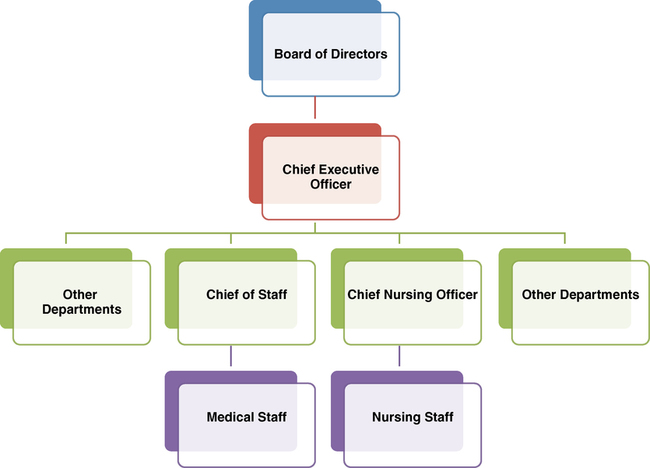

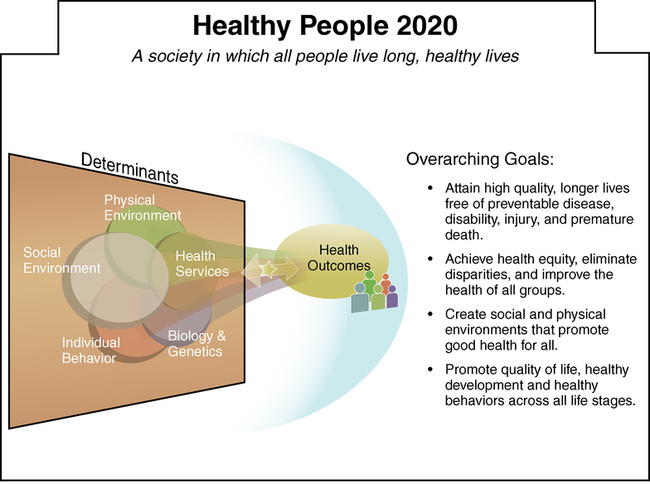

After studying this chapter, students will be able to: • Describe the four basic categories of services provided by the health care delivery system. • Describe the shared governance model and explain its use in nursing. • Describe the relationship between cost-containment and quality management initiatives. • Relate two major mechanisms used to maintain quality in health care agencies. • Explain how disparities in health care disproportionately impact minority and poor populations. • Identify the key members of the interdisciplinary health care team and explain what each contributes. • Discuss seven primary roles of nurses in the health care delivery system. • Differentiate among five nursing care delivery systems in use today. • Explain the economic principles of supply and demand, free-market economies, and price sensitivity and discuss their relevance to health care costs. • Explain cost-containment efforts and their effect on nursing practice. • Describe current methods of payment for health care. • Discuss the role of nurses in managing costs. • Discuss universal health care as an outcome of health care reform. To enhance your understanding of this chapter, try the Student Exercises on the Evolve site at http://evolve. elsevier.com/Black/professional. Chapter opening photo from Photos.com. The U.S. federal government has yet to devise a definitive national health policy. A first step, however, has been taken. In 1979, the federal government initiated the Healthy People program, a science-based program that sets forth, every 10 years, national objectives focusing on health promotion and disease prevention. Every decade Healthy People sets and monitors national health objectives, building on lessons learned in the previous decade. Input is sought from both experts and the general public through a collaborative process. The Healthy People campaign was instituted in the late 1990s to establish health benchmarks and monitor progress toward these benchmarks. The intention was to encourage collaborations across communities and sectors; empower persons to make informed health decisions; and measure the impact of prevention activities (www.healthypeople.gov). The overarching goals for Healthy People 2020 are shown in Figure 14-1. Prevention services differ from health promotion services in that they address health problems after risk factors are identified, whereas health promotion services seek to prevent development of risk factors. For example, a health promotion program might teach the detrimental effects of alcohol and drugs on health to prevent individuals from using alcohol and drugs. Illness prevention services are used when the patient has been abusing alcohol or drugs and is at risk for developing conditions related to using these substances. The boundaries between health promotion and maintenance, early detection, and illness prevention are often blurred. Box 14-1 gives examples of activities in these three areas. Boards now carry significant responsibility for the mission of the organization, the quality of services provided, and the financial stability of the organization. Boards are not involved in the day-to-day running of the agency, but they are legally responsible for establishing policies governing operations and for ensuring that the policies are executed. They delegate responsibility for running the agency to the chief executive officer (CEO). Boards of directors may or may not be paid for their services. Box 14-2 is a list of the primary responsibilities of the board of directors of a not-for-profit health care provider (e.g., hospital; hospice). The concept of shared governance is founded on the philosophy that employees have both a right and a responsibility to govern their own work and time within a financially secure, patient-centered system. Shared governance promotes decentralization and participation at all levels of nursing. In shared governance, the role of the clinical nursing staff is to be responsible for the professional practice of their nursing unit by adhering to standards and benchmarks of quality care (Davis, 2008). The role of the nurse manager and other nurse leaders is to set expectations, facilitate, coordinate, support, and create partnerships with the staff in achieving the identified goals. An example of shared governance is self-scheduling, in which staff members determine their own schedules based on established guidelines for staffing the unit set forth by the manager. The shared governance model promotes improved patient outcomes and enhanced nurse job satisfaction brought about by increased autonomy. Health care organizations are complex entities. The way they are organized may vary, but each has an organizational chart that shows its unique structure and explains lines of authority. When considering employment in a health care organization, you can learn a great deal by examining its organizational chart to see how nursing is governed and how it relates to senior management and the board of directors. Figure 14-2 shows an example of a basic health care organizational chart. Health care organizations such as hospitals, home health agencies, and long-term care facilities seek accreditation through one of two accrediting bodies approved by the CMS. They are The Joint Commission, a not-for-profit organization that serves as the nation’s predominant standard-setting and accrediting body in health care (The Joint Commission, 2012), and the Healthcare Facilities Accreditation Program, authorized by the CMS. The goal of accreditation is to improve patient outcomes. Accreditation is important and requires that a number of standards be met in every department. Considerable resources of time and money are spent making sure accreditation criteria, set by these external accrediting bodies, are met. Health care disparities are differences in access to and the quality of health care provided to different populations. Ethnic or racial disparities receive much attention among those examining health care delivery; however, differences also have been found to exist between the treatment and treatment outcomes of men and women, as well as younger and older people. The causes of disparities may be due to race, ethnicity, gender, age, income, education, disability, sexual orientation, and place of residence (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2007). Most likely a combination of these and possibly other factors leads to disparities, which have been difficult to reduce despite increasing attention to their significant negative effect on large segments of the population. Provider bias has been mentioned as a possible contributing factor to health care disparities. For example, a study examining treatment of adults with soft-tissue cancers of an arm or a leg “showed that blacks had the lowest rates of limb-preserving surgeries and the highest rates of amputations in comparison with white, Hispanic, and Asian patients” (Voelker, 2008). This study found that black patients also had the lowest rates of radiation therapy used in conjunction with surgery compared with other groups. This chapter’s Cultural Considerations Challenge contains more information about health care disparities. If this is a topic you wish to learn more about, you will find a continuing education module, “Disparities in Health Care: Focusing Efforts to Eliminate Unequal Burdens” by D. Baldwin in the American Nurses Association (ANA) online journal Online Journal of Issues in Nursing (OJIN). Follow links at the ANA website (www.nursingworld.org).

Health care in the United States

Today’s health care system

Major categories of health care services

Illness prevention

Classifications of health care agencies

Organizational structures within health care agencies

Organizational structure

Board of directors.

Nursing organization governance.

Maintaining quality in health care agencies

Accreditation of health care agencies

A continuing challenge: Health care disparities