Global Health

Helen R. Kohler and Frances A. Maurer

Focus Questions

What is the concept of global health?

Why are health disparities an important global concern?

Which countries have higher rates of deaths from malnutrition and infectious diseases?

Which countries are more concerned about chronic health conditions?

What epidemiological transition is occurring?

What features distinguish health care delivery systems?

Which criteria are used to compare the effectiveness of health care delivery systems?

What types of concerns are common to all forms of health care delivery systems?

Key Terms

Alma-Ata conference

Beveridge model

Bismarck model

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Emerging infectious diseases

Epidemiological transition

Global Health Council (GHC)

Globalization of health

Health disparities

Health for All

Intergovernmental organizations

Millennium Development Goals

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO)

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)

U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)

Voluntary organizations

World Bank

World Health Organization (WHO)

Health: a global issue

It is a small world. Even though the population of the world will soon be 7 billion people (United Nations Population Fund, 2011) distributed throughout more than 200 countries worldwide, we are increasingly becoming a global community. Any commodity or condition is only a plane flight away from any other geographical region, and people everywhere are in constant electronic communication. “The explosion of cell phones in the developing world, particularly in Africa” (where the majority of the people have access to a phone), has made expansion of new strategies for better health possible (Bristol, 2009). “Twitter, Facebook and smartphone apps have become the latest tools in the public health and disaster preparedness fields.” Information and warnings about the March 16, 2011, earthquake and tsunami in Japan “were tweeted and texted as they occurred” (Tucker, 2011). Geographical information systems (GIS) are used to map disease outbreaks and available health facilities to identify vulnerable populations most in need of preventive and curative services (University of North Carolina, 2007; Yeoman, 2010).

More people travel, travel is more rapid, and the boundaries between nations are more fluid, and so we need to think of health, illness, and disease from a global perspective. Highly infectious diseases can circle the world rapidly, as the recent severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic and the H1N1 influenza (“flu”) epidemic illustrate (see Chapters 7 and 8). It is almost impossible to isolate a contagious disease within the country of origin. Other countries also face the risk of exposure. No nation can afford to become complacent. For example, the continued spread of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) worldwide was partially the result of complacency. Some countries were slow to recognize the threat of HIV/AIDS, others denied that the threat existed, and still others thought geographical distance from the initial epidemic protected them from the threat.

Countries with highly sophisticated medical systems are not immune to external health risks. They cannot isolate themselves from exposure risks. Developed countries are more equipped to provide highly specialized care than are poorer developing countries. The former have more sophisticated resources to treat diseases and possess more stringent surveillance and protection measures to reduce the risk of disease. However, developed countries cannot guarantee their citizens protection from external disease sources. More than two million people cross-national boundaries daily. It takes only a single traveler with an undetected illness to expose many people, and sometimes many countries, outside his or her native land.

Health disparities among countries

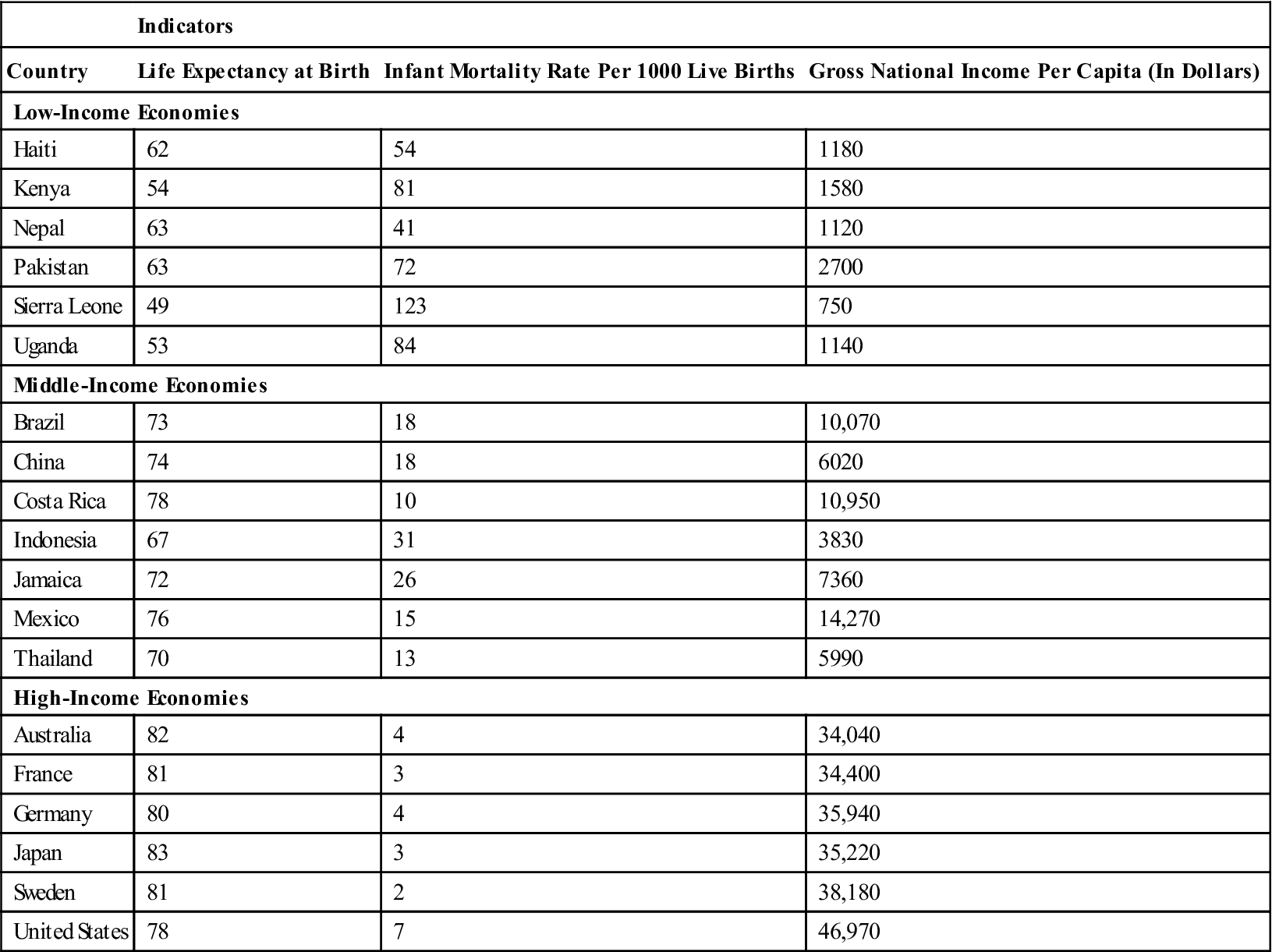

The health status of populations is greatly influenced by income level and therefore varies widely among countries, as shown by the health status indicators in Table 5-1. Developed countries are richer and more economically stable. These countries can provide, in addition to other things, a better standard of health and health care for their citizens. Developed countries include Australia, the United Kingdom, Germany, and the United States, among others. Underdeveloped or developing countries are poorer, often economically unstable, and have less ability to provide health care for their citizens. Social disruptions and wars also affect health in negative ways. Some examples of developing countries include Ethiopia, the Honduras, Vietnam, Malawi, and Rwanda. In very poor countries such as Malawi and Rwanda, approximately 75% of the population was living on less than $1 a day in 2007 (World Health Organization [WHO], 2010a). Somewhere in between are middle-income countries. These are countries that are progressing along the development spectrum but have not achieved the same standard of living as that of developed countries. Brazil, China, Mexico, and Turkey are examples of middle-income countries. These countries tend to provide a standard of health care that is higher than that of poor countries but lower than that of developed countries.

Table 5-1

International Comparison of Health Indicators for Selected Countries: 2008

| Indicators | |||

| Country | Life Expectancy at Birth | Infant Mortality Rate Per 1000 Live Births | Gross National Income Per Capita (In Dollars) |

| Low-Income Economies | |||

| Haiti | 62 | 54 | 1180 |

| Kenya | 54 | 81 | 1580 |

| Nepal | 63 | 41 | 1120 |

| Pakistan | 63 | 72 | 2700 |

| Sierra Leone | 49 | 123 | 750 |

| Uganda | 53 | 84 | 1140 |

| Middle-Income Economies | |||

| Brazil | 73 | 18 | 10,070 |

| China | 74 | 18 | 6020 |

| Costa Rica | 78 | 10 | 10,950 |

| Indonesia | 67 | 31 | 3830 |

| Jamaica | 72 | 26 | 7360 |

| Mexico | 76 | 15 | 14,270 |

| Thailand | 70 | 13 | 5990 |

| High-Income Economies | |||

| Australia | 82 | 4 | 34,040 |

| France | 81 | 3 | 34,400 |

| Germany | 80 | 4 | 35,940 |

| Japan | 83 | 3 | 35,220 |

| Sweden | 81 | 2 | 38,180 |

| United States | 78 | 7 | 46,970 |

Data from World Health Organization (WHO). (2010). World health statistics 2010. Geneva: Author.

The health of the population in developing countries is dramatically impacted by poverty. Poorer countries have higher rates of death, disease, and disability. Children in developing countries suffer from malnutrition and premature death. Infectious diseases such as malaria, meningitis, and cholera, almost nonexistent in developed countries, are rampant in some poorer nations. Life expectancy in these countries is shorter. For example, the life expectancy in Japan is 83 years; in the United States, 78 years; in China, 74 years; and in Zimbabwe, experiencing social unrest and high HIV/AIDS prevalence, just 42 years (WHO, 2010f).

Health disparities, the unequal levels of health among nations, are an ongoing concern of health care professionals and world leaders. At the Alma-Ata conference, a Joint World Health Organization /United Nations Children’s Fund (WHO/UNICEF) International Conference on Primary Health Care held in 1978 in Alma-Ata, USSR (now Almaty, Kazakhstan) and attended by representatives of 143 nations, the WHO renewed its goal of Health for All everywhere. This was a commitment to the social justice of eliminating health disparities (WHO, 1998, 2000). As defined at the Alma-Ata conference, primary health care should encompass the following (WHO, 1978):

• Education about health problems and the means to prevent or control them (country specific)

• Improved food supply and adequate nutrition for the population

• Maternal and child health care

• Immunization against infectious diseases

• Prevention and control of endemic diseases

• Adequate treatment of common diseases and injuries

The Declaration of Alma-Ata serves as a blueprint based on which countries can plan improvements to health services and health status for their citizens (much as the Healthy People 2020 goals serve as a roadmap for improving the health of the U.S. population). The World Health Assembly expects these efforts to be a partnership among the country’s leaders, health infrastructure (organizations), communities, individual citizens, and, to some degree, other countries.

At the United Nations (UN) Millennium Summit in New York City in September 2000 (22 years after the Alma-Ata conference), the largest gathering of world leaders in history, representing 189 nations, adopted the UN Millennium Declaration. The global representatives present committed themselves to giving a very high priority to elimination of worldwide poverty by 2015 (WHO, 2004). The eight specific Millennium Development Goals contained in the Declaration are the following (Jacobsen, 2008, p.283; Uys, 2006):

1. Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

2. Achieve universal primary education

3. Promote gender equality and empower women

6. Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases

7. Ensure environmental sustainability

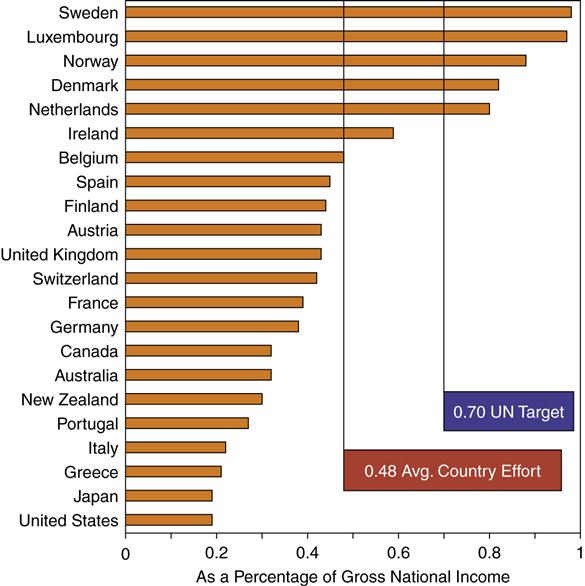

The governments of the 22 wealthiest donor nations in the world agreed to commit 0.7% of their gross domestic product (GDP) by the year 2015 toward the accomplishment of the Millennium Development Goals. Figure 5-1 shows the extent to which these nations have met their commitments 5 years after the summit meeting (UN Millennium Project, 2006; Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2010).

The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and its collaborators in the Disease Control Priorities Project published the “Top 10 Best Buys” of health interventions for developing countries (Eberwine-Villagran, 2007). “Best buys” are interventions for which the money, time, and effort invested have a substantial effect on health and reduce health disparities in poorer countries. Some are relatively simple, whereas others require serious national or international commitment. The 10 interventions are listed in Box 5-1.

It must be remembered that to be more than empty slogans, the Alma-Ata Declaration of Health for All, the UN Millennium Development Goals for reducing global poverty, and the designated Top 10 Health Interventions of the Disease Control Priorities Project require political will and commitment plus predictable and sustained funding.

The concept of globalization of health recognizes that barriers between countries are blurring, that health issues cannot be isolated within one country, that large health disparities among countries are ultimately harmful to everyone, and that health for the world’s population should be the goal of every country. The WHO has made the elimination of health disparities its primary goal (Wagstaff, 2002). Although some progress has been made, much remains to be done. Even though the global strategy of Health for All was endorsed by 143 countries at Alma-Ata in 1978, it remains a statement of aspiration, not a reality (Novelli, 2005). With respect to meeting the Millennium goals, much remains to be done by 2015. Former UN secretary- general Kofi Annan observed that there is still time for achievement, but only “if we break with business as usual” and exert the sustained action required (Uys, 2006). It is yet to be seen how the worldwide recession which began in 2008 will affect the attainment of these goals.

International health organizations

Attempts to improve the level of health worldwide are a multiorganizational effort. Both intergovernmental and voluntary agencies focus on global health problems.

Intergovernmental Organizations

Intergovernmental organizations are agencies in which official representatives of various countries’ governments work together to improve health status. The agency can involve many countries (multilateral agencies) or just two countries (bilateral agencies). The most well-known is the WHO.

World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a multilateral agency involving approximately 193 countries. It was founded to be “the world’s health advocate” more than 50 years ago (WHO, 1998). Although it is associated with the UN, it has its own budget and decision-making processes. Policy decisions and direction are decided by delegates of the member nations at their annual World Health Assembly held in Geneva, Switzerland. The WHO is funded by fees and voluntary contributions from member countries.

The WHO provides both technical support and health care services to member nations, with an emphasis on poorer countries. It directs and coordinates international health projects, collaborates with other organizations and agencies in health care programs, and monitors and reports on worldwide disease conditions, much like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) does for the United States.

The WHO is leading the effort to establish international standards for medications and vaccines. One standard will ensure that the quality and dosage of medications are safe and at therapeutic levels. It also operates thousands of individual country projects, usually in conjunction with the country’s health ministry, the governmental body responsible for health care. Countries receive help with health planning—for example, distribution or establishment of health care services. The WHO helps run immunization programs, build health care infrastructure, and improve sanitation levels.

Pan American Health Organization

The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), established in 1902 as an independent public health organization, now functions as a quasi-independent branch of the WHO. Part of the PAHO’s budget comes from the WHO and from other UN agencies. The PAHO serves as a regional office of the WHO, limited to the Americas, or the western hemisphere. There are 25 member countries.

The primary mission of the PAHO is to strengthen international and local health systems to improve the health and living standards of the population of the Americas. It provides expertise on disease and environmental management, supports research and scholarship efforts, and monitors diseases. The organization has a major emphasis in Latin America, an area of great need. The PAHO has worked hard to provide childhood immunization and other methods of care to reduce infant mortality. For example, the celebration of the ninth Annual Vaccination Week in the Americas (April 23-30, 2011) brought the total number of individuals immunized against vaccine-preventable diseases to over 323 million (PAHO, 2011). Several other WHO regions initiated vaccination weeks during that time, moving toward a global disease prevention effort.

United Nations Children’s Fund

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) (formerly the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund) concentrates its efforts in the area of maternal and child health. It is currently working in 190 countries (UNICEF, 2011a). It is an agency of the UN, from which it receives funding. In the past, UNICEF has concentrated on the control of specific communicable diseases. Although still maintaining that focus, it has expanded into the area of primary prevention. More recent efforts are geared toward ensuring fresh water and safe food supplies and providing health education for mothers, education for girls, and immunization programs aimed at reducing or eliminating vaccine-susceptible communicable diseases.

World Bank

The World Bank was established in 1944 to fight poverty by helping people to help themselves and their environments. It provides resources and shares knowledge through partnerships in the public and private sectors. Examples are providing low-interest loans and grants to developing countries for improvements in education, health, agriculture, and natural resource management.

The World Bank is “not a bank in the common sense,” since it is composed of “two unique development institutions owned by 187 member countries.” It has over 100 offices worldwide, and is headquartered in Washington, DC (World Bank, 2011).

Agency for International Development

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) is an arm of the U.S. State Department. The USAID provides expertise and funding to countries that need economic development. The USAID is an example of a bilateral agency in which one donor, in this case the United States, works with one recipient country. Other governments provide similar services to developing countries. Most of the USAID activities that are publicized are related to agricultural and infrastructure development. In the course of these activities, sanitation and water supplies, essential elements for increasing the level of health in populations, are also improved. In 2007, the USAID was also assisting many countries with activities to combat avian flu, mostly by providing grants and technical assistance (USAID, 2007). In 2009, it procured 42 million poultry avian flu vaccine doses for distribution by the Indonesian Ministry of Health. The USAID also provides millions of bed nets for malaria prevention and hospital equipment worth millions of dollars for the world’s poorest regions (USAID, 2009b). Its continuing work in Afghanistan will be discussed in the section on War and Terrorism below.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USHHS), provides expertise in controlling and preventing disease. Based in Atlanta, Georgia, it directs ongoing health-related programs through the International Health Program Office. The agency is also available for consultation during emergencies such as the 2003 SARS outbreak, the H1N1 flu pandemic of 2009, the cholera epidemic in Haiti in 2010, and the Echerichia coli (E. coli) outbreak in Germany in 2011. In instances of disease outbreaks, experts in the field are dispatched to the country in need, where they consult with the country’s health care professionals and provide equipment and health resources as needed to develop a comprehensive plan for disease control or elimination.

Voluntary Organizations

A wide variety of nongovernmental voluntary organizations assist in the effort to improve worldwide health. These voluntary organizations are frequently referred to as nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). NGOs are not affiliated with a particular government, although some might work in conjunction with a governmental agency on a specific project. Most developed countries have nongovernmental organizations that operate in health-related activities in developing countries.

In the United States, some religious groups operate health-related assistance programs for underdeveloped countries. Protestant denominations and the Catholic Church operate missions that serve selected countries (e.g., countries in Africa, Asia, and South America). The Church Rural Overseas Project, which began as an organization sending food relief to post–World War II (WWII) Europe, now provides worldwide emergency aid, long-term self-help projects, and assistance to refugees from war-torn or famine-plagued countries.

Some examples of religiously affiliated health aid organizations are Lutheran World Relief, Seventh Day Adventist World Service, American Friends Service Committee, and Catholic Relief Services. These groups operate hospitals and clinics as well as schools. Some groups provide health-related education in an effort to increase the number of local health care professionals available to communities. Church organizations provide both permanent and temporary staff for these endeavors. Catholic nuns and priests, Protestant pastors, and other religiously affiliated personnel spend years or even their whole careers in mission work. Some health care professionals volunteer a year of service or do periodic work—for example, 1 month per year for special projects. Some examples of these activities are the following:

• Surgical visits for the repair of cleft lip and palates

• Immunization projects such as measles vaccination

• Water supply projects such as digging wells for a village or community

Global Health Council

The Global Health Council (GHC) is “the world’s largest membership alliance dedicated to saving lives by improving health throughout the world.” Its mission is to provide information and resources needed for successful work toward global health improvement. It serves and represents thousands of public health professionals from more than 103 countries on six continents (Global Health Council, 2011b).

Other Service Agencies

Many organizations are involved in health service to developing countries. Some of these are foundations, privately funded philanthropic organizations, or other types of service agencies. A selection of these organizations is listed in Box 5-2. There are many more voluntary organizations engaged in improving the status of health worldwide.

Health and disease worldwide

There is wide disparity in health status among nations. As a general rule, health status is inversely related to wealth. The poorer the country, the more likely its citizens are to experience preventable diseases and early death. Excessive deaths from communicable and vaccine preventable diseases are still occurring in developing countries. However, the epidemiological transition of chronic diseases (many of them preventable) replacing deaths from infectious diseases worldwide is well underway. Only the poorest countries still have infectious diseases among their 10 leading causes of death (WHO, 2011k). There are 150 million people worldwide who now have type 2 diabetes, and that number is projected to double by 2025 (Eiss and Glass, 2011). Unhealthy diet and lifestyle leading to obesity is fast becoming a common cause of global ill health.

Many infectious diseases are easily controlled or prevented by sanitation efforts and immunization programs. These types of preventive measures have been in wide use in developed countries for over a century. For this reason, people in developed countries have a better level of health, live longer, and eventually suffer and die from chronic illnesses. The most frequent diseases in developed countries are heart disease, stroke, and cancer (WHO, 2011k). Because these illnesses result in shorter morbidity and quicker mortality in regions with scarce resources, 80% of deaths caused by them in 2008 were in low- and middle-income countries. Globally, noncommunicable diseases now account for nearly two thirds of all deaths (United Nations News Centre, 2011).

In the twentieth century, the general trend was toward increasing life expectancy. That trend was diminished by the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Some areas, for example, India and parts of Africa, were more affected by the pandemic than others. HIV/AIDS has produced more devastation in poor countries with few economic resources and inferior health care infrastructures to fight the disease. Table 5-1 illustrates the relationship between health and economic status. Countries with relatively low standards of living have high infant mortality rates and a shorter life span; for example, Sierra Leone had an infant mortality rate of 165 per 1000 live births and a life expectancy of 38 years at the end of its civil war. As a country’s economic prospects improve, infant mortality rates fall, and life expectancy increases. For example, Japan has an infant mortality rate of 3 per 1000 live births and a life expectancy of 83 years (WHO, 2010f).

Major Global Health Problems

Worldwide health problems can be divided into two categories. First are the easily preventable conditions and treatable infectious diseases. These are the types of problems still common to developing countries. For the most part, these conditions are easy to fix with adequate numbers of health care personnel, improvements in sanitation, and sufficient funding. Other problems are more long-term ones. Chronic conditions are more frequent in developed countries, where the easily preventable and treatable conditions have, for the most part, been eliminated or controlled. Chronic conditions, which usually affect people as they age, are more complex to treat and require more economic resources, especially now that the obesity epidemic has spread to the poorest regions of the world as well.

Problems Common to Developing Countries

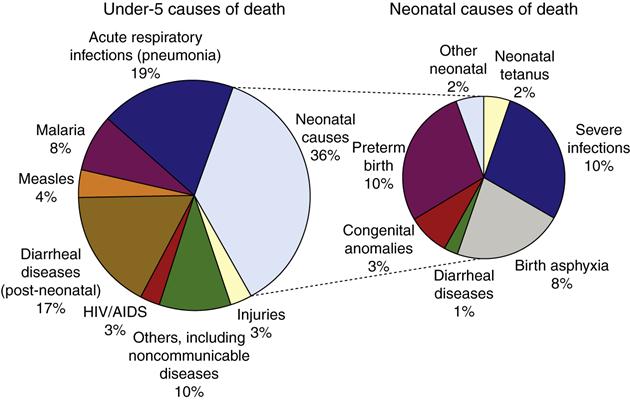

Unsafe water is a leading contributor to illness and death in developing countries, where nearly one billion people (14% of the world population) do not have safe water supplies. “Four percent of the global disease burden could be prevented if water supplies, sanitation and hygiene improved.” Two million deaths each year from diarrheal disease are caused by these deficits. “More than 50 countries still report cholera to the WHO.” The use of human wastewater for agricultural purposes in some countries also presents serious health risks (WHO, 2011m). This section highlights some of the major health problems in poor and developing countries. These include malnutrition related conditions, vector-borne diseases, and infectious diseases. The causes of death of children younger than 5 years of age, shown in Figure 5-2, are found mainly in developing countries, where they are highly correlated with malnutrition and the mothers’ lack of education (WHO, 2005, 2010a).

Malnutrition and Obesity

A contributing cause to about one third of deaths in children worldwide is undernutrition. The global recession which began in 2008 has increased the current risk of child malnutrition because of falling incomes and rising food prices. Although between 1990 and 2005, there was a global decline in the number of underweight children less than 5 years of age (from 25% to 18%), the progress has not steadily continued. Prevalence of undernutrition is increasing in some countries, and stunted growth affects many millions of children (WHO, 2010f).

Stunting of growth, manifested as height for age below normal standards, results from long periods of malnutrition. Damage caused by malnutrition during fetal development and the first two years of life may be irreversible. It is associated with lower intelligence quotient (IQ) scores and difficulties in school among children and less productivity and income among adults. Malnourished children whose mothers have little or no education are at greatest risk of stunting of growth. “In Nigeria, nearly one-half, and in India, nearly 60 percent of the children whose mothers had no education were stunted” (Population Reference Bureau, 2008a). Political unrest, intermittent warfare, and an increasing population contribute to the problem of stunted growth.

Substantial worldwide effort has led to a number of interventions, which have been somewhat successful in reducing malnutrition and starvation. Immediate food delivery to war-ravaged and famine-impacted countries provides only short-term help. Long-term activities, which are the major focus of worldwide efforts, include helping countries and their peoples with the following:

• Improvement of seed and farming techniques to produce better pest resistance and higher crop yield

• Education related to nutritional guidance, and family planning to space childbirth

The other end of the malnutrition spectrum is obesity. This is becoming a more obvious public health problem. In developing countries, well over 100 million people risk chronic illnesses and premature death from diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and stroke. “Aware that obesity is predominantly a ‘social and environmental’ disease, WHO is helping to develop strategies that will make healthy choices easier to make” (WHO, 2011a).

Diarrheal Diseases

Perhaps the most heartbreaking problem is death from diarrhea because it is easily controllable. Diarrhea continues to be the second leading cause of death from infectious diseases among children under age 5 (WHO, 2005). Diarrhea has many causes, most of which are associated with poor sanitation and contaminated water supplies. Cholera is one example of an illness that causes severe diarrhea. Diarrheal disease is exacerbated by poverty, lack of knowledge about the importance of personal hygiene and community sanitation, and lack of medical supplies and personnel. Reductions in mortality are the result of simple measures, including the following:

• Oral rehydration therapy to replace fluids and electrolytes (WHO/UNICEF oral rehydration salts)

• Encouraging women to breast-feed, whenever possible

• Improvements in sanitation and water supplies

• Immunizations for vaccine-preventable illnesses that produce diarrhea (e.g., measles and cholera)

The WHO has actively discouraged bottle-feeding because mothers in poor countries incorrectly use prepared formula. Canned formula is expensive, so mothers dilute the formula with water; as a result, infants do not receive adequate nutrition. The HIV/AIDS epidemic has complicated WHO’s policy against bottle-feeding. Mothers with HIV infection who are not receiving antiretroviral (ARV) therapy are advised not to breast-feed their children. If the mother is on ARV, the WHO/UNICEF/Joint United Nations Program recommends exclusive breast-feeding for the first 6 months of the infant’s life. This should be followed by breast-feeding along with replacement foods (UNICEF, 2011b). Breast-feeding should stop once a nutritionally adequate diet is available.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

The AIDS epidemic was first reported in 1981, and 30 years later, in 2011, there are more than 33 million people living with HIV/AIDS worldwide, with at least 2 million of them being children under 15 years of age. In 2009, cases of new infections were estimated to be 2.6 million, and AIDS deaths were recorded at 1.8 million (WHO, 2009b). There has been “a 16-fold increase in the number of people receiving antiretroviral therapy between 2003 and 2010,” although about 9 million eligible people are still not receiving it (WHO, 2011f). AIDS no longer appears on the list of 10 leading causes of death in high-income countries, where antiretroviral drugs are readily available (WHO, 2011k). Global coverage of services for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV exceeded 50% in 2009 (WHO, 2011l). It is expected that there will be much more widespread availability of AIDS medications as a result of the upcoming price concessions for 70 of the world’s poorest countries. The lower prices were negotiated with eight Indian pharmaceutical companies by British and American foreign aid organizations (McNeil, 2011). Effective treatment is crucial for the social and economic restoration of self-worth needed for patients to combat the HIV/AIDS stigma (Campbell et al., 2011). Table 5-2 shows the prevalence of HIV in different parts of the world.

Table 5-2

| Country | Prevalence % |

| Swaziland | 26.1 |

| Botswana | 23.9 |

| South Africa | 18.1 |

| Zimbabwe | 15.3 |

| Mozambique | 12.5 |

| Malawi | 11.9 |

| Tanzania | 6.2 |

| Uganda | 5.4 |

| Nigeria | 3.1 |

| Ethiopia | 2.1 |

| Jamaica | 1.6 |

| Thailand | 1.4 |

| United States | 0.6 |

| Brazil | 0.6 |

| Switzerland | 0.6 |

| Canada | 0.4 |

| Greece | 0.2 |

| Pakistan | 0.1 |

| Poland | 0.1 |

Data from World Health Organization (WHO). (2010). World health statistics 2010. Geneva: Author.

AIDS has disrupted the lives of many families, leaving their children with few adult supports. By the end of 2007, there were at least 15 million “AIDS orphans” worldwide, with 12 million of them in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS orphans are children under 18 who have lost one or both parents to AIDS (Orphans Against AIDS, 2011). Sometimes, whole families are ravaged by the disease, depriving children of their parents, grandparents, and other relatives and leaving them to scavenge for food and shelter to survive on their own.

International efforts have concentrated on primary prevention. A few examples of primary prevention efforts are education about the cause and spread of HIV; advocacy of the use of condoms and other protective measures during sexual activity; improvement in the procurement, storage, and administration of blood; and advocacy efforts aimed at women and men who are at risk because they have multiple sexual partners.

Early prevention work tended to focus on Western World theories of individual behavioral change. The field has moved toward broader attention on social groups and communities of hard-to-reach populations. This move required acknowledgment that target audiences will not adopt behaviors that are not within their cultural norm (McKee et al., 2004)

Many workplaces in Kenya are integrating activities toward combating HIV, especially peer education programs, into their daily operations. Employers have found that it is easier and cheaper to educate and/or treat employees than to train another person for the job vacated by someone who died from AIDS (Taravella, 2005). In 60 schools of the North East Province of Kenya, peer health educators are being trained for leading “chill clubs” to promote HIV/AIDS awareness and teach preventive strategies against the infection (United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS [UNAIDS], 2011).

Voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) is a major strategy of the HIV prevention and treatment programs in the community. With the help of trained counselors, people learn how to reduce their risk of infection. They can also learn about their HIV status and enroll for treatment, if necessary. A limited number of mobile VCT services exist, and they are helpful in getting more people tested (Kresge, 2006). A recent innovation in mobile VCT services is “moonlight voluntary counseling and testing,” in which HIV/AIDS counselors in remote areas of East Africa bring a tent at night to areas where alcohol and drugs are sold and thus do VCT work in a more confidential setting (because of the stigma) than those used in daytime VCT work (UNAIDS, 2011).

HIV has defeated efforts at vaccine development for almost 30 years. Failure of two promising vaccine candidates over the last 10 years raised concerns about whether a vaccine could ever be developed against the many existing subtypes of HIV. But in 2009, a large clinical trial in Thailand showed that even though protection afforded by the new vaccine candidate was only 31.2%, it brought hope for future prevention of HIV infection (Berkley, 2010; UNAIDS, 2009).

In the meantime, in the summer of 2011, news about two landmark preexposure prophylaxis studies in Africa was published in the popular literature as well as in public health reports. A new combination drug, Truvada, lowered the risk of infection by at least 63% in the treatment populations. “Such treatment-as-prevention strategies may curb the AIDS epidemic by blocking the spread of HIV before it can do more harm” (New Hope Against HIV, 2011).

Malaria

Malaria is the most important vector-transmitted disease in the world. It is spread by the bite of the plasmodium infected female Anopheles mosquito. It is endemic to most of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. In 2009, it caused at least 225 million cases and 781,000 deaths worldwide, with over 90% of deaths occurring in Africa among children under 5 years of age. Nearly half of the global population is at risk for the illness (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2011a).

A number of global partnerships for malaria eradication have been established during the past 10 years. These include the Roll Back Malaria control program; the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria; the World Bank program; and the U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative. The UN Millennium Development Goals discussed earlier also target malaria

Currently, the most recommended interventions for malaria control are being expanded in sub-Saharan Africa. Use of bed nets treated with insecticide has been shown to reduce child mortality and could save as many as 5.5 lives per 1000 children sleeping under the nets. Spraying the interior walls of houses with insecticide reduces malaria, especially when done throughout communities. Different sprays should be employed if vector resistance occurs. Clinical management of malaria involves outsmarting parasite resistance to first-line treatment such as chloroquine and using the new artemisinin derivatives with other antimalarials that have different modes of action. During pregnancy, both maternal anemia and placental disease are treated preventively with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine. Instituting these practices has resulted in far fewer inpatient cases and deaths from malaria in countries that can employ these prevention and treatment strategies. There is still no effective vaccine for malaria, although several are in development. A current clinical trial using an upgrade to a vaccine produced a 35% reduction in illness and a 49% reduction for up to 6 months in severe childhood malaria (CDC, 2011b).

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is the second leading infectious disease cause of death in adults worldwide (only HIV/AIDS exceeds it). The largest numbers of new cases occur in the WHO South-East Asia Region (WHO, 2010f). New smear-positive cases worldwide in 2008 were estimated to be 9.4 million, and over 1.8 million TB deaths occurred that year. Because people are often co-infected with TB and HIV/AIDS, “tuberculosis case rates have more than tripled, and deaths have quadrupled over the past 15 years in African countries with the highest rates of HIV infection.” The full scope of the problem is not clear because of inadequate surveillance data and diagnostic facilities in that part of the world (Center for Global Health Policy, 2010).

TB, by itself, is easily treated with medication, although effective drug therapy is not always available to people in developing countries. New drug-resistant strains of the TB-causing organism (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) are complicating the treatment regimen for TB. Most of these strains arose as a result of incomplete treatment or poorly supervised treatment. For this reason, in the countries with the highest rates, a short course of directly observed therapy (DOTS), in which medical supervision, drug therapy, and laboratory surveillance are combined to combat the disease, has become the standard treatment for TB. Individuals receiving DOTS are supervised as they take their medication for the entire treatment period, which can be from 6 months to 2 years. DOTS produces a remission rate of up to 95%. Globally, nearly all patients with TB under care are being treated using DOTS (WHO, 2009d).

As noted above, co-infection with HIV and M. tuberculosis is especially prevalent in Africa, and often results in death from TB. Co-infection complicates the treatment of each illness because each expedites the progression of the other. A significant contributor to new disease in countries with scarce resources for health care services is the ongoing transmission between patients with HIV and those with TB who congregate in clinic waiting areas (Center for Global Health Policy, 2010). The reservoirs of both multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) and extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB, which is resistant to almost all TB drugs) are steadily expanding. Globally, the WHO estimates that a half million new MDR cases occurred in 2007, with 85% of these in 27 specific countries (WHO, 2010f). Medicines for patients with MDR-TB are 50 to 200 times more expensive compared with standard drugs, and “one case of XDR-TB can cost $600,000 or more to treat,” with death as likely an outcome as cure (Center for Global Health Policy, 2010).

The Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine, the only TB vaccine, offers limited protection for children and is not protective against pulmonary TB in adults. Efforts to develop a more effective vaccine are underway in the United States and Europe by two nonprofit organizations supported by charities such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. They are hopeful that “the first new TB vaccine could be ready for use by 2016” (Cookson, 2010).

Vaccine-Preventable Diseases and Integrated Management of Childhood Illness

In the poorest countries of the world, nearly 11 million children under 5 years of age die every year from easily preventable and treatable illnesses such as diarrhea, lower respiratory tract infections, measles, and malaria. Malnutrition contributes to half of these deaths. Most of these children die at home, and at least 40% of those that died never received any treatment at a health facility (UNICEF, 2009).

The WHO Expanded Program of Immunization (EPI) was the first global effort to immunize children against vaccine-preventable diseases. The resulting increase in vaccination delivery was further improved with the formation of the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations (GAVI), a public–private enterprise to boost child vaccination rates. Despite these efforts, the same preventable illnesses have continued to kill thousands of children annually. In recent years, the WHO and the UNICEF developed the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) program. It has been adopted into the health systems of over 80 countries, with the main areas of focus on “improving health worker skills, improving health systems, and improving family and community practices.” All of these efforts have resulted in 78% fewer deaths from measles worldwide between 2000 and 2008. However, measles is still a leading cause of death among children, with most of the 164,000 deaths from measles occurring globally in 2008 in the under-5 age group (WHO, 2009c). Figure 5-3 shows preparations for vaccine administration at a rural health care facility.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree