Chapter 6 Gastroenterology

Basic concepts

1 What is the major stimulus for gastrin secretion? What are the physiologic actions of gastrin in the stomach?

3 What are the primary hormonal stimuli for the pancreatic exocrine secretions and how do these secretions differ in content?

4 What are the primary stimuli for the secretion of cholecystokinin and secretin and from where are these hormones secreted?

8 What defines the foregut, midgut, and hindgut anatomically? Which main arteries provide the blood supply to each segment? What nerves supply these regions?

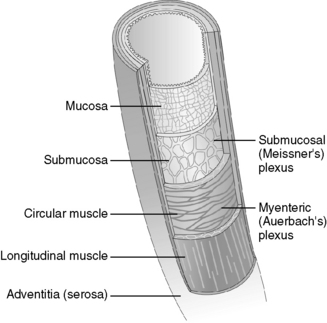

9 What are the anatomic layers of the gut wall?

From the lumen out, the layers of the GI tract are as follows: (1) mucosa, comprising the mucosal epithelium, lamina propria, and muscularis mucosae; (2) submucosa, which contains the submucosal (Meissner’s) nerve plexus; (3) muscularis propria, comprising an inner circular smooth muscle layer, myenteric plexus, and outer longitudinal smooth muscle layer; and (4) serosa (adventitia), which is the fibrous outer covering (Fig. 6-1).

Figure 6-1 Layers of the gut wall.

(From Brown TA: Rapid Review Physiology. Philadelphia, Mosby, 2007.)

1 What is the differential diagnosis?

Case 6-1 continued:

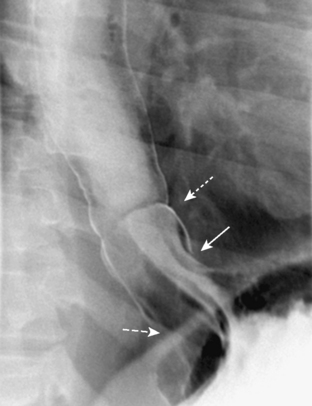

Physical examination is significant for obesity. There is no chest wall tenderness. Cardiac examination is unremarkable, except for auscultating bowel sounds in the patient’s chest. A cardiac stress test is negative for inducible ischemia. A barium swallow is shown in Figure 6-2.

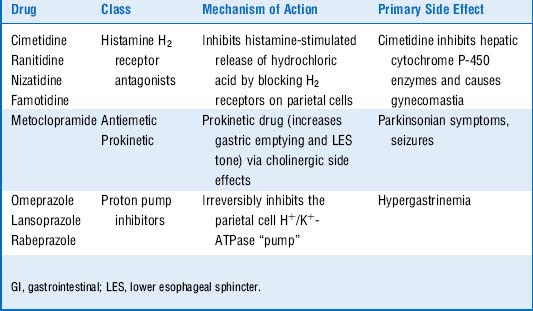

4 Cover the far left column of Table 6-1 and attempt to name the drugs used in the treatment of GERD based on the class of drug, the mechanism of action, and the primary side effects listed in the table

5 Which of the drugs in Table 6-1 are contraindicated in a patient in whom bowel obstruction is suspected and why?

6 Why may the omeprazole this patient was given cause him to develop hypergastrinemia?

7 Which complications of gastroesophageal reflux disease could be responsible for the patient’s difficulty swallowing?

8 Differentiate between the two types of esophageal cancers—adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma—in terms of risk factors and location

9 Why would a patient with Sjögren’s syndrome be more susceptible to esophageal pathology in gastroesophageal reflux disease?

Summary Box: Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease, Hiatal Hernias, and Esophageal Carcinomas

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) classically presents with regurgitation of “sour” contents into the esophagus or oropharynx and substernal chest discomfort that worsens after large meals and when in a recumbent position.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) classically presents with regurgitation of “sour” contents into the esophagus or oropharynx and substernal chest discomfort that worsens after large meals and when in a recumbent position.

The pathogenesis of GERD involves inappropriate relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES).

The pathogenesis of GERD involves inappropriate relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES).

Sliding hiatal hernias can predispose to GERD. Paraesophageal “rolling” hiatal hernias are subject to incarceration.

Sliding hiatal hernias can predispose to GERD. Paraesophageal “rolling” hiatal hernias are subject to incarceration.

GERD is typically treated with proton pump inhibitors, H2 receptor antagonists, or surgery (Nissen fundoplication in refractory cases).

GERD is typically treated with proton pump inhibitors, H2 receptor antagonists, or surgery (Nissen fundoplication in refractory cases).

Long-term complications of GERD include Barrett’s esophagus, adenocarcinoma, esophageal stricture, and esophageal ulceration.

Long-term complications of GERD include Barrett’s esophagus, adenocarcinoma, esophageal stricture, and esophageal ulceration.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a board favorite. Be able to recognize the symptoms of chest pain following meals (may be described as a burning sensation in the chest), sour taste in the mouth, and nocturnal cough as a classic presentation for this condition. You should also know how to recognize complications of GERD (e.g., Barrett’s esophagus, strictures, adenocarcinoma) by both medical history and histologic appearance (refer to Chapter 27, Pathology, for images).

1 In pathophysiologic terms, how do you approach dysphagia?

Dysphagia can be approached in terms of oropharyngeal or esophageal etiology.

Case 6-2 continued:

The patient also notes occasional chest pain with eating, nocturnal cough, and an unintentional 15-lb weight loss in the last 2 months. She was recently admitted to the hospital for treatment of pneumonia. Esophageal manometry shows increased LES pressure with incomplete LES relaxation and a complete absence of peristalsis in the lower esophagus. A barium swallow is shown in Figure 6-3.

2 What is the likely diagnosis in this woman? Describe the pathophysiology of this disease

The LES is normally tonically constricted, generating enough intraluminal pressure to prevent the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus. During the esophageal phase of swallowing, the LES relaxes in response to a food bolus descending through the esophagus, a phenomenon referred to as receptive relaxation. In achalasia, there is destruction of the myenteric plexus, which mediates receptive relaxation and also mediates esophageal peristalsis (hence the aperistalsis). Although the exact mechanism of increased LES tone in patients with achalasia is not known, research suggests that these patients have loss of nitric oxide–secreting neurons, a key factor in LES relaxation. The failure of the LES to relax together with the failure of the distal esophagus to undergo peristalsis allows food to accumulate and dilate the lower esophagus, creating the “bird’s beak” appearance on barium swallow (Fig. 6-3).

3 Chagas’ disease is also known to be a cause of achalasia. What is the pathologic mechanism and what organism is the primary culprit?

5 In addition to pneumatic dilatation of the lower esophageal sphincter and surgical myotomy, injection of botulinum toxin into the lower esophageal sphincter is a treatment option for this woman. What is this drug’s mechanism of action in this context?

Because it is a motility disorder, patients with achalasia typically present with dysphagia to both solids and liquids.

Because it is a motility disorder, patients with achalasia typically present with dysphagia to both solids and liquids.

Achalasia is caused by destruction of the myenteric (Auerbach’s) plexus. In Chagas’ disease, this destruction is mediated by the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi.

Achalasia is caused by destruction of the myenteric (Auerbach’s) plexus. In Chagas’ disease, this destruction is mediated by the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi.

Esophageal manometry will classically show distal aperistalsis and increased LES tone.

Esophageal manometry will classically show distal aperistalsis and increased LES tone.

Barium swallow will show a “bird’s beak” appearance.

Barium swallow will show a “bird’s beak” appearance.

Treatment options include LES dilatation, LES myotomy, and injection of botulinum toxin into the LES.

Treatment options include LES dilatation, LES myotomy, and injection of botulinum toxin into the LES.

2 If you were this man’s physician, what would you have done differently in the treatment of this patient?

3 How are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs thought to predispose to the formation of gastric ulcers? What alternatives exist to lessen gastrointestinal side effects?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree