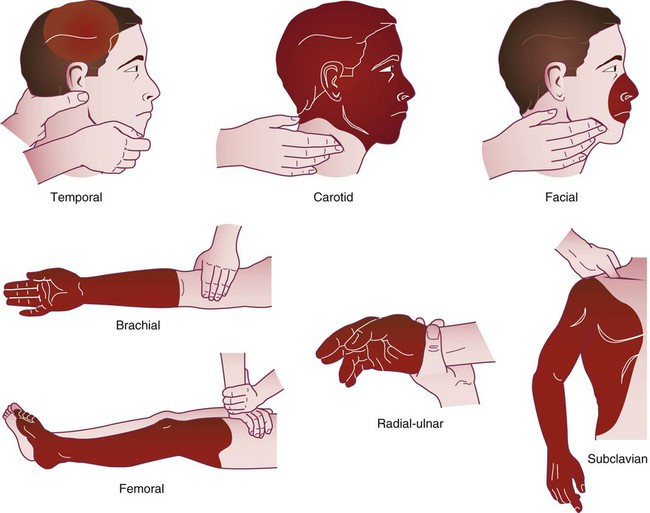

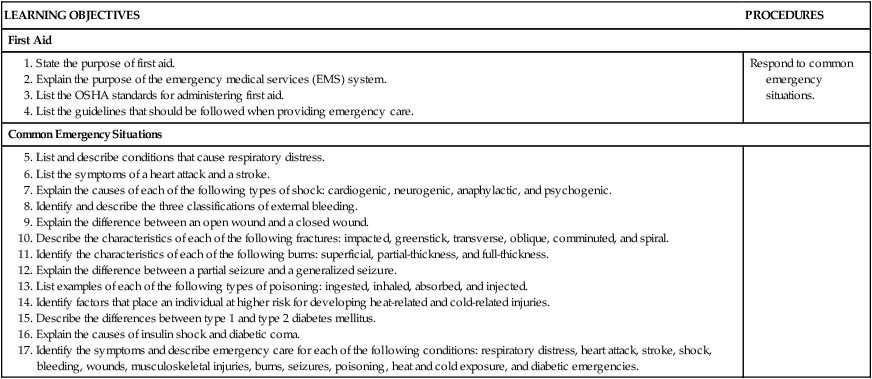

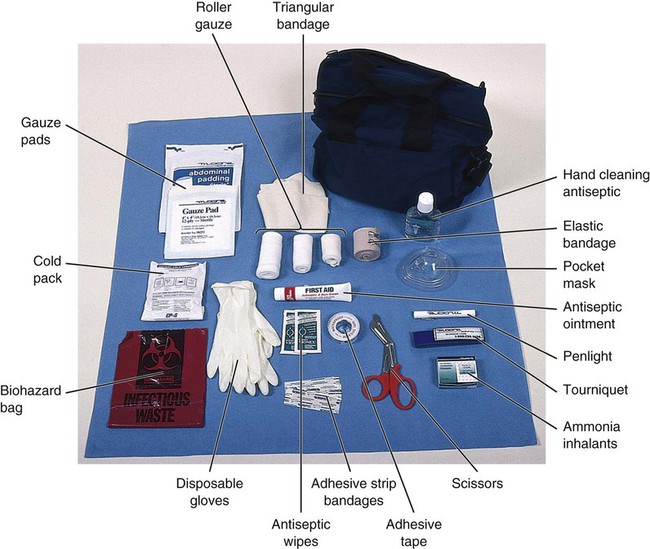

These guidelines should be followed when calling EMS: • Speak clearly and calmly to the EMD. Identify the problem as accurately and concisely as possible so that proper equipment and personnel can be sent. The EMD needs to know the number of victims, the condition of the victim or victims, and the emergency care that has already been administered. • The EMD will ask you for your phone number and address. In responding, relay to the dispatcher the exact location of the victim, including the correct street name and house number and (if applicable) the building name, floor, and room number. With the 911 enhanced emergency system, the address automatically appears on a monitor; however, there is a chance that the address will not show up on the monitor. In addition, the emergency may not be happening in the same location as the caller. If possible, have someone meet the ambulance personnel and direct them to the scene. • Do not hang up until the EMD gives you permission to do so. The dispatcher may need additional information or may give you instructions on treating the patient until EMTs arrive. The medical assistant should acquire and maintain a first aid kit. A first aid kit contains basic supplies to provide emergency care to individuals who have been injured or become suddenly ill (Figure 35-1). It is recommended that a first aid kit be kept at home and in the car. First aid kits are available at most drug stores. It also is possible to make your own. Along with the items shown in Figure 35-1, the first aid kit should include the phone numbers of the local emergency medical service, the poison control center, and the police and fire departments. It is important to check the first aid kit regularly and replace supplies as needed. To avoid exposure to bloodborne pathogens and other potentially infectious materials, the OSHA Bloodborne Pathogens Standard presented in Chapter 17 should be followed when performing first aid. The following guidelines help reduce or eliminate the risk of infection: 1. Make sure that your first aid kit contains personal protective equipment, such as gloves, a face shield and mask, and a pocket mask. 2. Wear gloves when it is reasonably anticipated that your hands will come into contact with the following: blood and other potentially infectious materials, mucous membranes, nonintact skin, and contaminated articles or surfaces. 3. Perform all first aid procedures involving blood or other potentially infectious materials in a manner that minimizes splashing, spraying, spattering, and generation of droplets of these substances. 4. Wear protective clothing and gloves to cover cuts or other lesions of the skin. 5. Sanitize your hands as soon as possible after removing gloves. 6. Avoid touching objects that may be contaminated with blood or other potentially infectious materials. 7. If your hands or other skin surfaces come in contact with blood or other potentially infectious materials, wash the area as soon as possible with soap and water. 8. If your mucous membranes (in eyes, nose, and mouth) come in contact with blood or other potentially infectious materials, flush them with water as soon as possible. 9. Avoid eating, drinking, and touching your mouth, eyes, and nose while providing emergency care or before you sanitize your hands. 10. If you are exposed to blood or other potentially infectious materials, report the incident as soon as possible to your physician so that postexposure procedures can be instituted. 1. Remain calm, and speak in a normal tone of voice. These measures help calm and reassure the patient. 2. Make sure that the scene is safe before approaching the patient. It is important that you protect yourself from harm in an emergency situation. 3. Before administering emergency care to a conscious patient, you must first have permission or consent. To obtain consent, you must inform the patient who you are, your level of training, and what you are going to do to help. Never administer care to a conscious patient who refuses it. When a life-threatening condition exists, and the patient is unconscious or otherwise unable to give consent, consent is assumed or implied. Under law, it is implied that if the patient could give consent to care, he or she would. 4. Follow the OSHA standards when providing emergency care to reduce or eliminate exposure to bloodborne pathogens or other potentially infectious materials. 5. Know how to activate your local EMS system. Activating the EMS is often the most important step you can take to help a patient who has experienced an injury or sudden illness. 6. Do not move the patient unnecessarily. Unnecessary movement can result in further injury or can be life-threatening to a patient with a serious condition. 7. Obtain information as to what happened from the patient, family members, co-workers, or bystanders. 8. Look for a medical alert tag on the patient’s wrist or neck. A medical alert tag provides information on a medical condition the patient may have. 9. Continue caring for the patient until more highly trained personnel arrive. On the arrival of emergency medical personnel or a physician, relay the condition in which you found the patient and the emergency care that has been administered. The emergency care for anaphylactic shock is the administration of epinephrine. Because time is a factor, individuals known to have a severe allergy carry an anaphylactic emergency treatment kit that contains injectable epinephrine (Figure 35-2) and oral antihistamines. With the kit, treatment for a severe allergic reaction can be started immediately. An individual who is about to faint should be placed in a position that facilitates blood flow to the brain and told to breathe deeply. The preferred position is to move the patient into a supine position with the legs elevated approximately 12 inches and the collar and clothing loosened (Figure 35-3). This position is not always possible, such as when a patient is seated; in this case, the patient’s head should be lowered between the legs (Figure 35-4). A patient who has fainted should be placed in the supine position with the legs elevated. It is recommended that a patient who has fainted should contact her or his physician for further evaluation. Emergency Care for External Bleeding If bleeding cannot be controlled with direct pressure, a pressure point can be used. A pressure point is a site on the body where an artery lies close to the surface of the skin and can be compressed against an underlying bone. Figure 35-5 illustrates pressure points. Using a pressure point helps slow or stop the flow of blood from the wound. The pressure points used most often are found on the brachial and femoral arteries. The brachial artery is located on the inside of the upper arm midway between the elbow and the shoulder. Squeezing the brachial artery helps control severe bleeding in the arm. The femoral artery is located in the groin, and squeezing helps control severe bleeding in the leg.

Emergency Medical Procedures

Introduction to Emergency Medical Procedures

Emergency Medical Services System

First Aid Kit

Osha Safety Precautions

Guidelines for Providing Emergency Care

Shock

Anaphylactic Shock

Psychogenic Shock

Bleeding

External Bleeding

Arterial Bleeding

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Emergency Medical Procedures

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access