Home Visit

Opening the Doors for Family Health

Claudia M. Smith

Focus Questions

Why are home visits conducted?

What are the advantages and disadvantages of home visits?

How can a nurse’s family focus be maximized during a typical home visit?

What promotes safety for community/public health nurses?

What happens during a typical home visit?

Key Terms

Agreement

Collaboration

Consultation

Empathy

Family focus

Genuineness

Home visit

Positive regard

Presence

Referral

Nurses who work in all specialties and with all age groups can practice with a family focus, that is, thinking of the health of each family member and of the entire family per se and considering the effects of the interrelatedness of the family members on health. Because being family focused is a philosophy, it can be practiced in any setting. However, a family’s residence provides a special place for family-focused care.

Community/public health nurses have historically sought to promote the well-being of families in the home setting (Zerwekh, 1990). Community/public health nurses seek to promote health; prevent specific illnesses, injuries, and premature death; and reduce human suffering. Through home visits, community/ public health nurses provide opportunities for families to become aware of potential health problems, to receive anticipatory education, and to learn to mobilize resources for health promotion and primary prevention (Kristjanson & Chalmers, 1991; Raatikainen, 1991). In clients’ homes, care can be personalized to a family’s coping strategies, problem-solving skills, and environmental resources (see Chapter 13).

During home visits, community/public health nurses can uncover threats to health that are not evident when family members visit a physician’s office, health clinic, or emergency department (Olds et al., 1995; Zerwekh, 1991). For example, during a visit in the home of a young mother, a nursing student observed a toddler playing with a paper cup full of tacks and putting them in his mouth. The student used the opportunity to discuss safety with the mother and persuaded her to keep the tacks on a high shelf. The quality of the home environment predicts the cognitive and social development of an infant (Engelke & Engelke, 1992). Community/public health nurses successfully assist parents in improving relations with their children and in providing safe, stimulating physical environments.

All levels of prevention can be addressed during home visits. Research has demonstrated that home visits by nurses during the prenatal and infancy periods prevent developmental and health problems (Kitzman et al., 2000; Norr et al., 2003; Olds et al., 1986). Olds and colleagues demonstrated that families who received visits had fewer instances of child abuse and neglect, emergency department visits, accidents, and poisonings during the child’s first 2 years of life. These results were true for families of all socioeconomic levels but greater for low-income families. The health outcomes for families who received home visits were better than those of families that received care only in clinics or from private physicians. Furthermore, the favorable results were still apparent 15 years after the birth of the first child (Olds et al., 1997), and the home visits reduced subsequent pregnancies (Kitzman et al., 1997; Olds et al., 1997). The U.S. Advisory Board on Abuse and Neglect advocates such home-visiting programs as a means to prevent child abuse and neglect (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1990). Other research shows that home visits by nurses can reduce the incidence of drug-resistant tuberculosis and decrease preventable deaths among infected individuals (Lewis & Chaisson, 1993). This goal is achieved through directly observing medication therapy in the individual’s home, workplace, or school on a daily basis or several times a week (see Chapter 8).

Several factors have converged to expand opportunities for nursing care to adults and children with illnesses and disabilities in their homes. The American population has aged, chronic diseases are now the major illnesses among older persons, and attempts are being made to limit the rising hospital costs. As the average length of stay in hospitals has decreased since the early 1980s, families have had to care for more adults and children with acute illnesses in their homes. This increased demand for home health care has resulted in more agencies and nurses providing home care to the ill and teaching family members to perform the care (see Chapter 31).

The degree to which families cope with a member with a chronic illness or disability significantly affects both the individual’s health status and the quality of life for the entire family (Burns & Gianutsos, 1987; Harris, 1995; Whyte, 1992). Family members may be called on to support an individual family member’s adjustment to a chronic illness as well as take on tasks and roles that the ill member previously performed. This adjustment occurs over time and often takes place in the home. Community/public health nurses can assist families in making these adjustments.

Since the late 1960s, deinstitutionalization of mentally ill clients has shifted them from inpatient psychiatric settings to their own homes, group homes, correctional facilities, and the streets (see Chapter 33). Nurses in the fields of community mental health and psychiatry began to include the relatives and surrogate family members in providing critical support to enable the person with a psychiatric diagnosis to live at home (Mohit, 1996; Stolee et al., 1996).

The hospice movement also recognizes the importance of a family focus during the process of a family member’s dying (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2007a). Care at home or in a homelike setting is cost effective under many circumstances. As the prevalence of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) increases and the number of older adults continues to increase, providing care in a cost-effective manner is both an ethical and an economic necessity.

Nurses in any specialty can practice with a family focus. However, the specific goals and time constraints in each health care service setting affect the degree to which a family focus can be used. A home visit is one type of nurse–client encounter that facilitates a family focus. Home visiting does not guarantee a family focus. Rather, the setting itself and the structure of the encounter provide an opportunity for the nurse to practice with a family focus.

Nurses who graduate from a baccalaureate nursing program are expected to have educational experiences that prepare them for beginning practice in community/public health nursing. Family-focused care is an essential element of community/public health nursing. One of the ways to improve the health of populations and communities is to improve the health of families (ANA, 2007b).

Home visits may be made to any residence: apartments for older adults, group homes, boarding homes, dormitories, domiciliary care facilities, and shelters for the homeless, among others. In these residences, the family may not be related by blood, but, rather, they may be significant others: neighbors, friends, acquaintances, or paid caregivers.

Nurses who are educated at the baccalaureate level are one of a few professional and service workers who are formally taught about making home visits. Some social work students, especially those interested in the fields of home health and protective services, also receive similar education. The American Red Cross and the National Home Caring Council have developed training programs for homemakers and home health aides; not all aides have received such extensive training, however. Agricultural and home economic extension workers in the United States and abroad also may make home visits (Murray, 1968; World Health Organization, 1987).

Home visit

Definition

A home visit is a purposeful interaction in a home (or residence) directed at promoting and maintaining the health of individuals and the family (or significant others). The service may include supporting a family during a member’s death. Just as a client’s visit to a clinic or outpatient service can be viewed as an encounter between health care professionals and the client, so can a home visit. A major distinction of a home visit is that the health care professional goes to the client rather than the client coming to the health care professional.

Purpose

Almost any health care service can be accomplished on a home visit. An assumption is that—except in an emergency—the client or family is sufficiently healthy to remain in the community and to manage health care after the nurse leaves the home.

The foci of community/public health nursing practice in the home can be categorized under five basic goals:

The five basic goals of community/public health nursing practice with families can be linked to categories of family problems (Table 11-1). A pilot study to identify problems common in community/public health nursing practice settings revealed that problems clustered into four categories: (1) lifestyle and living resources, (2) current health status and deviations, (3) patterns and knowledge of health maintenance, and (4) family dynamics and structure (Simmons, 1980). Home visits are one means by which community/public health nurses can address these problems and achieve goals for family health.

Table 11-1

Family Health-Related Problems and Goals

| Problem* | Goal |

| Lifestyle and resources | Promote support systems and use of health-related resources |

| Health status deviations | Promote adequate, effective family care of a member with an illness or disability |

| Patterns and knowledge of health maintenance | Encourage growth and development of family members, health promotion, and illness prevention Promote a healthful environment |

| Family dynamics and structure | Strengthen family functioning and relatedness |

*Problems from Simmons, D. (1980). A classification scheme for client problems in community health nursing (DHHS Pub No. HRA 8016). Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Advantages of home visits by nurses are numerous. Most of the disadvantages relate to expense and concerns about unpredictable environments (Box 11-1).

Nurse–family relationships

How nurses are assigned to make home visits is both a philosophical and a management issue. Some community/public health nurses are assigned by geographical area or district. The size of the geographical area for home visits varies with the population density. In a densely populated urban area, a nurse might visit in one neighborhood; in a less densely populated area, the nurse might be assigned to visit in an entire county. With geographical assignments, the nurse has the potential to work with the entire population in a district and to handle a broad range of health concerns; the nurse can also become well acquainted with the community’s health and social resources. The potential for a family-focused approach is strengthened because the nurse’s concerns consist of all health issues identified with a specific family or group of families. The nurse remains a clinical generalist, working with people of all ages.

Other community/public health nurses are assigned to work with a population aggregate in one or more geopolitical communities. For example, a nurse may work for a categorical program that addresses family planning or adolescent pregnancy, in which case the nurse would visit only families to which the category applies. This type of assignment allows a nurse to work predominantly with a specific interest area (e.g., family planning and pregnancy) or with a specific aggregate (e.g., families with fertile women).

Principles of Nurse–Client Relationship with Family

Regardless of whether the community/public health nurse is assigned to work with an aggregate or the entire population, several principles strengthen the clarity of purpose:

• By definition, the nurse focuses on the family.

• The health focus can be on the entire spectrum of health needs and all three levels of prevention.

• The family retains autonomy in health-related decisions.

Family Focus

To relate to the family, the community/public health nurse does not have to meet all members of the household personally, although varying the times of visits might allow the nurse to meet family members usually at work or school. Relating to the family requires that the nurse be concerned about the health of each member and about each person’s contribution to the functioning of the family. One family member may be the primary informant; in such instances, the nurse should realize that the information received is being filtered by the person’s perceptions.

The community/public health nurse should take the time to introduce herself or himself to each person present and address each person by name. Building trust is an essential foundation for a continued relationship (Heaman et al., 2007; McNaughton, 2000; Zerwekh, 1992). The nurse should use the clients’ surnames unless they introduce themselves in another way or give permission for the nurse to be less formal. Interacting with as many family members as possible, identifying the family member most responsible for health issues, and acknowledging the family member with the most authority are important. The nurse should ask for an introduction to pets and ask for permission before picking up infants and children unless it is granted nonverbally.

All Levels of Prevention

Through assessment, the community/public health nurse attempts to identify what actual and potential problems or concerns exist with each individual and, thematically, within the family (see Chapter 13). Issues of health promotion (diet) and specific protection (immunization) may exist, as may undiagnosed medical problems for which referral is necessary for further diagnosis and treatment. Home visits also can be effective in stimulating family members to seek appropriate services such as prenatal care (Bradley & Martin, 1994) and immunizations (Norr et al., 2003). Actual family problems in coping with illness or disability may require direct intervention. Preventing sequelae and maximizing potential may be appropriate for families with a chronically ill member. Health-related problems may appear predominantly in one family member or among several members. A thematic family problem might be related to nutrition. For example, a mother may be anemic, a preschooler may be obese, and a father may not follow a low-fat diet for hypertension.

Family Autonomy

A few circumstances exist in our society in which the health of the community, or public, is considered to have priority over the right of individual persons or families to do as they wish. In most states, statutes (laws) provide that health care workers, including community/public health nurses, have a right and an obligation to intervene in cases of family abuse and neglect, potential suicide or homicide, and existence of communicable diseases that pose a threat of infection to others. Except for these three basic categories, the family retains the ultimate authority for health-related decisions and actions.

In the home setting, family members participate more in their own care. Nursing care in the home is intermittent, not 24 hours a day. When the visit ends, the family takes responsibility for their own health, albeit with varying degrees of interest, commitment, knowledge, and skill. This role is often difficult for beginning community/public health nurses to accept; learning to distinguish the family’s responsibilities from the nurse’s responsibilities involves experience and consideration of laws and ethics. Except in crises, taking over for the family in areas in which they have demonstrated capability is usually inappropriate.

For example, if family members typically call the pharmacy to renew medications and make their own medical appointments, beginning to do these things for them is inappropriate for the nurse. Taking over undermines self-esteem, confidence, and success.

Nurse as Guest

Being a guest as a community/public health nurse in a family’s home does not mean that the relationship is social. The social graces for the community and culture of the family must be considered so that the family is at ease and is not offended. However, the relationship is intended to be therapeutic. For example, many older persons believe that offering something to eat or drink is important as a sign that they are being courteous and hospitable. Because your refusal to share in a glass of iced tea may be taken as an affront, you may opt to accept the tea. However, you certainly have the right to refuse, especially if infectious disease is a concern.

Validate with the client that the time of the visit is convenient. If the client fails to offer you a seat, you may ask if there is a place for you and the family to sit and talk. This place may be any room of the house or even outside in good weather.

Phases of Relationships

Relatedness and communication between the nurse and the client are fundamental to all nursing care. A nurse–client relationship with a family (rather than an individual) is critical to community/public health nursing. The phases of the nurse–client relationship with a family are the same as are those with an individual. Different schemes have been developed for naming phases of relationships. All schemes have (1) a preinitiation or preplanning phase, (2) an initiation or introductory phase, (3) a working phase, and (4) an ending phase (Arnold & Boggs, 2011). Some schemes distinguish a power and control or contractual phase that occurs before the working phase.

The initiation phase may take several visits. During this phase, the nurse and the family get to know one another and determine how the family health problems are mutually defined. The more experience the nurse has, the more efficient she or he will become; initially, many community/public health nursing students may require four to six visits to feel comfortable and to clarify their role (Barton & Brown, 1995).

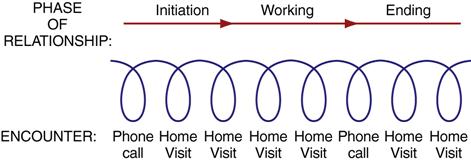

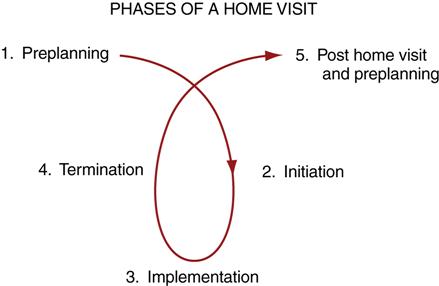

The nursing student should keep in mind that the relationship with the family usually involves many encounters over time—home visits, telephone calls, or visits at other ambulatory sites such as clinics. Several encounters may occur during each phase of the relationship (Figure 11-1). Each encounter also has its own phases (Figure 11-2).

Preplanning each telephone call and home visit is helpful. Box 11-2 lists activities in which community/public health nurses usually engage before a home visit. The list can be used as a guide in helping novice community/public health nurses organize previsit activities efficiently.

The visit begins with a reintroduction and a review of the plan for the day; the nurse must assess what has happened with the family since the last encounter. At this point, the nurse may renegotiate the plan for the visit and implement it. The end of the visit consists of summarizing, preparing for the next encounter, and leave-taking. Box 11-3 describes the community/public health nurse’s typical activities during a home visit.

Characteristics of Relationships with Families

Some differences are worth discussing in nurses’ relationships with families compared with those with individual clients in hospitals. The difference that usually seems most significant to the nurse who is learning to make home visits is the fact that the nurse has less control over the family’s environment and health-related behavior (McNaughton, 2000). The relationship usually extends for a longer period. A more interdependent relationship develops between the community/public health nurse and the family throughout all steps of the nursing process.

Families Retain Much Control

The family can control the nurse’s entry into the home by explicitly refusing assistance, establishing the time of the visit, or deciding whether to answer the door. Unlike hospitalized clients, family members can just walk away and not be home for the visit. One study of home visits to high-risk pregnant women revealed that younger and more financially distressed women tended to miss more appointments for home visits (Josten et al., 1995). Being rejected by the family is often a concern of nurses who are learning to conduct home visits. As with any relationship, anxiety can exist in relation to meeting new, unknown families. Families may actually have similar feelings about meeting the nurse and may wonder what the nurse will think of them, their lifestyle, and their health care behavior.

A helpful practice is to keep your perspective; if the clients are home for your visit, they are at least ambivalent about the meeting! If they are at home to answer the door, they are willing to consider what you have to offer.

Most families involved with home care of the ill have requested assistance. Because only a few circumstances exist (as previously discussed) in which nursing care can be forced on families, the nurse can view the home visit as an opportunity to explore voluntarily the possibility of engaging in relationships (Byrd, 1995). The nurse is there to offer services and engage the family in a dialogue about health concerns, barriers, and goals. As with all nurse–client relationships, the nurse’s commitment, authenticity, and caring constitute the art of nursing practice that can make a difference in the lives of families. Just as not all individuals in the hospital are ready or able to use all of the suggestions made to them, families have varying degrees of openness to change. If after discussing the possibilities the family declines either overtly or through its actions, the nurse has provided an opportunity for informed decision making and has no further obligation.

Goals of Nursing Care Are Long Term

A second major difference in nurse relationships with families is that the goals are usually more long term than are those with individual clients in hospitals. Clients may be in hospice programs for 6 months. A family with a member who has a recent diagnosis of hypertension may take 6 weeks to adjust to medications, diet, and other lifestyle changes. A school-aged child with a diagnosis of attention deficit disorder may take as long as half the school year to show improvement in behavior and learning; sometimes, a year may be required for appropriate classroom placement.

For some nurses, this time frame is judged to be slow and tedious. For others, the time frame is seen as an opportunity to know a family in more depth, share life experiences over time, and see results of modifications in nursing care. For nurses who like to know about a broad range of health and nursing issues, relationships with families stimulate this interest. Having had some experience in home visiting is helpful for nurses who work in inpatient settings; it allows them to appreciate the scope and depth of practice of community/public health nurses who make home visits as a part of their regular practice. These experiences can sensitize hospital nurses to the home environments of their clients and can result in better hospital discharge plans and referrals.

Because ultimate goals may take a long time to achieve, short-term objectives must be developed to achieve long-term goals. For example, a family needs to be able to plan lower-calorie menus with sufficient nutrients before weight loss is possible; a parent may need to spend time with a child daily before unruly behavior improves.

Nursing interventions in a hospital setting become short-term objectives for client learning and mastery in the home setting. In an inpatient setting, giving medications as prescribed is a nursing action. In the home, the spouse giving medications as prescribed becomes a behavioral objective for the family; the related nursing action is teaching.

Human progress toward any goal does not usually occur at a steady pace. For example, you may start out bicycling faithfully three times a week and give up abruptly. Similarly, clients may skip an insulin dose or an oral contraceptive. A family may assertively call appropriate community agencies, keep appointments, and stop abruptly. Families can be committed to their own health and well-being and yet not act on their commitment consistently. Recognizing that setbacks and discouragement are a part of life allows the community/public health nurse to be more accepting of reality and have the objectivity to renegotiate goals and plans with families. Box 11-4 includes evidence-based ways to foster goal accomplishment.

Changes are sometimes subtle or small. Success breeds success, at least motivationally. The short-term goals on which everyone has agreed are important to make clear so that the nurse and the family members have a common basis for evaluation. Goals can be set in a logical sequence, in small steps, to increase the chance of success. In an inpatient setting, the skilled nurse notices the subtle changes in client behavior and health status that can warn of further disequilibrium or can signal improvement. Similarly, during a series of home visits, the skilled nurse is aware of slight variations in home management, personal care, and memory that may presage a deteriorating biological or social condition.

Nursing Care Is More Interdependent with Families

Because families have more control over their health in their own homes and because change is usually gradual, greater emphasis must be placed on mutual goals if the nurse and family are to achieve long-term success.

Except in emergency situations, the client determines the priority of issues. A parent may be adamant that obtaining food is more important than obtaining their child’s immunization. A child’s school performance may be of greater concern to a mother than is her own abnormal Papanicolaou (Pap) smear results. Failure of the nurse to address the family’s primary priority may result in the family perceiving that the nurse does not genuinely care. At times, the priority problem is not directly health related, or the solution to a health problem can be handled better by another agency or discipline. In these instances, the empathic nurse can address the family’s stress level, problem-solving ability, and support systems and make appropriate referrals. When the nurse takes time to validate and discuss the primary concern, the relationship is enhanced.

Families are sometimes unaware of what they do not know. The nurse must suggest health-related topics that are appropriate for the family situation. For example, a young mother with a healthy newborn may not have thought about how to determine when her baby is ill. A spouse caring for his wife with Alzheimer disease may not know what safety precautions are necessary. Community/public health nurses seek to enhance family competence by sharing their professional knowledge with families and building on the family’s experience (Reutter & Ford, 1997; SmithBattle, 2009).

Flexibility is a key. Because visits occur over several days to months, other events (e.g., episodic illnesses, a neighbor’s death, community unemployment) can impinge on the original plan. Family members may be rehospitalized and receive totally new medical orders once they are discharged to home. The nurse’s clarity of purpose is essential in identifying and negotiating other health-related priorities after the first concerns have been addressed (Monsen, Radosevich, Kerr, & Fulkerson, 2011).

Increasing nurse–family relatedness

What promotes a successful home visit? What aspects of the nurse’s presence promote relatedness? What structures provide direction and flexibility? The nursing process provides a general structure, and communication is a primary vehicle through which the nursing process is manifested. The foundation for both the nursing process and communication is relatedness and caring (ANA, 2003; McNaughton, 2005; Roach, 1997; SmithBattle, 2009; Watson, 2002; Watson, 2005).

Fostering a Caring Presence

Nursing efforts are not always successful. However, by being concerned about the impact of home visits on the family and by asking questions regarding her or his own motivations, the nurse automatically increases the likelihood that home visits will be of benefit to the family. The nurse is acknowledging that the intention is for the relationship to be meaningful to both the nurse and the family.

Building and preserving relationships is a central focus of home visiting and requires significant effort (Heaman et al., 2007; McNaughton, 2000, 2005). The relatedness of nurses in community health with clients is important (Goldsborough, 1969; SmithBattle, 2009; Zerwekh, 1992).

Involvement, essentially, is caring deeply about what is happening and what might happen to a person, then doing something with and for that person. It is reaching out and touching and hearing the inner being of another…. For a nurse–client relationship to become a moving force toward action, the nurse must go beyond obvious nursing needs and try to know the client as a person and include him in planning his nursing care. This means sharing feelings, ideas, beliefs and values with the client…. Without responsibility and commitment to oneself and others…[a person] only exists. It is through interaction and meaningful involvement with others that we move into being human (Goldsborough, 1969, pp. 66-68).

Mayers (1973, p. 331) observed 16 randomly selected nurses during home visits to 37 families and reported that “regardless of the specific interaction style [of each nurse], the clients of nurses who were client-focused consistently tended to respond with interest, involvement and mutuality.” A client-focused nurse was observed as one who followed client cues, attempted to understand the client’s view of the situation, and included the client in generating solutions. Being related is a contribution that the nurse can make to the family, independent of specific information and technical skills, a contribution that students often underestimate.

Although being related is necessary, it is inadequate in itself for high-quality nursing. A community/public health nurse must also be competent. Community/public health nursing also depends on assessment skills, judgment, teaching skills, safe technical skills, and the ability to provide accurate information. As a community/public health nurse’s practice evolves, tension always exists between being related and doing the tasks. In each situation, an opportunity exists to ask, “How can I express my caring and do (perform direct care, teach, refer) what is needed?”

Barrett (1982) and Katzman and colleagues (1987) reported on the differences that students actually make in the lives of families. Barrett (1982) demonstrated that postpartum home visits by nursing students reduced costly postpartum emergency department and hospital visits. Katzman and co-workers (1987) considered hundreds of visits per semester made by 80 students in a southwestern state to families with newborns, well children, pregnant women, and members with chronic illnesses. Case examples describe how student enthusiasm and involvement contributed to specific health results.

Everything a nurse has learned about relationships is important to recall and transfer to the experience of home visiting. Carl Rogers (1969) identified three characteristics of a helping relationship: positive regard, empathy, and genuineness. These characteristics are relevant in all nurse–client relationships, and they are especially important when relationships are initiated and developed in the less-structured home setting. Presence means being related interpersonally in ways that reveal positive regard, empathy, genuineness, and caring concern.

How is it possible to accept a client who keeps a disorderly house or who keeps such a clean house that you feel as if you are contaminating it by being there? How is it possible to have positive feelings about an unmarried mother of three when you and your partner have successfully avoided pregnancy? Having positive regard for a family does not mean giving up your own values and behavior (see Chapter 10). Having positive regard for a family that lives differently from the way you do does not mean you need to ignore your past experiences. The latter is impossible. Rather, having positive regard means having the ability to distinguish between the person and her or his behavior. Saying to yourself, “This is a person who keeps a messy house” is different from saying, “This person is a mess!” Positive regard involves recognizing the value of persons because they are human beings. Accept the family, not necessarily the family’s behavior. All behavior is purposeful; and without further information, you cannot determine the meaning of a particular family behavior. Positive regard involves looking for the common human experiences. For example, it is likely that both you and client family members experience awe in the behavior of a newborn and sadness in the face of loss.

Empathy is the ability to put yourself in someone else’s shoes and to be able to walk in her or his footsteps so as to understand her or his journey. “Empathy requires sensitivity to another’s experience…including sensing, understanding, and sharing the feelings and needs of the other person, seeing things from the other’s perspective” according to Rogers (cited in Gary & Kavanagh, 1991, p. 89). Empathy goes beyond self and identity to acknowledge the essence of all persons. It links a characteristic of a helping relationship with spirituality or “a sense of connection to life itself” (Haber et al., 1987, p. 78). Empathy is a necessary pathway for our relatedness.

However, what does understanding another person’s experience mean? More than emotions are involved. A person’s experience includes the sense that she or he makes of aspects of human existence (SmithBattle, 2009; van Manen, 1990). Being understood means that a person is no longer alone (Arnold, 1996). Being understood provides support in the face of stress, illness, disability, pain, grief, and suffering. When a client feels understood in a nurse–client partnership (side-by-side relationship), the client’s experience of being cared for is enhanced (Beck, 1992).

To understand another person’s experience, you must be able to imagine being in her or his place, recognize commonalities among persons, and have a secure sense of yourself (Davis, 1990). Being aware of your own values and boundaries is helpful in retaining your identity in your interactions with others. To understand another individual’s experience, you must also be willing to engage in conversation to negotiate mutual definitions of the situation. For example, if you are excited that an older person is recovering function after a stroke, but the person’s spouse sees only the loss of an active travel companion, a mutual definition of the situation does not exist. Empathy will not occur unless you can also understand the spouse’s perspective.

As human beings, we all like to perceive that we have some control in our environment, that we have some choice. We avoid being dominated and conned. The nurse’s genuineness facilitates honesty and disclosure, reduces the likelihood that the family will feel betrayed or coerced, and enhances the relationship. Genuineness does not mean that you speak everything that you think. Genuineness means that what you say and do is consistent with your understanding of the situation.

The nurse can promote genuine self-expression in others by creating an atmosphere of trust, accepting that each person has a right to self-expression, “actively seeking to understand” others, and assisting them to become aware of and understand themselves (Goldsborough, 1969, p. 66). When family members do not believe that being genuine with the nurse is safe, they may tell only what they think the nurse would like to hear. This action makes developing a mutual plan of care much more difficult.

The reciprocal side of genuineness is being willing to undertake a journey of self-expression, self-understanding, and growth. Tamara, a recent nursing graduate, wrote about her growing self-responsibility:

This student, who preferred predictable environments, was able to confront her anxiety and anger in environments in which much was beyond her control. A mother was not interested in the student’s priorities. A family abruptly moved out of the state in the middle of the semester. Nonetheless, the student was able to respond in such circumstances. She became more responsible, and she was able to temper her judgment and work with the mother’s concern. When the family moved, the student experienced frustration and anger that she would not see the “fruits of her labor” and that she would “have to start over” with another family. However, her ability to respond increased because of her commitment to her own growth, relatedness with families, and desire to contribute to the health and well-being of others.

In a context of relating with and advocating for the family, the relationship becomes an opportunity for growth in both the nurse’s and the family’s lives (Glugover, 1987). Imagine standing side-by-side with the family, being concerned for their well-being and growth. Now imagine talking to a family face-to-face, attempting to have them do things your way. The first image is a more caring and empathic one.

Creating Agreements for Relatedness

How can communications be structured to increase the participation of family members? Without the family’s engagement, the community/public health nurse will have few positive effects on the health behavior and health status of the family and its members.

Nurses are expert in caring for the ill; in knowing about ways to cope with illness, to promote health, and to protect against specific diseases; and in teaching and supporting family members. Family members are experts in their own health. They know the family health history, they experience their health states, and they are aware of their health-related concerns.

Through the nurse–family relationship, a fluid process takes place of matching the family’s perceived needs with the nurse’s perceptions and professional judgments about the family’s needs. Paradoxically, the more skilled the nurse is in forgetting her or his own anxiety about being the good nurse, the more likely the nurse is to listen to the family members, validate their reality, and negotiate an adequate, effective plan of care.

One study of home visits revealed that more than half of the goals stated by public health nurses to the researcher could not be detected, even implicitly, during observations of the home visits. Therefore, half the goals were known only to the nurse and were, therefore, not mutual. The more specifically and concretely the goals were stated by the nurse to the researcher, the greater would be the likelihood that the clients understood the nurse’s purposes (Mayers, 1973). To negotiate mutual goals, the client needs to understand the nurse’s purposes.

The initial letter, telephone call, or home visit is the time to share your ideas with the family about why you are contacting them. During the first interpersonal encounter by telephone or home visit, explore the family members’ ideas about the purpose of your visits. This phase is essential in establishing a mutually agreed on basis for a series of encounters. As a result of her qualitative research study of maternal-child home visiting, Byrd (2006, p. 271) stated that “people enter…relationships with the expectation of receiving a benefit” that may be information, status, service, or goods. Byrd asserted that it is important for nurses to create client expectations through previsit publicity about (marketing) home-visiting programs. Also it is essential to understand the expectations of the specific persons being visited.

Family members may have had previous relationships with community/public health nurses and students. Family members may be able to share such information as what they found to be most helpful, why they are willing to work with a nurse or student again, and what goals they have in mind. Other families who have had no prior experience with community/public health nurses may not have specific expectations. Asking is important.

A contract is a specific, structured agreement regarding the process and conditions by which a health-related goal will be sought. In the beginning of most student learning experiences, the agreement usually entails one or more family members continuing to meet with the nursing student for a specific number of visits or weeks. Initially, specific goals and the nurse’s role regarding health promotion and illness prevention may be unclear. (If this role was already clear, undergoing a period of study and orientation would be unnecessary.)

Initially, the agreement may be as simple as, “We will meet here at your house next Tuesday at 11:00 AM until around noon to continue to discuss what I can offer related to your family’s health and what you’d like. We can get to know each other better. We can talk more about how the week has gone for you and your family with your new baby.” These statements are the nurse’s oral offer to meet under specific conditions of time and place. The process of mutual discussion is mentioned. The goals remain general and implicit: fostering the family’s developmental task of incorporating an infant and fostering family–nurse relatedness. For the next week’s contract to be complete, the family member or members would have to agree. The most important element initially is whether agreement about being present at a specific time and place can be reached. If 11:00 AM is not workable for the family, would another time during the day when you both are available be mutually agreeable? For families who do not focus as much on the future, a community/public health nurse needs to be more flexible in scheduling the time of each visit.

The word contract often implies legally binding agreements. This is not true of nurse–client contracts. Nurses are legally and ethically bound to keep their word in relation to nursing care; clients are not legally bound to keep their agreements. However, establishing a mutual agreement for relating increases the clarity of who will do what, when, where, for what purposes, and under what conditions. Because of some people’s negative response to the word contract, agreement or discussion of responsibilities may be better.

An agreement may be oral or written. For some families, written agreements, especially early in the relationship, may be perceived as a threat. For example, a family that has been conned by a household repair scheme may be very suspicious of written agreements. Family members who are not legal citizens may not want to sign an agreement for fear that if it is not kept they will be punished. Do not push for a written agreement if the family is uncomfortable. If you do notice such discomfort, this may be a good opportunity to explore their fears. Written agreements are required when insurance is paying for the care provided by nurses working with home health agencies and to comply with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Helgeson and Berg (1985) describe factors affecting the contracting process by studying a small convenience sample of 15 community/public health nursing students and 12 client responses. Of the 11 students who introduced the idea of a contract to clients, all did so between the second and the fourth visits of a 16-week series of visits; 9 students did so orally rather than in writing. No specific time was the best. Eight clients were very receptive to the idea because they liked the idea of establishing goals to work toward and felt the contract would serve as a reminder of their responsibility. The very process of developing a draft agreement to present to families provides the novice practitioner with an increased focus of care, clarity of nurse and family responsibilities and activities, and a basis from which to negotiate modifications in client behaviors (Helgeson & Berg, 1985; Sheridan & Smith, 1975).

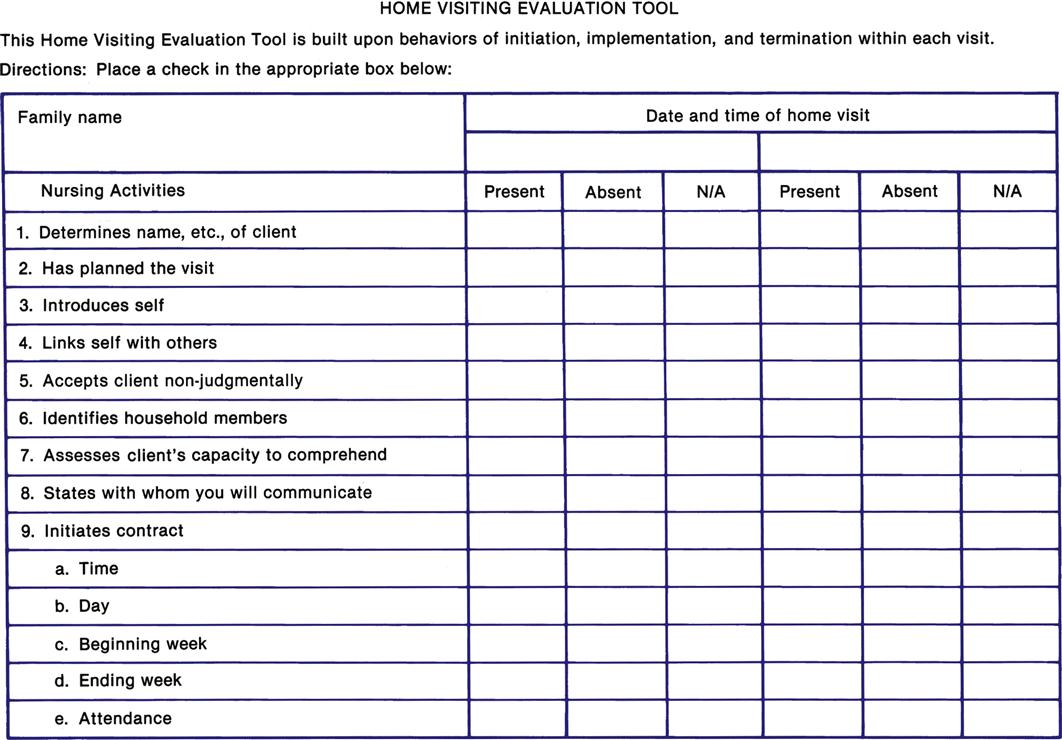

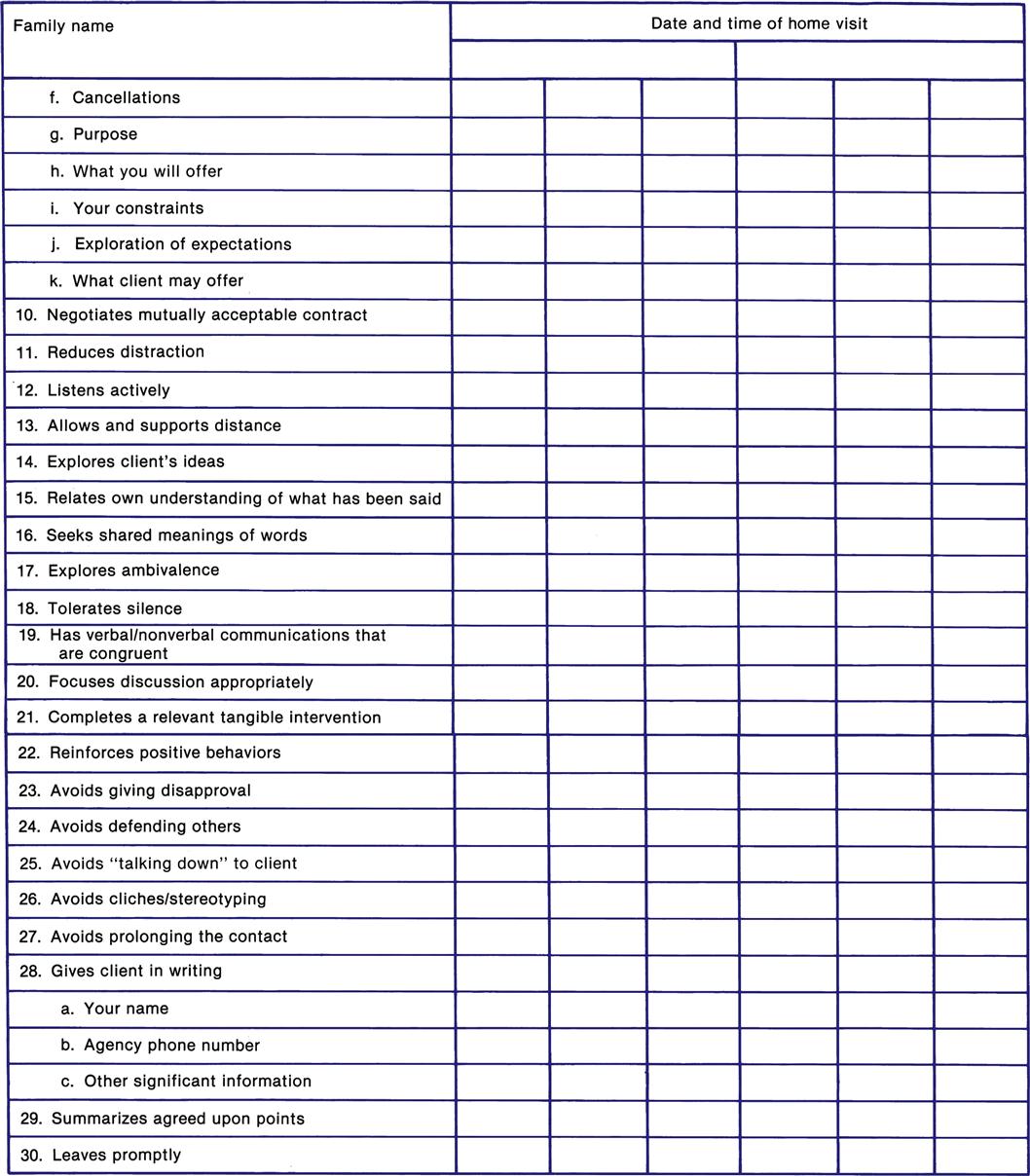

The Home Visiting Evaluation Tool in Figure 11-3 lists nurse behaviors that are appropriate for home visits, especially initial home visits and those early in a series of home visits. Nurses can use this list as a preplanning tool to identify their readiness to conduct a specific home visit. Additionally, students and community/public health nurses have used the tool to evaluate initial home visits and identify their behaviors that were omitted and needed to be included on the second home visits. The tool also has been used jointly as an evaluation tool by nurses and supervisors and students and faculty.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree