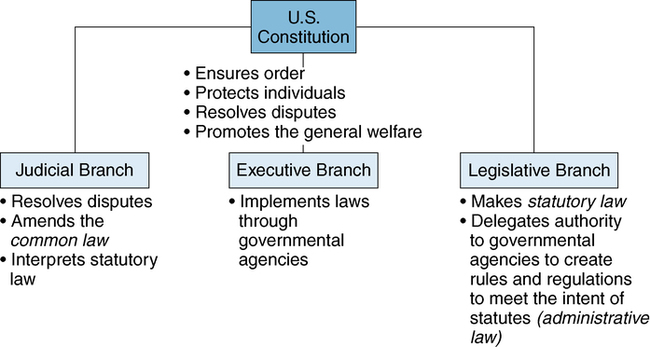

After studying this chapter, students will be able to: • Describe the components of a model nurse practice act. • Discuss the authority of state boards of nursing. • Explain the conditions that must be present for malpractice to occur. • Identify nursing responsibilities related to delegation, informed consent, and confidentiality. • Explain the legal responsibilities of nurses to enforce professional boundaries, including the use of social media. • Describe strategies nurses can use to protect their patients, thereby protecting themselves from legal actions. Professional nursing has many complex and intertwined relationships in the legal arena that are important to identify and understand. The legal aspects of nursing are an area that is both extremely important and constantly changing. Schools of nursing and continuing education providers offer “Nursing and the Law” courses that are very popular among nurses. This chapter highlights key legal issues that affect professional nurses. Maintaining a working knowledge of the law as it relates to professional nursing practice is even more critical now, in a time of great change in health care, as roles and practice settings change and expand. Nurses who do not understand and stay current with the changes in laws and regulations that govern nursing practice may find themselves with an increased exposure to liability, disciplinary measures, fines, or litigation (Aiken, 2004). This chapter will give you a beginning perspective on the various ways that nursing practice is affected by the legal system. It is common for nurses, especially early in their careers, to be very concerned about “breaking the law” regarding nursing practice or to misinterpret the meaning and purposes of laws. Laws are actually protective of both nurses and the patients for whom they are providing care. Chapter opening photo from Photos.com. The Constitution established a government in which the balance of power was divided among three separate but equal branches: (1) the executive branch, charged to implement law, and which includes the Office of the President at its highest level; (2) the legislative branch, charged to create law, and which includes the U.S. Congress and other regulatory agencies that set law; and (3) the judicial branch, charged to interpret law, and which includes the Supreme Court and federal court system (Figure 4-1). Laws are further categorized as either civil or criminal. Civil law recognizes and enforces the rights of individuals in disputes over legal rights or duties of individuals in relation to one another. In civil cases, the party judged responsible for the harm may be required to pay compensation to the injured party. In contrast, criminal law involves public concerns regarding an individual’s unlawful behavior that threatens society, such as murder, robbery, kidnapping, or domestic violence. The criminal court system both defines what constitutes a crime and also may mandate specific punishments (Aiken, 2004). Individuals convicted of criminal charges are punished, usually through the loss of some degree of their freedom, ranging from probation to imprisonment. They may also be required to pay fines. Administrative cases result when a person violates the regulations and rules established by administrative law, such as when a nurse practices without a valid license or beyond the scope of nursing practice. Punishment may involve revocation or suspension of one’s nursing license or being placed on probation. In egregious cases, imprisonment may be required, especially if malicious intent or gross negligence is demonstrated. 1. Defines the practice of professional nursing 2. Sets the minimum educational qualifications and other requirements for licensure 3. Determines the legal titles and abbreviations nurses may use 4. Provides for disciplinary action of licensees for certain causes In many states, nurse practice acts also define the responsibilities and authorities of the SBN (National Council of State Boards of Nursing [NCSBN], 2006). Thus the nurse practice act of the state in which nurses practice is statutory law affecting nursing practice within the bounds of that state. For example, a registered nurse (RN) who works in Virginia practices under the nurse practice act of Virginia, although the nurse’s home address may be in Maryland. Maryland’s state board of nursing has no jurisdiction over the nurse’s practice as long as the nurse is working in Virginia. Because of the importance of practice acts to professional nurses, both the American Nurses Association (ANA) and the NCSBN have developed suggested language for the content of state nurse practice acts. The ANA’s Model Practice Act was published in 1996 to guide state nurses associations seeking revisions in their nurse practice acts (ANA, 1996). The guidelines encourage consideration of the many issues inherent in a nurse practice act and the political realities of each state’s legislative and regulatory processes. Through this document, the ANA recognizes the great importance of the nurse practice act and urges that the following content be included: 1. A clear differentiation between advanced and generalist nursing practice 2. Authority for boards of nursing to regulate advanced nursing practice, including authority for prescription writing 3. Authority for boards of nursing to oversee unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP) 4. Clarification of the nurse’s responsibility for delegation to and supervision of other personnel 5. Support for mandatory licensure for nurses while retaining sufficient flexibility to accommodate the changing nature of nursing practice The NCSBN’s Model Nursing Practice Act and Model Nursing Administrative Rules (2011a) is a comprehensive documents developed to guide individual states’ development and revisions of their nurse practice acts. The NCSBN began development of model regulations in 1982. The NCSBN describes the current model, in its fourth major revision, as both a standard toward which states may strive and a reflection of the current and changing regulatory and health care system environments. Discussions over the past two decades at the national level, facilitated by both the NCSBN and ANA, have brought a national perspective on nursing regulation to the state level, fostered dialogue and the development of more consistent standards across state lines, and provided increased protection for the public (Mikos, 2004). 1. Executive, with the authority to administer the nurse practice act 2. Legislative, with authority to adopt rules necessary to implement the act (note that rules are different from laws, which are made by the state’s legislative body) 3. Judicial, with authority to deny, suspend, or revoke a license or to otherwise discipline a licensee or to deny an application for licensure Historically, the nursing profession has demonstrated a commitment to the rehabilitation of nurses whose practice is impaired by mental health issues or substance abuse. The ANA first published a recommendation that a Nursing Disciplinary Diversion Act be implemented by states through their boards of nursing (ANA, 1990). Later, the NCSBN published Substance Use Disorder in Nursing, a comprehensive resource to assist with the evaluation, treatment, and management of nurses with a substance problem (NCSBN, 2012). Nurses are estimated to misuse drugs and alcohol at approximately the same rate—10% to 15%—as the general population; however, only a small percentage of nurses are disciplined each year for substance abuse. The goal of SBNs is to return to safe practice those nurses who have been identified as having a problem with drugs and/or alcohol use. This is accomplished through the use of interventions that have evidence of effectiveness. Individuals who have successfully completed their basic nursing education from a state-approved school of nursing are eligible to sit for the licensing examination. The nurse licensure examination for RNs is the National Council Licensure Examination for Registered Nurses (NCLEX-RN®). It is administered by computerized adaptive testing at various testing centers across each state, at a time scheduled by the test-taker. The NCLEX-RN®, which is updated periodically, tests critical thinking and nursing competence in all phases of the nursing process. The current test plan can be found at the NCSBN website (www.ncsbn.org/1287.htm), where you can download a comprehensive document available as a .pdf file. Test-takers who are not successful in passing the NCLEX-RN® typically may take the examination again after paying the examination fees. Passing rates for graduates of different nursing schools are published online on SBNs’ websites. Passing rates for first-time test-takers reflect the quality of the education that specific programs are providing. Schools with consistently high scores among their first-time test-takers are providing excellent education and preparation of their graduates for professional nursing practice. Most if not all states include the first-time pass rate for each nursing school in their respective states. You can likely find your own school’s first-time pass rate on your SBN’s website. Because the United States has a mobile society, a regulatory approach known as a Nurse Licensure Compact (NLC)—a mutual recognition model of licensure—was developed by the NCSBN in 2000. The NLC has been adopted by 24 states, with 6 more states having pending legislation (as of mid-2012). The NLC was developed to improve mobility of nurses, while still protecting the public health, safety, and welfare. Mobility occurs in travel nursing, in crossing state lines from one’s home to one’s workplace, in the telehealth practices (being physically present in one state while providing nursing care to a patient in another state through digital technology), and simply moving to another state for personal or career purposes. Nursing workforce mobility during national or regional disasters is also increased (Hellquist and Spector, 2004). Each state that wishes to participate in the compact must pass legislation enabling the board of nursing to enter into the interstate NLC. Utah, Texas, and Wisconsin were the first states to implement the compact on January 1, 2000. Nurses licensed in any state that has implemented the compact can practice in their own states, as well as in any other compact state without applying for licensure by endorsement. A nurse who has changed permanent residence from one compact state to another may practice under the license from their former state of residence for up to 30 days, which starts on the nurse’s first day of work. The license in the new state of residence will be granted under endorsement rules if the nurse is in good standing with the SBN of the state from which the nurse is moving. This means that a nurse moving between compact states does not have to delay working as a nurse until a new license is granted. Updated information about states participating in or seeking legislation to participate can be found at www.ncsbn.org/nlc.htm. Application of the compact model to advanced practice nurses is under discussion. Exploration of the global perspective on nursing regulation is currently on the NCSBN agenda (Apple and Spector, 2005). Based on a demand from nurses educated abroad, the NCSBN began administering the NCLEX-RN® internationally to otherwise qualified nurses applying for U.S. licensure in January 2005. The recruitment of nurses from outside the United States, particularly from poorer nations with their own high health care demands, is controversial (Dugger, 2006), with both legal and ethical considerations. Chapter 5 contains a fuller discussion of the significant issues surrounding recruiting nurses from other countries to practice in the United States. Malpractice is negligence applied to the acts of a professional. In other words, malpractice occurs when a professional, for example a nurse or a physician, fails to act as a reasonably prudent professional would have acted under the same circumstances. Malpractice does not have to be intentional—that is, the professional did not mean to act in a negligent manner. Malpractice—that is, professional negligence—may occur in two ways: by commission—doing something that that should not have been done—and by omission—failing to do things that should have been done (Box 4-1). A patient who brings a claim of malpractice against a nurse (or other professional) is known in the legal system as the plaintiff. The nurse becomes the defendant. Getting a malpractice case to be pleaded in front of a judge and jury is a very long process and is actually very unlikely to get this far. Many times malpractice cases are settled out of court, meaning that the outcome is negotiated between attorneys for the plaintiffs and defendant(s) (Critical Thinking Challenge 4-1). “Prevailing” is an important qualifier. As practice changes and develops, standards of care change accordingly. The issue in malpractice cases is the standard of care that prevailed—or was in effect—at the time the negligent act occurred. What may be considered negligent now may not have been considered negligent at the time. The standard of care that prevailed at the time is key and is ascertained through expert witness testimony; documents, including national standards of nursing practice; the patient record; and other pertinent evidence such as the direct testimony of the patient, the nurse, and others. Box 4-2 illustrates the presumed failure of an RN to meet the prevailing standard of care. 1. The professional (nurse) has assumed the duty of care (responsibility for the patient’s care). 2. The professional (nurse) breached the duty of care by failing to meet the standard of care. 3. The failure of the professional (nurse) to meet the standard of care was the proximate cause of the injury. Croke (2003) conducted a review of more than 350 trial, appellate, and supreme court case summaries from a variety of legal research sources and analyzed 253 cases that met the following criteria: A nurse was engaged in the practice of nursing as defined by his or her state’s nurse practice act; a nurse was a defendant in a civil lawsuit as the result of an unintentional action (no criminal cases were considered); and a trial was held between 1995 and 2001. This review identified six major categories of negligence resulting in malpractice lawsuits against nurses: failure to follow standards of care, failure to use equipment in a responsible manner, failure to communicate, failure to document, failure to assess and monitor, and failure to act as a patient advocate. More details of Croke’s analysis are presented in Box 4-3.

Legal aspects of nursing

![]() To enhance your understanding of this chapter, try the Student Exercises on the Evolve site at http://evolve. elsevier.com/Black/professional.

To enhance your understanding of this chapter, try the Student Exercises on the Evolve site at http://evolve. elsevier.com/Black/professional.

American legal system

Nursing as a regulated practice

Statutory authority of state nurse practice acts

Executive authority of state boards of nursing

Licensing powers

Licensure examinations

Nurse licensure compact

Legal risks in professional nursing practice

Malpractice

Legal aspects of nursing

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access