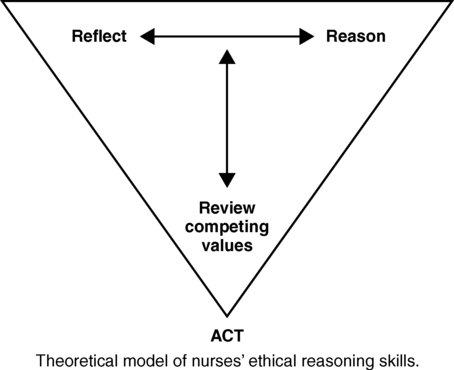

After studying this chapter, students will be able to: • Differentiate between values, morals, ethics, and bioethics. • Explain the difference between Kohlberg’s and Gilligan’s approaches to moral reasoning. • Identify and define basic ethical principles. • Discuss the concept of justice as an ethical principle in health care delivery. • Discuss the relevance of a code of ethics for the profession of nursing. • Understand how professional ethics override personal ethics in professional settings. • Describe ethical dilemmas resulting from conflicts between patients, health care professionals, family members, and institutions. • Identify a model for ethical decision making and discuss the steps of the model. • Discuss the effect of ethical issues on nurses and other health care professionals. • Recognize sociocultural challenges to professional ethical behavior, including social media and substance abuse. • Understand the important ethical issues related to immigration, migration, and health care. To enhance your understanding of this chapter, try the Student Exercises on the Evolve site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Black/professional. Chapter opening photo from Photos.com. Throughout their education and practice, nurses must exercise judgment when making clinical decisions. However, when nurses encounter ethical dilemmas, they need an ethical decision-making model to apply to the situation and one that works for individual nurses in the context of their own value system. Box 5-1, “To Be Guardians of the Ethical Treatment of Patients,” describes the importance of the role of nurses and nursing faculty in achieving high standards of integrity to provide ethical care for our vulnerable patients. Moral reflection—critical analysis of one’s morals, beliefs, and actions—is a process through which a person develops and maintains moral integrity. Moral integrity in a professional setting is a goal in which one’s professional beliefs and actions are assessed and analyzed (reflected on) so that professional ethics continue to mature and respond to changes in practice (Hardingham, 2001). In any complex ethical situation, nurses should analyze their own actions so that they can reduce inner conflicts between their personal values and morals and their professional ethics. A model of nurses’ ethical reasoning developed by Dr. Roseanne Fairchild is featured in Box 5-2. When nurses are faced with ethical dilemmas but also encounter institutional constraints that limit their actions, they may experience moral distress (Pendry, 2007). Moral distress is the pain or anguish affecting the mind, body, or relationships in response to a situation in which the person is aware of a moral problem, acknowledges moral responsibility, and makes a moral judgment about the correct action; however, as a result of real or perceived constraints, the person participates in perceived moral wrongdoing (Nathaniel, 2002, p. 4). The following situation has several important ethical implications that cause a moral dilemma for the health care team and the family. Examine this scenario for various ethical issues, and think about what parts of this situation might pose a moral dilemma or moral distress for you. This example demonstrates numerous aspects of moral dilemmas and resulting moral distress. The nurse experienced moral distress, a sense of being unable to act in a way that he believes is moral in this situation. The nurse recognized the parents’ desire for their child to live; the possibility of pain and suffering of the infant; the real possibility of severe, long-term problems if she lives; the expense in terms of time and money; the emotional toll of care of the infant; and his own discomfort and sense of helplessness. This nurse also demonstrated that he was reflecting on his own practice and beliefs, which will help maintain his moral integrity. He will also use the lessons from this patient situation as he matures as a nurse, so that similar situations in the future may not be so distressful for him. Critical Thinking Challenge 5-1 refers to this patient situation; once you have studied the remainder of this chapter, you will have additional knowledge, tools, and perspective with which to consider the complexities of this scenario. To function effectively in today’s complex health care arena, nurses need to understand approaches to moral reasoning, theories of ethics, basic ethical principles, and ethical decision-making models. A significant advance in the professionalization of a traditional occupation such as nursing is the adoption of a formal code of ethics (Baker, 2009). Professional ethical codes such as that of the ANA provide substantial guidance in determining how to respond and act in practice settings when faced with an ethical dilemma. The remainder of this chapter will provide a basic orientation to these complex topics. Kohlberg (1976, 1986) proposed three levels of moral reasoning as a function of cognitive development: (1) preconventional, (2) conventional, and (3) postconventional. Each of these three levels is then considered in terms of stages. In the preconventional level, the individual is inattentive to the norms of society when responding to moral problems. Instead, the individual’s perspective is self-centered. At this level, what the individual wants or needs takes precedence over right or wrong. A person in stage 1 of the preconventional level responds to punishment. In stage 2, the person responds to the prospect of personal reward. Kohlberg observed the preconventional level of moral development in children younger than 9 years of age, as well as in some adolescents and adult criminal offenders. A more typical example, however, is that of a toddler for whom the word “no” has yet to have meaning as he or she persists in reaching for a breakable object on a table. The postconventional level consists of stage 5 and stage 6 and involves more independent modes of thinking than previous stages. The individual has developed the ability to define his or her own moral values. Individuals who apply moral reasoning at the postconventional level may ignore both self-interest and group norms in making moral choices. For example, they may sacrifice themselves on behalf of the group. Part of their moral reasoning and behavior is based on a socially agreed-on standard of human rights (Haynes, Boese, and Butcher, 2004). In this highest level of moral development, people create their own morality, which may differ from society’s norms. Kohlberg believed that only a minority of adults achieves this level. Progression through Kohlberg’s levels and their corresponding stages occurs over varying lengths of time for different individuals. The stages are sequential, they build on each other, and each stage is characterized by a higher capacity for moral reasoning than the preceding stage. Kohlberg (1976) suggested that certain conditions might stimulate higher levels of moral development. Intellectual development is one necessary characteristic. Individuals at higher levels intellectually generally operate at a higher stage of moral reasoning than those with lower levels of intellect. An environment that offers people opportunities for group participation, shared decision-making processes, and responsibility for the consequences of their actions also promotes higher levels of moral reasoning. Moral development is stimulated by the creation of conflict in settings in which the individual recognizes the limitations of present modes of thinking. For example, students have been stimulated to higher levels of moral reasoning through participating in courses on moral discussion and ethics (Kohlberg, 1973). Gilligan (1982) was concerned that Kohlberg did not adequately recognize women’s experiences in the development of moral reasoning. She noted that Kohlberg’s theories had largely been generated from research with men and boys, and when women were tested by using Kohlberg’s stages of moral reasoning, they scored lower than men. Gilligan believed that women’s and girls’ relational orientation to the world shaped their moral reasoning differently from that of men and boys. Women do not have inadequate moral development but different development because of their gender. Kohlberg’s inattention to gender differences meant that his theory was inadequate in explaining women’s moral development. Gilligan described a moral development perspective focused on care. In Gilligan’s view, the moral person is one who responds to need and demonstrates a consideration of care and responsibility in relationships. This perspective differed from the orientation toward justice described by Kohlberg (1973, 1976). In Gilligan’s research on moral reasoning, women most often exhibited a focus on care, whereas men more often exhibited a focus on justice. Gilligan described the differences between women and men’s moral reasoning not as a matter of better or worse, or mature or immature, but simply as a matter of having “a different voice” in moral reasoning. Gilligan (1982) suggested that women view moral dilemmas in terms of conflicting responsibilities. She described women’s development of moral reasoning as a sequence of three levels and two transitions, with each level representing a more complex understanding of the relationship between self and others. Each transition resulted in a critical reevaluation of the conflict between selfishness and responsibility. Gilligan’s levels of moral development are (1) orientation to individual survival; (2) a focus on goodness with recognition of self-sacrifice; and (3) the morality of caring and being responsible for others, as well as self. The focus of nursing on care as a moral attribute is congruent with Gilligan’s assertion that the dynamics of human relationships are “central to moral understanding, joining the heart and the eye in an ethic that ties the activity of thought to the activity of care” (p. 149). Critical thinking within a caring professional relationship is a sound basis for nursing practice. Nurses at times combine the care/justice perspective when forced to make ethical decisions. Nurses have shifted from the moral perspective of care to a justice orientation where universal rules and principles are used in moral decision making (Zickmund, 2004). Furthermore, as economics and scarcity of resources shape the delivery of health care, nurses may find themselves less able to use critical thinking, reflection, and higher stages of moral reasoning in their practice setting. The article described in this chapter’s Evidence-Based Practice Note demonstrates that this problem exists across nursing internationally. Those who subscribe to utilitarian ethics believe that “what makes an action right or wrong is its utility, with useful actions bringing about the greatest good for the greatest number of people” (Guido, 2006, p. 4). In other words, maximizing the greatest good for the benefit, happiness, or pleasure of the greatest number of people is moral. Utilitarianism assumes that it is possible to balance good and evil with a goal that most people experience good rather than evil. Professional health care providers use utilitarian theory in many situations. Consider, for example, the concept of triage, in which the sick or injured are classified by the severity of their condition to determine priority of treatment. Imagine that there is a plane crash in a remote area in which many of the survivors are severely burned. The local health care facility cannot manage all of the patients, and although air transport is available from a large medical facility 3 hours away, only those with the possibility of surviving can be transported. Those with less serious burns can be managed at a smaller hospital. This means that someone must make the decision as to who will and will not be treated. The most gravely injured will not be treated until those with a reasonable chance of survival are taken care of, although this means that some of the more severely injured will die awaiting care. As a function of utilitarianism, triage is accepted worldwide as an ethical basis for determining treatment. Virtue ethics was first noted in the works of Plato, Aristotle, and early Christians. According to Aristotle, virtues are tendencies to act, feel, and judge that develop through appropriate training but come from natural tendencies. This suggests that individuals’ actions are built from a degree of inborn moral virtue (Burkhardt and Nathaniel, 2002). More recently, bioethics literature has emphasized the character of the decision maker. Virtues refer to specific character traits, including truth telling, honesty, courage, kindness, respectfulness, compassion, fairness, and integrity, among others. These virtues become obvious through one’s actions and are expressions of specific ethical principles. Truthfulness, for example, embodies the principle of veracity, which will be discussed in the next section of this chapter. When virtuous people are faced with ethical dilemmas, they will instinctively choose to do the right thing because they have developed character through life experiences (Butts and Rich, 2005). The ability to respond to ethical dilemmas or situations in the health care arena is dependent on the nurse’s own integrity, honesty, courage, or other personal attributes. Practicing in an ethical manner requires a decision to act within the ethical code of the profession, demanding commitment, personal investment, and the intention and motivation to become a good nurse (Gallagher and Wainwright, 2005). Nurses’ ways of being and acting are essential to the integrity of nursing practice and patient care. Nurses frequently practice in challenging circumstances in which they must rely on their own integrity to ensure that care is given conscientiously and consistently. Virtues may be what separate the competent nurse from the exemplary nurse.

Ethics: Basic concepts for nursing practice

Basic definitions

Approaches to moral reasoning

Kohlberg’s stages of moral reasoning

Gilligan’s stages of moral reasoning

Ethical theories

Utilitarianism

Virtue ethics

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Ethics: Basic concepts for nursing practice

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access