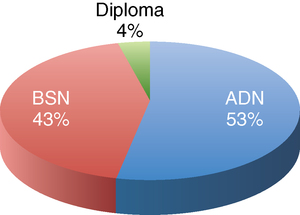

After studying this chapter, students will be able to: • Trace the development of basic and graduate education in nursing. • Discuss the influence of early nursing studies on nursing education. • Describe traditional and alternative ways of becoming a registered nurse. • Discuss program options for registered nurses and students with non-nursing bachelor’s degrees. • Differentiate between licensed practical/vocational nurses and registered nurses. • Differentiate between associate degree and bachelor’s degree education. • Explain the difference between licensure and certification. • Define “accreditation” and analyze its influence on the quality and effectiveness of nursing education programs. • Discuss recommendations of the Institute of Medicine and major nursing organizations regarding transforming nursing education. • List Quality and Safety Education in Nursing competencies. Chapter opening photo from Photos.com. Leaders in nursing education today seek to transform the nursing workforce in a way that honors nursing’s social contract with the public, recognizing that education of nurses plays a critical role in their ability to achieve optimal outcomes for their patients, and to practice safely. In 2009, Patricia Benner, PhD, RN, FAAN and her team at the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching published a study, Educating Nurses: A Call for Radical Transformation. In addition to calling for a bachelor of science in nursing (BSN) as the entry level for registered nurse (RN) practice, this team recommended that all RNs be required to earn a master of science in nursing (MSN) within 10 years of licensure. They found that nurses are undereducated to meet the demands of today’s practice. Their recommendations represent a radical change in basic nursing education, but they make a compelling argument for extending the education of nurses entering the workforce (Benner, Sutphen, Leonard et al., 2009). 1. Nurses must practice to the fullest extent of their education and training. 2. Nurses should attain higher education levels through a system of improved education with seamless progression across degrees. 3. As health care in the United States is being transformed, nurses should be full partners with other health care professionals in this effort. 4. Improved data collection and information infrastructure can result in more effective workforce planning and policy development. In addition to the Carnegie and IOM reports, two other important sources called for advancement in nursing education between 2009 and 2010. Linda Aiken, PhD, RN, FAAN and her colleagues called for increased federal support for the preparation of nurses at the BSN level and higher (Aiken, Cheung, Olds, 2009). They suggested policy changes to address the growing need for nursing faculty and in the preparation of advanced practice nurses (APNs) to serve in primary care. In 2010, the Tri-Council for Nursing (an alliance of the American Nurses Association [ANA], American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], American Organization of Nurse Executives, and National League of Nursing [NLN]) released a policy statement that included this language (Tri-Council for Nursing, 2010): Florence Nightingale (Figure 7-1) is credited with founding modern nursing and creating the first educational system for nurses. After hospitals came into existence in Western Europe, and before the influence of Florence Nightingale, nurses had no formal preparation in giving care, because there were no organized programs to educate nurses until the late 1800s. Before this, nursing care was administered by either the patient’s relatives, individuals affiliated with religious or military nursing orders, or self-trained persons who were often held in low regard by society. 1. The nurse should be trained in an educational institution supported by public funds and associated with a medical school. 2. The nursing school should be affiliated with a teaching hospital but also should be independent of it. 3. The curriculum should include both theory and practical experience. 4. Professional nurses should be in charge of administration and instruction and should be paid for their instruction. 5. Students should be carefully selected and should reside in “nurses’ houses” that form discipline and character. (Nightingale envisioned nursing as a profession only for women.) 6. Students should be required to attend lectures, take quizzes, write papers, and keep diaries. Student records should be maintained (Notter and Spalding, 1976). The first training schools for nurses in the United States were established in 1872. Located at Bellevue Hospital in New York; the New England Hospital for Women and Children in New Haven, Connecticut; and Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, the course of study was 1 year in length. These schools became known as the “famous trio” of nursing schools. In October 1873, Melinda Anne “Linda” Richards became the first “trained nurse” educated in the United States. By 1879, there were 11 U.S. nursing training schools. Other schools rapidly developed, and by 1900 there were 432 hospital-owned and hospital-operated programs in the United States (Donahue, 1985). These early training programs differed in length from 6 months to 2 years, and each school set its own standards and requirements. On graduation from these programs, students were awarded a diploma. The term “diploma program” was, and still is, used to identify hospital-based nursing education programs. The primary reason for the schools’ existence was to staff the hospitals that operated them. The education of student nurses was not always the primary concern. Mary Adelaide Nutting came to Teachers College in 1907 as the first nursing professor the world had ever known. Under her direction, the department progressed and became a pioneer in nursing education. The school became known as the “Mother House” of collegiate education because it fostered the initial movements toward undergraduate and graduate degrees for nurses (Donahue, 1985). In 1912, Nutting conducted a nationwide investigation of nursing education, The Educational Status of Nursing, that focused on the living conditions of students, the material being taught, and the teaching methods being used (Christy, 1969). Another major study of nursing education was published in 1923. Titled The Study of Nursing and Nursing Education in the United States and referred to as the Goldmark Report, the study focused on the clinical learning experiences of students, hospital control of the schools, the desirability of establishing university schools of nursing, the lack of funds specifically for nursing education, and the lack of prepared teachers (Kalisch and Kalisch, 1995). The year 1924 marked another first in nursing education when the Yale School of Nursing was opened as the first nursing school to be established as a separate university department with an independent budget and its own dean, Annie W. Goodrich. The school demonstrated its effectiveness so well that in 1929 the Rockefeller Foundation ensured the permanency of the school by awarding it an endowment of $1 million (Kalisch and Kalisch, 1995). In 1934, a study entitled Nursing Schools Today and Tomorrow reported the number of schools in existence, gave detailed descriptions of the schools, described their curricula, and made recommendations for professional collegiate education (National League of Nursing Education, 1934). In 1937, A Curriculum Guide for Schools of Nursing was published, outlining a 3-year curriculum and influencing the structure of diploma schools for decades after its publication (National League of Nursing Education, 1937). 1. Nursing education programs should be established within the system of higher education. 2. Nurses should be highly educated. 3. Students should not be used to staff hospitals. 4. Standards should be established for nursing practice. 5. All students should meet certain minimum qualifications on graduation. These studies set the stage for the development of the educational programs that exist today. Today, preparation for a career as an RN usually begins in one of three ways: in a hospital-based diploma program, a BSN program, or an associate degree in nursing (ADN) program. These basic programs vary in the courses offered, length of study, and cost. After the completion of a basic program for RNs, graduates are eligible to take the National Council Licensure Examination for Registered Nurses (NCLEX-RN®). On successful completion of the licensing examination, graduates may legally practice as RNs and use the RN credential. Figure 7-2 shows the percentage of enrollments in RN programs by type in 2008. Seven other BSN programs were established by 1919 (Conley, 1973). Most of the early BSN programs were 5 years in duration. This structure provided for 3 years of nursing education and 2 years of liberal arts. The growth in the numbers of these programs was slow both because of the reluctance of universities to accept nursing as an academic discipline and because of the power of the hospital-based diploma programs. The theoretical, scientific orientation of the BSN program was in sharp contrast to the “hands-on” skill and service orientation that was the hallmark of hospital-based diploma education. National studies of nursing and nursing education stated and restated the need for nursing education and practice to be based on knowledge from the sciences and humanities. Chief among these studies was Esther Lucille Brown’s report Nursing for the Future, more commonly known as the Brown Report. Published in 1948, the Brown Report recommended that basic schools of nursing be placed in universities and colleges, with effort made to recruit men and minorities into nursing education programs (Brown, 1948). This report, sponsored by the Carnegie Foundation, was widely reviewed, discussed, and debated. 1. Education for all those who are licensed to practice nursing should take place in institutions of higher learning. 2. Minimum preparation for beginning professional nursing practice should be the baccalaureate degree in nursing. 3. Minimum preparation for beginning professional nursing practice should be the baccalaureate degree in nursing. 4. Education for assistants in the health service occupations should consist of short, intensive preservice programs in vocational education institutions rather than on-the-job training programs. 1. By 1985 the minimum preparation for entry into professional nursing practice should be the BSN. 2. Two levels of nursing practice should be identified (professional and technical) and a mechanism to devise competencies for the two categories established by 1980. 3. There should be increased accessibility to high-quality career mobility programs that use flexible approaches for individuals seeking academic degrees in nursing. In the mid-1980s, the National Commission on Nursing suggested that the major block to the advancement of nursing was the ongoing conflict within the profession about educational preparation for nurses. The Commission recommended establishing a clear system of nursing education, including pathways for educational mobility and development of additional graduate education programs (De Back, 1991). In 1996, the AACN board approved a position statement, The Baccalaureate Degree in Nursing as Minimal Preparation for Professional Practice. This document supports, among other things, articulated programs, which enable associate degree nurses to attain the BSN (AACN, 1996). This document was updated in 2000. It can be found online (www.aacn.nche.edu/Publications/positions/baccmin.htm). Basic BSN programs combine nursing courses with general education courses in a 4-year curriculum in a senior college or university. Students may be admitted to the nursing program as entering freshmen or after completing certain liberal arts and science courses. Students meet the same admission requirements to the university as other students and often must meet even more stringent requirements to be admitted to the nursing major. Courses in the nursing major focus on nursing science, communication, decision making, leadership, and care to persons of all ages in a wide variety of settings (Figure 7-3). Faculty qualifications in BSN programs are usually higher than in other basic nursing programs. A minimum of a master’s degree for clinical faculty and a doctorate in nursing or a related field is required for permanent, tenure-track faculty. The requirement of a doctorate ensures that nursing faculty members are able to meet the teaching, research, and service requirements expected of all faculty in universities. Nursing faculty work leads to many interesting possibilities for collaboration in very distant countries. Box 7-1 tells of the experiences of Wendy Woith, PhD, RN in doing her research in Russia with health care workers and tuberculosis, after a lifetime of interest in that country (Figure 7-4).

The education of nurses: On the leading edge of transformation

![]() To enhance your understanding of this chapter, try the Student Exercises on the Evolve site at http://evolve. elsevier.com/Black/professional.

To enhance your understanding of this chapter, try the Student Exercises on the Evolve site at http://evolve. elsevier.com/Black/professional.

Development of nursing education in the united states

Early studies of the quality of nursing education

Educational pathways to becoming a registered nurse

Baccalaureate programs

Influences on the growth of baccalaureate education

Baccalaureate programs today

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The education of nurses: On the leading edge of transformation

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access