Evaluation of Nursing Care with Communities

Claudia M. Smith and Frances A. Maurer

Focus Questions

What are the steps in evaluation?

What questions can be answered by evaluation?

What outcomes are indicators of the effectiveness of nursing interventions with communities?

How can evaluation of process be used to improve the operation of nursing programs?

How is evaluation used to modify nursing care with communities?

Key Terms

Adequate

Affective learning

Appropriate

Effective

Efficiency

Evaluation

Formative evaluation

Outcome measures

Result

Satisfaction

Summative evaluation

Evaluation of care with communities seeks to determine whether health has improved. Were the desired health goals reached? How much progress was made toward the goals? What themes, patterns, and results emerged? What side effects were evident? How have community competence and resilience been enhanced? To what extent are the community changes sustainable? Evaluation provides information to help community/public health nurses improve the quality of their nursing practice.

Responsibilities in evaluation of nursing care with communities

Evaluation is the process by which a nurse judges the value of nursing care that has been provided. As with any type of nursing care, the community/public health nurse seeks to determine the degree to which planned goals were achieved and to describe any unplanned results.

The purpose of the evaluation is to facilitate additional decision making. An evaluation might conclude that what had been done could not have been done better, that the goals were reached, and that the goals were mutually desirable to the nurse and the community members. This conclusion would be cause for celebration. As a result of another evaluation, the conclusion might be that alterations are needed in the plan of care to reach the desired outcomes more effectively; or possibly that, although goals were reached, the cost in money, time, or other resources was too expensive for the nurse or the community members.

Evaluation is based on several assumptions: first, that nursing actions have results, both intended and unintended; second, that nurses are accountable for their own actions and care provided; and third, that different sets of actions result in resources being used differently (i.e., some nursing interventions use more resources than others).

Evaluation involves two parts: measurement and interpretation. Many different schemes or models exist for organizing ideas about evaluation, which may result in confusion among people who use different terminology for similar concepts.

Basic to the nursing process, however, is the idea of measuring whether planned goals were achieved. Synonyms for this activity and its result are outcome attainment (Donabedian, 1980), performance evaluation (Suchman, 1967), results of effort, and evaluation of effectiveness (Deniston & Rosenstock, 1970). The question that the nurse attempts to answer is, “Were the planned goals achieved?”

Another basic idea addresses the quality of the results and the process that contributed to the results. Some terms used to express this idea are as follows:

• Appropriate—suitable for a particular occasion or use; fitting

• Adequate—able to fill a requirement; sufficient or satisfactory

Each of these terms describes different aspects of measuring quality. The following are some questions that may be asked about quality. How and why did the interventions work? Were the nurses’ actions ethical? Did the nurses address the most important goals? Did the nurses involve community members and recipients as participants (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2007)? Were resources used wisely? How many needs and goals did the plan actually address?

Responsibilities of Baccalaureate-Prepared Community/Public Health Nurses

According to the American Nurses Association (ANA) (2007), community/public health nurses with bachelor’s degrees in nursing are expected to work with advanced practice public health nurses (masters prepared) and community members in evaluating responses of the community to nursing interventions.

The responsibilities of community/public health nurses for evaluating nursing care with communities vary, depending on the size and complexity of the community and whether the community is geopolitical or phenomenological (see Chapter 15).

Baccalaureate-prepared community/public health nurses are expected to work with community members, advanced public health nurses, and multidisciplinary teams to evaluate nursing care with geopolitical communities. Community/public health nurses may also work with multidisciplinary teams and nurses who engage in quality assurance and accreditation reviews (ANA, 2007). Baccalaureate-prepared community/public health nurses will be more capable members of evaluating teams if they have been introduced in their education to ideas and skills in evaluating nursing care with communities.

In some instances, a baccalaureate-prepared community/public health nurse will work with a small phenomenological community, such as a senior center or school; in this case, the nurse is likely to evaluate his or her own performance with minimal assistance from a supervisor and peers. Either independently or with help from supervisors, community/public health nurses are expected to evaluate the effectiveness of intervention programs that involve teaching, direct care, and screening and referral.

Regardless of the type or size of community, the members themselves should, when possible, be involved in planning and conducting the evaluation (ANA, 2007). The measurement of many health outcomes requires the judgment of the community members themselves.

Formative and Summative Evaluations

When is nursing care with communities evaluated? Evaluation of the effectiveness of care that takes place after the interventions have been performed is known as summative evaluation because the nurse is evaluating the sum, the bottom line, the end results. Summative evaluation involves measurement of community responses to nursing care and interpretation of the degree to which planned goals were met. Summative evaluation usually consists of measurement of outcomes and goal attainment.

Summative evaluation may also take place several months or years after nursing care has been provided. This evaluation seeks to determine whether a long-term impact was made on the health status and the health responses of the community.

Formative evaluation is evaluation that occurs throughout the nursing process but before evaluation of the outcomes of care. This evaluation occurs during the formation of the nursing care and during the process of its actual delivery. In other words, formative evaluation considers the day-to-day provision of programs of nursing care. Formative evaluation allows ongoing modification of nursing practices.

In the formative example just mentioned, the nurse can take action to remediate some of the problems identified during the intervention process. For example, the nurse might take the names of participants and deliver the printed material to them at some later date. The nurse had the seniors move into a small group in the room and found and used a microphone to help with the presentation.

Community Involvement

Because the community members are involved in evaluation, at least part of the evaluation must occur in the clients’ community. Mutuality is an important aspect of evaluation. Because much of the impact of the community/public health nurse is indicated by self-care and lifestyle changes of community members, a nurse must document and validate outcomes directly with community members. Additionally, although goals have been achieved, some negative or unexpected results might also have occurred. The nurse must explore the perceptions of community members to discover and validate the meaning of the experience. Determining how satisfied community members are with both the outcomes and the nursing interventions is important.

Stakeholders are individuals who have expectations about nursing care but who are not directly involved in its delivery. For example, there are individuals whose approval was necessary, those who contributed money or supplies, those who volunteered to assist, and those (such as competitors) for whom the presence of nursing services had an impact. Stakeholders in a community immunization campaign might be the county health officer, a retail pharmacist who donates syringes, a local pediatrician who is concerned about financial competition, and parents of persons who were immunized. Community health/public nurses need to identify the stakeholders and invite them to participate in evaluation.

Standards for a Good Evaluation

Standards for evaluation of nursing care with communities have been formulated by the Quad Council of Public Health Nursing Organizations and published by the ANA (2007):

Steps in evaluation

Evaluation is a process that includes several steps: planning, collecting the data, analyzing and interpreting the data, providing recommendations, reporting the results, and implementing the recommendations (McKenzie et al., 2009). Box 17-1 identifies evaluation activities in greater detail related to each of the major steps.

Questions answered by evaluation

Evaluation of nursing care with communities involves evaluation of programs of care for populations. Program evaluation includes evaluation of outcomes (program goals and outcome objectives), as well as evaluation of the structures and processes used to achieve the outcomes (Ervin, 2002). The ANA considers outcomes, structures, and processes as the primary categories of criteria to be used to measure the quality of nursing care. Outcomes are the end results; structures are the social and physical resources; and processes are the “sequence of events and activities” (ANA, 1986, p. 18) used by the nurse during the delivery of care. For example, evaluation of a health program designed to identify adults with high cholesterol levels would include the following:

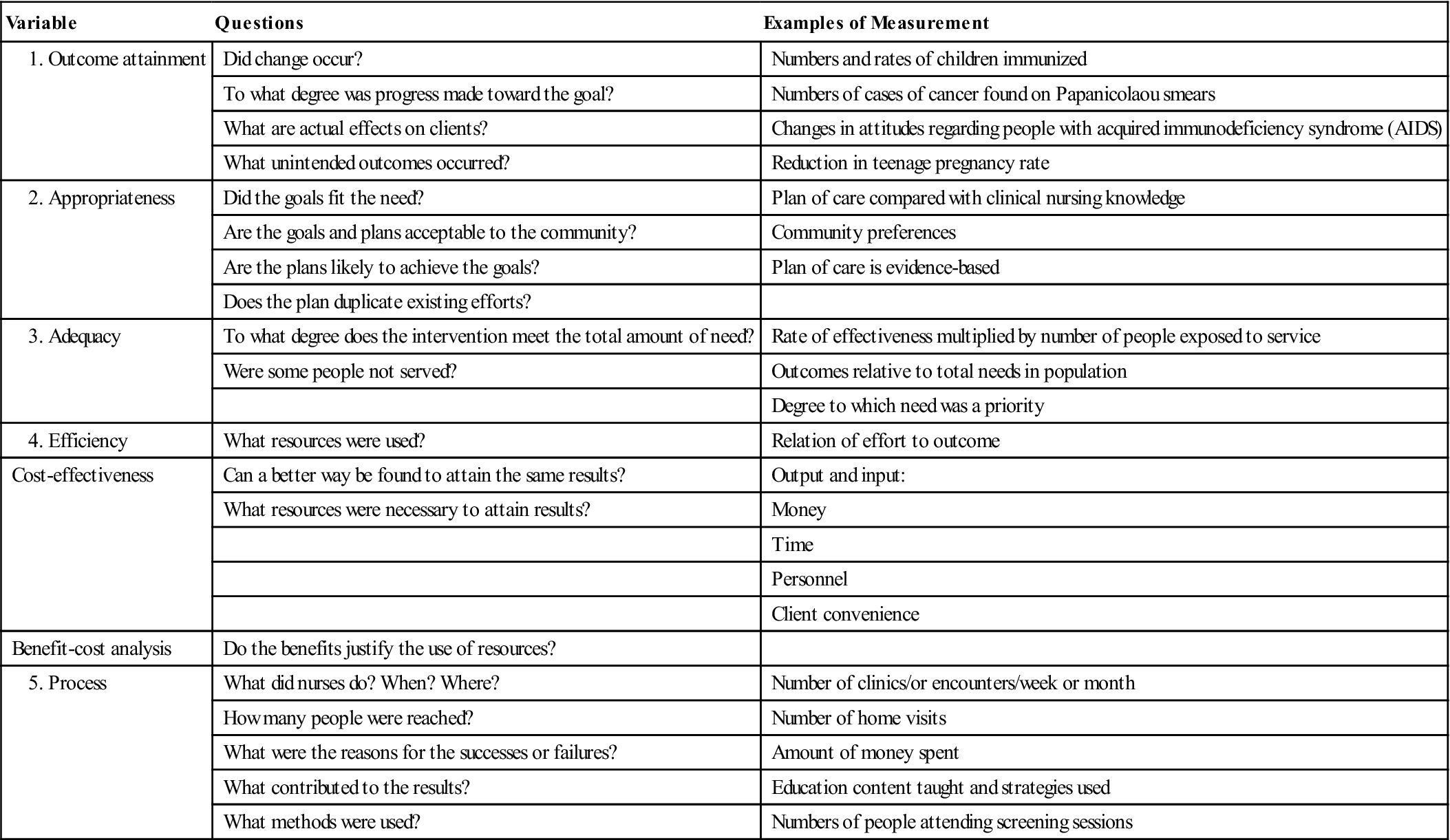

Table 17-1 describes the following five categories of questions that can be answered by evaluation: (1) outcome attainment, also called effectiveness; (2) appropriateness of care; (3) adequacy of care in relation to the scope of the problem; (4) relationship of resources to results, also called efficiency; and (5) process. This set of questions includes the criteria of outcome, structure, and process evaluation and adds appropriateness and adequacy. Questions of appropriateness and adequacy evaluate the nursing care program in relation to the community health needs. Efficiency addresses the relationship of outcomes to structures and processes. Each of these sets of evaluation questions is discussed in more detail.

Table 17-1

Questions Answered by Evaluation

| Variable | Questions | Examples of Measurement |

| Did change occur? | Numbers and rates of children immunized | |

| To what degree was progress made toward the goal? | Numbers of cases of cancer found on Papanicolaou smears | |

| What are actual effects on clients? | Changes in attitudes regarding people with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) | |

| What unintended outcomes occurred? | Reduction in teenage pregnancy rate | |

| Did the goals fit the need? | Plan of care compared with clinical nursing knowledge | |

| Are the goals and plans acceptable to the community? | Community preferences | |

| Are the plans likely to achieve the goals? | Plan of care is evidence-based | |

| Does the plan duplicate existing efforts? | ||

3. Adequacy | To what degree does the intervention meet the total amount of need? | Rate of effectiveness multiplied by number of people exposed to service |

| Were some people not served? | Outcomes relative to total needs in population | |

| Degree to which need was a priority | ||

4. Efficiency | What resources were used? | Relation of effort to outcome |

| Cost-effectiveness | Can a better way be found to attain the same results? | Output and input: |

| What resources were necessary to attain results? | Money | |

| Time | ||

| Personnel | ||

| Client convenience | ||

| Benefit-cost analysis | Do the benefits justify the use of resources? | |

5. Process | What did nurses do? When? Where? | Number of clinics/or encounters/week or month |

| How many people were reached? | Number of home visits | |

| What were the reasons for the successes or failures? | Amount of money spent | |

| What contributed to the results? | Education content taught and strategies used | |

| What methods were used? | Numbers of people attending screening sessions |

Data from Deniston, O., & Rosenstock, I. (1970). Evaluating health programs. Public Health Reports, 85(9), 835–840; Donabedian, A. (1980). The definition of quality and approaches to its assessment (Vol. 1). Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press; Freeman, R. (1963). Public health nursing practice (3 rd ed.). Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders; and Suchman, E. (1967). Evaluative research: Principles and practice in public service and social action programs. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Evaluation of Outcome Attainment

Evaluation of outcome attainment, also called effectiveness, addresses the results of nursing interventions. Change toward predetermined goals, as well as unplanned effects, may have occurred (see Table 17-1). Frequently, large health programs are evaluated as a total intervention, without distinguishing the effects of nursing interventions from the effects of other health disciplines and program components. Therefore nursing care may be lumped into a single evaluation for the whole program rather than being evaluated as a separate intervention. Devising evaluation strategies and criteria for each component of a program is more useful because evaluators are given a better idea of which strategies are effective and which might need to be revised or eliminated. Evaluators can then determine nurse-sensitive outcomes. This is also true for multifaceted community/ public health nursing programs; knowing which nursing intervention is contributing to which outcome is more helpful.

Evaluation of outcome attainment evaluates changes in the population, the health care system within the community, or the environment. Box 17-2 identifies several variables that can be used as outcome measures of community health. Changes can occur in the population’s knowledge, behavior and skills, attitudes, emotional well-being, and health status.

When evaluating the health of a community, more than the outcomes of the population must be considered. Because the interaction of people in their environment facilitates or hinders health, variables such as the presence of health services, the satisfaction and acceptance of such programs, the presence of policies, and a harmonious balance with the environment must also be considered. Each of these variables, which are used as an outcome measure of the health of populations or communities, is discussed in more detail. Each of these variables can be used as a measure of the effectiveness of specific community/public health nursing interventions.

Knowledge

A great deal of client teaching and health education is evaluated by measuring the health-related information that the individual, group, or population has obtained. Although information alone does not result in behavior changes, having information will often increase the possibility of behavior changes. For example, just because a father knows how to prepare infant formula in the proper concentration and with adequate asepsis does not ensure that he will actually do so. However, if he does not have that information, the only way he can prepare the formula would be by trial and error or by chance. Having the information increases the probability that the formula will be prepared properly.

When evaluating populations, surveys may be used to determine knowledge about specific health-related topics. These surveys may be conducted as interviews or through written questionnaires (Polit & Beck, 2010). When working with populations, the community/public health nurse is interested in the proportion of the population that the teaching reached and the proportion that retained the information presented. Having information is not sufficient for healthy living; the information must be put to use.

Behaviors and Skills

Integrating health-related behaviors and skills into daily living affects health status—raising children, caring for an older bed-bound family member, seeking a prostate examination, and preparing nutritious foods require action. These actions are labeled competent or skilled if they are consistent with existing knowledge and if they are performed in an effective and efficient manner.

Health behaviors may change as a result of interventions performed by community/public health nurses (see Chapters 18 and 20 for more details regarding health promotion and health teaching).

When evaluating health behaviors of populations, the nurse’s interest is in the proportion of the population who engage in such behaviors. The usual way to collect information about health behaviors is to ask people what they do. However, people do not always provide accurate reports because they may have forgotten information or want to look good to the surveyor.

Some data on health behaviors, such as use of a specific health service, can also be collected from client health records and health care information systems. For example, immunization rates can be determined for populations of preschool children receiving Medicaid or enrolled in a specific managed care organization by monitoring whether immunizations have been received.

Time and money often limit the degree to which behavior change can be measured. Observing the behavior of populations helps confirm the accuracy of what is reported; however, this process takes much more time and money. Asking people to make a contract with themselves to make a commitment to specific actions has been shown to increase the likelihood that the actions will be performed (Sloan & Schommer, 1991). Therefore when measuring actual behavioral changes of populations is not possible, community/public health nurses can measure the degree to which people commit to specific actions.

Attitudes

Attitudes include opinions and preferences about ideas, people, and things. Persons have attitudes about the concept of health and the ways in which health may be attained and maintained. Because attitudes predispose the selection of some actions over others, attitudes are a health-related measure. For example, if a population generally views health as the ability to perform work, people may take cold medication to allow them to feel well enough to go to work. However, a group may not alter their high-cholesterol diets because their current diets do not interfere with their immediate ability to work.

Community attitudes also predispose the population to support or work against various policies and services. For example, if the dominant community attitude toward criminals is that they should be punished and live stark lives, there may be little support for prison health services. If the predominant community attitude is that health prevention can reduce human suffering and dollars spent for care of the ill, there may be more support for prison health services.

Attitudes toward health and health behavior can be changed through planned or spontaneous experiences. Attitudinal change is also called emotional learning or affective learning. Attitudes of populations can be measured before and after an intervention to determine whether affective learning has occurred. Changes in attitude may predispose people to change their behaviors. For example, as more members of a population adopt the attitude that smoking is undesirable, smoking rates decrease. In some neighborhoods, volunteer or paid members of the community are trained by community/public health nurses to address attitudes of community members about obtaining health care services such as mammography screening, prenatal care, and treatment for substance abuse.

Emotional Well-Being and Empowerment

Emotional well-being in a population can be measured by the proportion of members who experience self-esteem and satisfaction with their lives. Emotional well-being of a community can be measured also by assessing the existing structures and processes to strengthen human development and connectedness.

Improved quality of life is another outcome related to human well-being.

Criteria for emotional well-being of a community also include the degree of acceptance and cohesion among members and patterns of support, socialization, and decision making. When community members participate in the decision making that leads to goal achievement, perceptions of self-efficacy are enhanced. Self-efficacy is the belief that an individual can influence his or her environment and circumstances. Self-efficacy contributes to self-concept and is necessary if community members are to have an impact on their health.

Health Status

An ultimate measure of the effectiveness of health services and programs is the health status of the population. Community/public health programs seek to reduce premature deaths, disabilities, and injuries. Health status is measured using epidemiological statistics about morbidity and mortality (see Chapter 7). Epidemiological statistics that are collected for geopolitical communities do not distinguish the effects of nursing interventions from the effects of other health disciplines and programs. However, epidemiological statistics can be used to evaluate changes in health status that result from nursing interventions.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree