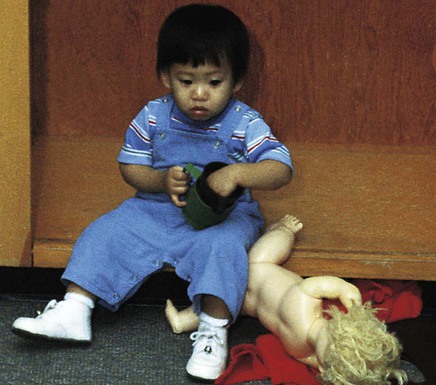

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Identify the stressors of illness and hospitalization for children during each developmental stage. • List essential priorities of nursing care on a child’s admission to the hospital. • Review nursing interventions that prevent or minimize the stress of separation during hospitalization. • Discuss nursing interventions that minimize the stress of loss of control during hospitalization. • Describe nursing interventions that minimize the fear of bodily injury during hospitalization. • Outline nursing interventions that support parents, siblings, and family during a child’s illness and hospitalization. • Describe nursing interventions needed when children are admitted to special units such as the emergency department. Often illness and hospitalization are the first crises children must face. Especially during the early years, children are particularly vulnerable to these stressors because (1) stress represents a change from the usual state of health and environmental routine, and (2) children have a limited number of coping mechanisms to resolve stressors. Major stressors of hospitalization include separation, loss of control, bodily injury, and pain. Children’s reactions to these crises are influenced by their developmental age; their previous experience with illness, separation, or hospitalization; their innate and acquired coping skills; the seriousness of the diagnosis; and the support system available. Children also expressed fears caused by the unfamiliar environment or lack of information; child-staff relations; and the physical, social, and symbolic environment (Samela, Salanterä, and Aronen, 2009). The major stress from middle infancy throughout the preschool years, especially for children ages 6 to 30 months, is separation anxiety, also called anaclitic depression. The principal behavioral responses to this stressor during early childhood are summarized in Box 38-1. During the stage of protest, children react aggressively to the separation from the parent. They cry and scream for their parents, refuse the attention of anyone else, and are inconsolable in their grief (Fig. 38-1). In contrast, through the stage of despair, the crying stops, and depression is evident. The child is much less active, is uninterested in play or food, and withdraws from others (Fig. 38-2). Because children seem to react “negatively” to visits by their parents, uninformed observers feel justified in restricting parental visiting privileges. For example, during the protest stage children outwardly do not appear happy to see their parents (Fig. 38-3). In fact, they may even cry louder. If they are depressed, they may reject their parents or begin to protest again. Often they cling to their parents in an effort to ensure their continued presence. Consequently such reactions may be regarded as “disturbing” the child’s adjustment to the new surroundings. If the separation has progressed to the phase of detachment, children respond no differently to their parents than they would to any other person. Previous research, usually based on adult recollections, indicated that the family does not play as important a role for school-age children as it does during the toddler and preschool years. However, in a recent study that asked children about their fears when hospitalized, children listed their greatest fears regarding hospitalization as being separated from family and friends, being in an unfamiliar environment, receiving investigations or treatments, and losing self-determination or choices (Coyne, 2006). In a qualitative study of children ages 5 to 9 years, children described hospitalization in stories that focused on being alone and feeling scared, angry, or sad. These children also described the need for protection and companionship while hospitalized (Wilson, Megel, Enenbach, et al., 2010). Children may react to the stresses of hospitalization before admission, during hospitalization, and after discharge. A child’s concept of illness is even more important than age and intellectual maturity in predicting the level of anxiety before hospitalization (Clatworthy, Simon, and Tiedeman, 1999). This may or may not be affected by the duration of the condition or prior hospitalizations; therefore nurses should avoid overestimating the illness concepts of children with prior medical experience (Box 38-2). A number of risk factors make certain children more vulnerable than others to the stresses of hospitalization (Box 38-3). Rural children may exhibit significantly greater degrees of psychologic upset than urban children, possibly because urban children have opportunities to become familiar with a local hospital. Because separation is such an important issue surrounding hospitalization for young children, children who are active and strong willed tend to fare better when hospitalized than youngsters who are passive. Consequently nurses should be alert to children who passively accept all changes and requests; these children may need more support than “oppositional” children. The stressors of hospitalization may cause young children to experience short- and long-term negative outcomes. Adverse outcomes may be related to the length and number of admissions, multiple invasive procedures, and the parents’ anxiety. Common responses include regression, separation anxiety, apathy, fears, and sleeping disturbances, especially for children younger than 7 years of age (Melnyk, 2000). Supportive practices such as family-centered care and frequent family visiting may lessen the detrimental effects of such admissions. Nurses should attempt to identify children at risk for poor coping strategies (Small, 2002). The pediatric population in hospitals has changed dramatically over the past two decades. With a growing trend toward shortened hospital stays and outpatient surgery, a greater percentage of the children hospitalized today have more serious and complex problems than those hospitalized in the past. Many of these children are fragile newborns and children with severe injuries or disabilities who have survived because of major technologic advances yet have been left with chronic or disabling conditions that require frequent and lengthy hospital stays. The nature of their conditions increases the likelihood that they will experience more invasive and traumatic procedures while they are hospitalized. These factors make them more vulnerable to the emotional consequences of hospitalization and result in their needs being significantly different from those of the short-term patients of the past (see Chapter 36 for further discussion on children with special needs). Most of these children are infants and toddlers, the age-group most vulnerable to the effects of hospitalization. Although hospitalization can be and usually is stressful for children, it can also be beneficial. The most obvious benefit is the recovery from illness, but hospitalization also can present an opportunity for children to master stress and feel competent in their coping abilities. The hospital environment can provide children with new socialization experiences that can broaden their interpersonal relationships. The psychologic benefits need to be considered and maximized during hospitalization. Appropriate nursing strategies to achieve this goal are presented on pp. 1121-1122. The crisis of childhood illness and hospitalization affects every member of the family. Parents’ reactions to illness in their child depend on a variety of factors. Although one cannot predict which factors are most likely to influence their response, a number of variables have been identified (Box 38-4). Recent research has identified common themes among parents whose children were hospitalized, including feeling an overall sense of helplessness, questioning the skills of staff, accepting the reality of hospitalization, needing to have information explained in simple language, dealing with fear, coping with uncertainty, and seeking reassurance from caregivers. This reassurance involves staff being compassionate, expressing concern for the child, and attending to detail in the child’s care (Stranton, 2004). Siblings’ reactions to a sister’s or brother’s illness or hospitalization are discussed in Chapter 36 and differ little when a child becomes temporarily ill. Siblings experience loneliness, fear, worry, anger, resentment, jealousy, and guilt. Illness may also result in children’s loss of status within their family or social group. Various factors have been identified that influence the effects of the child’s hospitalization on siblings. Although these factors are similar to those seen when a child has a chronic illness, Craft (1993) reported that the following factors regarding siblings are related specifically to the hospital experience and increase the effects on the sibling: • Being younger and experiencing many changes • Being cared for outside the home by care providers who are not relatives • Receiving little information about their ill brother or sister • Perceiving that their parents treat them differently compared with before their sibling’s hospitalization Parents are often unaware of the number of effects that siblings experience during the sick child’s hospitalization and the benefit of simple interventions to minimize these effects such as explicit explanations about the illness and provisions for the siblings to remain at home. Sibling visitation is usually beneficial to the patient, sibling, and parent but should be evaluated on an individual basis. Siblings should be prepared for the visit with developmentally appropriate information and be given the opportunity to ask questions. The nursing admission history refers to a systematic collection of data about the child and family that allows the nurse to plan individualized care. The nursing admission history presented in Box 38-5 is organized according to the Functional Health Patterns outlined by Gordon (2002) (see Nursing Diagnosis, Chapter 26). This assessment framework is a guideline for formulating nursing diagnoses. One of the main purposes of the history is to assess the child’s usual health habits at home to promote a more normal environment in the hospital. Therefore questions related to activities of daily living in the nutritional-metabolic, elimination, sleep-rest, and activity-exercise patterns are a major part of the assessment. The questions found under the health perception–health management pattern are directed toward evaluation of the child’s preparation for hospitalization and are key factors in determining whether additional preparation is needed. The questions included in the self-perception–self-concept and role-relationship patterns offer insight into the child’s potential reaction to hospitalization, especially in terms of separation. The nurse should also inquire about the use of any medications at home, including complementary medicine practices (Box 38-6). In a study of children with cancer, 42% had used alternative or complementary therapies simultaneously with or after conventional treatments (Fernandez, Pyesmany, and Stutzer, 1999). It is important that the use of any herbal or complementary therapy be noted in a preoperative assessment because of possible anesthesia or surgical complications related to herbal products (Flanagan, 2001) (see Critical Thinking Case Study).

Family-Centered Care of the Child During Illness and Hospitalization

Stressors of Hospitalization and Children’s Reactions

Separation Anxiety

Later Childhood and Adolescence

Effects of Hospitalization on the Child

Individual Risk Factors

Changes in the Pediatric Population

Beneficial Effects of Hospitalization

Stressors and Reactions of the Family of the Child Who is Hospitalized

Parental Reactions

Sibling Reactions

Nursing Care of the Child Who is Hospitalized

Preparation for Hospitalization

Admission Assessment

Family-Centered Care of the Child During Illness and Hospitalization

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access