should perform some of the services required of them by their community health agency should bring these concerns to the attention of their supervisor. It may also be appropriate to request a declaratory ruling from the board of nursing to determine whether the practice in question is within the scope of nursing.

Before signing an employment or other contract, the nurse should read the contract carefully. If a person signs a contract without reading it, the court will not view this favorably. When establishing a client contract, the community/public health nurse must make certain that the terms of agreement are written out before asking the client for a signature.

Classification of laws and penalties

Laws are enacted by state legislatures or Congress, as described previously, and specific categories of laws have associated penalties. The authorities or bodies that enforce the laws are also unique to the particular classification of the laws, whether criminal or civil.

Criminal Laws

The laws that constitute the criminal code (criminal law) are written for the protection of the public welfare. For this reason, when a case is brought under the criminal code, the defendant faces society, represented by a prosecutor, instead of an individual plaintiff. Criminal cases are prosecuted by the government. The penalties attached to criminal violations tend to be more severe and include the possibility of incarceration. Examples of potential violations of the criminal code in community/public health nursing include the situation in which the nurse believes that her or his own judgment about the worth of a person’s life is the correct one and acts to hasten the death of that person. The criminal code refers to this behavior as either murder or manslaughter. There has been an array of cases involving nurses who saw themselves as “angels of mercy” and hastened death in hospitals and long-term care facilities.

A community/public health nurse who recklessly endangers others can be criminally prosecuted. Some states are becoming more willing to use criminal law rather than relying on state board sanctions to punish professional misconduct. For example, nurses in Denver were prosecuted for negligent homicide in the case of a fatal drug overdose in addition to facing civil prosecution for malpractice and state board sanctions. Laws relating to theft and other property violations are also found under the criminal code. Laws that prohibit abuse of children or elderly people are criminal laws written to protect these segments of the public. Most states have statutes that require nurses to report suspected child or elder abuse (see Chapter 23).

It is not unusual to read about a nurse who has been convicted of a crime and later discover that the state board of nursing has scheduled a hearing to consider whether the nurse’s license should be revoked or suspended. Certain crimes can be grounds for the loss of one’s professional license if the behavior can be reasonably connected to the professional responsibilities of the nurse. Violations involving substance abuse might result in suspension of a community/public health nurse’s license until proof is offered that the nurse is no longer using the substance in question. Because nurses are in a position to affect the health and safety of consumers, nurses’ personal habits and behavior are linked to their professional licensure.

A conviction for a criminal violation might result in imprisonment, parole, the loss of privileges (such as a nursing license), a fine, or any combination of these penalties. If a community/public health nurse becomes aware of illegal activity in a client’s home, it would be wise for the nurse to speak to the nursing supervisor to determine whether reporting the illegal activity is mandated by law. The nurse must exercise judgment regarding the threat posed to society versus the impact on the nurse-client relationship.

Civil Laws

Civil laws are written to regulate the conduct between private persons or businesses. A private group or individual might bring a legal action for a breach of a civil law. This private group or individual is called the plaintiff. The person charged with violating a law or legal right is called the defendant. The court’s ruling may result in a plan to correct the wrong between the two parties and might include a monetary payment to the wronged party, commonly known as damages. The penalties for most civil wrongs do not include incarceration. Some civil cases might discover violations of the criminal laws, which might then lead to criminal penalties.

Community/public health nurses most often work autonomously without the opportunity for on-site immediate collaboration with other nurses or members of the health care team. Nurses as professionals are accountable for the nursing judgments they make. Consumers see nurses as trustworthy experts in their field and rely on what nurses tell them. However, if a client is harmed because of a nurse’s action, inaction, or incorrect advice, the nurse can be held legally accountable for the resulting injury.

Most cases involving nurses fall under the domain of tort law. A tort is defined as civil wrong committed or omitted by a person against a person or property of another that leads to injury to that person, property, or reputation. Tort law covers both intentional and unintentional torts. An intentional tort is found when an outcome is planned, whereas an unintentional tort involves accidental or unintended behavior. Negligence and malpractice are considered unintentional torts. Negligence is based on the principle of reasonable care and is the failure to do what a reasonable person would do under similar circumstances, which results in an injury. Malpractice is a specific type of negligence. Malpractice goes beyond the reasonable care standard and recognizes the specialized training and licensure of members of a profession. Malpractice is the failure to exercise the training and skills normally provided by other members of the profession, which results in harm to the client. Many cases result from failure to adhere to standards of care. To be found guilty of negligence or malpractice, a nurse must have a duty to the client, the breach of which has injured the client. The commissions or omissions of the nurse must have directly caused the injury.

If a nurse unintentionally harms a client, a malpractice or negligence case under the civil statutes would be the most likely result. If a community/public health nurse intentionally plans an injurious outcome, a criminal case could result.

The number of lawsuits alleging negligence or malpractice brought against nurses has been increasing (National Practitioner Data Bank, 2005). However, lawsuits against nurses accounted for only 9.2% of all malpractice suits in 2006, and malpractice payments involving nurses account for only 2.1% of all malpractice payments (National Practitioner Data Bank, 2006). Most claims brought against registered nurses involve monitoring, treatment, and medication errors. A significant number also involve obstetrics and surgical errors.

Malpractice cases involving nurses often involve the following circumstances (Phillips, 2007, Eskreis, 1998):

• Improper treatment or negligent performance of a treatment

• Inadequate assessment and intervention in monitoring situational changes

• Failure to follow prescribed orders or agency protocols, policies, and procedures

• Working while impaired whether by inadequate sleep or controlled substances

• Inappropriate delegation or supervision

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree