Health Teaching

Gail L. Heiss

Focus Questions

What is the distinction between patient education and health education?

How does the community/public health nurse identify health education needs?

What impact do the community environment and culture have on these learning needs?

What teaching strategies should the nurse use with the identified target group for education?

How will the nurse know whether the teaching strategies have been effective?

What community resources are available to enhance health education?

Key Terms

Andragogy

Behavioral objectives

Emotional readiness

Experiential readiness

Health education

Health literacy

Low literacy

Outcome evaluation

Patient education

PRECEDE model

Process evaluation

Self-efficacy

SMOG

Teaching–learning process

The concept and practice of teaching clients in the community have been evolving since the days of Lillian Wald and continue to change with the profession of nursing. Today, individuals and families expect to be more involved in decisions about health care, and they want to learn about illness prevention and behavioral changes required to maintain health and an active lifestyle.

This chapter provides the community/public health nurse with the concepts and tools needed to develop and implement community health education programs. With the opportunity for health education, members of the community will have the resources and support to strive for personal, family, and community health.

Health-teaching process

Definitions

Patient Education

Differentiating between patient education and health education is helpful. The term patient education is normally used to describe a series of planned teaching–learning activities designed for individuals, families, or groups who have an identified alteration in health. The nurse uses a systematic process to assess patient learning needs that relate to the health problem and then implements the teaching plan to accomplish changes in attitude or behavior (Redman, 1997).

Health Education

Health education focuses on health promotion and disease prevention. The role of the community/public health nurse includes educating and empowering people to avoid disease, to make lifestyle changes, and to improve health for themselves, their families, the environment, and their community. The difference between patient education and health education is that health education is directed toward individuals or populations who are not experiencing an acute alteration in health. Community assessment identifies individuals, families, groups, and populations who would benefit from additional information on healthy behaviors and healthy lifestyles. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services monitors the effectiveness of health education as it relates to the population of the United States and publishes this information regularly in the Healthy People reports. Data is collected, reviewed and published at the Healthy People website (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2010a). See the Healthy People 2020 box.

Policies

Quad Council of Public Health Nursing Organizations

The Quad Council of Public Health Nursing Organizations collaborated to produce Public Health Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2007), which outlines health education and the provision of teaching–learning opportunities as a distinct intervention by the community/public health nurse. Health education interventions may be conducted with individuals, families, and groups in health care institutions, homes, schools, communities, and the workplace. Health education nursing interventions are often implemented in partnership with community members, community leaders, and other health care providers.

Financial Reimbursement

Nurses quite possibly have the greatest opportunity to implement educational programs because of the extensive amount of time they spend with individuals and families in the community. Currently, the structure of insurance companies in the United States is based on reimbursement for illness care rather than for wellness promotion. Reimbursement is available for physician-ordered education relating to existing illness such as diabetes management. A disappointing note is that in many instances, no method exists for direct reimbursement of the nurse who provides health promotion education to the community. However, current practices in primary care settings provide opportunities for nurses to combine health-promotion education with required health screenings to detect or prevent disease.

Community educational programs are sometimes offered to the community for a fee. Individuals who value self-care and health will often pay out of pocket for educational programs such as weight management or childbirth education. In this case, the nurse does receive payment for teaching and preparation time. Unfortunately, people who cannot afford to pay for educational services are excluded.

Some nurses provide health education as a part of their jobs, such as nurses working for managed care organizations, and are reimbursed with a salary. This group may also include occupational health nurses, school nurses, and nurses in the traditional public health setting. In addition to planning group education, public health nurses often have a caseload of families and individuals who need direct care and home visits. Careful time management is required for planning and implementing health education.

Expanding Opportunities

In today’s health care delivery system, the community/public health nurse has unique opportunities to shape the future. A growing emphasis has been placed on the allocation of resources to consumer health education for health promotion and disease prevention, and nursing opportunities outside of the traditional hospital roles. Nurse entrepreneurs can use the public demand for health education to develop and market educational programs that meet population needs. Nurses who work in community health agencies can use the health education trends to expand their job descriptions and advance professionally. Nurses can also work politically to influence public policy regarding development and funding of health education programs.

Health promotion through health education and utilization of resources is also of interest to the nurse in the occupational setting. The occupational nurse can work with distinct groups to assess health needs and provide education on topics such as stress management, smoking cessation, nutrition, exercise, and weight management. The nurse is also an important link between employees and community resources.

Research evidence: what works in client health education?

Research on health education has been extensive. Some of the most prominent public health research regarding individuals’ adherence to health promotion activities was initiated in the 1950s by Becker, Hochbaum, Kegeles, and Rosenstock (see Rosenstock, 1974; see also Chapter 18). According to the research of these authors, participation in prevention activities such as educational programs will influence health behaviors.

Multiple Tools and Methods

No doubt, health education works, and actual changes in behavior and attitudes occur after health education interventions. Health education includes a variety of strategies, such as lecturing, storytelling, modeling, providing printed or audiovisual materials, and use of games and interactive experiences. Also available are technology-based educational opportunities including telehealth conferencing and counseling of individuals on how to identify reliable health-related Internet sites. All of these methods are effective in increasing knowledge or skill level. Using multiple methods of teaching is more effective because individuals learn in different ways.

Continued nursing research is needed on the use of web-based techniques and other technologies for instruction and their effectiveness for diverse populations. An interesting pilot study comparing the effectiveness of web-based instruction and written instruction for rural mothers on communication with their adolescent children regarding sex found that both methods of education were effective. The low-income women who had little or no previous experience using computers were able to effectively learn using web-based materials (Cox et al., 2009). Cost-saving efforts in health care delivery are a priority. An article on the effectiveness of videoconferencing as a cost-effective method of providing patient education (Winters & Winters, 2007) indicated that the use of technology is both cost-effective and leads to favorable patient health outcomes.

Individualization and the Adult Learner

Individual characteristics such as age, social status, cultural attributes, and educational level influence teaching effectiveness and long-term health behaviors. Standard lecture methods that do not consider these or other individual differences may be ineffective in teaching health promotion and self-care. Therefore, the educational program should be individualized to meet the learner’s needs.

The nurse needs to assess the learner’s teaching–learning style. Clients may prefer to learn by reading, watching videotapes, viewing a demonstration, participating in groups, or listening and then attempting new behaviors. Matching learning style and the nurse’s ability to meet the learner’s style will affect how well people learn. Assessment of andragogy, or the teaching–learning style, is most important in the process of teaching adults.

Knowles (1980) identified some basic tenets that are consistently recognized in adult education; adults learn best when they are actively involved, when the information is repeated, when prompt feedback is received, and when the adult attaches importance to the topic (Table 20-1). Learners remember best what is taught first, so the use of focusing activities early in the education session is important. Other strategies that are useful when teaching adults include the following:

• Relate the content to life experiences

• Focus on real-world problems

• Relate the activities to learner-focused goals

• Listen to and respect the opinions of the learner

• Encourage the learner to share resources with you and other learners

Table 20-1

Characteristics of Adult Learners

| Children (Pedagogy) | Adults (Andragogy) |

| Others decide what is important | Decide for themselves what they want to learn |

| Accept information as you teach it | Validate and evaluate information based on life experiences and beliefs |

| Have limited past experience | Have a lifetime of experience |

| Expect to use information in the future | Want the information to be immediately useful |

| Focus on the facts | Focus on application of the facts |

| Teacher is the authority | Teacher and learners collaborate |

| Teacher plans the lesson | Planning of content is shared |

| Passive recipient of information | Active participant in the learning process |

Data from Knowles, M. S. (1980). The modern process of adult education: From pedagogy to andragogy. New York: Cambridge Books.

Support Systems

The presence of a peer group can enhance learning by providing encouragement to learners as they try new behaviors and by giving positive reinforcement when goals are met. In addition, teaching a supportive family instead of just one family member is more effective in achieving learning objectives and modifying behavior. For groups of community learners, special efforts to include culturally appropriate information and the use of culturally sensitive materials may enhance participation and learning. For example, provision of culturally appropriate instruction, support group interaction, and behavioral contracting were methods used to enhance adherence to a walking program among postmenopausal African American women (Williams et al., 2005).

Nursing assessment of health-related learning needs

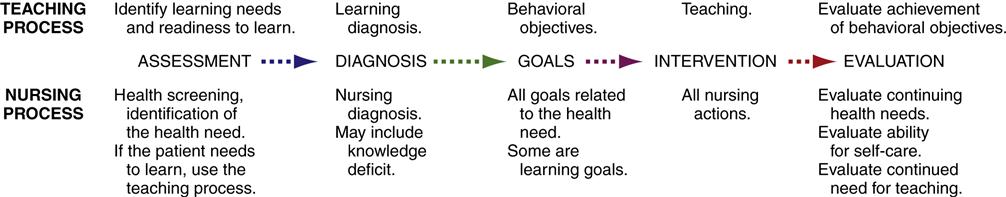

The development of content, strategies for teaching, and evaluation of the effectiveness of the health education program should be carried out in a systematic manner to achieve the most effective results. This systematic method is the teaching–learning process. The teaching–learning process parallels the nursing process (Figure 20-1). The nurse will use both the nursing process and the teaching–learning process to intervene for community health promotion.

Assessment of Community Learning Needs

To create a health education program for a community, both the needs of the community and the learning needs of the individual participants should be assessed. Assessment of the community is based on epidemiological and demographic data, observations made by health care personnel in the community, results of surveys, and conversations with community members (see Chapter 15). The need for community education can be assessed using the four classifications of educational needs as originally described by Atwood and Ellis (1971):

• A real need is one that is based on a deficiency that actually exists.

• An educational need is one that can be met by a learning experience.

The combined community assessment and educational needs assessment provide the impetus for planning a health education program.

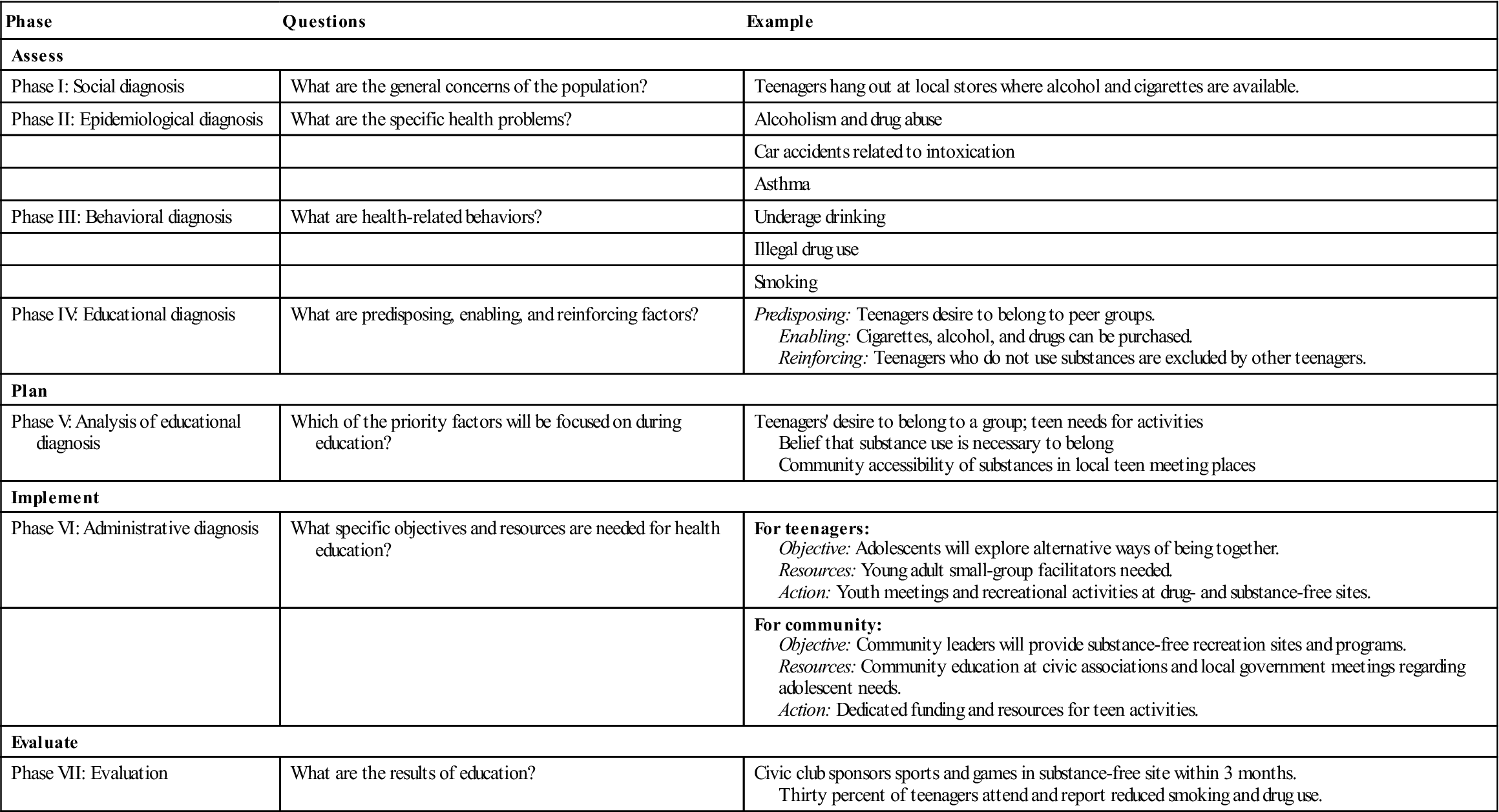

A model that combines community assessment and educational planning is the PRECEDE model. PRECEDE is an acronym for predisposing, reinforcing, and enabling causes in educational diagnosis and evaluation (Green & Kreuter, 1991). Predisposing factors are characteristics of the learner; these include knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions that motivate health-related behavior. Enabling factors are environmental resources and learner skills that facilitate or hinder attainment of health behaviors. Reinforcing factors are the actual or expected rewards and feedback a learner receives after engaging in a health behavior. These three types of factors influence health-related behavior, which, in turn, contributes to the presence or absence of health problems that are linked with quality of life.

The phases of the PRECEDE model are similar to the steps of the nursing process. Phases 1 through 4 involve assessment, phase 5 is priority setting and planning, phase 6 is implementation, and phase 7 is evaluation (Table 20-2).

Table 20-2

Phases of the Precede Model: Sample Community Educational Plan

| Phase | Questions | Example |

| Assess | ||

| Phase I: Social diagnosis | What are the general concerns of the population? | Teenagers hang out at local stores where alcohol and cigarettes are available. |

| Phase II: Epidemiological diagnosis | What are the specific health problems? | Alcoholism and drug abuse |

| Car accidents related to intoxication | ||

| Asthma | ||

| Phase III: Behavioral diagnosis | What are health-related behaviors? | Underage drinking |

| Illegal drug use | ||

| Smoking | ||

| Phase IV: Educational diagnosis | What are predisposing, enabling, and reinforcing factors? | Predisposing: Teenagers desire to belong to peer groups. Enabling: Cigarettes, alcohol, and drugs can be purchased. Reinforcing: Teenagers who do not use substances are excluded by other teenagers. |

| Plan | ||

| Phase V: Analysis of educational diagnosis | Which of the priority factors will be focused on during education? | Teenagers’ desire to belong to a group; teen needs for activities Belief that substance use is necessary to belong Community accessibility of substances in local teen meeting places |

| Implement | ||

| Phase VI: Administrative diagnosis | What specific objectives and resources are needed for health education? | For teenagers: Objective: Adolescents will explore alternative ways of being together. Resources: Young adult small-group facilitators needed. Action: Youth meetings and recreational activities at drug- and substance-free sites. |

| For community: Objective: Community leaders will provide substance-free recreation sites and programs. Resources: Community education at civic associations and local government meetings regarding adolescent needs. Action: Dedicated funding and resources for teen activities. | ||

| Evaluate | ||

| Phase VII: Evaluation | What are the results of education? | Civic club sponsors sports and games in substance-free site within 3 months. Thirty percent of teenagers attend and report reduced smoking and drug use. |

PRECEDE, Predisposing, reinforcing, and enabling causes in educational diagnosis and evaluation.

Data from Green, L., & Kreuter, M. (1991). Health promotion planning: An educational and environmental approach. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing.

Most of the seven phases of the PRECEDE model begin with a diagnosis. In each phase, the health educator looks to the preceding cause and factors that influence the diagnosis. The educator answers why a situation is occurring before planning the educational intervention. Analysis of the causes of the health problem helps eliminate the risk of planning ineffective interventions based on guesswork.

Assessment of the Learner

Assessment of the learner is essential to planning the educational program. Assessment of the learner also helps facilitate the learner’s acceptance and use of the information being offered. Within the community, the learner may be an individual, family, or group. Initial assessment of the learner is often referred to as assessment of the learner’s readiness to learn. In an early publication, which continues to have relevance, Redman (1984) described two aspects of readiness: emotional and experiential.

Emotional Readiness

Emotional readiness is the learner’s motivation, or the willingness to put forth the effort needed to learn. Motivation to learn is based on attitudes and beliefs about health-related behaviors.

Motivation may be internally or externally reinforced. Internal motivation is more self-directive and longer lasting and involves satisfaction in health-promoting activities based on the belief that the action is useful or enjoyable. External motivation must be constantly reinforced by rewards or praise. For example, an individual who joins a weight-loss group is more likely to achieve and maintain a weight loss if he or she joins the group to satisfy his or her own need for health, wellness, and self-esteem (internal motivation). If he or she joins the group to receive the rewards of buying new clothes or garnering the praise of others (external motivation), the person is less likely to maintain the weight loss.

Experiential Readiness

Experiential readiness includes the client’s background, skill, and ability to learn (Redman, 1984). Assessment of the client’s background examines cultural factors, the home environment, and socioeconomic status. This background information is useful in describing current health behaviors and the learner’s ability to use education to change behavior.

Client skills and self-perception of skills are part of experiential readiness. A client who is learning to bathe a newborn needs both coordination and the belief that he or she can learn. It is also useful to assess how clients prefer to learn procedures or skills. Based on experience, do clients prefer to try themselves, correcting their own mistakes, or do they prefer to be led through the process step-by-step several times until they feel confident?

Developmental stages of both the individual and the family present another aspect of experiential readiness. Educational content should be developmentally appropriate. For example, a session on the dangers of teenagers’ drinking and driving would have similar content on the dangers of drinking and tips to prevent or resist alcohol use whether delivered to a group of teens or to a group of their parents. However, the material would be presented differently to the two groups.

Finally, in determining experiential readiness, the client’s ability to learn should be assessed. Very pertinent is determining the client’s educational level. Direct questioning related to years of formal education is useful but does not always provide complete and accurate information. For example, although a client may have completed college, if the client did not study medicine or nursing, he or she may not understand complex medical terminology. In addition, reading ability and learning disabilities should be considered (Box 20-1).

Barriers to Learning

Assessment of the learner also requires assessment of barriers to learning. Barriers may be cultural, language, or physical barriers. One of the foundation health measures in Healthy People 2020 is the elimination of health care disparities such as those that may be inherent in health education programs. Inclusion of culturally appropriate teaching materials and a culturally sensitive approach to individual and family education is required. Culturally appropriate teaching materials for diverse groups are available through several resources including the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2011) Healthfinder.gov site (http://www.healthfinder.gov), and the Office of Minority Health (2011) (http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov). The Healthfinder.gov site can be viewed entirely in Spanish and the Office of Minority Health website includes links for numerous population groups including African Americans, American Indians and Alaskan Natives, and Asian Americans. In addition, the community/public health nurse should establish partnerships with leaders of the community. These partners can help the nurse develop understanding of the population(s) and interpret their acceptance (or lack of acceptance) of health recommendations.

Physical barriers are also important in assessing the learner. Some physical barriers are obvious, such as the use of mobility aids, and the nurse will be able to help clients with these difficulties access the learning environment. Less obvious are physical barriers such as vision or hearing problems, brain injury, or learning disabilities. The nurse should make sure that the setting accommodates learners with these problems so that they do not become frustrated with health education. Large-print materials, good lighting, reduction of background noise, and appropriate seating are a few easy modifications that can reduce or eliminate physical barriers to learning.

Working with Groups of Learners

The community/public health nurse frequently implements health education programs with groups of learners. The group may come from within the community to participate in an advertised education program; the group may also be formed as a result of screening and identification of families with health needs (Boxes 20-2 and 20-3).

In a group, background, skills, abilities, and motivation are different for each group member. An assessment of each learner’s readiness to learn before the first group meeting is useful for determining group composition. If performing an individual assessment before the group meeting is not possible, some introductory time during the first meeting might be used to assess readiness to learn and the learners’ needs and motivations for behavioral change. The nurse may want to ask a colleague to record the information about learning needs and abilities so the task of taking notes will not distract from the important task of establishing rapport. An easy technique to use during the first group meeting to assess learners’ needs is a flip chart and markers. Each member of the group may be asked simple questions during introduction time, such as, “What brought you to the meeting today?”, “What would you like to learn?”, or “How do you like to learn new things?” Answers are recorded on the flip chart.

Construction of health education lesson plans

The next step in the teaching–learning process is the construction of the health education lesson plan. In the initial phase of the teaching–learning process, the nurse assesses what the learner wants or needs to be able to accomplish. The next step, creating the lesson plan, begins with statements of the results the nurse wants the learner to achieve. Each statement is a behavioral objective. The result of the education may be a change in attitude, skill, behavior, or knowledge, but it must be stated before the actual teaching begins.

Creating Behavioral Objectives

Behavioral objectives reflect changes in the learner that are observable or measurable. If the behavioral objectives are properly written, they will be useful tools in helping the instructor 1) decide which content and activities will get the learner to the desired outcomes and 2) evaluate the outcome. An important point to remember is that behavioral objectives are statements of what the learner achieves, not statements of the teacher’s activities. A classic resource on the writing of behavioral objectives (Grolund, 1970) identifies the use of behavioral objectives to accomplish the following:

• Provide direction for the teacher and indicate to others the instructional intent

• Guide the selection of course content, teaching strategies, and teaching materials

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree