History of Public Health and Public and Community Health Nursing

Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to do the following:

1. Interpret the focus and roles of public health nurses through a historical approach.

2. Trace the ongoing interaction between the practice of public health and that of nursing.

Key Terms

American Nurses Association, p. 36

American Public Health Association, p. 29

American Red Cross, p. 28

district nursing, p. 25

district nursing association, p. 26

Florence Nightingale, p. 25

Frontier Nursing Service, p. 30

Lillian Wald, p. 27

Mary Breckinridge, p. 30

Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, p. 30

National League for Nursing, p. 36

National Organization for Public Health Nursing, p. 29

official (health) agencies, p. 32

settlement houses, p. 27

Sheppard-Towner Act, p. 30

Social Security Act of 1935, p. 32

Town and Country Nursing Service, p. 28

visiting nurse, p. 26

William Rathbone, p. 26

—See Glossary for definitions

Janna Dieckmann, PhD, RN

Janna Dieckmann, PhD, RN

Janna Dieckmann began her nursing practice in 1974 as a public health nurse with the Visiting Nurse Association of Cleveland, Ohio, and also practiced many years with the Visiting Nurse Association of Philadelphia. Today she is a clinical associate professor at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where she teaches public health nursing, health promotion, and health policy. She uses written and oral historical materials to research the history of public health nursing and care of the chronically ill, and to comment on contemporary health policy.

Nurses use historical approaches to examine both the profession’s present and its future. In doing so, several different questions are asked: First, who is the population-centered nurse? In the past, population-centered nurses have been called public health nurses, district nurses, and visiting nurses; sometimes they have even been called school nurses, occupational health nurses, and home health nurses. Second, how does the past contribute to who the population-centered nurse is today? Next, what are the places and times in which these nurses have worked and continue to work? When a conscious process of critique and insight is used to look into past actions of the specialty, what can be discovered? Must contemporary nurses agree with or endorse past actions of the profession? And last, how might knowledge of population-centered nursing history serve not only as a source of inspiration, but also as a creative stimulus to solve the new and enduring problems of the current period? This chapter serves as an introduction to these questions through tracing the development of population-centered nursing and the evolution of this approach to nursing practice.

Change and Continuity

For more than 125 years, public health nurses in the United States have worked to develop strategies to respond effectively to prevailing public health problems. The history of population-centered nursing reflects changes in the specific focus of the profession while emphasizing continuity in approach and style. Nurses have worked in communities to improve the health status of individuals, families, and populations, especially those who belong to vulnerable groups. Part of the appeal of this nursing specialty has been its autonomy of practice and independence in problem solving and decision making, conducted in the context of a multidisciplinary practice. Many varied and challenging public health nursing roles originated in the late 1800s when public health efforts focused on environmental conditions such as sanitation, control of communicable diseases, education for health, prevention of disease and disability, and care of aged and sick persons in their homes.

Although the manifestations of these threats to health have changed over time, the foundational principles and goals of public health nursing have remained the same. Many communicable diseases, such as diphtheria, cholera, and typhoid fever, have been largely controlled in the United States, but others continue to affect many lives, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), tuberculosis, and hepatitis. Emerging communicable diseases, such as H1N1 influenza, underscore the truth that health concerns are international. Even though environmental pollution in residential areas has been reduced, communities are now threatened by overcrowded garbage dumps and pollutants affecting the air, water, and soil. Natural disasters continue to challenge public health systems, and bioterrorism and other human-made disasters threaten to overwhelm existing resources. Research has identified means to avoid or postpone chronic disease, and nurses implement strategies to modify individual and community risk factors and behaviors. Finally, with the growing population percentage of older adults in the United States and their preference to remain at home, additional nursing services are required to sustain the frail, the disabled, and the chronically ill in the community.

Contemporary nursing roles in the United States developed from several sources and are a product of various ongoing social, economic, and political forces. This chapter describes the societal circumstances that influenced nurses to establish community-based and population-centered practices. For the purposes of this chapter, the term nurse will be used to refer to nurses who rely heavily on public health science to complement their focus on nursing science and practice. The nation’s need for community and public health nurses, the practice of population-centered nursing, and the organizations influencing public health nursing in the United States from the nineteenth century to the present are discussed.

Public Health During America’s Colonial Period and the New Republic

Concern for the health and care of individuals in the community has characterized human existence. All people and all cultures have been concerned with the events surrounding birth, death, and illness. Human beings have sought to prevent, understand, and control disease. Their ability to preserve health and treat illness has depended on the contemporary level of science, use and availability of technologies, and degree of social organization.

In the early years of America’s settlement, as in Europe, the care of the sick was usually informal and was provided by household members, almost always women. The female head of the household was responsible for caring for all household members, which meant more than nursing them in sickness and during childbirth. She was also responsible for growing or gathering healing herbs for use throughout the year. For the increasing numbers of urban residents in the early 1800s, this traditional system became insufficient.

American ideas of social welfare and the care of the sick were strongly influenced by the traditions of British settlers in the New World. Just as American law is based on English common law, colonial Americans established systems of care for the sick, poor, aged, mentally ill, and dependents based on England’s Elizabethan Poor Law of 1601. In the United States, as in England, local poor laws guaranteed medical care for poor, blind, and “lame” individuals, even those without family. Early county or township government was responsible for the care of all dependent residents but provided almshouse charity carefully, economically, and only for local residents. Travelers and wanderers from elsewhere were returned to their native counties for care. The few hospitals that existed were found only in the larger cities. In 1751, Pennsylvania Hospital was founded in Philadelphia, the first hospital in what would become the United States.

Early colonial public health efforts included the collection of vital statistics, improvements to sanitation systems, and control of any communicable diseases introduced through seaports. Colonists lacked a continuing and organized mechanism for ensuring that public health efforts would be supported and enforced. Epidemics intermittently taxed the limited local organization for health during the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries (Rosen, 1958).

After the American Revolution, the threat of disease, especially yellow fever, brought public support for establishing government-sponsored, or official, boards of health. New York City, with a population of 75,000 by 1800, had established basic public health services, which included monitoring water quality, constructing sewers and a waterfront wall, draining marshes, planting trees and vegetables, and burying the dead (Rosen, 1958).

Increased urbanization and beginning industrialization in the new United States contributed to increased incidence of disease, including epidemics of smallpox, yellow fever, cholera, typhoid, and typhus. Tuberculosis and malaria remained endemic at a high incidence rate, and infant mortality was about 200 per 1000 live births (Pickett and Hanlon, 1990). American hospitals in the early 1800s were generally unsanitary and staffed by poorly trained workers; institutions were a place of last resort. Physicians received a limited education through proprietary schools or simple apprenticeship. Medical care was difficult to secure, although public dispensaries (similar to outpatient clinics) and private charitable efforts attempted to address gaps in the availability of sickness services, especially for the urban poor and working classes. Environmental conditions in urban neighborhoods, including inadequate housing and sanitation, were additional risks to health. Table 2-1 presents milestones of public health efforts that occurred during the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries.

TABLE 2-1

MILESTONES IN THE HISTORY OF PUBLIC HEALTH AND COMMUNITY HEALTH NURSING: 1600-1865

| YEAR | MILESTONE |

| 1601 | Elizabethan Poor Law written |

| 1751 | Pennsylvania House founded in Philadelphia |

| 1789 | Baltimore Health Department established |

| 1798 | Marine Hospital Service established; later became Public Health Service |

| 1812 | Sisters of Mercy established in Dublin, Ireland, where nuns visited the poor |

| 1813 | Ladies’ Benevolent Society of Charleston, South Carolina, founded |

| 1836 | Lutheran deaconesses provide home visits in Kaiserwerth, Germany |

| 1851 | Florence Nightingale visits Kaiserwerth for 3 months of nurse training |

| 1855 | Quarantine Board established in New Orleans; beginning of tuberculosis campaign in the United States |

| 1859 | District nursing established in Liverpool, England, by William Rathbone |

| 1860 | Florence Nightingale Training School for Nurses established at St. Thomas Hospital in London, England |

| 1864 | Red Cross established in the United States |

The federal government’s early efforts for public health aimed to secure America’s maritime trade and major coastal cities by providing health care for merchant seamen and by protecting seacoast cities from epidemics. The Public Health Service, still the most important federal public health agency in the twenty-first century, was established in 1798 as the Marine Hospital Service. The first Marine Hospital opened in Norfolk, Virginia, in 1800. Additional legislation to establish quarantine regulations for seamen and immigrants was passed in 1878.

During the early 1800s, experiments in providing nursing care at home focused on moral improvement and less on illness intervention. The Ladies’ Benevolent Society of Charleston, South Carolina, provided charitable assistance to the poor and sick beginning in 1813. In Philadelphia, lay nurses after a brief training program cared for postpartum women and newborns in their homes. In Cincinnati, Ohio, the Roman Catholic Sisters of Charity began a visiting nurse service in 1854 (Rodabaugh and Rodabaugh, 1951). Although these early programs provided services at the local level, they were not adopted elsewhere, and their influence on later public health nursing is unclear.

During the mid-nineteenth century, national interest increased in addressing public health problems and improving urban living conditions. New responsibilities for urban boards of health reflected changing ideas of public health, as the boards began to address communicable diseases and environmental hazards. Soon after it was founded in 1847, the American Medical Association (AMA) formed a hygiene committee to conduct sanitary surveys and to develop a system to collect vital statistics. The Shattuck Report, published in 1850 by the Massachusetts Sanitary Commission, called for major innovations: the establishment of a state health department and local health boards in every town; sanitary surveys and collection of vital statistics; environmental sanitation; food, drug, and communicable disease control; well-child care; health education; tobacco and alcohol control; town planning; and the teaching of preventive medicine in medical schools (Kalisch and Kalisch, 1995). However, these recommendations were not implemented in Massachusetts until 1869, and in other states much later.

In some areas, charitable organizations addressed the gap between known communicable disease epidemics and the lack of local government resources. For example, the Howard Association of New Orleans, Louisiana, responded to periodic yellow fever epidemics between 1837 and 1878 by providing physicians, lay nurses, and medicine. The Association established infirmaries and used sophisticated outreach strategies to locate cases (Hanggi-Myers, 1995).

Nightingale and the Origins of Trained Nursing

The origins of professional nursing are found in the work of Florence Nightingale in nineteenth-century Europe. With tremendous advances in transportation, communication, and other forms of technology, the Industrial Revolution led to deep social upheaval. Even with the advancement of science, medicine, and technology in the two previous centuries, nineteenth-century public health measures continued to be very basic. Organization and management of cities improved slowly, and many areas lacked systems of sewage disposal and depended on private enterprise for water supply. Previous caregiving structures, which relied on the assistance of family, neighbors, and friends, became inadequate in the early nineteenth century because of human migration, urbanization, and changing demand. During this period, a few groups of Roman Catholic and Protestant women provided nursing care for the sick, poor, and neglected in institutions and sometimes in the home. For example, Mary Aikenhead, also known by her religious name Sister Mary Augustine, organized the Irish Sisters of Charity in Dublin (Ireland) in 1815. These sisters visited the poor at home and established hospitals and schools (Kalisch and Kalisch, 1995).

In nineteenth-century England, the Elizabethan Poor Law continued to guarantee medical care for all. This minimal care, provided most often in almshouses supported by local government, sought as much to regulate where the poor could live as to provide care during illness. Many women who performed nursing functions in almshouses and early hospitals in Great Britain were poorly educated, untrained, and often undependable. As the practice of medicine became more complex in the mid-1800s, hospital work required skilled caregivers. Physicians and hospital administrators sought to advance the practice of nursing. Early experiments yielded some improvement in care, but Florence Nightingale’s efforts were revolutionary.

Florence Nightingale’s vision of trained nurses and her model of nursing education influenced the development of professional nursing and, indirectly, public health nursing in the United States. In 1850 and 1851, Nightingale had carefully studied nursing “system and method” by visiting Pastor Theodor Fliedner at his School for Deaconesses in Kaiserwerth, Germany. Pastor Fliedner also built on the work of others, including Mennonite deaconesses in Holland who were engaged in parish work for the poor and the sick, and Elizabeth Fry, the English prison reformer. Thus mid-nineteenth century efforts to reform the practice of nursing drew on a variety of interacting innovations across Europe.

The Kaiserwerth Lutheran deaconesses incorporated care of the sick in the hospital with client care in their homes, and their system of district nursing spread to other German cities. American requests for the deaconesses to respond to epidemics of typhus and cholera in Pittsburgh provided only temporary assistance since local women were uninterested in the work. The early efforts of the Lutheran deaconesses in the United States ultimately focused on developing systems of institutional care (Nutting and Dock, 1935).

Nightingale soon found a way to implement her ideas about nursing. During the Crimean War (1854–1856) between the alliance of England and France against Russia, the British military established hospitals for sick and wounded soldiers at Scutari (in modern Turkey). The care of the sick and wounded soldiers was severely deficient, with cramped quarters, poor sanitation, lice and rats, insufficient food, and inadequate medical supplies (Kalisch and Kalisch, 1995; Palmer, 1983). When the British public demanded improved conditions, Nightingale sought and received an appointment to address the chaos. Because of her wealth, social and political connections, and knowledge of hospitals, the British government sent her to Asia Minor with 40 ladies, 117 hired nurses, and 15 paid servants.

In Scutari, Nightingale progressively improved soldiers’ health outcomes using a population-based approach that strengthened environmental conditions and nursing care. Using simple epidemiological measures, she documented a decreased mortality rate from 415 per 1000 at the beginning of the war to 11.5 per 1000 at the end (Cohen, 1984; Palmer, 1983). Paralleling Nightingale’s efforts in Scutari, public health nurses typically identify health care needs that affect the entire population, mobilize resources, and organize themselves and the community to meet these needs.

Nightingale’s fame was established even before she returned to England in 1856 after the Crimean War. She then organized hospital nursing practice and established hospital-based nursing education to replace the untrained lay nurses with Nightingale nurses. Nightingale also emphasized public health nursing: “The health of the unity is the health of the community. Unless you have the health of the unity, there is no community health” (Nightingale, 1894, p. 455). She differentiated “sick nursing” from “health nursing.” The latter emphasized that nurses should strive to promote health and prevent illness. Nightingale (1946, p. v) wrote that nurses’ task is to “put the constitution in such a state as that it will have no disease, or that it can recover from disease.” Proper nutrition, rest, sanitation, and hygiene were necessary for health. Nurses continue to focus on the vital role of health promotion, disease prevention, and environment in their practice with individuals, families, and communities.

Nightingale’s contemporary and friend, British philanthropist William Rathbone, founded the first district nursing association in Liverpool, England. Rathbone’s wife had received outstanding nursing care from a Nightingale-trained nurse during her terminal illness at home. He wanted to offer similar care to relieve the suffering of poor persons unable to afford private nurses. With Rathbone’s advocacy and economic support between 1859 and 1862, the Liverpool Relief Society divided the city into nursing districts and assigned a committee of “friendly visitors” to each district to provide health care to needy people (Kalisch and Kalisch, 1995). Building on the Liverpool experience, Rathbone and Nightingale recommended steps to provide nursing in the home, and district nursing was organized throughout England. Florence Sarah Lees Craven shaped the profession through her book A Guide to District Nursing, which recommended, for example, that nursing care during the illness of one family member provided the nurse with influence to improve the health status of the whole family (Craven, 1889).

America Needs Trained Nurses

As urbanization increased during America’s Industrial Revolution, the number of jobs for women rapidly increased. Educated women became elementary school teachers, secretaries, or saleswomen. Less-educated women worked in factories of all kinds. The idea of becoming a trained nurse increased in popularity as Nightingale’s successes became known across the United States. During the 1870s, the first nursing schools based on the Nightingale model opened in the United States.

Trained nurse graduates of the early schools for nurses in the United States usually worked in private duty nursing or held the few positions as hospital administrators or instructors. Private duty nurses might live with families of clients receiving care, to be available 24 hours a day. Although the trained nurse’s role in improving American hospitals was very clear, the cost of private duty nursing care for the sick at home was prohibitive for all but the wealthy.

The care of the sick poor at home was made economical by having home-visiting nurses attend several families in a day rather than attend only one client as the private duty nurse did. In 1877 the Women’s Board of the New York City Mission hired Frances Root, a graduate of Bellevue Hospital’s first nursing class, to visit sick poor persons to provide nursing care and religious instruction (Bullough and Bullough, 1964). In 1878 the Ethical Culture Society of New York hired four nurses to work in dispensaries, a type of community-based clinic. In the next few years, visiting nurse associations (VNAs) were established in Buffalo, New York (1885), Philadelphia (1886), and Boston (1886). Wealthy people interested in charitable activities funded both settlement houses and VNAs. Upper-class women, freed of some of the social restrictions that had previously limited their public life, became interested in the charitable work of creating, supporting, and supervising the new visiting nurses. Public health nursing in the United States began with organizing to meet urban health care needs, especially for the disadvantaged.

The public was interested in limiting disease among all classes of people not only for religious reasons as a form of charity, but also because the middle and upper classes feared the impact of communicable diseases believed to originate in the large communities of new European immigrants. In New York City in the 1890s, about 2.3 million people lived in 90,000 tenement houses. Deplorable environmental conditions for immigrants in urban tenement houses and sweatshops were common across the northeastern United States and upper Midwest. “Slum dwellers were ravaged by epidemics of typhus, scarlet fever, smallpox, and typhoid fever, and many of them died or developed tuberculosis” (Kalisch and Kalisch, 1995, p. 172). From the beginning, nursing practice in the community included teaching and prevention (Figure 2-1). Nursing interventions, improved sanitation, economic improvements, and better nutrition were credited with reducing the incidence of acute communicable disease by 1910.

New scientific explanations of communicable disease suggested that preventive education would reduce illness. The visiting nurse became the key to communicating the prevention campaign, through home visits and well-baby clinics. Visiting nurses worked with physicians, gave selected treatments, and kept temperature and pulse records. Visiting nurses emphasized education of family members in the care of the sick and in personal and environmental prevention measures, such as hygiene and good nutrition (Figure 2-2). Many early visiting nurse agencies employed only one nurse, who was supervised by members of the agency board, usually composed of wealthy or socially prominent ladies who were not nurses. These ladies were critically important to the success of visiting nursing through their efforts to open new agencies, financially support existing agencies, and render the services socially acceptable. The work of both visiting nurses and their lady supporters reflected changing societal roles for women as it became more acceptable for women to be active in public arenas than it had been earlier in the nineteenth century.

For example, in 1886 two Boston women approached the Women’s Education Association to seek local support for district nursing. To increase the likelihood of financial support, they used the term instructive district nursing to emphasize the relationship of nursing to health education. The Boston Dispensary provided support in the form of free outpatient medical care. In 1886 the first district nurse was hired, and in 1888 the Instructive District Nursing Association became incorporated as an independent voluntary agency. Sick poor persons, who paid no fees, were cared for under the direction of a trained physician (Brainard, 1922).

Other nurses established settlement houses—neighborhood centers that became hubs for health care, education, and social welfare programs. For example, in 1893 Lillian Wald and Mary Brewster, both trained nurses, began visiting the poor on New York’s Lower East Side. The nurses’ settlement they established became the Henry Street Settlement and later the Visiting Nurse Service of New York City. By 1905 the public health nurses had provided almost 48,000 visits to more than 5000 clients (Kalisch and Kalisch, 1995). Lillian Wald emerged as the established leader of public health nursing during its early decades (Box 2-1; Figure 2-3). Other settlement houses influenced the growth of community nursing including the Richmond (Virginia) Nurses’ Settlement, which became the Instructive Visiting Nurse Association; the Nurses’ Settlement in Orange, New Jersey; and the College Settlement in Los Angeles, California.

School Nursing in America

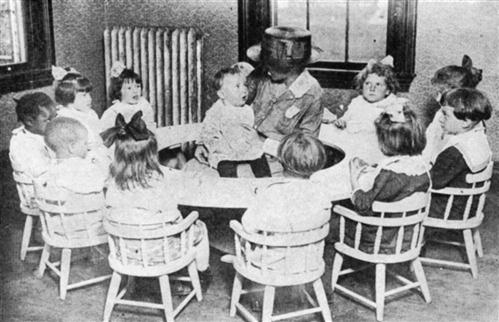

In New York City in 1902, more than 20% of children might be absent from school on a single day. The children suffered from the common conditions of pediculosis, ringworm, scabies, inflamed eyes, discharging ears, and infected wounds. Physicians began to make limited inspections of school students in 1897, and they focused on excluding infectious children from school rather than on providing or obtaining medical treatment to enable children to return to school. Familiar with this community-wide problem from her work with the Henry Street Nurses’ Settlement, Wald sought to place nurses in the schools and gained consent from the city’s health commissioner and the Board of Education for a 1-month demonstration project.

Lina Rogers, a Henry Street Settlement resident, became the first school nurse. She worked with the children in New York City schools and made home visits to instruct parents and to follow up on children excluded or otherwise absent from school. The school nurses found that “many children were absent for lack of shoes or clothing, because of malnourishment, or because they were serving their families as babysitters” (Hawkins, Hayes, and Corliss, 1994, p. 417). The school nurse experiment made such a significant and positive impact that it became permanent, with 12 more nurses appointed 1 month later. School nursing was soon implemented in Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, and San Francisco.

The Profession Comes of Age

Established by the Cleveland Visiting Nurse Association in 1909, the Visiting Nurse Quarterly initiated a professional communication medium for clinical and organizational concerns. In 1911 a joint committee of existing nurse organizations convened, under the leadership of Wald and Mary Gardner, to standardize nursing services outside the hospital. Recommending formation of a new organization to address public health nursing concerns, 800 agencies involved in public health nursing activities were invited to send delegates to an organizational meeting in Chicago in June 1912. After a heated debate on its name and purpose, the delegates established the National Organization for Public Health Nursing (NOPHN) and chose Wald as its first president (Dock, 1922). Unlike other professional nursing organizations, the NOPHN membership included both nurses and their lay supporters. The NOPHN sought “to improve the educational and services standards of the public health nurse, and promote public understanding of and respect for her work” (Rosen, 1958, p. 381). With greater administrative resources than any of the other national nursing organizations existing at that time, the NOPHN was soon the dominant force in public health nursing (Roberts, 1955).

The NOPHN sought to standardize public health nursing education. Visiting nurse agencies found that graduates of the hospital schools were unprepared for home visiting. It became apparent that the basic curriculum of many schools of nursing was insufficient. Because diploma schools of nursing emphasized hospital care of clients, public health nurses would require additional education to provide services to the sick at home and to design population-focused programs. In 1914, in affiliation with the Henry Street Settlement, Mary Adelaide Nutting began the first post-training-school course in public health nursing at Teachers College in New York City (Deloughery, 1977). The American Red Cross provided scholarships for graduates of nursing schools to attend the public health nursing course. Its success encouraged development of other programs, using curricula that might seem familiar to today’s nurses. During the 1920s and 1930s, many newly hired public health nurses had to verify completion or promptly enroll in a certificate program in public health nursing. Others took leave for a year to travel to an urban center to obtain this further education. Correspondence courses (distance education) were even acceptable in some areas, for example, for public health nurses in upstate New York.

Public health nurses were also active in the American Public Health Association (APHA), which was established in 1872 to facilitate interprofessional efforts and promote the “practical application of public hygiene” (Scutchfield and Keck, 1997, p. 12). The APHA targeted reform efforts toward contemporary public health issues, including sewage and garbage disposal, occupational injuries, and sexually transmitted diseases. In 1923 the Public Health Nursing Section was formed within the APHA to provide nurses with a forum to discuss their concerns and strategies within the larger context of the major public health organization. The Section continues to serve as a focus of leadership and policy development for public health nursing.

Public Health Nursing in Official Health Agencies and in World War I

Public health nursing in voluntary agencies and through the Red Cross grew more quickly than public health nursing sponsored by state, local, and national government. In the late 1800s, local health departments were formed in urban areas to target environmental hazards associated with crowded living conditions and dirty streets, and to regulate public baths, slaughterhouses, and pigsties (Pickett and Hanlon, 1990). By 1900, 38 states had established state health departments, following the lead of Massachusetts in 1869; however, these early state boards of health had limited impact. Only three states—Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Florida—annually spent more than 2 cents per capita for public health services (Scutchfield and Keck, 1997).

The federal role in public health gradually expanded. In 1912 the federal government redefined the role of the U.S. Public Health Service, empowering it to “investigate the causes and spread of diseases and the pollution and sanitation of navigable streams and lakes” (Scutchfield and Keck, 1997, p. 15). The NOPHN loaned a nurse to the U.S. Public Health Service during World War I to establish a public health nursing program for military outposts. This led to the first federal government sponsorship of nurses (Shyrock, 1959; Wilner, Walkey, and O’Neill, 1978).

During the 1910s, public health organizations began to target infectious and parasitic diseases in rural areas. The Rockefeller Sanitary Commission, a philanthropic organization active in hookworm control in the southeastern United States, concluded that concurrent efforts for all phases of public health were necessary to successfully address any individual public health problem (Pickett and Hanlon, 1990). For example, in 1911 efforts to control typhoid fever in Yakima County, Washington, and to improve health status in Guilford County, North Carolina, led to establishment of local health units to serve local populations. Public health nurses were the primary staff members of local health departments. These nurses assumed a leadership role on health care issues through collaboration with local residents, nurses, and other health care providers.

The experience of Orange County, California, during the 1920s and 1930s illustrates the role of the public health nurse in these new local health departments. Following the efforts of a private physician, social welfare agencies, and a Red Cross nurse, the county board created the public health nurse’s position, which began in 1922. Presented with a shining new Model T car sporting the bright orange seal of the county, the nurse focused on the serious communicable disease problems of diphtheria and scarlet fever. Typhoid became epidemic when a drainage pipe overflowed into a well, infecting those who drank the water and those who drank raw milk from an infected dairy. Almost 3000 residents were immunized against typhoid. Weekly well-baby conferences provided an opportunity for mothers to learn about care of their infants, and the infants were weighed and given communicable disease immunizations. Children with orthopedic disorders and other disabilities were identified and referred for medical care in Los Angeles. At the end of a successful first year of public health nursing work, the Rockefeller Foundation and the California Health Department recognized the favorable outcomes and provided funding for more public health professionals.

The personnel needs of World War I in Europe depleted the ranks of public health nurses, even as the NOPHN identified a need for second and third lines of defense within the United States. Jane Delano of the Red Cross (which was sending 100 nurses a day to the war) agreed that despite the sacrifice, the greatest patriotic duty of public health nurses was to stay at home. In 1918 the worldwide influenza pandemic swept the United States from the Atlantic coast to the Pacific coast within 3 weeks and was met by a coalition of the NOPHN and the Red Cross. Houses, churches, and social halls were turned into hospitals for the immense numbers of sick and dying. Some of the nurse volunteers died of influenza as well (Shyrock, 1959; Wilner, Walkey, and O’Neill, 1978).

Paying the Bill for Public Health Nurses

Inadequate funding was the major obstacle to extending nursing services in the community. Most early VNAs sought charitable contributions from wealthy and middle-class supporters. Even poor families were encouraged to pay a small fee for nursing services, reflecting social welfare concerns against promoting economic dependency by providing charity. In 1909, as a result of Wald’s collaboration with Dr. Lee Frankel, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company began a cooperative program with visiting nurse organizations that expanded availability of public health nursing services. The nurses assessed illness, taught health practices, and collected data from policyholders. By 1912, 589 Metropolitan Life nursing centers provided care through existing agencies or through visiting nurses hired directly by the company. In 1918 Metropolitan Life calculated an average decline of 7% in the mortality rate of policyholders and almost a 20% decline in the mortality rate of policyholders’ children under age 3. The insurance company attributed this improvement and their reduced costs to the work of visiting nurses. Voluntary health insurance was still decades in the future; public and professional efforts to secure compulsory health insurance seemed promising in 1916 but had evaporated by the end of World War I.

Nursing efforts to influence public policy bridged World War I and included advocacy for the Children’s Bureau and the Sheppard-Towner Program. Responding to lengthy advocacy by Wald and other nurse leaders, the Children’s Bureau was established in 1912 to address national problems of maternal and child welfare. Children’s Bureau experts conducted extensive scientific research on the effects of income, housing, employment, and other factors on infant and maternal mortality. Their research led to federal child labor laws and the 1919 White House Conference on Child Health.

Problems of maternal and child morbidity and mortality spurred the passage of the Maternity and Infancy Act (often called the Sheppard-Towner Act) in 1921. This act provided federal matching funds to establish maternal and child health divisions in state health departments. Education during home visits by public health nurses stressed promoting the health of mother and child as well as seeking prompt medical care during pregnancy. Although credited with saving many lives, the Sheppard-Towner Program ended in 1929 in response to charges by the AMA and others that the legislation gave too much power to the federal government and too closely resembled socialized medicine (Pickett and Hanlon, 1990).

Some nursing innovations were the result of individual commitment and private financial support. In 1925 Mary Breckinridge established the Frontier Nursing Service (FNS) to emulate systems of care used in the Highlands and islands of Scotland (Box 2-2; Figure 2-4). The unique pioneering spirit of the FNS influenced development of public health programs geared toward improving the health care of the rural and often inaccessible populations in the Appalachian region of southeastern Kentucky (Browne, 1966; Tirpak, 1975). Breckinridge introduced the first nurse-midwives into the United States when she deployed FNS nurses trained in nursing, public health, and midwifery. Their efforts led to reduced pregnancy complications and maternal mortality, and to one-third fewer stillbirths and infant deaths in an area of 700 square miles (Kalisch and Kalisch, 1995). Today the FNS continues to provide comprehensive health and nursing services to the people of that area and sponsors the Frontier School of Midwifery and Family Nursing.