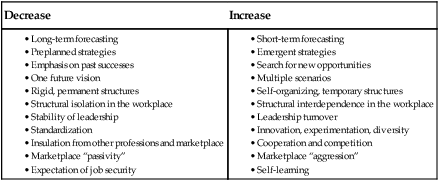

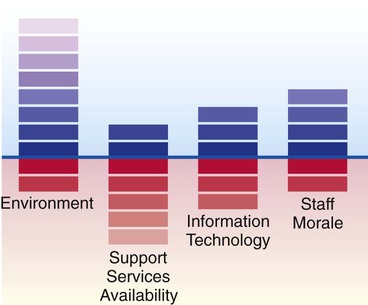

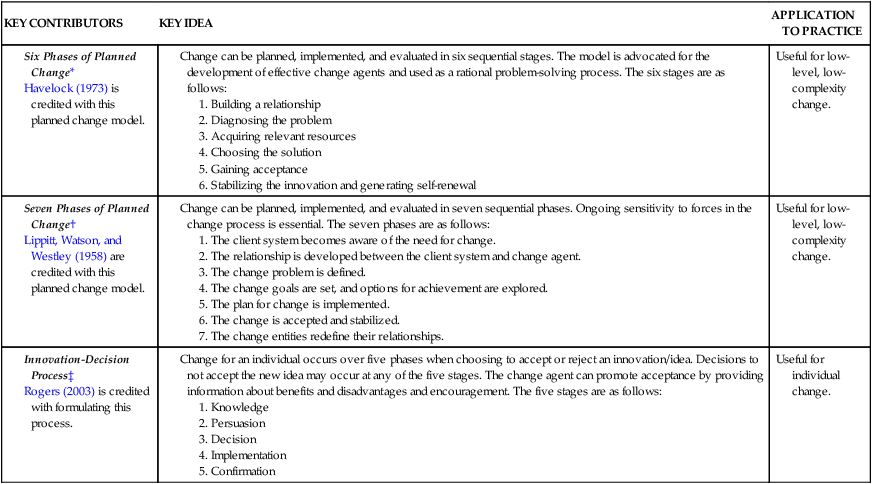

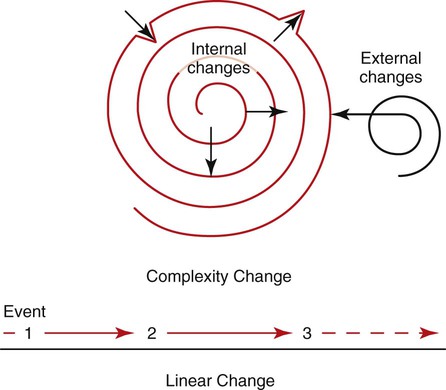

• Analyze the general characteristics of change in open-system organizations. • Relate the models of planned change to the process of low-level change. • Evaluate nonlinear theories for managing high-level change. • Evaluate the use of select functions, principles, and strategies for initiating and managing change. The healthcare manager must factor in time, information, decision making, and planning (Begun & White, 1995). In an increasingly uncertain world, managers and leaders in our profession are challenged to be skilled in using change theory, serving as change agents, and supporting staff during times of change. According to the American Organization of Nurse Executives (AONE) (2005), managers and leaders need to do the following: • Use change theory to plan for the implementation of organizational change • Serve as change agent, assisting others in understanding the importance, necessity, and processes of change • Support staff during times of difficult transitions • Recognize one’s own reaction to change, and strive to remain open to new ideas and approaches Nursing entities, as open systems, need to begin viewing their work in less bureaucratic, inflexible ways and open themselves up to responding with flexibility and creativity to today’s dynamic environment (Begun & White, 1995). Using planned linear change was useful when cycles in society and health care were somewhat stable (low-complexity change). The highly complex, accelerated, and unpredictable change situations of today still require planning, but on a constantly changing basis. Nurses are key players in healthcare delivery. They are partners with multiple care providers and pivotal players in open-systems organizations. In their classic work, Begun and White (1995) said that it was important for nursing to consider its dominant logic as a source of structural inertia. Using chaos theory components, they suggested that nursing in certain organizations is too “stuck” and thus too unresponsive and unable to adapt to the influences of rapid change. Today, nursing organizations that achieve designation by the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC) with Magnet™ status are typically ones that are flexible, adaptive, and innovative. They can lead change by putting into place programs that capitalize on rapid change and thus improve patient safety and nurses’ work environment and achieve quality outcomes. One way the nurse leader can alter the dominant logic is shown in Box 17-1. Using this methodology, the manager becomes adept at addressing an emergent approach to change that takes place over a long period rather than sporadic and episodic reactions to change (Shanley, 2007). Scenario planning (i.e., raising multiple “what if” questions with many possible alternative answers) is an example of the needed flexibility and creativity urgently needed in nursing today. There are two approaches commonly referred to in the literature on change: linear and nonlinear. Planned change models, or linear approaches, can guide directional, incremental, low-level, less-complex changes. Examples are reorganizing the storage of unit supplies and publishing staff development courses for nurses. Changes that represent higher-level thinking, on the other hand, are characteristically more fluid and complex because of the number of interactions and the activities of multiple players and their influences across the organization. Usually, nonlinear change approaches are found in complexity/chaos and learning organization theories. They offer helpful approaches for understanding dynamic, open-system healthcare organizations and for guiding change agents in managing accelerated, increasingly uncertain change environments (Menix, 2000, 2001). Change agents in planned changes focus on specific goals and the incremental steps needed to attain those goals. Change agents in nonlinear, complex changes serve as monitors of the environment, negotiators of influences on a change, and precise forecasters of possible scenarios and their anticipated outcomes. Most planned change models—linear models—advocate that change can occur in a sequential and directional fashion when guided by effective change agents. The early planned change models, such as those of Lewin (1947); Lippitt, Watson, and Westley (1958); and Havelock (1973), explain the nature of change processes and offer systematic problem-solving methods designed to achieve change. The use of planned change can be useful for low-level change in more stable environments. Flexibility in implementing the plan and moderating the situational factors, as is advocated by nonlinear approaches, can then be introduced to improve the overall outcomes. However, to make change happen, the group has to progress through it. The group cannot let only a few make the changes. Sticking with and advancing the change is daily work that requires the undivided focus of all team members. Lewin (1947) suggested that an analysis of change situations, which he called force field analysis, includes early and ongoing assessment of barriers and facilitators. Barriers in change situations are factors that can hinder the change process; facilitators are factors that can expedite the process. These elements may originate with people, technology, structure, or values. For change to be effective, the force of facilitators must exceed the force of barriers; thus the work of change agents is to reduce the barriers in the situation and support or enhance the facilitators. Figure 17-1 illustrates an example of how to diagram forces so that a visual portrays the strengths and barriers of any change. In this case, the strengths outweigh the barriers. Lewin (1947) describes change as having three stages: Experiencing the change or solution leads to incorporation of what is new or different into work and interpersonal processes (Lewin, 1947). Deciding to begin to use the change or being unexpectedly thrust into the change can result in potential integration of the new way of thinking or doing. Refreezing occurs when the participants in the change situation accept and use the new attitude or behavior (Lewin, 1947). Acceptance is assumed once most staff members integrate the change into their work processes. Surveys, structured or unstructured observations, or other data-collection methods can be conducted at various points after the implementation of a specific change to measure the effectiveness of the new approach. Analysis of these data can help evaluate the degree of implementation and identify additional alterations needed to ensure an effective change outcome. Although Havelock’s (1973) six-stage model for planning change had particular application to educational entities (see the Theory Box below), it shows similarities in the elements of the directional phases recommended by other planned-change models. Two adjuncts to Havelock’s model advocate development of the effective change agent and use of his model as a rational problem-solving process. The rational problem-solving process is “how change agents can organize their work so that successful innovation will take place” (p. 3). Lippitt, Watson, and Westley’s (1958) model suggests seven sequential phases to use to plan change (see the Theory Box below). Inherent in this model is the change agent’s appraisal of the “change and resistance forces which are present in the client system at the beginning of the change process as well as others which may be revealed as the process advances. Being continuously sensitive to the constellation of change forces and resistance forces is one of the most creative parts of the change agent’s job” (p. 92). The innovation-decision process (Rogers, 2003) describes the choice of an individual, over time, to accept or reject a new idea for use in practice (see the Theory Box on p. 328). According to Rogers’ work, the individual’s decision-making actions pass through five sequential stages. The decision to not accept the new idea may occur at any stage. However, the change agent can facilitate movement by others through these stages by encouraging the use of the idea and providing information about its benefits and disadvantages. Organizations can no longer rely on rules, policies, and hierarchies to enforce change and achieve outcomes in rigid and inflexible ways. According to chaos theory, the rapidly changing nature of human and world factors underscores how an emphasis on rules and policies is shortsighted, wastes time, and fails to accomplish goals in the long run. Organizations are open systems operating in complex, fast-changing environments. The term open by itself suggests that such systems (organizations/services) are affected by and simultaneously affect their environment. These systems are similar to semipermeable membranes, allowing some exchanges between the internal and external environments. Non–human-induced responses are characterized by random-appearing yet self-organizing patterns. Constant adaptation and the mere anticipation of change force organizations to remain relevant in their environment. The cycle of change dictates that, typically, organizations experience periods of stability interrupted by periods of intense transformation, thus demonstrating “spurts” of change rather than continuously steady, incremental change. Although not immediately predictable in the long run, small changes in the internal or external environment can certainly result in significant consequences to organizational work processes and outcomes. Chaos theory further explains that the conditions present in a particular organizational change will not occur again in the same form (Vicenzi, White, & Begun, 1997). Figure 17-2 illustrates the contrasting patterns. Learning organizations are organizations that place emphasis on flexibility and responsiveness (Senge, 1990). Specifically, complex organizations that are responsive to internal and external influences are trying to survive in an unpredictable healthcare environment. They can best respond and adapt when members of the organization complete their work with others using a learning approach. Enactment of Senge’s five disciplines is essential to achieving learning organization status. Disciplines refers to the grouping that comprises critical and interrelated elements; this grouping can function effectively only when all elements are present, linked, and interacting. For example, an automobile with a working engine and other essential operational features but no tires could not be driven as designed. Without the knowledge of the interrelatedness of the automobile’s operational features, one might not be able to take the right action to use this form of transportation. Senge’s (1990) five disciplines of learning organizations are the following: Dialog (two-way discussion) promotes the individual, group, and organizational learning process. Systems thinking refers to the need for the organization to view the world as a set of multiple visible and invisible parts that interact constantly. When the organization values and facilitates development of the deeper aspirations of its members in addition to professional proficiency, it successfully matches organizational learning and personal growth or personal mastery. Each individual and each organization base their activities on a set of assumptions, beliefs, and mental pictures about the way the world should work. When these invisible mental models are uncovered and consciously evaluated, it is possible to begin to determine, in a “learningful” (Senge, 1990, p. 9) way, their influence on work accomplishment. Building shared vision occurs when leaders involve all members in moving personal visions of the future into a consolidated yet ongoing vision common to members and leaders. Team learning refers to the need for a cohesive group to learn together to benefit from the abilities of each member, thereby enhancing the overall outcomes of the team’s efforts. Organizations value employees who can learn continuously, interact and communicate effectively as team members, and seek to meet their potential as team members.

Leading Change

Context of the Change Environment

Planned Change Using Linear Approaches

Nonlinear Change: Chaos and Learning Organization Theories

Chaos Theory

Learning Organization Theory

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access