Robert J. Kizior, Janice Heinssen and Patricia Lincoln • Identify the risk factors for HIV transmission. • Explain specific issues of medication adherence to antiretroviral agents. • Discuss the nurse’s role in medication management and issues of adherence. • Explain prophylactic treatment for opportunistic infections. • Apply the nursing process, including teaching, to the care of patients with HIV infection. adherence, p. 470 antiretroviral, p. 473 antiretroviral therapy, p. 470 assembly, p. 472 budding, p. 472 combination antiretroviral therapy, p. 470 CCR5 antagonists, p. 473 CD4 T-cells, p. 472 entry (fusion) inhibitors, p. 473 highly active antiretroviral therapy, p. 470 immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, p. 478 immune response, p. 470 immune system, p. 472 integrase, p. 472 integrase inhibitors, p. 473 non-nucleoside analogues, p. 474 nucleoside/nucleotide analogues, p. 474 opportunistic infection, p. 485 Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, p. 485 postexposure prophylaxis, p. 486 protease, p. 472 protease inhibitors, p. 473 resistance, p. 470 reverse transcriptase, p. 472 reverse transcriptase inhibitors, p. 473 viral load, p. 472 Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) was first reported in the United States in 1981 and has led to the death of more than 25 million people globally since 1981. In 2009, an estimated 1.8 million deaths occurred, including 260,000 children younger than 15 years. It is estimated that 33.3 million people worldwide were living with HIV in 2009. The annual number of new HIV infections was 2.6 million in 2009, a reduction from 3 million in 2001. In the United States, it is estimated that at the end of 2009, 1.5 million people were living with HIV/AIDS, and that 210,000 people are unaware that they are HIV infected. Significant improvement in HIV-related morbidity and mortality and a reduction in perinatal and behaviorally associated HIV transmission have become possible with combination antiretroviral therapy. Attaining viral suppression of HIV necessitates the use of at least two and preferably three active drugs from two or more drug classes. This is referred to as highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), or antiretroviral therapy (ART). Patients who engage and are retained in HIV care and treatment can now experience HIV as a chronic illness rather than a disease of death and dying. In the United States, approximately 30% of people living with HIV/AIDS are age 50 years or older. Areas of concern in older HIV patients are as follows: Although strides have been made in the treatment of HIV/AIDS, challenges remain. One important aspect is increased drug resistance to current therapies. The makeup of the HIV DNA strands allows the virus to mutate from a drug-sensitive to a drug-resistant form. The patient is encouraged to achieve >95% medication adherence to minimize medication resistance, but studies suggest that 6% to 16% of patients who are naïve to ART have pre-existing genotypic resistance. Nursing and public health initiatives should incorporate harm-reduction education to further minimize transmission of resistant virus (e.g., safer sex, not sharing needles or drug works, needle exchange programs). HIV is an RNA retrovirus. It is unable to survive and replicate unless it is inside a living human cell. HIV destroys CD4+ T cells (also called helper T cells or CD4 + T lymphocytes), which play a critical role in the human immune response through recognition of infectious and neoplastic processes. The destruction of CD4 cells by HIV results in immune deficiency. The CD4 cell count is an indicator for immune function in those with HIV. Normal CD4 counts range from 800 to 1200 cells/mm3. After initial infection, there is rapid viral replication, resulting in a high level of virus in peripheral blood (viral load). There is a corresponding drop in CD4 cells, which triggers an immune response, resulting in CD4 cell replacement and HIV antibody production. The viral load drops with establishment of immune response. Symptoms range from mild to severe (fever, fatigue, pharyngitis, myalgia or arthralgia, lymphadenopathy, headache, night sweats) in those recently infected with HIV and can be experienced 2 to 12 weeks after HIV exposure. This period is called acute retroviral syndrome, acute seroconversion syndrome, or primary HIV infection. Symptoms in this stage can often be mistaken by both patient and health care provider for a transient flulike illness. Consequently, few people are diagnosed during this time. Additionally, the time delay from infection to a positive HIV test result averages 10 to 14 days, but some do not seroconvert for 3 to 4 weeks. Almost all patients seroconvert within 6 months. This time delay between infection and positive test results is known as the window period. For this reason, patients who are at risk for HIV infection and test negative should be counseled to have the test repeated in 3 months (the close of the window period). If HIV is strongly suspected, an HIV RNA quantitative test can be done. A high viral load would support HIV diagnosis (>10,000 c/mL and usually >100,000 c/mL). Over time and in the absence of treatment, HIV infection generally progresses slowly with a gradual decline in CD4 cells. AIDS is a diagnosis that indicates advanced disease. The 1993 AIDS surveillance case definition includes all patients with a CD4 count <200 cells/mm3 or <14% of total lymphocytes, or one of the other AIDS-defining conditions listed in Table 35-1. The risk of opportunistic infection increases when CD4 counts fall below 200 cells/mm3. TABLE 35-1 CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM FOR HIV INFECTION* ≥, Greater than or equal to; <, less than. Category B consists of symptomatic conditions in an HIV-infected adolescent or adult that are not included in category C and are attributed to HIV infection or are considered to have a clinical course complicated by HIV infection. Examples of conditions in category B include, but are not limited to, the following: • Candidiasis, oropharyngeal (thrush) • Candidiasis, vulvovaginal; persistent, frequent, or poorly responsive to therapy • Cervical dysplasia (moderate or severe)/cervical carcinoma in situ • Constitutional symptoms, such as fever (101.3° F or 38.5° C) or diarrhea lasting longer than 1 month • Herpes zoster (shingles), involving at least two distinct episodes or more than one dermatome • Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura • Pelvic inflammatory disease, particularly if complicated by tubo-ovarian abscess • Bacterial pneumonia, recurrent (two or more episodes in 12 months) • Candidiasis of the bronchi, trachea, or lungs • Cervical carcinoma, invasive, confirmed by biopsy • Coccidioidomycosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary • Cryptococcosis, extrapulmonary • Cryptosporidiosis, chronic intestinal • Herpes simplex: chronic ulcers or bronchitis, pneumonitis, or esophagitis • Histoplasmosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary • Lymphoma, Burkitt, immunoblastic, or primary central nervous system • Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) or M. kansasii, disseminated or extrapulmonary • Mycobacterium tuberculosis, pulmonary or extrapulmonary • Pneumocystis jiroveci (formerly carinii) pneumonia (PCP) • Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) • Salmonella septicemia, recurrent *The revised CDC classification system for HIV-infected adolescents and adults categorizes persons on the basis of CD4 T-lymphocyte counts and clinical conditions associated with HIV infection. The system is based on three ranges of CD4 T-lymphocyte counts and three clinical categories (Categories A to C). From the Department of Health and Human Services, Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation: Panel on practices for treatment of HIV infection: guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-infected adults and adolescents, Dec 1, 1998. The phases of the HIV life cycle (Figure 35-1) are (1) binding and fusion: HIV begins its life cycle when it binds to a CD4 receptor and one of two co-receptors on the surface of a CD4 T-lymphocyte. The virus then fuses with the host cell. After fusion, the virus releases RNA, its genetic material, into the host cell; (2) reverse transcription: An HIV enzyme called reverse transcriptase (RT) converts the single-stranded HIV RNA to a double-stranded HIV DNA; (3) integration: The newly formed HIV DNA enters the host cell’s nucleus, where an HIV enzyme called integrase “hides” the HIV DNA within the host cell’s own DNA. The integrated HIV DNA is called a provirus; (4) transcription: When the host cell receives a signal to become active, the provirus uses a host enzyme called RNA polymerase to create copies of the HIV genomic material, as well as shorter strands of RNA called messenger RNA (MRNA). The mRNA is used as a blueprint to make long chains of HIV proteins; (5) assembly: An HIV enzyme called protease cuts the long chains of HIV proteins into smaller individual proteins. As the smaller HIV proteins come together with copies of HIV’s RNA genetic material, a new virus particle is assembled; (6) budding: The newly assembled virus pushes out (“buds”) from the host cell. During budding, the new virus steals part of the cell’s outer envelope. This envelope, which acts as a covering, is studded with protein/sugar combinations called HIV glycoproteins. These HIV glycoproteins are necessary for the virus to bind to CD4 and co-receptors. The immature virus breaks free of the infected cell; (7) maturation: The protease enzyme finishes cutting HIV protein chains into individual proteins that combine to make a new working virus. The new copies of HIV can now move on to infect other cells. HIV is spread via intimate contact with blood, semen, vaginal fluids, and breast milk. Transmission of the virus occurs primarily by: (1) sexual contact (includes oral, vaginal, and anal sex); (2) direct blood contact (intravenous drug use with shared needles, shared drug works, shared contaminated personal care items such as razors, and blood transfusions [now extremely rare in the United States]); and (3) mother to child (through shared maternal-fetal blood circulation, by direct blood contact during delivery, or in breast milk). Included in these modes are accidental needle injury, artificial insemination with donated semen, and organ transplant. HIV is not spread by casual contact (e.g., hugging), by touching items previously touched by a person infected with the virus, or during participation in sports. Those at highest risk include persons engaging in unprotected sex, those with multiple sexual partners (either the patient themselves or partner[s] of the patient), intravenous drug users who share needles or drug works, and infants born to women with HIV. The risk of mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) is 25% without ART; the risk decreases to 1% to 2% with successful use of ART. Other factors that increase the risk of MTCT are mother with a viral load >1000 copies/mL at delivery, premature rupture of the membranes, hepatitis C virus co-infection, preterm gestation, and vaginal delivery. Several laboratory tests are important for initial patient evaluation upon entry to care, during follow-up evaluation for those not on ART, and before and after initiation or modification of ART to assess for immunologic and virologic efficacy of treatment. The laboratory tests used to determine when to initiate medication therapy and to monitor efficacy of therapy and indications for changing therapy are CD4 T-cell count, plasma HIV RNA quantitative assay (or viral load [VL] test), and HIV resistance testing. The count reflects the number of CD4 cells circulating in the blood. The result is listed as an absolute number and a relative percentage. The absolute count can vary in the same patient depending on laboratory used, time of day laboratory blood work is drawn, or acute illness. The CD4 percentage is a more stable reflection of the immune system and is used in conjunction with the absolute count to monitor health status and response to medication therapy. The patient should be encouraged to use the same laboratory at approximately the same time of day to promote consistency of results. The nurse should monitor the laboratory used, because lab value references vary from laboratory to laboratory. The HIV viral load is indicative of the level of virus circulating in the blood and is the best determinant of treatment efficacy. Two FDA-approved commercially available assays commonly used are the quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay and the branched-chain DNA. A key goal of therapy is to achieve and maintain a viral load below the limits of detection (<20 to 40 copies/mL, depending on assay used). This goal should be achieved in 16 to 24 weeks of therapy. Resistance to antiretroviral medications leads to treatment failure and to risk of transmitting drug-resistant virus. Determination of the presence of a drug-resistant strain of HIV is important to prevent ineffective medication treatment. Two types of testing are available: Genotypic resistance testing identifies mutations in the genetic code of HIV associated with drug resistance. Phenotypic testing determines if the patient’s HIV is able to replicate in the presence of specific antiretroviral medications. Genotypic resistance testing is recommended upon entry into care, regardless of whether ART will be started immediately. Screening for HLA-B5701 determines if the patient has a mutation associated with a hypersensitivity reaction to abacavir (Ziagen). Those with a positive HLA-B5701 result should not receive abacavir and should have it listed as a drug allergy. This test should be done and results reviewed before abacavir is considered as part of a treatment regimen. A viral tropism assay should be done before initiation of a CCR5 antagonist medication. HIV disease staging and classification systems are important tools for tracking and monitoring the HIV epidemic and providing the clinician and patient with information about HIV disease stage and clinical management. The two major classification systems are the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) staging system (revised in 1993 and 2008) and the World Health Organization (WHO) system (last revised in 2007). In December 2008, CDC published Revised Surveillance Case Definitions for HIV Infection Among Adults, Adolescents, and Children Aged <18 Months and for HIV Infection and AIDS Among Children Aged 18 Months to <13 Years—United States, 2008 (www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5710a1.htm). The CDC system assesses the severity of HIV disease by CD4 cell counts and by presence of specific HIV-related conditions; the system is based on the lowest documented CD4 cell count (nadir CD4) and on previously diagnosed HIV-related conditions. The WHO system is useful in resource-constrained settings without access to CD4 cell measurements and classifies HIV disease on the basis of clinical manifestations that clinicians and those with varying levels of HIV expertise and training can recognize in diverse settings. The primary goals for initiating ART are to reduce HIV-associated morbidity and mortality and prolong the duration and quality of life; restore and preserve immunologic function; maximally and durably suppress plasma HIV viral load; and prevent HIV transmission. Recommendations for HIV management, including initiation and ongoing treatment with antiretroviral medications, change rapidly based on updated clinical data and expert medical opinion. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV 1 Infected Adults and Adolescents have been developed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Expert Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. This panel recommends ART for all HIV-infected individuals. The strength of this recommendation varies based on pretreatment CD4 cell count; however, regardless of CD4 count, ART is strongly recommended for HIV-infected pregnant patients; for those with a history of an AIDS-defining illness, HIV-associated nephropathy, or HIV and hepatitis B coinfection; and for serodiscordant couples. The panel posts updated information regularly at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov. With increased treatment options and a better understanding of the risks of untreated HIV infection or uncontrolled viremia, there is a shift toward earlier consideration of ART. Suppression of HIV with ART may decrease inflammation and immune activation that is thought to contribute to higher rates of cardiovascular, kidney, and liver disease, neurologic complications, and malignancy in HIV-infected cohorts. If therapy is to be initiated, medications are selected based on results of genotypic resistance testing where applicable; co-morbidities (e.g., liver disease, renal dysfunction, depression); potential drug-drug interactions; pregnancy status; and assessment of patient’s willingness and readiness to start therapy. Evaluation of medication readiness should include dosage regimen, pill burden, dosing frequency, food restrictions, side effects, and patient’s daily routine. Tools for promoting medication adherence (e.g., alarms, pill planners) and plans for management of potential medication side effects should be reviewed before medication initiation. The patient should be instructed in the need for >95% medication adherence, the potential for development of medication resistance with less than optimal adherence, and clinical implications of resistance. Reverse transcriptase inhibitors, protease inhibitors (PIs), entry (fusion) inhibitors, CCR5 antagonists, and integrase inhibitors make up the classification of drugs known as antiretroviral therapy. Reverse transcriptase inhibitors (RT inhibitors) are further divided into nucleoside/nucleotide (NRTI) analogues and non-nucleoside (NNRTI) analogues. More than 20 different antiretroviral agents are FDA approved, and various agents are available in fixed-dose combinations that contain two or more HIV medications from one or more drug classes. PIs have changed the prognosis for millions of patients infected with HIV. PIs combined with RT inhibitors can reduce viral plasma levels to undetectable levels, offering significant clinical benefits. The most recent additions include maraviroc (Selzentry) a CCR5 antagonist; raltegravir (Isentress) and dolutegravir (Tivicay), integrase inhibitors; and etravirine (Intelence) and rilpivirine (Edurant), nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Since the 1980s, when zidovudine monotherapy showed survival benefits in advanced HIV patients, much progress has been made. Newer agents have improved adherence (e.g., fewer pills for more convenient dosing, formulation changes that reduce dosing frequency or pill burden, combination dosage forms with two or three drugs in one pill). Other improvements include increased potency, improved side-effect profile (e.g., decreased gastrointestinal effects), and protease-inhibitor boosting with ritonavir. ART is the standard of care in the treatment of HIV infection. The following combinations are preferred regimens for antiretroviral-naïve patients: Seven NRTIs are approved for use in the United States: zidovudine (Retrovir), didanosine (Videx), stavudine (Zerit), lamivudine (Epivir), abacavir (Ziagen), tenofovir (Viread), and emtricitabine (Emtriva). Six fixed-dose combination products are also available: Combivir (lamivudine/zidovudine), Trizivir (Abacavir/lamivudine/zidovudine), Epzicom (abacavir/lamivudine), Atripla (efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir), Truvada (emtricitabine/tenofovir), and Complera (rilpivirine/emtricitabine/tenofovir). Tenofovir (Viread) is the only nucleotide analogue. NRTIs, the foundation of ART, act by interfering with HIV viral RNA-dependent DNA polymerase, resulting in inhibition of viral replication. Two of these agents are typically included in initial ART regimens. The preferred dual NRTI is tenofovir/emtricitabine (or zidovudine/lamivudine in pregnant patients). All NRTIs except didanosine should be taken with food for optimal tolerability. Didanosine should be taken 60 minutes before meals or 2 hours after meals for optimal absorption. With the exception of abacavir, NRTIs require dosage adjustment in persons with renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance <50 mL/min). Similarly, fixed-dose NRTI combinations should be avoided in patients with renal insufficiency. Gastrointestinal side effects (e.g., nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain) are transient and improve within the first 2 weeks of therapy. As a class, NRTIs are associated with changes in the body’s metabolism secondary to mitochondrial toxicity. Complications include peripheral neuropathy, myopathy, pancreatitis, and lipoatrophy. Lipoatrophy, or wasting of fat on the extremities, face, and buttocks, is associated with chronic NRTI administration. Rare fatalities have occurred owing to lactic acidosis and hepatic steatosis associated with NRTIs. Drug interactions are uncommon with NRTIs. Gastrointestinal complaints and mitochondrial toxicity are less likely to occur with tenofovir. The most serious side effect with tenofovir is renal toxicity, which occurs rarely. Adherence with NRTIs can be improved with once-daily dosing (possible with abacavir, didanosine, emtricitabine, lamivudine, and tenofovir) and with fixed-dosage combination products (e.g., Combivir and Truvada). Prototype Drug Chart 35-1 gives pharmacologic data for zidovudine, and Prototype Drug Chart 35-2 shows the data for tenofovir.

HIV- and AIDS-Related Drugs

Objectives

Key Terms

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/KeeHayes/pharmacology/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/KeeHayes/pharmacology/

HIV Infection: Pathophysiology

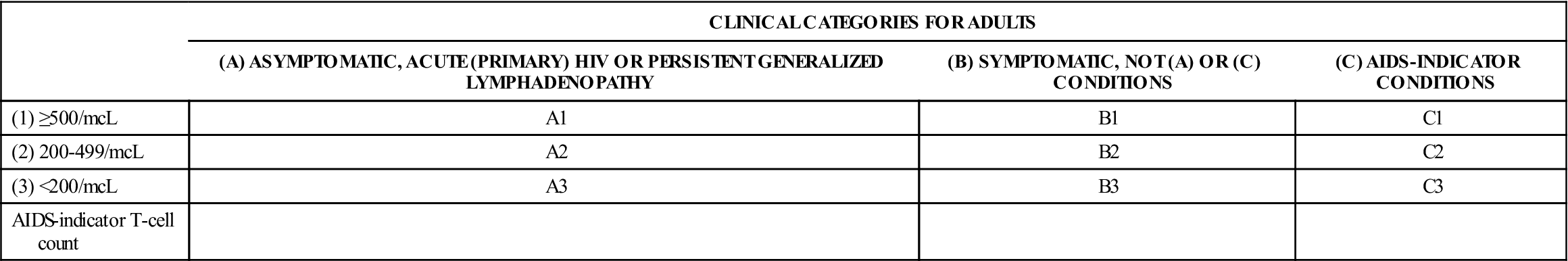

CLINICAL CATEGORIES FOR ADULTS

(A) ASYMPTOMATIC, ACUTE (PRIMARY) HIV OR PERSISTENT GENERALIZED LYMPHADENOPATHY

(B) SYMPTOMATIC, NOT (A) OR (C) CONDITIONS

(C) AIDS-INDICATOR CONDITIONS

(1) ≥500/mcL

A1

B1

C1

(2) 200-499/mcL

A2

B2

C2

(3) <200/mcL

A3

B3

C3

AIDS-indicator T-cell count

CD4 T-LYMPHOCYTE CATEGORIES

HIV-infected persons should be classified based on existing guidelines for the medical management of HIV-infected persons; thus, the lowest accurate CD4 T-lymphocyte count (but not necessarily the most recent) should be used for classification purposes.

Clinical Categories

Category A consists of one or more of the following conditions in an adolescent or adult (13 years of age or older) with documented HIV infection. Conditions listed in categories B and C must not have occurred.

For classification purposes, category B conditions take precedence over category A conditions.

Category C includes the clinical conditions listed in the AIDS surveillance case definition. For classification purposes, once a category C condition occurs, the person remains in category C.

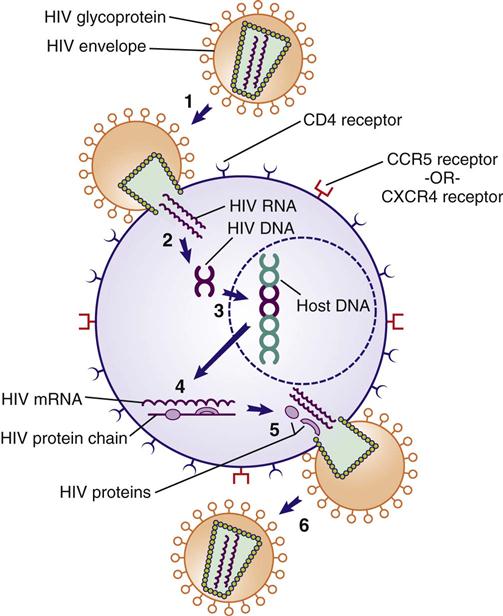

HIV Life Cycle

HIV Transmission

Laboratory Testing

HIV Resistance Testing

Additional Laboratory Evaluation

Classification

Treatment Goals

Indications for Antiretroviral Therapy

Classes of Antiretroviral Medications

Antiretroviral Agents

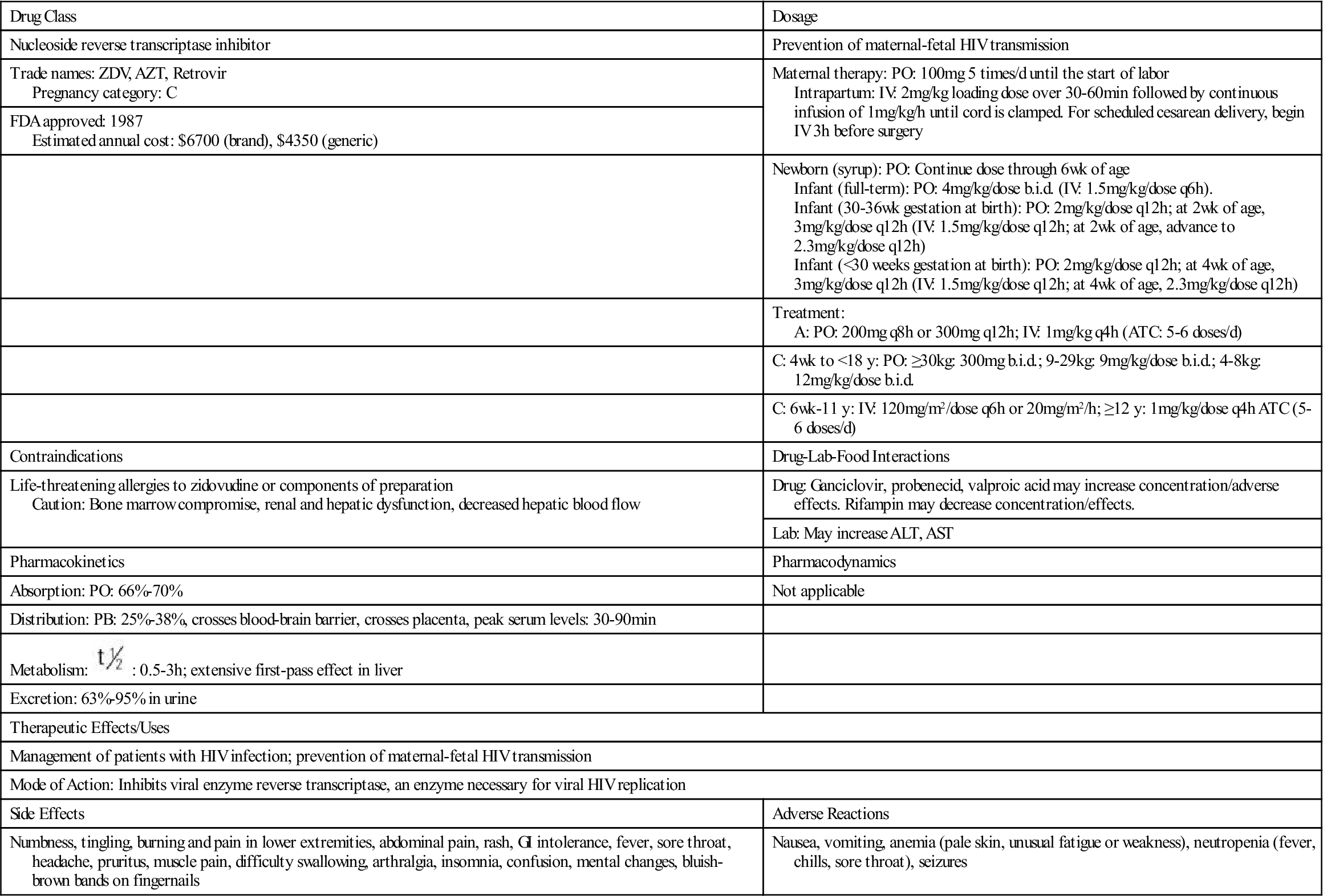

Nucleoside/Nucleotide Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors

HIV- and AIDS-Related Drugs

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

: 0.5-3 h; extensive first-pass effect in liver

: 0.5-3 h; extensive first-pass effect in liver

, half-life; wk, week; y, year; >, greater than; ≥, greater than or equal to; <, less than.

, half-life; wk, week; y, year; >, greater than; ≥, greater than or equal to; <, less than.