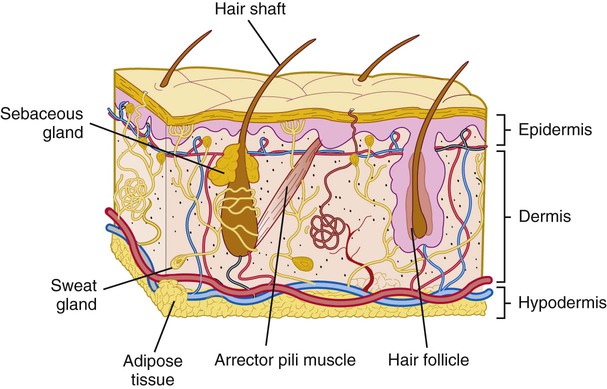

1. Describe the structure of the two layers of the skin. 2. State three names for the layer of tissue that anchors the skin to underlying organs, and describe the structure of this layer. 3. List three factors that influence skin color. 4. Describe the structure of hair and nails and their relationship to the skin. 5. Discuss the characteristics and functions of the various glands associated with the skin. 6. List and describe four functions of the integumentary system. 7. Describe ways in which the aging of an individual affects the integumentary system. The structure of the skin is illustrated in Figure 6-1. The outer layer of the skin is the epidermis. This layer consists of stratified squamous epithelium (see Figure 6-1). There are no blood vessels present in the epidermis, and the cells receive their nutrients by diffusion from vessels in the underlying tissue. The bottom row of cells in the epidermis is called the stratum basale. It consists of actively dividing (mitotic) columnar cells and melanocytes. This is the layer next to the basement membrane and closest to the blood supply. As older cells are pushed upward toward the surface by the growing cells next to the basement membrane, they receive fewer nutrients. They also undergo a process called keratinization (ker-ah-tin-ih-ZAY-shun). During keratinization, a protein called keratin is deposited in the cell. This causes the chemical composition of the cell to change, and the cell changes shape. By the time the cells reach the surface, they are flat or squamous. They are also dead from lack of nutrients and are sloughed off. They are replaced by other cells that are pushed upward from the stratum basale. About one fourth of the cells in the stratum basale are melanocytes (meh-LAN-oh-sytes). Melanocytes are specialized epithelial cells that produce a dark pigment called melanin (MEL-ah-nin), which is primarily responsible for skin color. The dermis, or stratum corium (KOR-ee-um), is dense connective tissue that is deeper and usually thicker than the epidermis (see Figure 6-1). Hair, nails, and certain glands (although derived from the stratum basale of the epidermis) are embedded in the dermis. The dermis contains both collagenous and elastic fibers to give it strength and elasticity. If the skin is overstretched, the dermis may be damaged, leaving white scars called striae (STRY-ee), commonly called “stretch marks.” Fibers also form a framework for the numerous blood vessels and nerves that are present in the dermis but generally absent in the epidermis. Many of the nerves in the dermis have specialized endings called sensory receptors that detect changes in the environment, such as heat, cold, pain, pressure, and touch. Because there are no nerves in the epidermis, these receptors are the body’s contact with the environment.

Integumentary System

Introduction to the Integumentary System

Structure of the Skin

Epidermis

Dermis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Integumentary System

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access